Socio-Economic Development in Colonial District Multan (1849-1901)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Bulletin July.Pdf

July, 2014 - Volume: 2, Issue: 7 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: Polio spread feared over mass displacement 02 English News 2-7 Dengue: Mosquito larva still exists in Pindi 02 Lack of coordination hampering vaccination of NWA children 02 Polio Cases Recorded 8 Delayed security nods affect polio drives in city 02 Combating dengue: Fumigation carried out in rural areas 03 Health Profile: 9-11 U.A.E. polio campaign vaccinates 2.5 million children in 21 areas in Pakistan 03 District Multan Children suffer as Pakistan battles measles epidemic 03 Health dept starts registering IDPs to halt polio spread 04 CDA readies for dengue fever season 05 Maps 12,14,16 Ulema declare polio immunization Islamic 05 Polio virus detected in Quetta linked to Sukkur 05 Articles 13,15 Deaths from vaccine: Health minister suspends 17 officials for negligence 05 Polio vaccinators return to Bara, Pakistan, after five years 06 Urdu News 17-21 Sewage samples polio positive 06 Six children die at a private hospital 06 06 Health Directory 22-35 Another health scare: Two children infected with Rubella virus in Jalozai Camp Norwegian funding for polio eradication increased 07 MULTAN HEALTH FACILITIES ADULT HEALTH AND CARE - PUNJAB MAPS PATIENTS TREATED IN MULTAN DIVISION MULTAN HEALTH FACILITIES 71°26'40"E 71°27'30"E 71°28'20"E 71°29'10"E 71°30'0"E 71°30'50"E BUZDAR CLINIC TAYYABA BISMILLAH JILANI Rd CLINIC AMNA FAMILY il BLOOD CLINIC HOSPITAL Ja d M BANK R FATEH MEDICAL MEDICAL NISHTER DENTAL Legend l D DENTAL & ORAL SURGEON a & DENTAL STORE MEDICAL COLLEGE A RABBANI n COMMUNITY AND HOSPITAL a CLINIC R HOSPITALT C HEALTH GULZAR HOSPITAL u "' Basic Health Unit d g CENTER NAFEES MEDICARE AL MINHAJ FAMILY MULTAN BURN UNIT PSYCHIATRIC h UL QURAN la MATERNITY HOME CLINIC ZAFAR q op Blood Bank N BLOOD BANK r ishta NIAZ CLINIC R i r a Rd X-RAY SIYAL CLINIC d d d SHAHAB k a Saddiqia n R LABORATORY FAROOQ k ÷Ó o Children Hospital d DECENT NISHTAR a . -

The Spectrum of Beta-Thalassemia Mutations in Couples Referred for Chorionic Villus Sampling at Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur

Open Access Original Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.3265 The Spectrum of Beta-thalassemia Mutations in Couples Referred for Chorionic Villus Sampling at Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur Uffan Zafar 1 , Kamran Naseem 2 , Muhammad Usman Baig 3 , Zain Ali Khan 4 , Fariha Zafar 5 , Saba Akram 6 1. Radiology Department, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Quaid-E-Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur, PAK 2. Radiology Department, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Quaid-E-Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur , PAK 3. Medicine, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur, PAK 4. Gastroenterology, Pakistan Kidney and Liver Institute and Research Centre, Okara, PAK 5. Community Medicine, Quaid E Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur, PAK 6. Medical Ward, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Quaid-E-Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur, PAK Corresponding author: Uffan Zafar, [email protected] Abstract Introduction The prevalence of beta-thalassemia mutations is different in various castes, regions, and ethnic groups. By knowing this prevalence, we can conduct a targeted screening of only the high-risk population and only for the specific mutations that are prevalent in each group. Objective The purpose of this study was to determine the regional, caste-wise, and ethnic spectrum of beta- thalassemia mutations in couples referred for a prenatal diagnosis. Methods A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted at the thalassemia unit, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur, from October 1, 2015, to May 15, 2018. After obtaining informed consent, chorionic villus sampling (CVS) was performed in 144 women having a gestational age of 12 to 16 weeks. We took blood samples of the couples. A chromosomal analysis for 13 mutations was done at Punjab Thalassaemia Prevention Programme (PTPP), Lahore. -

Directorate General Health Services Punjab

0 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE GENERAL HEALTH SERVICES PUNJAB. D.G.H.S Office [DIRECTORATE GENERAL HEALTH SERVICES, PUNJAB] Sr. Code Name of Office Office No./Fax # No. DGHS, Punjab. 1. 042 99201139-40 (PSO) 99201139-40 ( P.A ) 2. 042 Fax 99201142 99238505 3. DHS (HQ) 042 99201141 DHS (EPI) 99201143 4. 042 99202812 Fax 99200405 ADG (Dengue) (EP&C) 99203235 042 5. Fax 99203235 DHS (P&D) 6. 042 99203793 7. DHS (MIS) 042 99205510 Program Manager( NCD) 8. 042 9. DHS (Dental). 042 99203751 Director (Pharmacy) 99201145 042 10. 99204622 DHS (CDC) 11. 042 99200970 DHS (TB). 35408894 12. 042 Fax 99203750 Director (Accounts). 13. 042 99202487 Additional Director (Admn). 99200987 14. 042 Fax 99201095 36118382 Res Additional Director (EPI) 15. 042 99200535 Additional Director (Malaria ) 16. 042 99202970 A. D (F&N/NCD) 99203749 042 17. Fax. 99204190 (Micronutrient) 99204014 18. 042 36290201 Fax Addl. Director (IRMNCH) 99205330-26 19. 042 99201098 Fax-9203394 1 Sr. Code Name of Office Office No./Fax # No. Addl. Director-I, IRMNCH 99200982 20. 042 99201098 Fax-9203394 P.M Hepatitis 21. 042 99204129 Addl. Director (MS&DC) 22. 042 99203505 Usman Ghani 23. 042 99200969 Additional Director (H.E). Media Manager 24. 042 99200969 Additional Director (TB-DOTS) 25. 042 99203750 Transport Manager, TMO 26. Workshop 042 35155845 27. (Supt.TPT) Budget & Accounts Officer 28. 042 99203487 Additional Director (Homeo) Shahid (Homeo Dr) 29. 042 99204191 Litigation Officer 30. Mr.Imran Ur Rehman 042 99200983 Computer Programer 31. 042 99200990 G.M (MSD) 35758336 32. 042 35873989 99201257 33. Bacteriologist 042 99200108 PD (HIV/AIDS). -

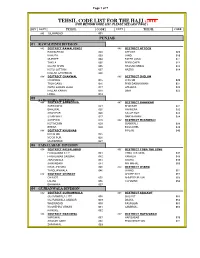

Tehsil Code List 2014

Page 1 of 7 TEHSIL CODE LIST FOR THE HAJJ -2016 (FOR MEHRAM CODE LIST, PLEASE SEE LAST PAGE ) DIV DISTT TEHSIL CODE DISTT TEHSIL CODE 001 ISLAMABAD 001 PUNJAB 01 RAWALPINDI DIVISION 002 DISTRICT RAWALPINDI 003 DISTRICT ATTOCK RAWALPINDI 002 ATTOCK 009 KAHUTA 003 JAND 010 MURREE 004 FATEH JANG 011 TAXILA 005 PINDI GHEB 012 GUJAR KHAN 006 HASSAN ABDAL 013 KOTLI SATTIAN 007 HAZRO 014 KALLAR SAYYEDAN 008 004 DISTRICT CHAKWAL 005 DISTRICT JHELUM CHAKWAL 015 JHELUM 020 TALA GANG 016 PIND DADAN KHAN 021 CHOA SAIDAN SHAH 017 SOHAWA 022 KALLAR KAHAR 018 DINA 023 LAWA 019 02 SARGODHA DIVISION 006 DISTRICT SARGODHA 007 DISTRICT BHAKKAR SARGODHA 024 BHAKKAR 031 BHALWAL 025 MANKERA 032 SHAH PUR 026 KALUR KOT 033 SILAN WALI 027 DARYA KHAN 034 SAHIEWAL 028 009 DISTRICT MIANWALI KOT MOMIN 029 MIANWALI 038 BHERA 030 ESSA KHEL 039 008 DISTRICT KHUSHAB PIPLAN 040 KHUSHAB 035 NOOR PUR 036 QUAIDABAD 037 03 FAISALABAD DIVISION 010 DISTRICT FAISALABAD 011 DISTRICT TOBA TEK SING FAISALABAD CITY 041 TOBA TEK SING 047 FAISALABAD SADDAR 042 KAMALIA 048 JARANWALA 043 GOJRA 049 SAMUNDARI 044 PIR MAHAL 050 CHAK JHUMRA 045 012 DISTRICT JHANG TANDLIANWALA 046 JHANG 051 013 DISTRICT CHINIOT SHORE KOT 052 CHINIOT 055 AHMEDPUR SIAL 053 LALIAN 056 18-HAZARI 054 BHAWANA 057 04 GUJRANWALA DIVISION 014 DISTRICT GUJRANWALA 015 DISTRICT SIALKOT GUJRANWALA CITY 058 SIALKOT 063 GUJRANWALA SADDAR 059 DASKA 064 WAZIRABAD 060 PASROOR 065 NOSHEHRA VIRKAN 061 SAMBRIAL 066 KAMOKE 062 016 DISTRICT NAROWAL 017 DISTRICT HAFIZABAD NAROWAL 067 HAFIZABAD 070 SHAKAR GARH 068 PINDI BHATTIAN -

Punjab Development Statistics 2017 Preface

Punjab Development Statistics 2017 Preface Bureau of Statistics has been issuing this publication since 1972. The present edition is the 43rd in the series. It provides important statistics in respect of social, economic and financial sectors of the economy at aggregate as well as sectoral levels. This publication contains data on almost all sectors of the Provincial economy with their break-up by Tehsil, District & Division as far as possible. Eight tables on Monthly Electricity and Gas Consumption, Number of Zoo, Number of Bulldozers, Small and Mini Dams, Recognized Slaughter Houses and two provisional tables on population census 2017 are also added in this issue. It includes some national data on important subjects like Major Crops, Foreign Trade, Labour Force & Employment, National Accounts, Population, Price and Transport etc. It contains a 'Statistical Abstract' which gives a comparative picture of information on almost all Socio- Economic sectors of Pakistan and the Punjab. Key findings of Multiple Indicator Cluster Servey (MICS): 2014 of some of the Socio-Economic Indicators are also included in this edition viz-a-viz Education, Health, Housing and Socio-Economic Development by district. Every effort has been made to include the latest available data in this publication. It is hoped that this publication will be useful to the policy makers, planners, researchers, govt. departments and other users of Socio-Economic data in public as well as private sector. I am thankful to various Provincial Departments / Agencies / Federal Ministries / Divisional/District offices for supplying the required data. Without their co-operation, it would have not been possible to release this publication in time. -

List of Licenced Trade Organizations Chambers of Commerce And

List of Licenced Trade Organizations Sr. No. Name of Trade Organization Address Phone Fax Email Website 2 3 4 5 6 14 Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry 1 The Federation of Pakistan Chamber of Commerce & Industry Federation House, Main Clifton, Shahrah-e-Firdousi, Karachi, 021-35873691, 93,94 021-5874332 [email protected] http://fpcci.org.pk/ PO Box. 13875 Chambers of Commerce and Industry 1 Faisalabad Chamber of Commerce & Industry FCCI-Complex, Aiwan-e-Sanat-Tijarat Road, Canal Park, East 041-8520823-5, 041-9230270 [email protected] http://www.fcci.com.pk/ Canal Road, Faisalabad 9230265-67 2 Gujrat Chamber of Commerce & Industry Chamber Building, P.O Box 169, G.T.Road (opp: National 0533706113-15 0533706112 [email protected], www.gtcci.org.pk Frunishers) Gujrat [email protected] 3 Hyderabad Chamber of Commerce & Industry 41/488, Behind G.P.O. Saddar, Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road 022-2784972-5 022-2784977 [email protected] http://www.hydcci.com/ Hyderabad P.O Box # 99 4 Islamabad Chamber of Commerce & Industry Aiwan-e-Sanat-O- Tijarat Road, Sector G-8/1, Mauve Area 051-2250526 ; 051-2252950 [email protected], http://www.icci.com. Islamabad 2253145 [email protected] pk/ 5 Karachi Chamber of Commerce & Industry Awan-e-Tijrat Road off Shahrah-e-Liaqat.P.O.Box. 4158 021-99218001-9 021-99218010 [email protected], http://kcci.com.pk/ Karachi 74000 [email protected] 6 Lahore Chamber of Commerce & Industry 11-Shahra-e-Aiwan-e-Tijarat, Lahore. P.O.Box 597 111-222-499 ; 042- 042-6368854 [email protected] http://www.lcci.co 6305538-40 m.pk/ 7 Chamber of Commerce & Industry, Quetta (Balochistan) Chamber Building Zarghoon Road, P.O. -

Village List of Multan Division , Pakistan

Cel'.Us 51·No. 30B (I) M.lnt.6-19 300 CENSUS OF PAKISTAN, 1951 VILLAGE LIST PUNJAB Multan Division OFFICE Of THE PROVINCIAL · .. ·l),ITENDENT CENSUS, J~ 1952 ,~ :{< 'AND BAHAWALPUR, P,IC1!iR.. 10 , , FOREWOf~D This Village Ust has been prepared from the material collected in con nection with the Census of Pakistan, 1951. The object of the List is to present useful information about our villages. It was considered that in a predominantly rural country like Pakistan, reliable village statistics should be available and it is hoped that the Village List will form the basis for the continued collection of such statistics. A summary table of the totals for each tehsil showinz its area to the nearest square mile, and its population and the number of houses to the nearest hundred is given on page I together with the page number on which each tehsil begins. The general village table, which has been compiled district-wise and arranged tehsil-wise, appears on page 3 et seq. Within each tehsll th~ Revenue Kanungo ho/qas are shown according to their order in the census records. The Village in which the Revenue Kanungo usually resides is printed in bold type at the beginning of each Kanungo halqa and the remaining villages comprising the halqas, are shown thereunder in the order of their revenue hadbast numbers, which are given in column a. Rakhs (tree plantations) and other similar area,. even where they are allotted separate revenue hadbast nurY'lbcrs have not been shown as they were not reported in the Charge and Household summaries, to be inhabited. -

Punjab Aab-E-Pak Authority

GOVERNMENT OF PUNJAB PUNJAB AAB-E-PAK AUTHORITY VOLUME-II TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR SUPPLY CONSTRUCTION, INSTALLATION OF WATER FILTRATION PLANTS IN BAHAWALPUR & MULTAN DIVISION JUNE 2021 PUNJAB AAB-E-PROJECT (PAPA) SUPPLY CONSTRUCTION, INSTALLATION OF WATER FILTRATION PLANTS IN BAHAWALPUR & MULTAN CONTRACT DOCUMENTS DIVISION TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR SUPPLY CONSTRUCTION, INSTALLATION OF WATER FILTRATION PLANTS IN BAHAWALPUR & MULTAN DIVISION, PUNJAB Contents 1 GENERAL PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 DESCRIPTION OF WORK .................................................................................................................................................. 2 1.4 CONTRACT AREA ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 1.5 PROJECT DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 GENERAL REQUIREMENTS -

S.R.O. No.---/2011.In Exercise Of

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 9, 2021 39 S.R.O. No.-----------/2011.In exercise of powers conferred under sub-section (3) of Section 4 of the PEMRA Ordinance 2002 (Xlll of 2002), the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority is pleased to make and promulgate the following service regulations for appointment, promotion, termination and other terms and conditions of employment of its staff, experts, consultants, advisors etc. ISLAMABAD SATURDAY, JANUARY 9, 2021 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY AND RESEARCH NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 6th January, 2021 S. R. O. (17) (I)/2021.—In exercise of the powers conferred by section 15 of the Agricultural Pesticides Ordinance, 1971 (II of 1971), and in supersession of its Notifications No. S.R.O. 947(I)/2002, dated the 23rd December, 2002, S.R.O. 1251 (I)2005, dated the 15th December, 2005, S.R.O. 697(I)/2005, dated the 28th June, 2006, S.R.O. 604(I)/2007, dated the 12th June, 2007, S.R.O. 84(I)/2008, dated the 21st January, 2008, S.R.O. 02(I)/2009, dated the 1st January, 2009, S.R.O. 125(I)/2010, dated the 1st March, 2010 and S.R.O. 1096(I), dated the 2nd November, 2010. The Federal Government is pleased to appoint the following officers specified in column (2) of the Table below of Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab, to be inspectors within the local limits specified against each in column (3) of the said Table, namely:— (39) Price: Rs. -

Immunization Supply Chain Improvement Roadmap for Pakistan

Immunization Supply Chain Improvement Roadmap for Pakistan TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Background and Project Overview ................................................................................................................ 8 High-Level Recommendations For Pakistan to Move to a Next-Generation Immunization Supply Chain ... 15 Streamlined and Efficient supply chain, not based on administrative levels ........................................... 15 Equity Lens for Supply Chain Improvement ............................................................................................. 16 Professional Logistics Workforce, Saving Staff Time for Service Delivery ................................................ 16 Clear Data Visibility .................................................................................................................................. 17 Leadership Using Data for Management and Decision-Making ............................................................... 17 Modelling Results, Recommendations and Next Steps .............................................................................. -

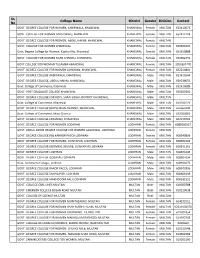

Multan 652410673

Sr. College Name District Gender Division Contact No GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, KABIRWALA, KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Female MULTAN 652410673 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN SARAI SIDHU, KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Female MULTAN 652412228 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, ABDUL HAKIM, KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Female MULTAN GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Female MULTAN 659200107 Govt. Degree College for Women, Katcha Kho, Khanewal KHANEWAL Female MULTAN 652610888 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN MIAN CHANNU, KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Female MULTAN 652662293 GOVT.COLLEGE FOR WOMAN TULAMBA KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Female MULTAN 3059367470 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN JAHANIAN, KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Female MULTAN 652210801 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE KABIRWALA, KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Male MULTAN 652410544 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE, ABDUL HAKIM, KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Male MULTAN 659239055 Govt. College of Commerce, Kabirwala KHANEWAL Male MULTAN 652410689 GOVT. POST GRADUATE COLLEGE KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Male MULTAN 659200350 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR BOYS, SARAI SIDHU, DISTRICT KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Male MULTAN Govt. College of Commerce, Khanewal KHANEWAL Male MULTAN 659200129 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE (BOYS) MIAN CHANNU, KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Male MULTAN 652660238 Govt. College of Commerce, Mian Channu KHANEWAL Male MULTAN 652020081 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE JAHANIAN, KHANEWAL KHANEWAL Male MULTAN 652210701 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN LODHRAN LODHRAN Female MULTAN 6089200137 GOVT. ABDUL KARIM DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN GALAYWAL, LODHRAN LODHRAN Female MULTAN GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE (W) KAHROR PACCA LODHRAN LODHRAN Female MULTAN 608340836 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, DUNYAPUR, LODHRAN LODHRAN Female MULTAN 608304794 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE (WOMEN) 365/WB, DUNYAPUR LODHRAN LODHRAN Female MULTAN 608531261 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE LODHRAN LODHRAN Male MULTAN 608921046 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE GOGRAN, LODHRAN LODHRAN Male MULTAN 608607094 Govt. Commerce College , Lodhran LODHRAN Male MULTAN 608921072 GOVT. -

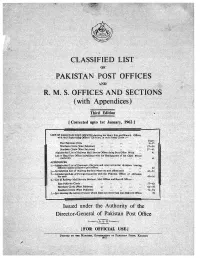

Pak Pos and RMS Offices 3Rd Ed 1962

Instructions for Sorting Clerks and Sorters ARTICLES ADDRl!SSBD TO TWO PosT-TOWNS.-If the address Dead Letter Offices receiving articles of the description re 01(an article contains the names of two post-town, the article ferred in this clause shall be guided by these instructions so far should, as a general rule, be forwarded to whichever of the two as the circumstances of each case admit of their application. towns is named last unless the last post-town- Officers employed in Dead Letter Offices are selected for their special fitness for the work and are expected to exercise intelli ( a) is obviously meant to indicate the district, in which gence and discretion in the disposal of articles received by case the article should be . forwar ~ ed ~ · :, the first them. named post-town, e. g.- A. K. Malik, Nowshera, Pes!iaivar. 3. ARTICLES ADDRESSED TO A TERRITORIAL DIVISION WITH (b) is intended merely as a guide to the locality, in which OUT THE ADDITION OF A PosT-TOWN.-If an article is addressed case the article should be forwarded to the first to one of the provinces, districts, or other territorial divisions named post-town, e. g.- mentioned in Appendix I and the address does not contain the name of any post-town, it should be forwarded to the post-town A. U. Khan, Khanpur, Bahawalpur. mentioned opposite, with the exception of articles addressed to (c) Case in which the first-named post-town forms a a military command which are to be sent to its headquarters. component part of the addressee's designation come under the general rule, e.