Philosophical Discussions of Moral Concerns in a 7Th Grade Language Arts Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

EPW Matches EPIC/QHD: “The Finisher” Racer Mckay (1,524-216-54) *17 $2,454,800 … #160 Or 501

#32 Mega Empire Champion * wins 10 free EPW matches EPIC/QHD: “The Finisher” Racer McKay (1,524-216-54) *17 $2,454,800 … #160 or 501 Heritage Champion * wins 5 free EPW matches EPIC/QHD: “The Uprising” Dagger Wolfkill (1,222-156-28) *17 $1,857,600 … #158 or 502 Chaotic Champion ORDER: Hazrat (407-100-15) *20 $682,200 … #72 or 503 Primacy Champion EPIC/YmY: Hot Toddy (487-122-28) *7 $974,500 … #128 or 504 No Mercy Champion ORDER: Sicko the Clown (276-81-21) *14 $500,400 … #81 or 505 Noble Champion EDGE: Apostle (5-7-1) *2 $66,400 … #135 or 506 Anarchy Rising Champion EPIC/QHD: “Showtime” Tommy Christopher September 2021 (1,781-313-74) *19 $2,921,100 … #48 or 507 Shining Knight Champion EPIC/3HDR: “King of Riches” Shota Tokido (1,212-207-51) *15 $1,961,600 … #159 or 508 Explicit Champion EPIC/YmY: Whiskey Sour (237-89-14) *4 $558,300 … #75 or 509 Eminence Champion Johnny Moore Fiend (723-166-31) *19 $1,275,200 … #70 or 510 Despair Champion * from the battle royal EPIC/3HDR: “Suicidal Nightmare” Darby Christopher (1,428-273-64) *17 $2,480,600 … #50 or 511 Regal Champion Xander Wolfe (212-85-15) *6 $532,800 … #78 or 512 Total Annihilation Champions VIRUS: “Spotlight” Carlos Spickelmier and “King of Monsters” Wesley Spickelmier #56 & #77 or 789 Crossfire Champions EDGE: Joe Bloggs and John Doe #59 & #61 or 987 Dastardly Deeds Champions * win another 5 free matches LPPF: Slaughterdog Kreo, Slaughterdog Cujo, and Slaughterdog Rex #132, #133, & #134 or 789 Pure Blood Champions EPIC/YmY: Whiskey Sour, EPIC/AoS: Jerrad Syn, and Vicious Valentine #75, #129, & #157 or 987 Battle Royal Winner * wins 19 free EPW matches EPIC/YmY: Hot Toddy (487-122-28) *7 $974,500 … #128 1. -

Tommy Rock's Life Story

Tommy Rock’s Life Story The Many Lives of Roeck-n-Roll Tommy started his quest at age 2 doing the twist to his half sister Linda's Beatles and Chubby Checker records. At 5 he began singing along with his parents' Johnny Mathis, Frank Sinatra, and Nat King Cole records. Encouraged by his Mother, he accurately mimicked the popular songs of the era, and began playing guitar at age 8. Tutored by his older half brother Bobby, he learned very quickly, and began rivaling his mentor's skills within a few years. With his Sears cassette recorder and his Silver tone guitar and amp in case always in hand he would practice singing and playing for endless hours, until his parents made him go to bed. While in grammar school, he excelled in the arts. Drawing, painting, creative writing, singing in choir, playing clarinet and saxophone at school functions, he won many awards. At age 15 he began pursuing the guitar with a mad passion. He was influenced at first by John Denver, Jim Croce, and Elton John and then later by bands like Aerosmith, The Who, Led Zeppelin, Rush, and The Stones. With the warm tube tones, and screaming vocals of the 70's at hand, he was star stricken and vowed that music would be his life. His younger brother David was also a gifted student, and made good grades, especially in metal shop and auto-mechanics. In 1977 His Father Robert Roeck, a Veteran of WW2, hailing from Chicago, and a Journeyman Maintenance Machinist of 30 years, with Bethlehem Steel Corporation, retired and moved his family to the resort community of Hot Springs, Arkansas. -

Creep Show Licensed Psychologist with Of- Fices in the Tall Pine Center in Somerset

Inside: Time Off's Restaurant Guide Franklin News-Record Vol. 36, No. 12 Thursday, March 21, 1991 50 0 NEWS Chemical cloud still has officials perplexed By Laurie Lynn Strasser over how its source —• a leaky been in business two years, needs no because it's too dangerous," said said, because a deposit upon purchase Staff Writer container of hydrogen chloride — DEP operating permit because it is Somerset Recycling's owner, Bud usually serves as incentive for BRIEFS wound up at Somerset Recycling, not a full-scale recycling facility, Mr. Flynn. "We didn't find the tanks empties to be returned to the com- State officials have yet to de- located at 921 Route 27, in the first Staples said, adding that the only until Saturday when we were clean- pany that distributes them. termine who is accountable for a place. laws pertaining to a situation such as ing a pile of steel to ship out to a If the company that made them caustic chemical cloud that exuded Hydrogen chloride gas reacts with this come "after the fact." shredder in Newark." were still in business, Mr. Flynn said. from a Franklin junkyard, hovered Spring rec moisture, cither in the atmosphere or "Our emergency response people Purchasing metal by the truckload it would be responsible for disposal. over town and wafted into New in living organisms, to form have referred the matter to the can be like buying strawberries in the But in this case, he speculated, what- Brunswick for seven hours Saturday. Franklin Township's Depart- hydrochloric acid, which can irritate Division of Environmental Quality to supermarket, Mr. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Tommy Laster - Poems

Poetry Series Tommy Laster - poems - Publication Date: 2014 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Tommy Laster(Feb 7 1988) A Poets Knowledge is too strive to be the best no matter who he or she is, what I love about poetry is you can express your mind fiction and no fiction, you can take your English Version and translate them to Spanish or any other country language by using Google translate, Poetry is a act of everyday life actions taking into account by Placing them on paper, for me poetry is a way to escape everyday life things and interact with everyday people, I'm bipolar and Recieve a check but it doesn't counter act my doing of poetry because I make no money at it so I do poetry for free to express my true feelings about this world and this life we live in. My Personal History (Well) : Born on February 7,1988 COOK MIDDLE SCHOOL Moved to Adel, Georgia Started School at CHS (COOK COUNTY HIGH) Left CHS (COOK COUNTY HIGH) Moved to Albany, Georgia Moved to Lakeland, Georgia First First Christmas Card Certificate Of Completion Moved to Lakeland Ga. Pre-Court Trial/Court Trial Notice New Beginning Church Letter Eber & Wein Publishing Moved to Adel, Georgia Toy Story 3 (Movie) Moved to Adel, Georgia Overcame Chest Pain First Valentines Day Card Mark Zirkle (Tire Changer & Wood Buster) Council Meeting LOOKIN' FOR AUDIO TAPES First met Gregory Lamar Paige Harveys (Food Shoping) First Vote 4th Of July City Of Adel Council Meeting (Preliminary Agenda) www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 CHS (COOK COUNTY HIGH) 2005 to 2007 Mr. -

November 22, 1963

Volume XXIII No. 12 Hometown Newspaper for Glen Cove, Sea Cliff, Glen Head, Glenwood, Locust Valley and Brookville Week of 11/21/13 75C November 22, 1963 It’s Official- Glen Cove’s New Mayor Is Reginald Spinello For those of us of a certain age, November 22nd comes to us each year pretty much the same way the phrase 9-11 has lately. Each of us knows where we were on the fateful day and what we were doing when we found out what It’s official, Glen Cove has had happened. a new Mayor. The final count of Fifty years ago in November, Americans were just getting used to the absentee ballots have been count- presidency of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Our young president had been through ed electing Republican Reginald an eventful first three years, hardened by a near-nuclear confrontation with the Spinello over incumbent Ralph Soviet Union over missile placements in Cuba. In matters of race, our nation V. Suozzi by 74 votes. was coming to grips with an issue still not resolved. John F. Kennedy guided us Spinello received a total through these troubled waters with what most of us felt at the time to be a very 3,433 votes to Suozzi’s 3,359, skillful leadership. In mid-November of 1963, Mr. Kennedy seemed poised to according to the Nassau County launch a bid for a second term, riding a wave of personal popularity. Board of Elections. To be sure, the Cold War, civil rights, Vietnam and national economy were Had Suozzi won this would all challenges that our young chief executive faced moving forward. -

Tommy Wilhelm's Psychological Rebirth in Saul

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 4, Series. 6 (April. 2020) 05-10 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Tommy Wilhelm’s Psychological Rebirth in Saul Bellow’s Seize the Day: a Study from Jungian Perspective Kamol Karmakar Lecturer, Department of English, University of Science and Technology Chittagong (USTC) Zakir Hossain Road, Foy’s Lake, Khulshi, Chattogram 4202 Abstract: This paper attempts to investigate how Tommy Wilhelm, the protagonist of Saul Bellow‟s masterpiece Seize the Day (1956), had a psychological rebirth in the middle of a totally disorganized and confused life. Here, the term „rebirth‟ does not mean Tommy had this immortality mantra, the mantra for rejuvenating himself from any kind of disease or any kind of wound or injury, but is metaphorically used to express the self-actualization which is very surprisingly created in his mind. This paper tries to reach its goal by using the lens of Jungian point of view, showing how Tommy ultimately realizes that striving after perfection is like chasing after wind. Many researchers showed that Tommy, having a truckload of troubles, could not literally learn anything from his numerous mistakes. But, the result of this research disagrees with the previous researchers showing that, despite being surrounded by too many money-oriented people in a money-adoring society, and having done so many mistakes in his life, Tommy learned a whole lot of things, and ultimately realized how he should utilize his time to live his life. Needless to say, he had a shift of his mindset to a whole new level, and that is, going from the state of being so pessimistic to optimistic. -

Caring for Children Who Have Experience Trauma

Illustrations by Erich Ippen, Jr. Used with permission. Module 7: Becoming an Advocate Resource Parent Workshop: Participant Handbook 7-1 February 2010 7-2 The National Child Traumatic Stress Network www.nctsn.org Learning Objectives After completing this module, you should be able to: n List at least three of the basic elements of trauma-informed advocacy. n List at least four indicators that a child may need the support of trauma-informed therapy. n Describe specific actions you can take with an actual member of your child’s team. Resource Parent Workshop: Participant Handbook 7-3 February 2010 7-4 The National Child Traumatic Stress Network www.nctsn.org Module 7: Becoming an Advocate Illustrations by Erich Ippen, Jr. Used with permission. 1 Essential Elements 7 and 8 7. Be an advocate for your child. 8. Promote and support trauma-focused assessment and treatment for your child. 2 Know Your Child’s Team (Group Activity) Caseworker Legal Resource team parents Educators Therapist Medical Child team Birth parents Other birth family members Strong, positive connection Weak connection Stressful connection 3 Resource Parent Workshop: Participant Handbook 7-5 February 2010 Working as a Team The team members involved in your child’s life: Share a commitment to your child’s safety, permanency, and well-being Have distinct roles and responsibilities Relate to your child in different ways Are NOT equally trauma-informed 4 I would feel like I was just being passed around and not really knowing what was going on. No one explained anything to me. I didn’t even know what rights I had . -

The Bazaar of Bad Dreams Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE BAZAAR OF BAD DREAMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stephen King | 496 pages | 30 Nov 2015 | Hodder & Stoughton General Division | 9781473698888 | English | London, United Kingdom The Bazaar of Bad Dreams PDF Book Definitely a story to be forgotten soon. I'm not even a big baseball fan and this one was one of my favorites in the book. After discovering his talent- he swears to use it sparingly and on bad people only, but this has unforeseen consequences. Since his first collection, Nightshift , published 35 years ago, Stephen King has dazzled listeners with his genius as a writer of short fiction. Not his usual. There are thrilling connections between stories, including themes of morality, the afterlife, guilt, and what we would do differently if we could see into the future or correct the mistakes of the past. A series of mile drives in college led to Mile 81 and the most homicidal car since Christine. I was delighted to see Drunken Fireworks included as it was originally released as an audiobook exclusive this summer. Plus, it features autobiographical comments on when, why and how he came to write or rewrite each story. More Details It's cool. Pain you cannot see is usually written off or flat out ignored by the very people who you seek help from. Add to Wish List failed. Although I must say, I really love the structure of this story. Cancel anytime. There were some stories here I loved , and some that, as some of Mr. Listeners also enjoyed Mile 81 — This story was surprisingly and glaringly amateur. -

![Journal of the Short Story in English, 52 | Spring 2009, « General Issue » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Juin 2011, Consulté Le 03 Décembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7873/journal-of-the-short-story-in-english-52-spring-2009-%C2%AB-general-issue-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-juin-2011-consult%C3%A9-le-03-d%C3%A9cembre-2020-4897873.webp)

Journal of the Short Story in English, 52 | Spring 2009, « General Issue » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Juin 2011, Consulté Le 03 Décembre 2020

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 52 | Spring 2009 General issue Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/935 ISSN : 1969-6108 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Rennes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 juin 2009 ISSN : 0294-04442 Référence électronique Journal of the Short Story in English, 52 | Spring 2009, « General issue » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 juin 2011, consulté le 03 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/935 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 3 décembre 2020. © All rights reserved 1 SOMMAIRE Foreword Linda Collinge-Germain et Emmanuel Vernadakis Dangerous Similitude in Charles Dickens’ “To Be Read at Dusk” Kimberley Jackson A History of the American Mind: "Young Goodman Brown" Steven Olson 'The Half Shall Remain Untold': Hunilla of Melville's Encantadas K. M. Wheeler Linguistic Structure and Rhetorical Resolution in Katherine Mansfield "The Garden Party" Stephen E. Severn La tentation mélancolique dans One Warm Saturday de Dylan Thomas Claude Maisonnat Identity is a Slippery Fish – the Discovery of Identity in Elizabeth Bowen's Short Story "The Demon Lover" Zuzanna Zarebska Sanches Cultural In-Betweenness in "L'expulsé"/"The Expelled" by Samuel Beckett Linda Collinge-Germain Index Nominorum, Issues 41-51 Index Nominum personarum, Issues 41-51 “Echo's Bones": Samuel Beckett's Lost Story of Afterlife José Francisco Fernández Samuel Beckett's maternal passion or hysteria at work in company/compagnie Pascale Sardin Raymond Carver's "Myers trio" Robert Miltner Saroyan's lonely fruitcakes, and other goofs: strategies of resistance to the culture of abundance Mauricio D. -

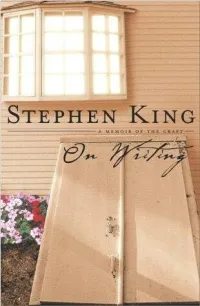

On Writing : a Memoir of the Craft / by Stephen King

l l SCRIBNER 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Stephen King All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work. DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING Set in Garamond No. 3 Library of Congress Publication data is available King, Stephen, 1947– On writing : a memoir of the craft / by Stephen King. p. cm. 1. King, Stephen, 1947– 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 3. King, Stephen, 1947—Authorship. 4. Horror tales—Authorship. 5. Authorship. I. Title. PS3561.I483 Z475 2000 813'.54—dc21 00-030105 [B] ISBN 0-7432-1153-7 Author’s Note Unless otherwise attributed, all prose examples, both good and evil, were composed by the author. Permissions There Is a Mountain words and music by Donovan Leitch. Copyright © 1967 by Donovan (Music) Ltd. Administered by Peer International Corporation. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Granpa Was a Carpenter by John Prine © Walden Music, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. Honesty’s the best policy. —Miguel de Cervantes Liars prosper. —Anonymous First Foreword In the early nineties (it might have been 1992, but it’s hard to remember when you’re having a good time) I joined a rock- and-roll band composed mostly of writers.