WG and Anthony Boucher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick

EUGÊNIA BARTHELMESS Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- Graduação em Letras, Área de Concentra- ção Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, do Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federai do Paraná, como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre. Orientadora: Prof.3 Dr.a BRUNILDA REICHMAN LEMOS CURITIBA 19 8 7 OF PHILIP K. DICK ERRATA FOR READ p -;2011 '6:€h|j'column iinesllll^^is'iiearly jfifties (e'jarly i fx|fties') fifties); Jl ' 1 p,.2Ò 6th' column line 16 space race space race (late fifties) p . 33 line 13 1889 1899 i -,;r „ i i ii 31 p .38 line 4 reel."31 reel • p.41 line 21 ninteenth nineteenth p .6 4 line 6 acien ce science p .6 9 line 6 tear tears p. 70 line 21 ' miliion million p .72 line 5 innocence experience p.93 line 24 ROBINSON Robinson p. 9 3 line 26 Robinson ROBINSON! :; 1 i ;.!'M l1 ! ! t i " i î : '1 I fi ' ! • 1 p .9 3 line 27 as deliberate as a deliberate jf ! •! : ji ' i' ! p .96 lin;e , 5! . 1 from form ! ! 1' ' p. 96 line 8 male dis tory maledictory I p .115 line 27 cookedly crookedly / f1 • ' ' p.151 line 32 why this is ' why is this I 1; - . p.151 line 33 Because it'll Because (....) it'll p.189 line 15 mourmtain mountain 1 | p .225 line 13 crete create p.232 line 27 Massachusetts, 1960. Massachusetts, M. I. T. -

Book Reviews from the Sf Press

BOOK REVIEWS FROM THE SF PRESS Solar Lottery Anthony Boucher: Fantasy & Science Fiction August 1955, p. 94 Philip K. Dick’s SOLAR LOTTERY (Ace, 35 cents) is kept from a Grade A rating only by a tendency, in both its nicely contrasted plots, to dwindle away at the end. This first novel by one of the most interesting new magazine writers (one of F&SF’s discoveries, I may add proudly) creates a strange and highly convincing and self-consistent future society, peculiarly governed by Games Theory and the principle of randomness; against this background, built up with the detail of a Heinlein and the satire of a Kornbluth, it relates a taunt melodrama of political conflict and a stirring space-quest to rediscover a lost tenth planet. P. Schuyler Miller: Astounding Science Fiction November 1955, p. 151 Here’s another demonstration that you get a whale of a lot for your money from Ace. “Solar Lottery” is in the van Vogt tradition, taking a man with a mission, involving him hopelessly in a society built on a novel concept of science or philosophy, and allowing all sorts of unseen forces to prowl and putter behind the scenes. This time the gimmick is not non-Aristotelian semantics but von Neumann’s Theory of Games, which the author has built up as the mainspring of a Twenty-third Century planetary lottery whose one winner, the Quizmaster, is dictator of mankind until an assassin cuts him down or the “bottle” – never quite explained – twitches someone else in his place. Outside the Game, those who have special skills useful to the manufacturing combines may sell themselves into absolute serfdom, while those who have only manual skills are “unclassified” and hopeless. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

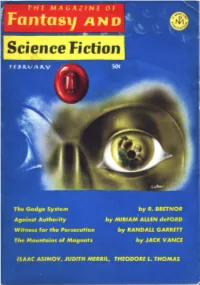

This Month's Issue

FEBRUARY Including Venture Science Fiction NOVELETS Against Authority MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD 20 Witness for the Persecution RANDALL GARRETT 55 The Mountains of Magnatz JACK VANCE 102 SHORT STORIES The Gadge System R. BRETNOR 5 An Afternoon In May RICHARD WINKLER 48 The New Men JOANNA RUSS 75 The Way Back D. K. FINDLAY 83 Girls Will Be Girls DORIS PITKIN BUCK 124 FEATURES Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 19 Books JUDITH MERRIL 41 Desynchronosis THEODORE L. THOMAS 73 Science: Up and Down the Earth ISAAC ASIMOV 91 Editorial 4 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by George Salter (illustrating "The Gadge System") Joseph W. Ferman, PUBLISHER Ed~mrd L. Fcrma11, EDITOR Ted White, ASSISTANT EDITOR Isaac Asimov, SCIENCE EDITOR Judith Merril, BOOK EDITOR Robert P. llfil/s, CONSULTING EDITOR The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Volnme 30, No. 2, Wlrolc No. 177, Feb. 1966. Plfblished monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 50¢ a copy. Aunual subscription $5.00; $5.50 in Canada and the Pan American Union, $6.00 in all other cormtries. Publication office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N.H. 03302. Editorial and ge11eral mail sholfld be sent to 3/7 East 53rd St., New York, N. Y. 10022. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N.H. Printed in U.S.A. © 1965 by Mercury Press, Inc. All riglrts inc/fl.ding translations iuto ot/rer la~>guages, resen•cd. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed ent•ciBPes; tire Publisher assumes no responsibility for retlfm of uusolicitcd ma1111scripts. BDITOBIAL The largest volume of mail which crosses our desk each day is that which is classified in the trade as "the slush pile." This blunt term is usually used in preference to the one y11u'll find at the very bottom of our contents page, where it says, ". -

Fanscient 12

fflnsciEriT• No. 12 SUMMER, 1950 | Three years and 400 pages ago, we brought out the first issue of The FANSCIEOT. This issue completes the third year, and just under the wire too, as it’s nearly three months late. For this 1 decline to Volume 4, Whole Number 12 apologize as only one who was idiot enough to accept the chairmanship of a world stf-con would be putting out an issue even'now. Those few Number 2. tfefflnsciEnj SUMMER, 1950 who have been the chairmen or work-horses of past cons will know what I mean---- the rest of you will just have to imagine as best you can. Even now, there would be no issue save for the valiant efforts of CONTENTS of the SUMMER 1950 Issue Miles Eaton, who with his wife, Betty, prepared much of the copy for publication and Jim Bradley, who nobly assisted in the final preparation of the issue. Incidentally, Jim’s fanzine, DESTINY, is going lithoed COVER Photo from DESTINATION MOON with its second issue, ready now. 16 lithoed Fanscient-sized pages for 150. Order from Jim Bradley, 545 NE San Rafael St., Portland 12, Ore. UNBELIEVITUDINOSITY JOHN & DOROTHY DE COURCY 4 Illustrated by J. M. Higbee After reading Anthony Boucher’s autobiography in the AUTHOR, AUTHOR department, I’m sure you’ll be ready to come up to the NORWESCON where OUT OF LEGEND: The Babd Catha Text dt Picture by MILES EATON 8 Tony will be present as Guest of Honor. He’s well worth meeting, not only because he’s a swell guy, but for his knowledge of fantasy and THE FIRST MEN ON THE MOON FORREST J. -

Fahrenheit 451

FAHRENHEIT 451: A DESCRIPTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY Amanda Kay Barrett Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of English, Indiana University May 2011 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. __________________________________________ Jonathan R. Eller, Ph.D., Chair Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________________ William F. Touponce, Ph.D. __________________________________________ M. A. Coleman, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my wonderful thesis committee, especially Dr. Jonathan Eller who guided me step by step through the writing and editing of this thesis. To my family and friends for encouraging me and supporting me during the long days of typing, reading and editing. Special thanks to my mother, for being my rock and my role model. To the entire English department at IUPUI – I have enjoyed all these years in your hands and look forward to being a loyal and enthusiastic alumna. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Narrative Introduction ..........................................................................................................1 Genealogical Table of Contents .........................................................................................17 Fahrenheit 451: A Descriptive Bibliography .....................................................................24 Primary Bibliography.........................................................................................................91 -

The A. Heinlein Centennial July 5 to 8, 2007

The A. Heinlein Centennial July 5 to 8, 2007 he Centennial celebration of Robert A Heinlein's birth took place in Kansas City over the period from Thursday July 5 to Sunday July 8, 2007, attended by about 750 members of the Hcinlein community- TThe Centennial celebration was mounted by an ad hoc committee incorporated as Ileirdcin Centennial, Inc It was our goal to bring together as many different facets of the Heinlein community In one place as could be managed, and we are happy to report a resounding success. I he response of both the commercial and the government space community were very gratifying — and quite unlooked for. The gala itself, preceded by a buffet dinner, took place on Ileinlcm's hundredth birthday, which he had thoughtfully scheduled to fall on Saturday in his centennial year — and as Peter Scott emarked "Heinlein also had the foresight to schedule his centenary before the economy went in Ihe ci appcr " 1 hat last is perhaps more than a throw-away joke in the opening years of the Greater Depression; you will find throughout the comments by organizers and attendees oblique references to financial crises and a fantastic degree of sabotage by the organisation that should have been doing the Centennial but was not, Sketches of fuller tellings of the story have been archived on the Heinlein Nexus Forum but would overrun the space available in the JOURNAL, The remembrances of the participants are an embarrns tic ridiesscs. THE PROGRAM COMMENTS BY ORGANIZERS AND ATTENDEES: TllURSJMYjUIYS arly in 2009, Founding organizer of the Centennial, James O Ciffoid, announced on the newly established Heinlein Noon - 6:00 PM ENexus Forum that the Centennial's sponsoring organisa- SHR A Registration tion, Ileinlcin Centennial, Inc , was winding up its affairs. -

Carroll & Graf

CARROLL & GRAF ARROLL &GRAF 260 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10001 (212) 889-8772 CONTENTS PAGE PAGE Anonymous, The Erotic Reader Ill 41 Kometani, Foumiko, Passover 8 The Libertines 41 Lovesey, Peter, The Black Cabinet 24 The Oyster Ill 41 Parisian Nights 41 Madden, David & Peggy Bach, Satanic Venus 41 Rediscoveries II 33 Ball. John, The Kiwi Target 4 Malzberg, Barry. Beyond Apollo 22 Ballard. J.C.. Hello America 13 Marrs, Jim, Crossfire 15 Ballard, Mignon F., Deadly Promise . 19 Maurlac, Francois, Flesh and Blood 26 Balzac, lirmore de, [Matrix . 30 McElroy, Joseph, The Letter Left to Me 39 Beechcroft, William, Pursuit of Fear . 31 O'Mara. Lesley, Great Cat Tales 10 Boucher, Anthony. The Complex! Pentecost. Hugh. Pattern for Terror . 35 Werewolf 33 Phillips, Robert, The Triumph of the Brand, Christianna, Death in High Night 5 Heels . 6 Reeky, John, Marilyn's Daughter 20 Brown, Fredric, Murder Can Be Fun 27 Rhys, Jean, Quartet 36 Carr, John Dickson, Schul, Bill D., Animal Immortality 39 The Demoniacs 28 Sladek, John, The Midler-Fokker Effect Most Secret 14 40 Da, Lottie & Jan Alexander, Bad Girls of Stanway, Dr. Andrew, The Art of Sensual Loving the Silver Screen 16 13 Thirkell, Angela, Wild Strawberries . Dalby, Richard, Ghosts for Christmas 18 7 Thornton, Louise, et al.. Touching Fire Dick, Philip 1C.. The Zap Gun 7 25 van Thal, Herbert, The Mammoth Book of Fitzgerald. Penelope, Innocence 20 Great Detective Stories 12 Freudenberger, Dr. Herbert. Situational von Falkensee, Margarete, Blue Angel Anxiety 6 Secrets 2121 Garbus, Martin. Traitors and Heroes 26 Watson.Secrel Gilbert. -

Hubbard Bubble, Dianetics Trouble

SGOXXX10.1177/2158244018807572SAGE OpenMenadue 807572research-article20182018 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University Original Research SAGE Open October-December 2018: 1 –19 Hubbard Bubble, Dianetics Trouble: © The Author(s) 2018 https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018807572DOI: 10.1177/2158244018807572 An Evaluation of the Representations journals.sagepub.com/home/sgo of Dianetics and Scientology in Science Fiction Magazines From 1949 to 1999 Christopher Benjamin Menadue1 Abstract Dianetics was unveiled to the public in the May 1950 edition of Astounding Science Fiction. Dianetics was the brainchild of science fiction author L. Ron Hubbard, and became the foundation for scientology toward the end of the decade. Dianetics was marketed as a “scientific” method for mental improvement—a robust alternative to conventional psychiatry—and was strongly debated in science fiction (sf) magazines. This article follows the trajectory of this cultural phenomenon from 1949 to 1999 as it appeared in this form of popular culture. A proximal reading method was applied to analyze 4,431 magazines, and identified 389 references to dianetics and scientology. References were found in advertising, reader letters, stories, feature articles, and editorials. Significant fluctuations in the prominence and perception of dianetics became clearly visible in the source material across a broad spectrum of content. Negative criticism was present from the outset, and based on logical and scientific arguments. This was countered by obfuscation, or attacks on the authors of these critiques. The followers and promoters of dianetics did not provide scientifically rigorous proof of their claims, and by the mid-1980s, dianetics and scientology were no longer serious topics in the magazines but had been added to other fads and fallacies of sf history. -

NEW FRONTIERS NEW Hlomnibs

NEW FRONTIERS NEW HlOMniBS. August i960. Voluao 1. Nuaber 3 Cover George Barr Good Science Fiction — GOOD SCIENCE FICTION — WHERE IS ITT Daaon Knight 3 ARXHAH HOUSE ENTERS ITS THIRD DECADE August I>rloth 8 Damon Knight SHERLOCK HOLMES AND SCIENCE FICTION Anthony Boucher 10 Where Is It? illustrated by Tea Walker On the SF Screen Miko Decklngor 15 I7th *,rld Flcu“ Con”"u»' The Cold Eye Arthur Wilcox 17 asked to speak. I wrotr^SroUor^s“v“2n^3“Xer on^ subjict^ Ud Forthrightly lou (we hope) 20 Books The Staff + Poul Anderson, Bjo, 33 Ted White, Jases Hlish 4 (toy Before I get into that, though, there’s something I have to exnlain Hunt. that^^T^ ln ,933’ 1 vaa roa^^ld^ And^T h ‘ oIhJOk<ht * Of * aclonco fiction nagaeino, and it hooked ao. I Editorial The Editor 55 »• covert - ^p£ btoTp^d^ Back Cover George Barr vlndlJr’ considering that this magazine Is twenty-six years Editor - .'<ohb Metcalf Expatriate Associate Editor - Bill Collins Expatriate Assistant Editor - Bill Shopes New Frontiers is published irregularly by Terra House, P.O. Box 336, Berkeley 1, California. Editorial address is Box 1262, Tyndall AFB, Florida. tables evo^thlne need out of solidified gas — Subscription rates: 4 issues for $1.00, single copies 30# (in the U.S. and Canada) England: 4 issues for 7/-. single copies 2/- to Jaes Groves, 29 Lathoa Road, East Han, London, 1.6., Fhgland Australia: 4 issues for 10/-. single copies 3/- to Donald H. Tuck, 139 East Riodon Road. LINDISFARNE, Tasaumia, Australia Sweden: 5 issues for 5 kronor, single copies 1 krona to Vpl 410722-49 C.