Book Reviews from the Sf Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

Rereading Philip K. Dick

REFLECTIONS Robert Silverberg REREADING PHILIP K. DICK They were ugly little things. I mean the tner. Dick was only twenty-seven when first editions of Philip K. Dick’s first nov- Solar Lottery came out, a youthful begin- els—squat, scrunchy, cheaply printed ner who had appeared in the science fic- 1950s paperbacks, artifacts of a primitive tion magazines just three years before era in science fiction publishing. Ace with a double handful of ingenious short Books was the name of the publishing stories. I had already begun to sell some company—they are still in business, stories myself in 1955, so in terms of ca- though vastly transformed—and Ace reer launch we were virtually contempo- writers then were paid one thousand dol- raries, but I was only twenty, a college ju- lars per novel, which even then was the nior, and that seven-year gap in our ages bottom rate for paperback books, al- made me regard Dick as vastly older, though in modern purchasing power it’s vastly wiser, vastly more skillful in the a good deal more than most new SF writ- art of storytelling. I was an earnest be- ers can command today. ginner; he was already a pro. Still, there were harbingers of things to He was good, all right. But I don’t come in those early Dick books. The very think either of us realized, back there in first sentence of the very first one tells us 1955, that he was destined to make an that in the most literal way: “There had imperishable mark on American popular been harbingers.” That’s Solar Lottery, culture. -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick

EUGÊNIA BARTHELMESS Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- Graduação em Letras, Área de Concentra- ção Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, do Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federai do Paraná, como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre. Orientadora: Prof.3 Dr.a BRUNILDA REICHMAN LEMOS CURITIBA 19 8 7 OF PHILIP K. DICK ERRATA FOR READ p -;2011 '6:€h|j'column iinesllll^^is'iiearly jfifties (e'jarly i fx|fties') fifties); Jl ' 1 p,.2Ò 6th' column line 16 space race space race (late fifties) p . 33 line 13 1889 1899 i -,;r „ i i ii 31 p .38 line 4 reel."31 reel • p.41 line 21 ninteenth nineteenth p .6 4 line 6 acien ce science p .6 9 line 6 tear tears p. 70 line 21 ' miliion million p .72 line 5 innocence experience p.93 line 24 ROBINSON Robinson p. 9 3 line 26 Robinson ROBINSON! :; 1 i ;.!'M l1 ! ! t i " i î : '1 I fi ' ! • 1 p .9 3 line 27 as deliberate as a deliberate jf ! •! : ji ' i' ! p .96 lin;e , 5! . 1 from form ! ! 1' ' p. 96 line 8 male dis tory maledictory I p .115 line 27 cookedly crookedly / f1 • ' ' p.151 line 32 why this is ' why is this I 1; - . p.151 line 33 Because it'll Because (....) it'll p.189 line 15 mourmtain mountain 1 | p .225 line 13 crete create p.232 line 27 Massachusetts, 1960. Massachusetts, M. I. T. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

Panel About Philip K. Dick

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Andrew M. Butler and David Hyde July 2018 Andrew M. Butler is a British academic who teaches film, media and cultural studies at Canterbury Christ Church University. His thesis paper for his PhD was titled “Ontology and ethics in the writings of Philip K. Dick.” He has also published “The Pocket essential Philip K. Dick”. He is a former editor of Vector, the Critical Journal of the British Science Fiction Association and was membership secretary of the Science Fiction Foundation. He is a former Arthur C. Clarke Award judge and is now a member of the Serendip Foundation which administers the award. David Hyde, a.k.a. Lord Running Clam, joined the Philip K. Dick Society in 1985 and contributed to its newsletter. When the PKDS was discontinued, he created For Dickheads Only in 1993, a zine that was active until 1997. Since then, his activities include many contributions to and editorial work for the fanzine PKD OTAKU. His book, PINK BEAM: A Philip K. Dick Companion, is a detailed publication history of PKD's novels and short stories. In 2010, David organized the 21st century's first Philip K. Dick Festival in Black Hawk, Colorado. Recently, in partnership with Henri Wintz at Wide Books, he has published two full-color bibliographies of the novels and short stories of Philip K. Dick. In early 2019 Wide Books will publish the French bibliography. On the 35th anniversary of Phil’s passing in 2017 David held a memorial celebration for PKD fans in Ft. Morgan, Colorado, the final resting place of Phil and his twin sister Jane. -

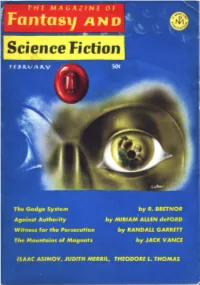

This Month's Issue

FEBRUARY Including Venture Science Fiction NOVELETS Against Authority MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD 20 Witness for the Persecution RANDALL GARRETT 55 The Mountains of Magnatz JACK VANCE 102 SHORT STORIES The Gadge System R. BRETNOR 5 An Afternoon In May RICHARD WINKLER 48 The New Men JOANNA RUSS 75 The Way Back D. K. FINDLAY 83 Girls Will Be Girls DORIS PITKIN BUCK 124 FEATURES Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 19 Books JUDITH MERRIL 41 Desynchronosis THEODORE L. THOMAS 73 Science: Up and Down the Earth ISAAC ASIMOV 91 Editorial 4 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by George Salter (illustrating "The Gadge System") Joseph W. Ferman, PUBLISHER Ed~mrd L. Fcrma11, EDITOR Ted White, ASSISTANT EDITOR Isaac Asimov, SCIENCE EDITOR Judith Merril, BOOK EDITOR Robert P. llfil/s, CONSULTING EDITOR The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Volnme 30, No. 2, Wlrolc No. 177, Feb. 1966. Plfblished monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 50¢ a copy. Aunual subscription $5.00; $5.50 in Canada and the Pan American Union, $6.00 in all other cormtries. Publication office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N.H. 03302. Editorial and ge11eral mail sholfld be sent to 3/7 East 53rd St., New York, N. Y. 10022. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N.H. Printed in U.S.A. © 1965 by Mercury Press, Inc. All riglrts inc/fl.ding translations iuto ot/rer la~>guages, resen•cd. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed ent•ciBPes; tire Publisher assumes no responsibility for retlfm of uusolicitcd ma1111scripts. BDITOBIAL The largest volume of mail which crosses our desk each day is that which is classified in the trade as "the slush pile." This blunt term is usually used in preference to the one y11u'll find at the very bottom of our contents page, where it says, ". -

Fanscient 12

fflnsciEriT• No. 12 SUMMER, 1950 | Three years and 400 pages ago, we brought out the first issue of The FANSCIEOT. This issue completes the third year, and just under the wire too, as it’s nearly three months late. For this 1 decline to Volume 4, Whole Number 12 apologize as only one who was idiot enough to accept the chairmanship of a world stf-con would be putting out an issue even'now. Those few Number 2. tfefflnsciEnj SUMMER, 1950 who have been the chairmen or work-horses of past cons will know what I mean---- the rest of you will just have to imagine as best you can. Even now, there would be no issue save for the valiant efforts of CONTENTS of the SUMMER 1950 Issue Miles Eaton, who with his wife, Betty, prepared much of the copy for publication and Jim Bradley, who nobly assisted in the final preparation of the issue. Incidentally, Jim’s fanzine, DESTINY, is going lithoed COVER Photo from DESTINATION MOON with its second issue, ready now. 16 lithoed Fanscient-sized pages for 150. Order from Jim Bradley, 545 NE San Rafael St., Portland 12, Ore. UNBELIEVITUDINOSITY JOHN & DOROTHY DE COURCY 4 Illustrated by J. M. Higbee After reading Anthony Boucher’s autobiography in the AUTHOR, AUTHOR department, I’m sure you’ll be ready to come up to the NORWESCON where OUT OF LEGEND: The Babd Catha Text dt Picture by MILES EATON 8 Tony will be present as Guest of Honor. He’s well worth meeting, not only because he’s a swell guy, but for his knowledge of fantasy and THE FIRST MEN ON THE MOON FORREST J. -

PKD Otaku # 12 - February 2004 1 a Question of Chronology: 1955 – 1958 Frame

"SCOTT MEREDITH TO PKD" September 30 [1968] Dear Phil, Thanks very much for our letter. Doubleday can't yet release the full $4500 because the money hasn't come in yet from NAL. We have asked them to advance some -- up to $1500 -- and we're confident this will be coming in very soon. In the meantime, I'm happy to send you a check for the $1500, less commission, as our advance on the Doubleday money. Here, then, is $1350. Doubleday, of course, is very anxious to see the new book you've mentioned to us and to Larry, and if you could send in a completed half, say in two weeks or so, they'll be able to issue an immediate contract. And, of course, they're very anxious about DEUS IRAE, mostly because they'd like to contract for THE NAME OF THE GAME IS DEATH as soon as possible, but cannot until they have something more on DEUS IRAE. This is necessary because GAME in only in outline form, whereas the new one is completed in rough draft. Now I'd like to pass on some very encouraging news from Norman Spinrad -- we know you've been talking to him about this -- that the editor at Essex House is very interested in seeing some of your old unpublished novels. They are of course moving out of the sex lines and the editor is an old S-F fan. They would pay from $1000 to $1500 for any they might want to do. By all means, send in these old ones and we'll be happy to push for you in his area. -

Fahrenheit 451

FAHRENHEIT 451: A DESCRIPTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY Amanda Kay Barrett Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of English, Indiana University May 2011 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. __________________________________________ Jonathan R. Eller, Ph.D., Chair Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________________ William F. Touponce, Ph.D. __________________________________________ M. A. Coleman, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my wonderful thesis committee, especially Dr. Jonathan Eller who guided me step by step through the writing and editing of this thesis. To my family and friends for encouraging me and supporting me during the long days of typing, reading and editing. Special thanks to my mother, for being my rock and my role model. To the entire English department at IUPUI – I have enjoyed all these years in your hands and look forward to being a loyal and enthusiastic alumna. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Narrative Introduction ..........................................................................................................1 Genealogical Table of Contents .........................................................................................17 Fahrenheit 451: A Descriptive Bibliography .....................................................................24 Primary Bibliography.........................................................................................................91 -

Psychological Terror and Social Fears in Philip K. Dick's Science Fiction

Belphégor Giuliano Bettanin Psychological Terror and Social Fears in Philip K. Dick's Science Fiction As it developed during the twentieth century, the genre of science fiction has often used themes belonging to horror literature. In point of fact, these two genres have a good deal in common. Most obviously, science fiction and horror share a fantastic background and a detachment from the probabilities of realistic fiction. Also, the birth of science fiction is closely connected to the development of the gothic novel. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, which is commonly considered proto-science fiction, also represents a nineteenth-century development of the gothic novel. In addition, Herbert George Wells, whose work lies at the basis of modern science fiction, wrote at least one gothic novel, The Island of Doctor Moreau.1 The fusion of horror and science fiction has often generated figures of terrifying and evil aliens, robots that rebel against their human creators, and apocalyptic, post-thermonuclear-global-war scenarios. In this brief essay I shall analyze the ways in which Philip K. Dick incorporated horror themes into his oeuvre and the highly original results he obtained by mingling the two genres. For this purpose I shall discuss several of his short stories and his early novel Eye in the Sky. Besides the already mentioned motifs of the alien, the rebel robot and the atomic holocaust, Dick develops a mystical-religious motif as he explores a number of metaphysical problems that are strictly connected to his most characteristic interest in epistemological questions. From the moment of the publication of his first short stories and novels in the 1950s, Dick became one of the most representative authors of American social science fiction. -

Dick's First Novel

On SF by Thomas M. Disch http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=124446 The University of Michigan Press, 2005 Dick’s First Novel There are, by now, many science ‹ctions, but for myself (for any reader) there is only one science ‹ction—the kind I like. When I want to ‹nd out if someone else’s idea of sf corresponds signi‹cantly with mine (and whether, therefore, we’re liable to enjoy talking about the stuff), I have a simple rule-of-thumb: to wit—do they know—and admire—the work of Philip K. Dick? An active dislike, as against mere ignorance, would suggest either of two possibilities to me. If it is expressed by an otherwise voracious con- sumer of the genre, one who doesn’t balk at the prose of Zelazny, van Vogt, or Robert Moore Williams, I am inclined to think him essentially un-serious, a “fan” who is into sf entirely for escapist reasons. If, on the other hand, he is provably a person of enlightenment and good taste and he nevertheless doesn’t like Dick, then I know that my kind of sf (the kind I like) will always remain inaccessible. For those readers who require sf always to aspire to the condition of art Philip Dick is just too nakedly a hack, capable of whole chapters of turgid prose and of bloopers so grandiose you may wonder, momentarily, whether they’re not just his lit- tle way of winking at his fellow-laborers in the pulps. Even his most well- realized characters have their moments of wood, while in his bad novels (which are few), there are no characters, only names capable of dialogue.