Clean Waters, Healthy Habitats (2001)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Toronto Islands Flood Characterization and Risk Assessment Project Flood Risk Assessment Report

Toronto Islands Flood Characterization and Risk Assessment Project Flood Risk Assessment Report 30 April 2019 | 13017.101.R2.Rev0_FloodRisk Toronto Islands Flood Characterization and Risk Assessment Project Flood Risk Assessment Report Prepared for: Prepared by: Toronto and Region Conservation Authority W.F. Baird & Associates Coastal Engineers Ltd. 101 Exchange Avenue Vaughan, Ontario For further information, please contact L4K 5R6 Josh Wiebe at +1 905 845 5385 [email protected] www.baird.com 13017.101.R2.Rev0_FloodRisk Z:\Shared With Me\QMS\2019\Reports_2019\13017.101.R2.Rev0_FloodRisk.docx Revision Date Status Comments Prepared Reviewed Approved A 2018/02/12 Draft Client Review DJE JDW RBN 0 2018/04/30 Final Final Report JDW RBN RBN © 2019 W.F. Baird & Associates Coastal Engineers Ltd. (Baird) All Rights Reserved. Copyright in the whole and every part of this document, including any data sets or outputs that accompany this report, belongs to Baird and may not be used, sold, transferred, copied or reproduced in whole or in part in any manner or form or in or on any media to any person without the prior written consent of Baird. This document was prepared by W.F. Baird & Associates Coastal Engineers Ltd. for Toronto and Region Conservation Authority. The outputs from this document are designated only for application to the intended purpose, as specified in the document, and should not be used for any other site or project. The material in it reflects the judgment of Baird in light of the information available to them at the time of preparation. Any use that a Third Party makes of this document, or any reliance on decisions to be made based on it, are the responsibility of such Third Parties. -

Is Toronto Fiscally Healthy? a Check-Up on the City’S Finances

IMFG No. 7 / 2014 perspectives The Pre-Election Series Is Toronto Fiscally Healthy? A Check-up on the City’s Finances Enid Slack and André Côté About IMFG The Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance (IMFG) is an academic research hub and non-partisan think tank based in the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto. IMFG focuses on the fiscal health and governance challenges facing large cities and city-regions. Its objective is to spark and inform public debate, and to engage the academic and policy communities around important issues of municipal finance and governance. The Institute conducts original research on issues facing cities in Canada and around the world; promotes high-level discussion among Canada’s government, academic, corporate and community leaders through conferences and roundtables; and supports graduate and post-graduate students to build Canada’s cadre of municipal finance and governance experts. It is the only institute in Canada that focuses solely on municipal finance issues in large cities and city-regions. IMFG is funded by the Province of Ontario, the City of Toronto, Avana Capital Corporation, and TD Bank Group. Authors Enid Slack is the Director of the IMFG. André Côté is the Manager of Programs and Research. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Paul Bedford, Richard Bird, Kyle Hanniman, Zac Spicer, and Zack Taylor for their thoughtful comments on the draft paper, and staff at the City of Toronto and Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing for their assistance with data collection. The authors alone are responsible for the contents of the paper and the opinions expressed, which are not attributable to the IMFG or its funders. -

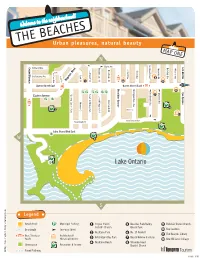

90Ab-The-Beaches-Route-Map.Pdf

THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP ONE N Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Coxw Dixon Ave Bell Brookmount Rd Wheeler Ave Wheeler Waverley Rd Waverley Ashland Ave Herbert Ave Boardwalk Dr Lockwood Rd Elmer Ave efair Ave efair O r c h ell A ell a r d Lark St Park Blvd Penny Ln venu Battenberg Ave 8 ingston Road K e 1 6 9 Queen Street East Queen Street East Woodbine Avenue 11 Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Kippendavie Ave Kippendavie Ave Waverley Rd Waverley Sarah Ashbridge Ave Northen Dancer Blvd Eastern Avenue Joseph Duggan Rd 7 Boardwalk Dr Winners Cir 10 2 Buller Ave V 12 Boardwalk Dr Kew Beach Ave Al 5 Lake Shore Blvd East W 4 3 Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking Corpus Christi Beaches Park/Balmy Bellefair United Church g 1 5 9 Catholic Church Beach Park 10 Kew Gardens . Desi Boardwalk One-way Street d 2 Woodbine Park 6 No. 17 Firehall her 11 The Beaches Library p Bus, Streetcar Architectural/ he Ashbridge’s Bay Park Beach Hebrew Institute S 3 7 Route Historical Interest 12 Kew Williams Cottage 4 Woodbine Beach 8 Waverley Road : Diana Greenspace Recreation & Leisure g Baptist Church Writin Paved Pathway BEACH_0106 THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP TWO N H W Victoria Park Avenue Nevi a S ineva m Spruc ca Lee Avenue Kin b Wheeler Ave Wheeler Balsam Ave ly ll rbo Beech Ave Willow Ave Av Ave e P e Crown Park Rd gs Gle e Hill e r Isleworth Ave w o ark ark ug n Manor Dr o o d R d h R h Rd Apricot Ln Ed Evans Ln Blvd Duart Park Rd d d d 15 16 18 Queen Street East 11 19 Balsam Ave Beech Ave Willow Ave Leuty Ave Nevi Hammersmith Ave Hammersmith Ave Scarboro Beach Blvd Maclean Ave N Lee Avenue Wineva Ave Glen Manor Dr Silver Birch Ave Munro Park Ave u Avion Ave Hazel Ave r sew ll Fernwood Park Ave Balmy Ave e P 20 ood R ark ark Bonfield Ave Blvd d 0 Park Ave Glenfern Ave Violet Ave Selwood Ave Fir Ave 17 12 Hubbard Blvd Silver Birch Ave Alfresco Lawn 14 13 E Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking g 13 Leuty Lifesaving Station 17 Balmy Beach Club . -

Background of Responders and Emergency Management

CHAPTER Background of Responders and Emergency Management Emergency management in Ontario . 8 Graduated problem solving and emergency response ........................................... 8 The role of the municipality ..................................................................... 9 The municipal emergency management program .................................................. 9 Municipal emergency control groups ............................................................ .10 Municipal emergency management program coordinator and committee ........................... .11 Declaration of an emergency by the municipality ................................................. .11 Community emergency operations centres ....................................................... 11 Mutual aid system and municipal capacity expectations ........................................... .12 Volunteers .................................................................................... .12 The role of the province ........................................................................ .13 Premier of Ontario ............................................................................. .13 Lieutenant governor in council .................................................................. 13 Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services ........................................... .13 Provincial Emergency Response Plan ............................................................ .15 The Provincial Emergency Response Plan for Building Structural Collapse -

Performance Assessment of the Eastern Beaches Detention Tank - Toronto, Ontario

Performance Assessment of the Toronto Eastern Beaches Detention Tank - Toronto, Ontario 2004 PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT OF THE EASTERN BEACHES DETENTION TANK - TORONTO, ONTARIO a report prepared by the STORMWATER ASSESSMENT MONITORING AND PERFORMANCE (SWAMP) PROGRAM for Great Lakes Sustainability Fund Ontario Ministry of the Environment Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Municipal Engineers Association of Ontario City of Toronto July, 2004 © Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Performance Assessment of the Toronto Eastern Beaches Detention Tank NOTICE The contents of this report are the product of the SWAMP program and do not necessarily represent the policies of the supporting agencies. Although every reasonable effort has been made to ensure the integrity of the report, the supporting agencies do not make any warranty or representation, expressed or implied, with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation of those products. No financial support was received from developers, manufacturers or suppliers of technologies used or evaluated in this project. An earlier version of this report and various memoranda on specific technical issues related to this project were prepared by SWAMP. Additional data analysis and interpretation, probabilistic modeling and report editing/writing were undertaken by Lijing Xu and Barry J. Adams from the University of Toronto’s Department of Civil Engineering under contract to the SWAMP program, as represented by the City of Toronto. PUBLICATION INFORMATION Documents in this series are available from the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority: Tim Van Seters Water Quality and Monitoring Supervisor Toronto and Region Conservation Authority 5 Shoreham Drive, Downsview, Ontario M3N 1S4 Tel: 416-661-6600, Ext. -

Along the Shore: Rediscovering Toronto's Waterfront Heritage ― Interviews the Following Is a Selection of Interviews I Condu

Along the Shore: Rediscovering Toronto’s Waterfront Heritage ― Interviews The following is a selection of interviews I conducted during the course of research for Along the Shore, including interviews that I referred to in the text. SCARBOROUGH Jane Fairburn. Interviews with: John Alexander, Scarborough resident, May 2011. Kevin Brown, former Scarborough resident, May 2011. Telephone interview. Paul Burd, Scarborough resident, May 2011. Ian Campbell, Scarborough resident, January 2009, November 2011, January 2013. Telephone interview. Margaret Carr (née Heron), former Scarborough resident, summer 2000. Telephone interview. Nancy Gaffney, Waterfront Specialist, Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, June and November 2011. Telephone interview. Professor Richard Harris, School of Geography and Life Sciences, McMaster University, April 2011. Telephone interview. Herb Harvey, Scarborough resident, May 2011. Sue Johanson, author, nurse, and sex educator, September 2012. Telephone interview. Margie Kenedy, Senior Archaeologist, Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, June 2011. Telephone interview. Barbara (neé Beech) Kennedy, Scarborough resident, January 2009 and May 2011. Professor Victor Konrad, archaeologist, University of Ottawa, July 2011. Telephone interview. Raimund Krob, President, Ontario Underwater Council, Toronto, 2009. Telephone interview. Sherri Lange and Michael Spencely, Scarborough residents, May 2011. Denis Matte, General Manager, Scarboro Golf and Country Club, August 2011. Telephone interview. Doris McCarthy, Canadian landscape painter and Scarborough resident, June 2000. Robert McCowan, Scarborough resident, June 2000, October 2008, and September 2011. Robert Pollock, Scarborough resident, June 2000 and April 2009. Dana Poulton, archaeologist, D. R. Poulton and Associates Inc., (email correspondence, November 2011 and February 2013). Phil Richards, artist and Scarborough resident, June 2000. Margaret Sault, Director of Lands, Membership and Research, Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation, July 8, 2011. -

Appendix 1: Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport Capital Program 2019 Update

Appendix 1: Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport Capital Program 2019 Update Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport Capital Program 2019 Update Date: May 1, 2019 Presented By: Bojan Drakul / Christopher Sawicki Location: CLC Presentation Agenda • Review Status of Ongoing and Upcoming 2019 Capital Projects by PortsToronto • Review 2019 Projects by Airport Tenants 2 Overview - Five Year Capital Plan for 2019 to 2023 was approved by the Board in January - This year’s program is not as extensive compared to previous years - Sustainability and environmental protection continue to be at forefront of all our project developments 3 Remaining 2018 • Minor electrical deficiencies work • A few remaining pavement / grading Projects items to be completed shortly (weather dependent) – night work Airfield Rehabilitation Program 4 • Update to airport access including improvements to traffic flow and passenger experience • Storm water management updates • Coordinated with Bathurst Quay Neighbourhood Plan and Dockwall Repair including Record of Site Condition for change of land use from industrial to parks and open space • Construction start in early Summer City Side Modernization 5 2019 Projects • Drainage improvements to be made to reduce risk of flooding of the PTF facility • Design underway with construction in the summer 2019 • Construction details yet to be developed Drainage Improvements at Airport Turning Circle 6 • The project includes stabilization and repair of the c.1913 dockwall • Following repair, construction of public boardwalk and greenspace will -

Toronto Water Budget Briefing Presentation

Toronto Water 2021 Operating Budget and 2021-2030 Capital Budget & Plan 2021 Water Rate Briefing to Budget Committee November 6, 2020 Toronto Water • Toronto Water manages one of the largest utilities in North America, operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week. • We serve 3.6 million residents and businesses in Toronto, and portions of York and Peel protecting public health, safety and property in an environmentally and a fiscally responsible manner. • The following services are delivered to Toronto residents, businesses and visitors: Safe drinking water Wastewater collection and treatment Stormwater management Overview Description What Services We Provide Water Treatment & Supply Toronto Water manages one of the largest water, wastewater and stormwater systems in North America, 24 hours a day, seven days a Who We Serve: Water account holders, water consumers week. Toronto Water's services ensure that over 3.6 million residents and What We Deliver: Supply +435 billion litres annually of safe potable water. businesses in Toronto, and portions of York and Peel have access to safe Continuous distribution of potable water through +6,100 km of watermains and drinking water, safely treated wastewater and stormwater management. City-owned water services. How Much Resources (gross operating budget): $196 Million (2021) Wastewater Collection & Treatment Who We Serve: Wastewater account holders, wastewater producers, public & private landowners What We Deliver: Return to Lake Ontario +400 billion litres annually of treated Why We Do It wastewater. Continuous conveyance of wastewater through +5,100 km of Drinking water is delivered to people (residents, businesses, visitors and the sewers. Industrial, Commercial, Institutional sector in Toronto and York Region) in a safe How Much Resources (gross operating budget): $230 Million (2021) and reliable manner to protect public health. -

FIG.1 Water Supply Sources and Sewage Treatment Plants, 1949

FIG.1 Water Supply Sources and Sewage Treatment Plants, 1949 Map drawn by Gore & Storrie for their 1949 report to the Toronto and York Planning Board SOURCE: Gore & Storrie,“Toronto and York Planning Board Report on Water Supply and Sewage Disposal for the City of Toronto and Related Areas’‘, September 1949 (UAL) FIG.2 Metropolitan Toronto Sewage System Plan, 1954 Map shows existing system and initial plans for expansion. SOURCE: Metropolitan Toronto Annual Report, 1954 (UAL) FIG.3 Metropolitan Toronto Water Supply System Plan, 1954 Map shows existing system and initial plans for expansion. SOURCE: Metropolitan Toronto Annual Report, 1954 (UAL) FIG.4 Metropolitan Toronto Road System Plan, 1954 Map shows existing and proposed expressways, and arterial roads taken over by the Metropolitan Toronto corporation upon its creation. SOURCE: Metropolitan Toronto Annual Report, 1954 (UAL) FIG.5A East Don Sewer Area, 1947 SCALE 1 : 50000 O O.5 1 KM N Steeles Ave Victoria Park Ave ➤ Woodbine Ave Leslie St Bayview Ave Yonge St Finch Ave Sheppard Ave York Mills Ave DEVELOPMENT WATER SERVICES SEWAGE SERVICES Roads and Highways Water Treatment Plant Area Served by Local Sewage Plants Railroad Water Storage Tank Commercial Building Well Unclassified Building Trunk Water Line Street Grid of Residental Development (individual houses not shown) NOTES • Water from Leslie Street wells treated at Oriole plant • No sewer service east of Bayview Avenue SOURCES: Ontario Base Maps, 1 : 10,000; City of Toronto Archives Fonds 9, Series 12, Aerial Photography of the -

Calls for Suspected Opioid Overdoses Geographic Information

TORONTO OVERDOSE INFORMATION SYSTEM Prepared by Toronto Public Health August 2018 Calls to Paramedic Services for Suspected Opioid Overdoses Geographic Information Key Messages: Data from Toronto Paramedic Services (TPaS) show that the highest concentration of calls for suspected opioid overdoses were in the downtown area over the past year. The top five neighbourhoods and top ten main intersections with the highest number of calls were all in the downtown area, bounded roughly by Bathurst Street to the West, Bloor Street to the North, the Don Valley Parkway to the East, and Lake Ontario to the south. However, opioid overdoses are occurring all across Toronto. Other areas where TPaS responded to calls included to the east and west of the downtown core, and parts of Etobicoke, North York, and Scarborough. Please review the Data Notes section for more information. This information will be posted online and updated on a regular basis at www.toronto.ca/health/overdosestats. Data Notes: • Information is preliminary and subject to change pending further review of the data source. • The data provided in this document includes only instances where 911 is called and likely underestimates the true number of overdoses in the community. • The data include cases where the responding paramedic suspects an opioid overdose. This may differ from the final diagnosis in hospital or cause of death determined by the coroner. • The information in this report refers to the total number of calls (i.e. fatal and non- fatal cases combined). Over the one-year period, there were 3,197 calls with valid geographic information occurring within the boundaries of the City of Toronto. -

Eastern Ravine & Beaches

GETTING THERE AND BACK Follow ravine footpaths and a 2 BEACHES NEIGHBOURHOOD You can reach the suggested starting point on beach boardwalk. Experience a public transit by taking the 64 MAIN bus south During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the from Main Street Station on the BLOOR/ Great Lake shoreline, gardens Beaches was one of the most popular beach DANFORTH subway line and get off at Kingston and wooded ravine parklands. resorts in the region and contained several Road. The 501 QUEEN streetcar east from amusement parks. Exploring the tree-lined streets Queen Station on the YONGE/UNIVERSITY THE ROUTES today, the architecture, atmosphere and attitude of this community still resembles a small lakeside subway line also provides service into the area EASTERN RAVINES DISCOVERY WALK resort town. Plan a return visit to check out all the including one of the suggested tour end points. Eastern Although you can begin this Discovery unique and eclectic storefronts, boutiques, cafes Walk at any point along the route, a and restaurants along Queen St. East. You never good starting point is the northern end know what you will discover! FOR MORE INFO Ravine & of the enchanting Glen Stewart Ravine (see top of map). Follow this ravine down to the Lake Discovery Walks is a program of self-guided Ontario shore and experience the Eastern 3 BOARDWALK walks that link city ravines, parks, gardens, Beaches and its boardwalk. Along the way you’ll Boardwalks have existed along this shoreline beaches and neighbourhoods. For more Beaches visit an Art Deco water treatment plant and a since 1850.