Bacon – Giacometti April 29 – September 2, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diego Giacometti 1901-1985

Diego Giacometti 1901-1985 La promenade des amis Tapis en laine, édition à 100 exemplaire, 1984 Dimensions : 240 x 175 cm Dimensions : 94.49 x 68.90 inch 32 avenue Marceau 75008 Paris | +33 (0)1 42 61 42 10 | +33 (0)6 07 88 75 84 | [email protected] | galeriearyjan.com Diego Giacometti 1901-1985 Biography Young brother of Alberto Giacometti, Diego grew up in Stampa in the family farm where his father Giovanni Giacometti - Swiss post-impressionist and Fauvism painter - used to make their daily furniture. By the way, the father introduced the young boy to art. From a solitary nature, Diego shared his childhood with animals in the village and the farm. This privileged relation with animals will always guide him during his artistic life. Diego Giacometti was resistant to studies and preferred to pose for his eldest brother instead of going to school. After mediocre studies, he lived a travelling life from 1919. He especially travelled to Egypt where the symbolism of the cat left its mark on his future works. In 1925, he settled in Paris and joined his brother Alberto who was studied sculpture with Antoine Bourdelle. The first years were especially difficult for Diego who only found sporadic jobs in factories or offices. In 1927, Alberto found a little sculptor's studio. From then on, Diego will constantly be his co-worker. Beyond his exceptional savoir-faire and his indisputable manual dexterity he also brought some ideas. He assisted his brother by creating some bases and display stands for his sculptures. This is how he turned almost naturally to furniture's making. -

Paul Klee – the Abstract Dimension October 1, 2017 to January 21, 2018

Media release Paul Klee – The Abstract Dimension October 1, 2017 to January 21, 2018 From October 1, 2017, to January 21, 2018, the Fondation Beyeler will be presenting a major exhibition of the work of Paul Klee, one of the most important painters of the twentieth century. The exhibition undertakes the first-ever detailed exploration of Kleeʼs relationship to abstraction, one of the central achievements of modern art. Paul Klee was one of the many European artists who took up the challenge of abstraction. Throughout his oeuvre, from his early beginnings to his late period, we find examples of the renunciation of the figurative and the emergence of abstract pictorial worlds. Nature, architecture, music and written signs are the main recurring themes. The exhibition, comprising 110 works from twelve countries, brings this hitherto neglected aspect of Kleeʼs work into focus. The exhibition is organized as a retrospective, presenting the groups of works that illustrate the main stages in Kleeʼs development as a painter. It begins, in the first of the seven rooms, with Kleeʼs apprenticeship as a painter in Munich in the 1910s, followed by the celebrated journey to Tunisia in 1914, and continues through World War I, and the Bauhaus decade from 1921 to 1931, with the well- known “chessboard” pictures, the layered watercolors, and works that respond to the experiments of the 1930s with geometric abstraction. The next section features a selection of the pictures painted after Kleeʼs travels in Italy and Egypt in the later 1920s and early 1930s. Finally, the exhibition examines the “sign” pictures of Kleeʼs late period, and the prefiguration, in his conception of painting, of developments in the art of the postwar era. -

L'été Giacometti À La Fondation Maeght by Michel Gathier

www.smartymagazine.com L'été Giacometti à la Fondation Maeght by Michel Gathier >> SAINT-PAUL-DE-VENCE Toujours chez Alberto Giacometti revient ce fil incandescent de la sculpture comme si celle-ci, de ses mains, se réconciliait avec son point d'origine, délivrée de sa matière, réduite à la seule vérité du nerf qui l'organise et lui donne vie. Alberto Giacometti est à la fois celui qui parle de l'origine et qui trace un autre chemin. « L'homme qui marche » est pétri de cendre et, tel le chien ou le chat de ses sculptures, il renifle des miettes de lumière pour continuer à vivre. La lumière, ce fut son père Giovanni qui, dans la peinture, la célébra. Né en 1868, il inaugura une lignée familiale d'artistes qui durant plus d'un siècle perpétua cette croyance en l'art, cette volonté folle de découvrir la vérité du monde. La Fondation Maeght nous raconte aujourd'hui cette histoire-là qui est celle du feu et de la cendre, celle des braises qui nourrissent de nouvelles flammes pour croire en la vie. Cette aventure s'incarne dans cette famille qui, dans la peinture, la sculpture, la décoration ou l’architecture, embrassa le monde de sa passion créatrice. Giovanni eut trois fils. Alberto, l'aîné, rayonne encore du bronze de ses sculptures émaciées et son œuvre s'expose aujourd'hui à Saint Paul de Vence comme au Forum Grimaldi de Monaco. Entre l'ombre et la lumière, le plein et le vide, il nous place au cœur de l'acte créateur – celui que Nietzsche évoquait dans « La naissance de la tragédie » : l'opposition fondamentale entre le principe apollinien lié à la lumière et au feu et le principe dionysiaque sous les auspices de l'obscurité et de l'effacement. -

Entre Classicismo E Romantismo. Ensaios De Cultura E Literatura

Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism is an academic series published on- line by the Centre for English, Translation and Anglo-Portuguese Studies (CETAPS) and hosted by the central library of the Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Portugal. Studies in Classicism and Romanticism has come into being as a result of the commitment of a group of scholars who are especially interested in English literature and culture from the mid-seventeenth to the mid- nineteenth century. The principal objective of the series is the publication in electronic format of monographs and collections of essays, either in English or in Portuguese, with no pre-established methodological framework, as well as the publication of relevant primary texts from the period c. 1650–c. 1850. Series Editors Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Editorial 2 Sumário Apresentação 4 Maria Luísa Malato Borralho, “Metamorfoses do Soneto: Do «Classicismo» ao «Romantismo»” 5 Adelaide Meira Serras, “Science as the Enlightened Route to Paradise?” 29 Paula Rama-da-Silva, “Hogarth and the Role of Engraving in Eighteenth-Century London” 41 Patrícia Rodrigues, “The Importance of Study for Women and by Women: Hannah More’s Defence of Female Education as the Path to their Patriotic Contribution” 56 Maria Leonor Machado de Sousa, “Sugestões Portuguesas no Romantismo Inglês” 65 Maria Zulmira Castanheira, “O Papel Mediador da Imprensa Periódica na Divulgação da Cultura Britânica em Portugal ao Tempo do Romantismo (1836-1865): Matérias e Imagens” 76 João Paulo Ascenso P. -

Alberto Giacometti: a Biography Sylvie Felber

Alberto Giacometti: A Biography Sylvie Felber Alberto Giacometti is born on October 10, 1901, in the village of Borgonovo near Stampa, in the valley of Bregaglia, Switzerland. He is the eldest of four children in a family with an artistic background. His mother, Annetta Stampa, comes from a local landed family, and his father, Giovanni Giacometti, is one of the leading exponents of Swiss Post-Impressionist painting. The well-known Swiss painter Cuno Amiet becomes his godfather. In this milieu, Giacometti’s interest in art is nurtured from an early age: in 1915 he completes his first oil painting, in his father’s studio, and just a year later he models portrait busts of his brothers.1 Giacometti soon realizes that he wants to become an artist. In 1919 he leaves his Protestant boarding school in Schiers, near Chur, and moves to Geneva to study fine art. In 1922 he goes to Paris, then the center of the art world, where he studies life drawing, as well as sculpture under Antoine Bourdelle, at the renowned Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He also pays frequent visits to the Louvre to sketch. In 1925 Giacometti has his first exhibition, at the Salon des Tuileries, with two works: a torso and a head of his brother Diego. In the same year, Diego follows his elder brother to Paris. He will model for Alberto for the rest of his life, and from 1929 on also acts as his assistant. In December 1926, Giacometti moves into a new studio at 46, rue Hippolyte-Maindron. The studio is cramped and humble, but he will work there to the last. -

Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 Ó Copyright by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 by Joanna Marie Fiduccia Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor George Thomas Baker, Chair This dissertation presents the first extended analysis of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture between 1935 and 1945. In 1935, Giacometti renounced his abstract Surrealist objects and began producing portrait busts and miniature figures, many no larger than an almond. Although they are conventionally dismissed as symptoms of a personal crisis, these works unfold a series of significant interventions into the conventions of figurative sculpture whose consequences persisted in Giacometti’s iconic postwar work. Those interventions — disrupting the harmonious relationship of surface to interior, the stable scale relations between the work and its viewer, and the unity and integrity of the sculptural body — developed from Giacometti’s Surrealist experiments in which the production of a form paradoxically entailed its aggressive unmaking. By thus bridging Giacometti’s pre- and postwar oeuvres, this decade-long interval merges two ii distinct accounts of twentieth-century sculpture, each of which claims its own version of Giacometti: a Surrealist artist probing sculpture’s ambivalent relationship to the everyday object, and an Existentialist sculptor invested in phenomenological experience. This project theorizes Giacometti’s artistic crisis as the collision of these two models, concentrated in his modest portrait busts and tiny figures. -

Alberto Giacometti a Retrospective Marvellous Reality

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI A RETROSPECTIVE MARVELLOUS REALITY PRESS KIT EXHIBITION 3 July to 29 August 2021 GRIMALDI FORUM MONACO IN COLLABORATION WITH FONDATION GIACOMETTI FONDA TION- GIACOMETTI 1960 © Succession Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti, Paris + Adagp, Paris) Adagp, + Paris Giacometti, (Fondation Alberto Giacometti 1960 © Succession Homme qui marche II, Homme qui marche Alberto Giacometti, Alberto Giacometti, S UMMARY ALBERTO GIACOMETTI, A RETROSPECTIVE. MARVELLOUS REALITY p.5 Foreword by Sylvie Biancheri Managing Director of the Grimaldi Forum Monaco p.6 Curator’s note by Émilie Bouvard Exhibition curator, Director of Collections and Scientific Programme at the Fondation Alberto Giacometti “Verbatim” by Christian Alandete, Artistic Director at the Giacometti Institute p.8 Exhibition trail Note of the scenographer William Chatelain Focus on the immersive space: Giacometti’s studio VERBATIM DE CHRISTIAN ALAN- DETE DIRECTEURp.13 Selection ARTISTIQUE of worksDE L’INS exhibited- TITUT GIACOMETTI p.22 Alberto Giacometti’s Biography p.26 Around the exhibition Exhibition catalogue Children workshops A Giacometti summer on the Côte d’Azur p.30 Complementary visuals for the press p.38 The partners of the exhibition p.40 The Fondation Giacometti p.42 Grimaldi Forum Monaco p.46 To discover also this summer at Grimaldi Forum Exhibition “Jewelry by artists, from Picasso to Koons - The Diane Venet Collection” p.48 Practical information and press contacts MARVELLOUS REALITY MARVELLOUS . LE RÉEL MERVEILLEUX LE RÉEL . F OREWORD SYLVIE BIANCHERI, -

Francis Bacon: Five Decades Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FRANCIS BACON: FIVE DECADES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anthony Bond,Martin Harrison | 240 pages | 15 Jun 2015 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500291955 | English | London, United Kingdom Francis Bacon: Five Decades PDF Book Francis Bacon is probably my all-time favorite painter. The shadow looks like a sculpture of a shadow rather than the absence of light whereas the figure simply dissolves into the field. Leave a Reply Cancel reply Your email address will not be published. Marina might be right, but that is the question about the prices at the art market. He travelled with his new lover Peter Lacey to Tangier. He soon broke his own rules and we witness examples of narrative and depictions of the dead, such as the never before exhibited Seated Figure , showing a profile of Dyer. But can a life self- described as chaos really be reduced to year time slots? If your familiarity with the work has been garnered through jpegs and printed catalogues, then there is a lot to re-learn about the grandeur, detail and materials such as sand, dust and aerosol applied with such tools as textured fabric of these painting up close. For more information about the piece, click here! This generously illustrated monograph opens with the fecund period, then traces subsequent periods of exceptional artistic output, decade by decade, through the end of Bacon's career. Painted between May and June of , this great Baconian landscape was the last work the artist made before a major retrospective of his work held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in Triptych, The triptych is a large three panel painting each panel measuring 78 x 58 in, x The figure itself is hinted at with the use of very little paint and virtually no drawing of forms. -

By Fernando Herrero-Matoses

ANTONIO SAURA'S MONSTRIFICATIONS: THE MONSTROUS BODY, MELANCHOLIA, AND THE MODERN SPANISH TRADITION BY FERNANDO HERRERO-MATOSES DISSERTATION Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Jonathan D. Fineberg, Chair Associate Professor Jordana Mendelson, New York University Assistant Professor Terri Weissman Associate Professor Brett A. Kaplan Associate Professor Elena L. Delgado Abstract This dissertation examines the monstrous body in the works of Antonio Saura Atares (1930-1998) as a means of exploring moments of cultural and political refashioning of the modern Spanish tradition during the second half of the twentieth century. In his work, Saura rendered figures in well-known Spanish paintings by El Greco, Velázquez, Goya and Picasso as monstrous bodies. Saura’s career-long gesture of deforming bodies in discontinuous thematic series across decades (what I called monstrifications) functioned as instances for artistic self-evaluation and cultural commentary. Rather than metaphorical self-portraits, Saura’s monstrous bodies allegorized the artistic and symbolic body of his artistic ancestry as a dismembered and melancholic corpus. In examining Saura’s monstrifications, this dissertation closely examines the reshaping of modern Spanish narrative under three different political periods: Franco’s dictatorship, political transition, and social democracy. By situating Saura’s works and texts within the context of Spanish recent political past, this dissertation aims to open conversations and cultural analyses about the individual interpretations made by artists through their politically informed appropriations of cultural traditions. As I argue, Saura’s monstrous bodies incarnated an allegorical and melancholic gaze upon the fragmentary and discontinuous corpus of Spanish artistic legacy as an always-retrieved yet never restored body. -

Press Release

Press Release extended until 02.02.2011 Pablo Picasso, Woman (from the period of Demoiselles d‘Avignon), 1907 Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Inv. 65.2 © Succession Picasso/VBK, Vienna 2010 PLEASE ADDRESS QUESTIONS TO Mag. Klaus Pokorny Leopold Museum-Private Foundation Press / Public Relations MuseumsQuartier Wien Tel +43.1.525 70-1507 1070 Vienna, Museumsplatz 1 Fax +43.1.525 70-1500 www.leopoldmuseum.org [email protected] Press Release Page 2 CÉZANNE – PICASSO – GIACOMETTI Masterpieces from the Fondation Beyeler 17.09.2010 – 17.01.2011 In its exhibition Cezanne – Picasso – Giacometti, the Leopold Museum is hosting Austria’s first-ever showing of a representative selection of works from the collection of the Beyeler Foundation. Shortly before his surprising death in June of this year, Prof. Dr. Rudolf Leopold (1925–2010) personally selected the works to be shown. The Picasso painting Woman (1907), created during the same period as Demoiselles d’Avignon, is a work that was particularly cherished by Ernst Beyeler—and which will now be seen in Vienna. This painting otherwise never leaves the building in Riehen near Basel which star architect Renzo Piano built to house the Beyeler Collection. Elisabeth Leopold, Patricia Spiegelfeld and Franz Smola are the curators of this exhibition, to open on Friday, 17 September 2010, which will show outstanding works of classical modernism complimented by non-European art. Peter Weinhäupl, Managing Director of the Leopold Museum, also brought architect Markus Spiegelfeld on board to transfer the atmosphere of the Beyeler Collection’s exhibition building into the Atrium of the Leopold Museum by means of a few effective architectural adjustments. -

![Perspective, 3 | 2008, « Xxe-Xxie Siècles/Le Canada » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 15 Août 2013, Consulté Le 01 Octobre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6274/perspective-3-2008-%C2%AB-xxe-xxie-si%C3%A8cles-le-canada-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-15-ao%C3%BBt-2013-consult%C3%A9-le-01-octobre-2020-1856274.webp)

Perspective, 3 | 2008, « Xxe-Xxie Siècles/Le Canada » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 15 Août 2013, Consulté Le 01 Octobre 2020

Perspective Actualité en histoire de l’art 3 | 2008 XXe-XXIe siècles/Le Canada Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/3229 DOI : 10.4000/perspective.3229 ISSN : 2269-7721 Éditeur Institut national d'histoire de l'art Édition imprimée Date de publication : 30 septembre 2008 ISSN : 1777-7852 Référence électronique Perspective, 3 | 2008, « XXe-XXIe siècles/Le Canada » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 15 août 2013, consulté le 01 octobre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/3229 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/perspective.3229 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 1 octobre 2020. 1 xxe-xxie siècles Entretien avec Bill Viola sur l’histoire de l’art ; Giacometti ; l’urbanisme des villes d’Europe centrale ; publications récentes sur la couleur au cinéma et dans la photographie, le postmodernisme, les archives d’art contemporain et les revues d’art. Le Canada Développement et pratiques actuelles de la discipline : de l’histoire de l’art aux études d’intermédialité, le rôle des musées et de la muséographie ; Ancien et Nouveau Mondes ; chroniques sur art et cinéma, les revues, le patrimoine… Perspective, 3 | 2008 2 SOMMAIRE De l’utilité des revues en histoire de l’art Didier Schulmann XXe-XXIe siècles Débat Bill Viola, l’histoire de l’art et le présent du passé Bill Viola Alberto Giacometti aujourd’hui Thierry Dufrêne Travaux L’urbanisme et l’architecture des villes d’Europe centrale pendant la première moitié du XXe siècle Eve Blau Actualité Couleur et cinéma : vers la fin des aveux d’impuissance Pierre Berthomieu L’histoire de la photographie prend des couleurs Kim Timby Autour de Fredric Jameson : le postmodernisme est mort ; vive le postmodernisme ! Annie Claustres Les archives d’art contemporain Victoria H. -

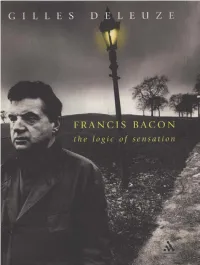

Francis Bacon: the Logic of Sensation

Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation GILLES DELEUZE Translated from the French by Daniel W. Smith continuum LONDON • NEW YORK This work is published with the support of the French Ministry of Culture Centre National du Livre. Liberte • Egalite • Fraternite REPUBLIQUE FRANCAISE This book is supported by the French Ministry for Foreign Affairs, as part of the Burgess programme headed for the French Embassy in London by the Institut Francais du Royaume-Uni. Continuum The Tower Building 370 Lexington Avenue 11 York Road New York, NY London, SE1 7NX 10017-6503 www.continuumbooks.com First published in France, 1981, by Editions de la Difference © Editions du Seuil, 2002, Francis Bacon: Logique de la Sensation This English translation © Continuum 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Gataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library ISBN 0-8264-6647-8 Typeset by BookEns Ltd., Royston, Herts. Printed by MPG Books Ltd., Bodmin, Cornwall Contents Translator's Preface, by Daniel W. Smith vii Preface to the French Edition, by Alain Badiou and Barbara Cassin viii Author's Foreword ix Author's Preface to the English Edition x 1. The Round Area, the Ring 1 The round area and its analogues Distinction between the Figure and the figurative The fact The question of "matters of fact" The three elements of painting: structure, Figure, and contour - Role of the fields 2.