Rio's Post-Olympics Politics Are Less Than Divine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O Culto Dedicado À Marielle Franco: a Luta Pelos Direitos Humanos Na Igreja Da Comunidade Metropolitana Do Rio De Janeiro (ICM) 1

O culto dedicado à Marielle Franco: a luta pelos direitos humanos na Igreja da Comunidade Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro (ICM) 1 Pedro Costa Azevedo (UENF) Introdução Esta comunicação busca compreender de que forma o discurso religioso da Igreja da Comunidade Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro (ICM) mobiliza sua atuação política sob a perspectiva dos direitos humanos. Para isso, este trabalho analisará o culto ecumênico após o assassinato da vereadora Marielle Franco no ano de 2018, onde foi destacada a pauta dos direitos humanos presente em sua trajetória pessoal e política. O pano de fundo desse acontecimento-chave foi marcado pelo apoio de lideranças religiosas pentecostais à campanha de Jair Bolsonaro no pleito eleitoral desse ano. O receio do retrocesso no campo dos direitos humanos, sobretudo quanto aos direitos sexuais e reprodutivos, colocou em disputa os valores e práticas da ICM-Rio em relação à agenda política dos parlamentares e lideranças do campo religioso e político brasileiro. Assim, este trabalho consiste em elucidar as disputas em torno dos valores da atuação religiosa da ICM-Rio em vista das controvérsias no referido contexto político. Em 2018, quando me dirigi ao trabalho de campo, a ICM-Rio encontrava-se2 na Rua do Senado no Centro da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Em uma sala comercial na área térrea do Edifício Liazzi as portas de enrolar3 erguidas indicavam a realização de atividades e cultos dominicais da ICM, que costumavam ocorrer em uma frequência de uma a duas vezes por semana4. Como a instituição fica em uma região central, a acessibilidade aos cultos e atividades torna-se mais viável para pessoas que venham de diferentes bairros e das cidades situadas na região metropolitana, sobretudo, pela proximidade com a Estação Central do Brasil. -

Evangelicals and Political Power in Latin America JOSÉ LUIS PÉREZ GUADALUPE

Evangelicals and Political Power in Latin America in Latin America Power and Political Evangelicals JOSÉ LUIS PÉREZ GUADALUPE We are a political foundation that is active One of the most noticeable changes in Latin America in 18 forums for civic education and regional offices throughout Germany. during recent decades has been the rise of the Evangeli- Around 100 offices abroad oversee cal churches from a minority to a powerful factor. This projects in more than 120 countries. Our José Luis Pérez Guadalupe is a professor applies not only to their cultural and social role but increa- headquarters are split between Sankt and researcher at the Universidad del Pacífico Augustin near Bonn and Berlin. singly also to their involvement in politics. While this Postgraduate School, an advisor to the Konrad Adenauer and his principles Peruvian Episcopal Conference (Conferencia development has been evident to observers for quite a define our guidelines, our duty and our Episcopal Peruana) and Vice-President of the while, it especially caught the world´s attention in 2018 mission. The foundation adopted the Institute of Social-Christian Studies of Peru when an Evangelical pastor, Fabricio Alvarado, won the name of the first German Federal Chan- (Instituto de Estudios Social Cristianos - IESC). cellor in 1964 after it emerged from the He has also been in public office as the Minis- first round of the presidential elections in Costa Rica and Society for Christian Democratic Educa- ter of Interior (2015-2016) and President of the — even more so — when Jair Bolsonaro became Presi- tion, which was founded in 1955. National Penitentiary Institute of Peru (Institu- dent of Brazil relying heavily on his close ties to the coun- to Nacional Penitenciario del Perú) We are committed to peace, freedom and (2011-2014). -

Religious Leaders in Politics

International Journal of Latin American Religions https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-020-00123-1 THEMATIC PAPERS Open Access Religious Leaders in Politics: Rio de Janeiro Under the Mayor-Bishop in the Times of the Pandemic Liderança religiosa na política: Rio de Janeiro do bispo-prefeito nos tempos da pandemia Renata Siuda-Ambroziak1,2 & Joana Bahia2 Received: 21 September 2020 /Accepted: 24 September 2020/ # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The authors discuss the phenomenon of religious and political leadership focusing on Bishop Marcelo Crivella from the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (IURD), the current mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro, in the context of the political involvement of his religious institution and the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the article, selected concepts of leadership are applied in the background of the theories of a religious field, existential security, and the market theory of religion, to analyze the case of the IURD leadership political involvement and bishop/mayor Crivella’s city management before and during the pandemic, in order to show how his office constitutes an important part of the strategies of growth implemented by the IURD charismatic leader Edir Macedo, the founder and the head of this religious institution and, at the same time, Crivella’s uncle. The authors prove how Crivella’s policies mingle the religious and the political according to Macedo’s political alliances at the federal level, in order to strengthen the church and assure its political influence. Keywords Religion . Politics . Leadership . Rio de Janeiro . COVID-19 . Pandemic Palavras-chave Religião . -

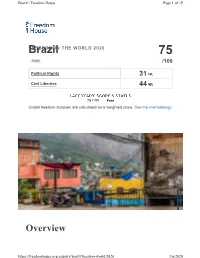

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

Duke University Dissertation Template

‘Christ the Redeemer Turns His Back on Us:’ Urban Black Struggle in Rio’s Baixada Fluminense by Stephanie Reist Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Walter Migolo, Supervisor ___________________________ Esther Gabara ___________________________ Gustavo Furtado ___________________________ John French ___________________________ Catherine Walsh ___________________________ Amanda Flaim Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT ‘Christ the Redeemer Turns His Back on Us:’ Black Urban Struggle in Rio’s Baixada Fluminense By Stephanie Reist Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Walter Mignolo, Supervisor ___________________________ Esther Gabara ___________________________ Gustavo Furtado ___________________________ John French ___________________________ Catherine Walsh ___________________________ Amanda Flaim An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Stephanie Virginia Reist 2018 Abstract “Even Christ the Redeemer has turned his back to us” a young, Black female resident of the Baixada Fluminense told me. The 13 municipalities that make up this suburban periphery of -

O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO Interações: Cultura E Comunidade, Vol

Interações: Cultura e Comunidade ISSN: 1809-8479 [email protected] Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais Brasil Mariano, Ricardo; Schembida de Oliveira, Rômulo Estevan O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO Interações: Cultura e Comunidade, vol. 4, núm. 6, julio-diciembre, 2009, pp. 81-106 Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais Uberlândia Minas Gerais, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=313028473006 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO1 THE SENATOR AND THE BISHOP: MARCELO CRIVELLA AND HIS SHAKESPERIAN DILEMMA Ricardo Mariano(*) Rômulo Estevan Schembida de Oliveira(**) RESUMO Baseado em extensa pesquisa empírica de fontes documentais, o artigo trata da curta trajetória política de Marcelo Crivella, senador do PRB e bispo licenciado da Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus, e de suas aflições e dificuldades eleitorais para tentar dissociar suas posições e atuações como líder neopentecostal e senador, visando diminuir o preconceito, a discriminação e o estigma religiosos dos quais se julga vítima e, especialmente, a forte rejeição eleitoral a suas candidaturas. Discorre sobre os vigorosos e eficientes ataques que ele sofreu durante suas campanhas eleitorais ao Senado em 2002, à prefeitura carioca em 2004, ao governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro em 2006 e novamente à prefeitura em 2008, desferidos por adversários políticos e pelas mídias impressa e eletrônica. -

Political Analysis

POLITICAL ANALYSIS THE CONSEQUENCES OF BRAZILIAN MUNICIPAL ELECTION THE CONSEQUENCES OF than in 2016 (1,035). The PSD won in BRAZILIAN MUNICIPAL ELECTION Belo Horizonte (Alexandre Kalil) and Campo Grande (Marquinhos Trad). The results of the municipal elections showed, in general, that the voter sought candidates more distant from Left reorganization the extremes and with experience in management. For the first time since democratization, PT will not govern any capital in Brazil. In numbers, DEM and PP parties were He lost in Recife and Vitória in the sec- the ones that gained more space, with ond round. The party suffers from de- good performances from PSD, PL, and laying the renewal process and, little by Republicans. The polls also confirmed little, loses its hegemony. In this elec- the loss of prefectures by left-wing par- tion, they saw PSOL win in Belém and ties, especially the PT from former reach the second round in São Paulo. president Lula. PDT and PSB, on the other hand, guar- anteed good spaces in the capitals, es- pecially in the Northeast. Moderation The scenario encourages the reorgani- The municipal election, especially in zation of the left, with the possibility of large urban centers, acclaimed candi- candidates from other parties being the dates who adopted a moderate stance protagonists. It remains to be seen and tried to show themselves prepared whether the PT, which is still the main for the post. Outsiders were not as party in the field, will self-criticize and successful as two years ago, in the las agree to support a name from another general election in Brazil. -

Os Evangélicos Nas Eleições Municipais

Os evangélicos nas eleições municipais André Ricardo Souza1 RESUMO Desde a escolha da Assembléia Constituinte em 1986, os evangélicos, sobretudo pentecostais, vêm tendo presença significativa nas eleições e na vida política nacional. Além de parlamentos, ocuparam relevantes cargos executivos, tais como ministérios, governos estaduais e prefeituras de grandes cidades. Essas conquistas decorrem de iniciativas individuais e arranjos estratégicos de algumas igrejas para otimizar a capacidade de eleger e manter seus representantes. Tal envolvimento vem se dando, muitas vezes, mediante controvérsias e escândalos. As eleições municipais propiciam alcance imediato de poder e também projeção. O presente tra- balho, fruto de pesquisa de pós-doutorado com apoio da FAPESP, aborda esse contexto nacional da participação evangélica na política, enfocando os processos eleitorais de Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo. Palavras-chave: religião e política; igrejas evangélicas; pentecostais e eleições Evangelicals in municipal elections ABSTRACT Since the election of the Constitutional National Assembly in 1986, Evangelicals, mainly the Pentecostals ones have been participating very much in the elections and in the national politics. Beyond parliaments, they have been getting important executive offices like ministries, state 1 ��������������������������� Doutor em Sociologia pela �������������������������������������������������SP e professor adjunto do departamento de socio- logia da �FSCar. Os evangélicos nas eleições municipais 27 governments and big city halls. Those conquests become from indivi- dual initiatives and from some churches strategies in order to elect and maintain their own representatives. This involvement has frequently been taking place among controversies and scandals. This article, result of a post-doctorate research supported by FAPESP deals with the evangelical participation in politics, focusing electoral process in Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. -

The Republic in Crisis and Future Possibilities

DOI: 10.1590/1413-81232017226.02472017 1747 The republic in crisis and future possibilities DEBATE José Maurício Domingues 1 Abstract This text gives a brief reconstruction of the process of impeachment of Brazil’s Presi- dent Dilma Rousseff, which was a ‘coup’ effected through parliament, and situates it at the end of three periods of politics in the Brazilian republic: the first, broader, and democratizing; the second, the age of the PT (Workers’ Party) as the force with the hegemony on the left; and the third, shorter, the cycle of its governments. Together, these phases constitute a crisis of the republic, although not a rupture of the country’s institutional structure, nor a ‘State of Exception’. The paper puts forward three main issues: the developmentalist project implemented by the governments of the PT, in alliance with Brazil’s construction companies; the role of the judiciary, and in particular of ‘Oper- ation Carwash’; and the conflict-beset relation- ship between the new evangelical churches and the LGBT social movements. The essay concludes with an assessment of the defeat and isolation of the left at this moment, and also suggests that democracy, in particular, could be the kernel of a renewed project of the left. Key words Political cycles, Impeachment, Left, democracy, Development 1 Centro de Estudos Estratégicos, Fiocruz. Av. Brasil 4036/10º, Manguinhos. 21040-361 Rio de Janeiro RJ Brasil. [email protected] 1748 Domingues JM Isolation and impeachment her adversary from the PSDB party. Thus, she lost a considerable part of the social base that Brazil is at present immersed in one of the most elected her. -

Religion and Moral Conservatism in Brazilian Politics2

© 2018 Authors. Center for Study of Religion and Religious Tolerance, Belgrade, Serbia.This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License Maria das Dores Campos Machado1 Оригинални научни рад Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro UDC: 27:323(81) Brazil RELIGION AND MORAL CONSERVATISM IN BRAZILIAN POLITICS2 Abstract Brazil has experienced a great deal of political instability and a strengthen- ing of conservatism since the last presidential election and which, during the im- peachment of President Dilma Rousseff, suffered one of its most critical moments. The objective of this communication is to analyse the important role played by religious actors during this process and to demonstrate how the political allianc- es established between Pentecostals and Charismatic Catholics in the National Congress has made possible a series of political initiatives aimed at dismantling the expansion of human rights and policies of the Workers Party governments. With an anti-Communist spirit and a conservative vision of sexual morality and gender relations, these political groups have in recent years approached the so- cial movement Schools without Party (Escola sem partido) and today represent an enormous challenge to Brazilian democracy. Keywords: religion, Brazil, politics, Charismatic Catholics, Evangelicals Introduction Since the 2014 presidential election Brazil has witnessed a period of great political instability and the strengthening of conservative social movements; one of the most critical moments was during the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff. The impeachment petition was filed in the Chamber of Deputies by Pentecostal parliamentarian Eduardo Cunha, who at the time was president of the Chamber, and accepted on 2nd December 2015. -

A Construção Da Imagem De Marcelo Crivella Nas Páginas Do Jornal O Globo Durante As Eleições Municipais De 2008

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO JORNALISMO A CONSTRUÇÃO DA IMAGEM DE MARCELO CRIVELLA NAS PÁGINAS DO JORNAL O GLOBO DURANTE AS ELEIÇÕES MUNICIPAIS DE 2008 Monografia submetida à Banca de Graduação Como requisito para obtenção do diploma de Comunicação Social – Jornalismo JOÃO NOÉ ALVES DE CARVALHO Orientador: Prof. Dr. Mohammed El Hajji Rio de Janeiro 2008 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO A Comissão Examinadora, abaixo assinada, avalia a Monografia A construção da imagem de Marcelo Crivella nas páginas do jornal O Globo durante as eleições municipais de 2008 , elaborada por João Noé Alves de Carvalho. Monografia examinada: Rio de Janeiro, no dia ...../...../..... Comissão Examinadora: Orientador: Prof. Dr. Mohammed El Hajji Doutor em Comunicação pela Escola de Comunicação – UFRJ Departamento de Comunicação - UFRJ Professor Marcelo Helvécio Navarro Serpa Mestre em Comunicação pela Escola de Comunicação – UFRJ Departamento de Comunicação – UFRJ Professor Maurício Durão Schleder Professor Auxiliar da Escola de Comunicação – UFRJ Departamento de Comunicação – UFRJ Rio de Janeiro 2008 CARVALHO, João Noé Alves de. A construção da imagem de Marcelo Crivella nas páginas do jornal O Globo durante as eleições municipais de 2008. Orientador: Mohammed El Hajji. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ/ECO. Monografia em Jornalismo RESUMO O estudo verifica o conteúdo das matérias publicadas pelo jornal O Globo sobre a campanha de Marcelo Crivella para a Prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro nas eleições de 2008. Para isso, utiliza-se de técnicas de análise de discurso que permitam decifrar as vozes atuantes nos textos, títulos e subtítulos de cada reportagem. -

Brazil 2017 International Religious Freedom Report

BRAZIL 2017 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution states freedom of conscience and belief is inviolable, and free exercise of religious beliefs is guaranteed. The constitution prohibits federal, state, and local governments from either supporting or hindering any specific religion. In September the Supreme Court ruled in favor of authorizing confessional religious education in public schools. Also in September the minister of human rights commissioned the special secretary for the promotion of racial equality to investigate the increase in acts of violence and destruction against Afro-Brazilian temples known as terreiros. In a September meeting with a representative from the Ministry of Human Rights, the representative stated that the ministry was prioritizing the creation of committees for the respect of religious diversity in every state, their purpose being to co-draft a national plan on respect for religious diversity. Numerous government officials received civil society training on religious tolerance; one Rio de Janeiro-based nongovernmental organization (NGO) trained 1,500 public officials and students. In July the press reported that members of an alleged street vendor mafia in Rio de Janeiro attacked a Syrian refugee in a religiously motivated physical assault. In August and September unknown perpetrators committed acts of arson, vandalism, and destruction of sacred objects against seven terreiros in Nova Iguacu on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. Eight similar incidents occurred in Sao Paulo in September. The press reported Rio de Janeiro Secretary of Human Rights Atila Alexandre Nunes as stating that many citizens accused evangelical Christian drug traffickers of targeting terreiros for attacks. A representative of the NGO Center for Promotion of Religious Freedom (CEPLIR) said many of the individuals involved in attacks on Afro-Brazilian religious sites and adherents self-declared as evangelicals.