Religion and Moral Conservatism in Brazilian Politics2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Election for Federal Deputy in 2014 - a New Camera, a New Country1

Chief Editor: Fauze Najib Mattar | Evaluation System: Triple Blind Review Published by: ABEP - Brazilian Association of Research Companies Languages: Portuguese and English | ISSN: 2317-0123 (online) Election for federal deputy in 2014 - A new camera, a new country1 A eleição para deputados em 2014 - Uma nova câmara, um novo país Maurício Tadeu Garcia IBOPE Inteligência, Recife, PE, Brazil ABSTRACT In 2014 were selected representatives from 28 different parties in the House of Submission: 16 May 2016 Representatives. We never had a composition as heterogeneous partisan. Approval: 30 May 2016 However, there is consensus that they have never been so conservative in political and social aspects, are very homogeneous. Who elected these deputies? Maurício Tadeu Garcia The goal is to seek a given unprecedented: the profile of voters in each group of Post-Graduate in Political and deputies in the states, searching for differences and socio demographic Electoral Marketing ECA-USP and similarities. the Fundação Escola de Sociologia e Política de São Paulo (FESPSP). KEYWORDS: Elections; Chamber of deputies; Political parties. Worked at IBOPE between 1991 and 2009, where he returned in 2013. Regional Director of IBOPE RESUMO Inteligência. (CEP 50610-070 – Recife, PE, Em 2014 elegemos representantes de 28 partidos diferentes para a Câmara dos Brazil). Deputados. Nunca tivemos na Câmara uma composição tão heterogênea E-mail: partidariamente. Por outro lado, há consenso de que eles nunca foram tão mauricio.garcia@ibopeinteligencia conservadores em aspectos políticos e sociais, nesse outro aspecto, são muito .com homogêneos. Quem elegeu esses deputados? O objetivo deste estudo é buscar Address: IBOPE Inteligência - Rua um dado inédito: o perfil dos eleitores de cada grupo de deputados nos estados, Demócrito de Souza Filho, 335, procurando diferenças e similaridades sociodemográficas entre eles. -

Inteiro Teor Foi Sentido De Que Essa Reforma Política Precisa Sair, E Gravado, Passando O Arquivo De Áudio Corresponden- Muitos Cobram Pressa

REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL DIÁRIO DA CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS ANO LXVI - Nº 091 - SÁBADO, 28 DE MAIO DE 2011 - BRASÍLIA-DF MESA DA CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS (Biênio 2011/2012) PRESIDENTE MARCO MAIA – PT-RS 1ª VICE-PRESIDENTE ROSE DE FREITAS – PMDB-ES 2º VICE-PRESIDENTE EDUARDO DA FONTE – PP-PE 1º SECRETÁRIO EDUARDO GOMES – PSDB-TO 2º SECRETÁRIO JORGE TADEU MUDALEN – DEM-SP 3º SECRETÁRIO INOCÊNCIO OLIVEIRA – PR-PE 4º SECRETÁRIO JÚLIO DELGADO – PSB-MG 1º SUPLENTE GERALDO RESENDE – PMDB-MS 2º SUPLENTE MANATO – PDT-ES 3º SUPLENTE CARLOS EDUARDO CADOCA – PSC-PE 4º SUPLENTE SÉRGIO MORAES – PTB-RS CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS SUMÁRIO SEÇÃO I 1 – ATA DA 130ª SESSÃO DA CÂMARA Consular, Militar, Administrativo e Técnico. celebrado DOS DEPUTADOS, ORDINÁRIA, DA 1ª SESSÃO em Brasília, em 4 de agosto de 2010. ................... 26861 LEGISLATIVA ORDINÁRIA, DA 54ª LEGISLATU- Nº 156/2011 – do Poder Executivo – Subme- RA, EM 27 DE MAIO DE 2011. te à apreciação do Congresso Nacional o texto do * Inexistência de quorum regimental para Acordo entre o Governo da República Federativa abertura da sessão do Brasil e o Governo da República do Mali sobre I – Abertura da sessão o Exercício de Atividade Remunerada por Parte II – Leitura e assinatura da ata da sessão de Dependentes do Pessoal Diplomático, Consu- anterior lar, Militar, Administrativo e Técnico, celebrado em III – Leitura do expediente Bamaco, em 22 de outubro de 2009...................... 26863 Nº 157/2011 – do Poder Executivo – Subme- MENSAGENS te à apreciação do Congresso Nacional o texto do Nº 152/2011 – do -

Religious Leaders in Politics

International Journal of Latin American Religions https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-020-00123-1 THEMATIC PAPERS Open Access Religious Leaders in Politics: Rio de Janeiro Under the Mayor-Bishop in the Times of the Pandemic Liderança religiosa na política: Rio de Janeiro do bispo-prefeito nos tempos da pandemia Renata Siuda-Ambroziak1,2 & Joana Bahia2 Received: 21 September 2020 /Accepted: 24 September 2020/ # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The authors discuss the phenomenon of religious and political leadership focusing on Bishop Marcelo Crivella from the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (IURD), the current mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro, in the context of the political involvement of his religious institution and the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the article, selected concepts of leadership are applied in the background of the theories of a religious field, existential security, and the market theory of religion, to analyze the case of the IURD leadership political involvement and bishop/mayor Crivella’s city management before and during the pandemic, in order to show how his office constitutes an important part of the strategies of growth implemented by the IURD charismatic leader Edir Macedo, the founder and the head of this religious institution and, at the same time, Crivella’s uncle. The authors prove how Crivella’s policies mingle the religious and the political according to Macedo’s political alliances at the federal level, in order to strengthen the church and assure its political influence. Keywords Religion . Politics . Leadership . Rio de Janeiro . COVID-19 . Pandemic Palavras-chave Religião . -

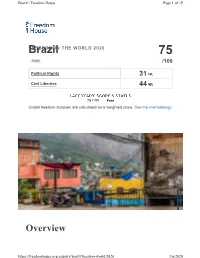

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

6 Confronting Backlash Against Women's Rights And

CONFRONTING BACKLASH AGAINST WOMEN’S RIGHTS AND GENDER 1 EQUALITY IN BRAZIL: A LITERATURE REVIEW AND PROPOSAL Cecilia M. B. Sardenberg 2 Maíra Kubik Mano 3 Teresa Sacchet 4 ABSTRACT: This work is part of a research and intervention programme to investigate, confront and reverse the backlash against gender equality and women’s rights in Brazil, which will be part of the Institute of Development Studies – IDS Countering Backlash Programme, supported by the Swedish International Development Agency - SIDA. This Programme was elaborated in response to the backlash against women's rights and gender equality that has emerged as a growing trend, championed by conservative and authoritarian movements gaining space across the globe, particularly during the last decade. In Brazil, this backlash has been identified as part of an ‘anti-gender’ wave, which has spread considerably since the 2014 presidential elections. Significant changes in Brazil have not only echoed strongly on issues regarding women’s rights and gender justice, but also brought disputes over gender and sexuality to the political arena. To better address the issues at hand in this work, we will contextualize them in their historical background. We will begin with a recapitulation of the re-democratization process, in the 1980s, when feminist and women’s movements emerged as a political force demanding to be heard. We will then look at the gains made during what we here term “the progressive decades for human and women’s rights”, focusing, in particular, on those regarding the confrontation of Gender Based Violence (GBV) in Brazil, which stands as one of the major problems faced by women and LGBTTQIs, aggravated in the current moment of Covid-19 pandemic. -

O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO Interações: Cultura E Comunidade, Vol

Interações: Cultura e Comunidade ISSN: 1809-8479 [email protected] Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais Brasil Mariano, Ricardo; Schembida de Oliveira, Rômulo Estevan O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO Interações: Cultura e Comunidade, vol. 4, núm. 6, julio-diciembre, 2009, pp. 81-106 Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais Uberlândia Minas Gerais, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=313028473006 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO O SENADOR E O BISPO: MARCELO CRIVELLA E SEU DILEMA SHAKESPEARIANO1 THE SENATOR AND THE BISHOP: MARCELO CRIVELLA AND HIS SHAKESPERIAN DILEMMA Ricardo Mariano(*) Rômulo Estevan Schembida de Oliveira(**) RESUMO Baseado em extensa pesquisa empírica de fontes documentais, o artigo trata da curta trajetória política de Marcelo Crivella, senador do PRB e bispo licenciado da Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus, e de suas aflições e dificuldades eleitorais para tentar dissociar suas posições e atuações como líder neopentecostal e senador, visando diminuir o preconceito, a discriminação e o estigma religiosos dos quais se julga vítima e, especialmente, a forte rejeição eleitoral a suas candidaturas. Discorre sobre os vigorosos e eficientes ataques que ele sofreu durante suas campanhas eleitorais ao Senado em 2002, à prefeitura carioca em 2004, ao governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro em 2006 e novamente à prefeitura em 2008, desferidos por adversários políticos e pelas mídias impressa e eletrônica. -

The Conditional Effect of Pork

SUMÁRIO APRESENTAÇÃO DOSSIÊ PODER LEGISLATIVO: NOVOS OLHARES ANTONIO TEIXEIRA DE BARROS MANOEL LEONARDO SANTOS STATUS QUO CHARACTERISTICS OR PRIVATE SECTOR AFFINITY? EXPLAINING PREFERENCES FOR SAFETY NETS IN LATIN AMERICAN LEGISLATURES JOÃO VICTOR GUEDES-NETO 26.2 ASBEL BOHIGUES APOIO ELEITORAL E CONFIANÇA PARLAMENTAR NOS GRUPOS EMPRESARIAIS NO BRASIL LUCAS HENRIQUE RIBEIRO PARLAMENTO E INOVAÇÕES PARTICIPATIVAS: POTENCIALIDADES E LIMITES PARA A INCLU- SÃO POLÍTICA THALES TORRES QUINTÃO CLÁUDIA FERES FARIA Teoria Sociedade ESTRANHAS NO NINHO: UMA ANÁLISE COMPARATIVA DA ATUAÇÃO PARLAMENTAR DE HOMENS E MULHERES NA CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS DANUSA MARQUES BRUNO LIMA E ISSN: 1518-4471 SI LA FIESTA ES TAN ABURRIDA, ¿POR QUÉ TODOS SE QUIEREN QUEDAR? AMBICIÓN PO- LÍTICA Y CARRERAS LEGISLATIVAS EN EL CONGRESO CHILENO (1989-2013) VALENTINA CONEJEROS PINTO PATRICIO NAVIA AS ASSESSORIAS DE MÍDIAS DIGITAIS DOS PARLAMENTARES BRASILEIROS: ORGANIZAÇÃO E PROFISSIONALIZAÇÃO NA CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS MÁRCIO CUNHA CARLOMAGNO SÉRGIO BRAGA Poder Legislativo: RETÓRICAS DO CONSERVADORISMO RELIGIOSO: DISCURSOS PARLAMENTARES CONTRÁRIOS AO USO DO NOME SOCIAL NA ADMINISTRAÇÃO PÚBLICA FEDERAL CIBELE CHERON novos olhares MAURICIO MOYA RELIGIÃO E POLÍTICA NO PARLAMENTO BRASILEIRO: O DEBATE SOBRE DIREITOS HUMANOS NA CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS ANTONIO TEIXEIRA DE BARROS Revista dos Departamentos de CRISTIANE BRUM BERNARDES JÚLIO ROBERTO DE SOUZA PINTO Antropologia e Arqueologia, Ciência Política e THE CONDITIONAL EFFECT OF PORK: THE STRATEGIC USE OF BUDGET ALLOCATION TO BUILD GOVERNMENT -

Terceirização – Confira O Voto De Cada Deputado

Terceirização – Confira o voto de cada deputado Partido/Parlamentar UF Voto DEM Alexandre Leite SP Sim Carlos Melles MG Sim Claudio Cajado BA Sim Eli Côrrea Filho SP Sim Elmar Nascimento BA Não Hélio Leite PA Sim Jorge Tadeu Mudalen SP Sim José Carlos Aleluia BA Sim Mandetta MS Não Marcelo Aguiar SP Sim Mendonça Filho PE Sim Moroni Torgan CE Não Onyx Lorenzoni RS Sim Osmar Bertoldi PR Sim Paulo Azi BA Sim Professora Dorinha Seabra Rezende TO Não Total DEM – 16 PCdoB Alice Portugal BA Não Aliel Machado PR Não Carlos Eduardo Cadoca PE Não Daniel Almeida BA Não Davidson Magalhães BA Não Jandira Feghali RJ Não Jô Moraes MG Não João Derly RS Não Luciana Santos PE Não Orlando Silva SP Não Rubens Pereira Júnior MA Não Wadson Ribeiro MG Não Total PCdoB – 12 PDT Abel Mesquita Jr. RR Não Afonso Motta RS Não André Figueiredo CE Não Dagoberto MS Não Damião Feliciano PB Não Félix Mendonça Júnior BA Sim Flávia Morais GO Não Giovani Cherini RS Não Major Olimpio SP Não Marcelo Matos RJ Não Marcos Rogério RO Não Mário Heringer MG Sim Pompeo de Mattos RS Não Roberto Góes AP Não Ronaldo Lessa AL Não Sergio Vidigal ES Não Subtenente Gonzaga MG Não Weverton Rocha MA Não Wolney Queiroz PE Não Total PDT – 19 PEN André Fufuca MA Sim Junior Marreca MA Não Total PEN – 2 PHS Adail Carneiro CE Não Diego Garcia PR Não Kaio Maniçoba PE Sim Marcelo Aro MG Sim Total PHS – 4 PMDB Alberto Filho MA Sim Aníbal Gomes CE Sim Baleia Rossi SP Sim Cabuçu Borges AP Sim Carlos Bezerra MT Sim Carlos Henrique Gaguim TO Sim Carlos Marun MS Sim Celso Jacob RJ Sim Celso Maldaner SC Sim Celso Pansera RJ Sim Daniel Vilela GO Sim Danilo Forte CE Sim Darcísio Perondi RS Sim Dulce Miranda TO Não Edinho Bez SC Sim Edio Lopes RR Sim Eduardo Cunha RJ Art. -

Brazil 2017 Human Rights Report

BRAZIL 2017 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Brazil is a constitutional, multiparty republic. In 2014 voters re-elected Dilma Rousseff as president in elections widely considered free and fair. In August 2016 Rousseff was impeached, and the vice president, Michel Temer, assumed the presidency as required by the constitution. Civilian authorities at times did not maintain effective control over security forces. The most significant human rights issues included arbitrary deprivation of life and other unlawful killings; poor and sometimes life-threatening prison conditions; violence against and harassment of journalists and other communicators; official corruption at the highest levels of government; societal violence against indigenous populations; societal violence against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex persons; killings of human rights defenders; and forced labor. The government prosecuted officials who committed abuses; however, impunity and a lack of accountability for security forces was a problem, and an inefficient judicial process delayed justice for perpetrators as well as victims. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary Deprivation of Life and Other Unlawful or Politically Motivated Killings There were no reports the federal government or its agents committed politically motivated killings, but unlawful killings by state police were reported. In some cases police employed indiscriminate force. The extent of the problem was difficult to determine, since comprehensive, reliable statistics on unlawful police killings were not available. Official statistics showed police killed numerous civilians but did not specify which cases may have been unlawful. For instance, the Rio de Janeiro Public Security Institute, a state government entity, reported that from January to June, police killed 581 civilians in “acts of resistance” (similar to resisting arrest) in Rio de Janeiro State. -

Dossie Doi: Doi: Doi

DOSSIE DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/nep.v3i3 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/nep.v3i2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/nep.v3i2 PROSOPOGRAFIA FAMILIAR DA OPERAÇÃO "LAVA-JATO" E DO MINISTÉRIO TEMER1 Ricardo Costa de Oliveira2 José Marciano Monteiro3 Mônica Helena Harrich Silva Goulart4 Ana Crhistina Vanali5 RESUMO: os autores apresentam a prosopografia dos principais operadores da "Lava-Jato" e a composição social, política e familiar do primeiro Ministério do Governo de Michel Temer. Analisou-se as relações familiares, as conexões entre estruturas de poder político, partidos políticos e estruturas de parentesco, formas de nepotismo, a reprodução familiar dos principais atores. Pesquisou-se a lógica familiar, as genealogias, as práticas sociais, políticas e o ethos familiar dentro das instituições políticas para entender de que maneira as origens sociais e familiares dos atores burocráticos, jurídicos e políticos formam um certo "habitus de classe", certa mentalidade política, uma cultura administrativa, uma visão social de mundo, padrões de carreiras e de atuações políticas relativamente homogêneos. As origens sociais, a formação escolar, acadêmica, as práticas profissionais, os cargos estatais, os privilégios e os estilos de vida, as ideologias e os valores políticos apresentam muitos elementos em comum nas biografias, e nas trajetórias sociais e políticas desses atores. Palavras-chave: Lava-Jato. Ministério Temer. Prosopografia. FAMILY PROSOPHOGRAPHY OF THE "LAVA-JATO" OPERATION AND THE MINISTRY TEMER ABSTRACT: The authors present the prosopography of the main operators of the "Lava-Jet" and the social, political and family composition of the first Ministry of Government of Michel Temer. Family relations, the connections between structures of political power, political parties and kinship structures, forms of nepotism, and family reproduction of the main actors were analyzed. -

Os Evangélicos Nas Eleições Municipais

Os evangélicos nas eleições municipais André Ricardo Souza1 RESUMO Desde a escolha da Assembléia Constituinte em 1986, os evangélicos, sobretudo pentecostais, vêm tendo presença significativa nas eleições e na vida política nacional. Além de parlamentos, ocuparam relevantes cargos executivos, tais como ministérios, governos estaduais e prefeituras de grandes cidades. Essas conquistas decorrem de iniciativas individuais e arranjos estratégicos de algumas igrejas para otimizar a capacidade de eleger e manter seus representantes. Tal envolvimento vem se dando, muitas vezes, mediante controvérsias e escândalos. As eleições municipais propiciam alcance imediato de poder e também projeção. O presente tra- balho, fruto de pesquisa de pós-doutorado com apoio da FAPESP, aborda esse contexto nacional da participação evangélica na política, enfocando os processos eleitorais de Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo. Palavras-chave: religião e política; igrejas evangélicas; pentecostais e eleições Evangelicals in municipal elections ABSTRACT Since the election of the Constitutional National Assembly in 1986, Evangelicals, mainly the Pentecostals ones have been participating very much in the elections and in the national politics. Beyond parliaments, they have been getting important executive offices like ministries, state 1 ��������������������������� Doutor em Sociologia pela �������������������������������������������������SP e professor adjunto do departamento de socio- logia da �FSCar. Os evangélicos nas eleições municipais 27 governments and big city halls. Those conquests become from indivi- dual initiatives and from some churches strategies in order to elect and maintain their own representatives. This involvement has frequently been taking place among controversies and scandals. This article, result of a post-doctorate research supported by FAPESP deals with the evangelical participation in politics, focusing electoral process in Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. -

Sessões Do Plenário

SESSÕES DO PLENÁRIO 54 ª Sessão Ordinária da Assembleia Legislativa do Estado da Bahia, 1º de junho de 2016. PRESIDENTE: DEPUTADO JOSÉ DE ARIMATÉIA (AD HOC) À hora regimental, na lista de presença, verificou-se o comparecimento dos senhores Deputados: Aderbal Caldas, Adolfo Menezes, Adolfo Viana, Alan Castro, Alan Sanches, Alex da Piatã, Alex Lima, Ângela Sousa, Ângelo Coronel, Antônio Henrique Júnior, Augusto Castro, Bira Corôa, Bobô, Carlos Geilson, Carlos Ubaldino, David Rios, Eduardo Salles, Euclides Fernandes, Fábio Souto, Fabíola Mansur, Fabrício Falcão, Fátima Nunes, Gika, Herzem Gusmão, Hildécio Meireles, Ivana Bastos, Jânio Natal, José de Arimatéia, Joseildo Ramos, Jurandy Oliveira, Leur Lomanto Júnior, Luciano Ribeiro, Luciano Simões Filho, Luiz Augusto, Luiza Maia, Manassés, Marcelino Galo, Marcell Moraes, Marcelo Nilo, Maria del Carmen, Marquinho Viana, Nelson Leal, Neusa Cadore, Pablo Barrozo, Pastor Sargento Isidório, Paulo Câmera, Paulo Rangel, Pedro Tavares, Reinaldo Braga, Robério Oliveira, Roberto Carlos, Robinho, Rogério Andrade, Rosemberg Pinto, Sandro Régis, Sidelvan Nóbrega, Soldado Prisco, Targino Machado, Tom Araújo, Vando, Zé Neto, Zé Raimundo e Zó.(63) O Sr. PRESIDENTE (José de Arimatéia):- Invocando a proteção de Deus, em nome da comunidade, declaro aberta a presente sessão. PEQUENO EXPEDIENTE O Sr. PRESIDENTE (José de Arimatéia):- Leitura do Expediente. OFÍCIO Do Deputado Paulo Câmera comunicando que, devido a compromissos assumidos no cumprimento do mandato parlamentar, esteve ausente nas Sessões dos dias 17, 18 e 19/05/2016. 1 O Sr. PRESIDENTE (José de Arimatéia):- Submeto ao Plenário as seguintes atas: sessões ordinárias: 34ª, 45ª, 46ª, 48ª ocorridas, respectivamente, nos dias 19 e 12 de abril, 16 e18 de maio; 16ª especial do dia 28 de abril de 2016; especiais 18ª, 19ª, 26ª dos dias 5, 9, 20 de maio de 2016.