1 Perhaps That's Just the Way It Is the Square Knot Is a Binding Knot Used

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Thesis Entitled Knotted Numbers, Mnemonics, and Narratives: Khipu

A Thesis entitled Knotted Numbers, Mnemonics, and Narratives: Khipu Scholarship and the Search for the “Khipu Code” throughout the Twentieth and Twenty First Century by Veronica Lysaght Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in History ________________________________________ Charles Beatty-Medina, Committee Chair ________________________________________ Roberto Padilla, Committee Member ________________________________________ Kim Nielsen, Committee Member _______________________________________ Amanda Bryant-Friedrich, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo July 2016 Copyright 2016, Veronica Lee Lysaght This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of Knotted Numbers, Mnemonics, and Narratives: Khipu Scholarship and the Search for the “Khipu Code” throughout the Twentieth and Twenty First Century by Veronica Lysaght Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in History The University of Toledo July 2016 My thesis explores the works of European and North American khipu scholars (mainly anthropologists) from 1912 until 2010. I analyze how they incorporated aspects of their own culture and values into their interpretations of Inca khipus’ structure and functions. As Incas did not leave behind a written language or even clear non-written descriptions of their khipus, anthropologists interpreted khipus’ purposes with a limited base of Inca perspectives. Thus, every work of khipu literature that I study reflects both elements of Inca culture and the author’s own cultural perspectives as a twentieth or twenty-first century academic. I show how each work is indicative of modern cultural views on writing, as well as academic movements and broader social trends that were prominent during the author’s time. -

Chinese Knotting

Chinese Knotting Standards/Benchmarks: Compare and contrast visual forms of expression found throughout different regions and cultures of the world. Discuss the role and function of art objects (e.g., furniture, tableware, jewelry and pottery) within cultures. Analyze and demonstrate the stylistic characteristics of culturally representative artworks. Connect a variety of contemporary art forms, media and styles to their cultural, historical and social origins. Describe ways in which language, stories, folktales, music and artistic creations serve as expressions of culture and influence the behavior of people living in a particular culture. Rationale: I teach a small group self-contained Emotionally Disturbed class. This class has 9- 12 grade students. This lesson could easily be used with a larger group or with lower grade levels. I would teach this lesson to expose my students to a part of Chinese culture. I want my students to learn about art forms they may have never learned about before. Also, I want them to have an appreciation for the work that goes into making objects and to realize that art can become something functional and sellable. Teacher Materials Needed: Pictures and/or examples of objects that contain Chinese knots. Copies of Origin and History of knotting for each student. Instructions for each student on how to do each knot. Cord ( ½ centimeter thick, not too rigid or pliable, cotton or hemp) in varying colors. Beads, pendants and other trinkets to decorate knots. Tweezers to help pull cord through cramped knots. Cardboard or corkboard piece for each student to help lay out knot patterns. Scissors Push pins to anchor cord onto the cardboard/corkboard. -

The Quipu of the Incas: Its Place in the History of Communication by Leo J

The Quipu of the Incas: Its Place in the History of Communication by Leo J. Harris The study of postal history has, through time, been defined in a number of different ways. Most of us consider postal history to be the study of how a paper with writing on it was carried in some sort of organized fashion from place to place. But more broadly, and for the purpose of this short article, postal history could be defined as the study of moving information on an organized basis from one place to another. This definition has particular meaning when one considers the situation in which the prevailing language had no written form. That is precisely the case with the Inca Empire in South America. The Inca Empire (circa 1400 AD to 1532 AD) stretched from Chile and Argentina on the south, through Bolivia and Peru, to Ecuador on the north. The topography was desert, the high Andes mountains, plateaus and jungles. The empire was held together by two principal means. The first was a highly developed, often paved road system, which even today is followed in part by the Pan American highway. The second were “Chasquis,” Indian runners who carried messages from one Tambo (or way-station) to another, over these roads. In this manner adequate communication was assured, but to this had to be added a method to preserve and transmit information. Given the length and breadth of the Empire, the Inca hierarchy needed a significant and continuing flow of information and data to exercise economic and political control over greatly diverse inhabitants. -

Knotting Matters 5

‘KNOTTING MATTERS’ THE QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER OF THE INTERNATIONAL GUILD OF KNOT TYERS President: Percy W. Blandford Hon. Secretary & Editor, Geoffrey BUDWORTH, 45, Stambourne Way, Upper Norwood, London S.E.19 2PY, England. tel: 01-6538757 Issue No. 5 October, 1983 - - - oOo - - - EDITORIAL In an article within this issue Dr. Harry ASHER describes an original method of classifying knots. There will be those - understandably - who dismiss his ideas because they may seem impractical. After all, didn’t Australian knot craftsman Charles H.S. THOMASON write recently in these pages; “I don’t know the names of many of the knots I tie.” One of the Guild’s aims is, however, to undertake research into all aspects of knotting. When I had to produce a training manual entitled ‘The Identification of Knots’ for forensic scientists and other criminal investigators, my first challenge was to devise a system of grouping and classifying over 100 basic knots, bends and hitches. You can’t ask people who don’t know knot names to look one up in an alphabetical index. I chose to group them according to the number of crossing points each one possessed. Scientists can count. Harry ASHER’s method actually describes in a kind of speed-writing how they are tied. Mathematicians studying topology assign numerical values to knots and then evolve formulae to compare them. The “Reidemeister Moves” are, I believe, an attempt to give names to the ways in which a cord may be arranged and rearranged. Some of us will never acquire the mathematical language to understand all of this; but we surely must be able to treat knots systematically and logically if we are to learn more about them than we know already. -

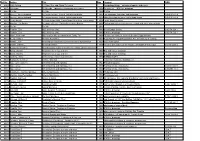

Ref No Author Title Date Content ISBN 99409 33 Rope Ties and Chain

Ref No Author Title Date Content ISBN 99409 Hull, Burling 33 Rope Ties and Chain Releases Escapology/Magic - authorised update and reprint 99310 Unknown 70 Noeuds - epissures et amarrages de marine 1958 French text B/W line drawings 99481 Ref No Ref No 2006 Ref No 99398 Harvey, James Edward A Comprehensive Text of Turk's Head Knots 1997 Line drawings, formulae and diagrams 0-9587026-2-4 99403 Harvey, James Edward A Comprehensive Text of Turk's Head Knots 1997 Many formulae for tying Turk's Head Knots 0-9587026-2-4 99454 Scott, Harold A Guide to the Multi, SingleStrand Cruciform Turk's Head 2001 Turk's Head Crosses 99425 Morales, Lily Qualls A Labour of Love - Tatting Beyond the Basics 2002 Tatting instructions and patterns - black and white photographs 99489 Ref No Ref No 2012 99224 Franklin, Eric ABC of Knots (An) 1982 Scout Badge Series 0 85174 364 1 99281 Franklin, Eric ABC of Knots (An) 1986 B/W line drawings 0 85174 526 1 99375 Wolfe, Robert M. ABC's of Double Overhand Knot Tying, The 1996 Treatise on Ashley's, Hunter's Bend & Zeppelin Knot 99201 Kemp, Barry J Amarno Reports V 1989 Report by the Egypt Exploration Soc on basketry & cordage 99181 Halifax, John Amazing Universal Knot & the Distinctive Norfolk Knot 1990 loose leaf, typed 99406 Meikle, Jeffrey L. American Plastic 1995 Includes discussion on the naming of NYLON (Photocopy) 0-8135-2234-x 99410 Budworth, Geoffrey An intreaguing folder of Geoffrey's cuttings, photos and notes 99110 Barns, Stanley Anglers knots in gut and line 1951 B/w and colour drawings 99225 Barns, Stanley Anglers knots in gut and line 1951 B/w and colour drawings 99226 Hankey, Henry Archaeology: Artifacts & Artifiction 1985 SIGNED COPY 99370 Budworth, Geoffrey Archive Material Collection of photos, clippings etc. -

Knotting Matters 92

GUILD SUPPLIES BOOKS Geoffrey Budworth The Knot Book £4.99 Plaited Moebius Bends £2.50* Knotlore 2 - a miscellany of quotes from fact and fiction £2.50* Knot Rhymes and Reasons £1.50* The Knot Scene £2.00* Brian Field Breastplate Designs £3.50* Concerning Crosses £2.00* Eric Franklin Turksheads the Traditional Way £1.50* Nylon Novelties £2.00* Stuart Grainger Knotcraft £4.00* Ropefolk £1.30* Creative Ropecraft (Hardback - 3rd Ed.) £9.95 Knotted Fabrics (Hardback) £9.00 Colin Jones The DIY Book of Fenders £9.95 Harold Scott A Guide to the Multi, Single-Strand Cruciform Turk’s Head £4.00* Skip Pennock Decorative Woven Flat Knots £12.50* * Bulk purchases of these items are available at a discount - phone for details Supplies Secretary: Bruce Turley 19 Windmill Avenue, Rubery, Birmingham B45 9SP email: [email protected] Telephone: 0121 453 4124 Knot Charts Full set of 100 charts - £10.00 Individual charts - £0.20 Knotting Matters Guild Tie Some past editions available Long, dark blue with Guild logo Brian Field - contact the Secretary for in gold - £8.95 Breastplate Designs £3.50* details Concerning Crosses £2.00* Rubber Stamp IGKT Member, with logo Badges - all with Guild logo (excludes stamp pad) £4.00 Blazer Badge - £1.00 Enamel Brooch - £2.00 Windscreen Sticker - £1.00 Certificate of Membership Parchment membership scroll, signed by the President and Hon. Sec., for mounting or hanging - £2.50 Cheques payable to IGKT, or simply send your credit card details PS Don’t forget to allow for postage 2 Knotting Matters june 2006 3 Knotting Matters The Magazine of the International Guild of Knot Tyers Issue 92 - September 2006 www.igkt.net Except as otherwise indicated, copyright in Knotting Matters is reserved to the International Guild of Knot Tyers IGKT 2006. -

Federal Register/Vol. 82, No. 108/Wednesday, June 7, 2017

26340 Federal Register / Vol. 82, No. 108 / Wednesday, June 7, 2017 / Rules and Regulations Administrative Procedure Act (APA) certain archaeological and ethnological the imposition of these restrictions, and because this action is administrative in materials from Peru. The restrictions, included a list designating the types of nature. This action postpones the which were originally imposed by archaeological and ethnological effectiveness of the discharge Treasury Decision (T.D.) 97–50 and last materials covered by the restrictions. requirements in the regulations for extended by CBP Dec. 12–11, are due to These restrictions continued the CBNMS and GFNMS in the areas added expire on June 9, 2017, unless extended. protection of archaeological materials to the sanctuaries’ boundaries in 2015 The Acting Assistant Secretary for from the Sipa´n Archaeological Region (subject to notice and comment review) Educational and Cultural Affairs, United forming part of the remains of the with regard to USCG activities for six States Department of State, has Moche culture that were first subject to months to provide adequate time for determined that conditions continue to emergency import restriction on May 7, public scoping, completion of an warrant the imposition of import 1990 (T.D. 90–37). environmental assessment, and restrictions. The Designated List of Import restrictions listed in 19 CFR subsequent rulemaking, as appropriate. archaeological and ethnological 12.104g(a) are ‘‘effective for no more Should NOAA decide to amend the materials described in T.D. 97–50 is than five years beginning on the date on regulations governing discharges in revised in this document to reflect the which the agreement enters into force CBNMS and GFNMS, it would publish addition of Colonial period documents with respect to the United States. -

99272 Celtic Art : Book 1 1980 B/W Line Drawings Bain, George

Ref No Author Title Date Content ISBN 99193 - Postcards (Set of 8) Various knots I G K T 99492 Ashley, Clifford W The Book of Knots 1944 First Edition "SIGNED" (Estimated value £300) 99144 Admiralty Manual of Seamanship Vol 1, 2 & 3 (1981 & 1983) 1979 99143 Admiralty Manual of Seamanship Vol I 1937 99144 Admiralty Manual of Seamanship Vol I 1979 99144 Admiralty Manual of Seamanship Vol I 1979 99143 Admiralty Manual of Seamanship Vol II 1932 99144 Admiralty Manual of Seamanship Vol II 1981 99451 Admiralty, The Manual of Seamanship Vol 1 (1951) 1951 99121 Admiralty, The Seaman's Pocket Book 1943 B/W line drawings 99176 Aldridge, George Making Solid Sennets B/W line drawings 99155 Asher, Harry New System of Knotting Vol 1 1986 B/W line drawings I G K T 99155 Asher, Harry New System of Knotting Vol 2 1986 B/W line drawings I G K T 99150 Ashley, Clifford W Ashley Book of Knots 1946 THE basic knotting reference book 99488 Ashley, Clifford W. The Sailor and his Knots 2012 Original published in "Sea Stories Magazine" 1925 - This copy 1 of 100 0 9515506 9 1 99363 Ashley, Clifford W. Yankee Whaler, The 1991 Reprint of Ashleys book on whaling 0 486 26854 3 99399 Avery, Derek E. The New Encylopedia of Knots 1998 Text and drawings - package c/w cord 0-86019-000-5 99272 Bain, George Celtic Art : Book 1 1980 B/W line drawings 99273 Bain, George Celtic Art : Book 2, 3, 4 & 6 1980 B/W line drawings 99374 Bakker Azn, A. -

An Historical and Analytical Study of the Tally, The

Copyright by JttUa Slisabobh Adkina 1956 AN HISTORICAL AND ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE TALLY, THE KNOTTED CORD, THE FINGERS, AND THE ABACUS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U n iv e rsity Sy JULIA ELIZABETH ADKINS, A. B ., M. A. The Ohio State University 1936 Approved by: A dviser Department of Educati ACiCNOWLEDGMENT The author is deeply indebted to Professor Nathan lasar for his inspiration, guidance, and patience during the writing of this dissertation. IX lâBIfi OF CONTENTS GHAFTSl Fàm 1. INTRWCTION................................................................................... 1 Pl^iflËÜaaxy Statcum t ......................................................... 1 âtatamant of the Problem ............ 2 Sqportanee of the Problem ............................................. 3 Scope and Idmitationa of the S tu d y ............................................. 5 The Method o f the S tu d y ..................................................................... 5 BerLeir o f th e L i t e r a t u r e ............................................................ 6 Outline of the Remainder of the Study. ....................... 11 II. THE TâLLI .............................................. .................................................. 14 Definition and Etymology of "Tally? *. ...... .... 14 Types of T a llies .................................................................................. 16 The Notch T a lly ............................... -

![San Diego Public Library New Additions May 2009 [April 1, 2009 – May 14, 2009]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2271/san-diego-public-library-new-additions-may-2009-april-1-2009-may-14-2009-2382271.webp)

San Diego Public Library New Additions May 2009 [April 1, 2009 – May 14, 2009]

San Diego Public Library New Additions May 2009 [April 1, 2009 – May 14, 2009] Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks, eBooks & eVideos 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes Newspaper Room Audiovisual Materials Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/AALBORG Aalborg, Gordon. The horse tamer's challenge : a romance of the old west FIC/ADAMS Adams, Will, 1963- The Alexander cipher FIC/ADDIEGO Addiego, John. The islands of divine music FIC/ADLER Adler, H. G. The journey : a novel FIC/AGEE Agee, James, 1909-1955. A death in the family FIC/AIDAN Aidan, Pamela. Duty and desire : a novel of Fitzwilliam Darcy, gentleman FIC/AIDAN Aidan, Pamela. These three remain : a novel of Fitzwilliam Darcy, gentleman FIC/AKPAN Akpan, Uwem. Say you're one of them [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. The tale of Briar Bank : the cottage tales of Beatrix Potter [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. Wormwood FIC/ALBOM Albom, Mitch, 1958- The five people you meet in heaven FIC/ALLEN Allen, Jeffery Renard, 1962- Holding pattern : stories [SCI-FI] FIC/ALLSTON Allston, Aaron. Star wars : legacy of the force : betrayal FIC/AMBLER Ambler, Eric, 1909-1998. A coffin for Dimitrios FIC/AMIS Amis, Kingsley. Lucky Jim FIC/ANAYA Anaya, Rudolfo A. Bless me, Ultima FIC/ANAYA Anaya, Rudolfo A. The man who could fly and other stories [SCI-FI] FIC/ANDERSON Anderson, Kevin J., 1962- The ashes of worlds FIC/ANDERSON Anderson, Sherwood, 1876-1941. -

The Developments of Macramé As a Viable Economic Venture in Ghana

European Journal of Research and Reflection in Arts and Humanities Vol. 3 No. 4, 2015 ISSN 2056-5887 THE DEVELOPMENTS OF MACRAMÉ AS A VIABLE ECONOMIC VENTURE IN GHANA ABRAHAM EKOW ASMAH1, MILLICENT MATEKO MATE2. SAMUEL TEYE DAITEY3 1, 2, 3 Department of Integrated Rural Art and Industry, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, GHANA ABSTRACT The study of the developments of macramé as a viable economic venture in Ghana, attempts to examine the progressive development of macramé as an art and the available resource material for macramé production. It likewise attempts to expose an inclusive dint macramé have created in Ghana’s fashion, at the same time describing meticulously selected fashion accessories that have been made in macramé. The authors expounded that macramé has grown to be accepted as a potential, versatile, fashionable craft capable of complementing other fashionable accessory products for the adoption process in product development, which has a socioeconomic benefits as well as a sustaining culture. Some of the conclusions made are that macramé craft has become an entire facet of our traditional crafts, especially among the youth, and still undergoing progressively notable transformation. Keywords: Macramé, fashionable craft, developments, viable economic venture. INTRODUCTION Macramé as an element of decorative knots permeates virtually in every culture, but may manifest in different directions within these cultures (Jim Gentry, 2002). In Ghana, the meticulously braided cords became the element for forming fish nets, with the aid of a needle-like tool. The practice of knot making is predominantly practiced among youth scouts and cadets, especially in our second cycle institutions as part of their grooming sessions. -

Knotchartsweb.Pdf

International Guild of Knot Tyers Knot Charts Table of Contents Back Mooring Hitch ............................................................................. 3 Back Splice - 3 Strand Rope ................................................................. 4 Basic Picture Frames ............................................................................ 5 Bead Puzzle .......................................................................................... 6 Bottle (or Jar) Sling .............................................................................. 7 Bowlines - Multiple .............................................................................. 8 Carrick Bend & Mat Variations ........................................................... 9 Celtic Knot Design ............................................................................. 10 Chain Splice ........................................................................................ 11 Chinese Lanyard Knot ........................................................................ 12 Circular Mat ........................................................................................ 13 Clove Hitch Variations ....................................................................... 14 Coach Whipping ................................................................................. 15 Common Whipping Variations ........................................................... 16 Connecting Knots ............................................................................... 17 Constrictor