Arxiv:2108.04414V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 10 Aug 2021 Key Words: Galaxies: Evolution– Galaxies: Fundamental Parameters– Galaxies: ISM– Galaxies: Kinematics and Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps

W here Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps Abo ut the Activity Whe re are the distant worlds in the night sky? Use a star map to find constellations and to identify stars with extrasolar planets. (Northern Hemisphere only, naked eye) Topics Covered • How to find Constellations • Where we have found planets around other stars Participants Adults, teens, families with children 8 years and up If a school/youth group, 10 years and older 1 to 4 participants per map Materials Needed Location and Timing • Current month's Star Map for the Use this activity at a star party on a public (included) dark, clear night. Timing depends only • At least one set Planetary on how long you want to observe. Postcards with Key (included) • A small (red) flashlight • (Optional) Print list of Visible Stars with Planets (included) Included in This Packet Page Detailed Activity Description 2 Helpful Hints 4 Background Information 5 Planetary Postcards 7 Key Planetary Postcards 9 Star Maps 20 Visible Stars With Planets 33 © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Detailed Activity Description Leader’s Role Participants’ Roles (Anticipated) Introduction: To Ask: Who has heard that scientists have found planets around stars other than our own Sun? How many of these stars might you think have been found? Anyone ever see a star that has planets around it? (our own Sun, some may know of other stars) We can’t see the planets around other stars, but we can see the star. -

THE 1000 BRIGHTEST HIPASS GALAXIES: H I PROPERTIES B

The Astronomical Journal, 128:16–46, 2004 July A # 2004. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. THE 1000 BRIGHTEST HIPASS GALAXIES: H i PROPERTIES B. S. Koribalski,1 L. Staveley-Smith,1 V. A. Kilborn,1, 2 S. D. Ryder,3 R. C. Kraan-Korteweg,4 E. V. Ryan-Weber,1, 5 R. D. Ekers,1 H. Jerjen,6 P. A. Henning,7 M. E. Putman,8 M. A. Zwaan,5, 9 W. J. G. de Blok,1,10 M. R. Calabretta,1 M. J. Disney,10 R. F. Minchin,10 R. Bhathal,11 P. J. Boyce,10 M. J. Drinkwater,12 K. C. Freeman,6 B. K. Gibson,2 A. J. Green,13 R. F. Haynes,1 S. Juraszek,13 M. J. Kesteven,1 P. M. Knezek,14 S. Mader,1 M. Marquarding,1 M. Meyer,5 J. R. Mould,15 T. Oosterloo,16 J. O’Brien,1,6 R. M. Price,7 E. M. Sadler,13 A. Schro¨der,17 I. M. Stewart,17 F. Stootman,11 M. Waugh,1, 5 B. E. Warren,1, 6 R. L. Webster,5 and A. E. Wright1 Received 2002 October 30; accepted 2004 April 7 ABSTRACT We present the HIPASS Bright Galaxy Catalog (BGC), which contains the 1000 H i brightest galaxies in the southern sky as obtained from the H i Parkes All-Sky Survey (HIPASS). The selection of the brightest sources is basedontheirHi peak flux density (Speak k116 mJy) as measured from the spatially integrated HIPASS spectrum. 7 ; 10 The derived H i masses range from 10 to 4 10 M . -

H I Deficiency in Groups : What Can We Learn from Eridanus ?

Bull. Astr. Soc. India (2004) 32, 239{245 H i de¯ciency in groups : what can we learn from Eridanus ? A. Omar¤y Raman Research Institute, Sadashivanagar, Bangalore 560 080, India Received 14 July 2004; accepted 24 August 2004 Abstract. The H i content of the Eridanus group of galaxies is studied using the GMRT observations and the HIPASS data. A signi¯cant H i de¯ciency up to a factor of 2 ¡ 3 is observed in galaxies in the Eridanus group. The de¯ciency is found to be directly correlated with the projected galaxy density and inversely correlated with the line-of-sight radial velocity. It is suggested that the H i de¯ciency is due to tidal interactions. An important implication is that signi¯cant evolution of galaxies can take place in a group environment. Keywords : galaxies: ISM { galaxies: interactions { galaxies: kinematics and dynamics { galaxies: evolution { galaxies: clusters: individual: Eridanus group { radio lines: galaxies 1. Introduction Spiral galaxies in the cores of clusters are known to be H i de¯cient compared to their ¯eld counterparts (Davies and Lewis 1973, Giovanelli and Haynes 1985, Cayatte et al. 1990, Bravo-Alfaro et al. 2000). Several gas-removal mechanisms have been proposed to explain the H i de¯ciency in cluster galaxies. There are convincing results from both the simulations and the observations that ram-pressure stripping can be active in galaxies which have crossed the high ICM (Intra Cluster Medium) density region in the cores of clusters (Vollmer et al. 2001, van Gorkom 2003). However, it is not clear that all H i de¯cient galaxies have crossed the core. -

The Night Sky December

The Night Sky December Equipment you will need Because of the darkness of our forest locations, you can see many wonders of the night skies with your naked eye, although your eyes will Boötes need a good 20 minutes to adjust to the darkness. Any bright lights, such as that from your torch, will set them back again. You can reduce this effect by putting a red filter on your torch. Equipment worth investing in includes: Lynx • Binoculars – cheaper and easier to carry than a telescope. Look for ones with glass lenses. • Camera – to capture that fantastic star scene forever • Tripod – essential for use with your camera • Telescope – worth investing in for the really committed stargazer • Google Skymaps – a superb free app, available for Android and Delphinius iPhone. You point your phone towards the sky and it shows you the constellations and identifies the stars using inbuilt GPS Lepus Getting started – your first 5 constellations to spot • Ursa Major (the Big Dipper) has been used by sailors since ancient times to locate the fixed-point Pole Star and navigate home • Leo (the lion) is it a lion, as the Greeks decided? Or is it K9 from Doctor Who? • Cassiopeia (the queen of Aethiopia) is one of the easiest constellations to locate and looks like a huge W, almost directly overhead • Cepheus (the king of Aethiopia) is one of 48 constellations Eridanus identified by 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy. Imagine a child’s drawing of a house, complete with roof • Orion (the hunter), with belt and sword, is perhaps the most famous constellation – and one of the few that actually bears some slight resemblance to its namesake Stargazing facts for kids • You can see the International Space Station without using binoculars, and you can track it moving across the sky • The sun is 300,000 times bigger than earth and 93 million miles Boötes Lynx Delphinus Lepus Eridanus away. -

LIST of PUBLICATIONS Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences ARIES (An Autonomous Scientific Research Institute

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences ARIES (An Autonomous Scientific Research Institute of Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India) Manora Peak, Naini Tal - 263 129, India (1955−2020) ABBREVIATIONS AA: Astronomy and Astrophysics AASS: Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series ACTA: Acta Astronomica AJ: Astronomical Journal ANG: Annals de Geophysique Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal ASP: Astronomical Society of Pacific ASR: Advances in Space Research ASS: Astrophysics and Space Science AE: Atmospheric Environment ASL: Atmospheric Science Letters BA: Baltic Astronomy BAC: Bulletin Astronomical Institute of Czechoslovakia BASI: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India BIVS: Bulletin of the Indian Vacuum Society BNIS: Bulletin of National Institute of Sciences CJAA: Chinese Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics CS: Current Science EPS: Earth Planets Space GRL : Geophysical Research Letters IAU: International Astronomical Union IBVS: Information Bulletin on Variable Stars IJHS: Indian Journal of History of Science IJPAP: Indian Journal of Pure and Applied Physics IJRSP: Indian Journal of Radio and Space Physics INSA: Indian National Science Academy JAA: Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy JAMC: Journal of Applied Meterology and Climatology JATP: Journal of Atmospheric and Terrestrial Physics JBAA: Journal of British Astronomical Association JCAP: Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics JESS : Jr. of Earth System Science JGR : Journal of Geophysical Research JIGR: Journal of Indian -

WALLABY Pre-Pilot Survey: Two Dark Clouds in the Vicinity of NGC 1395

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley ScholarWorks @ UTRGV Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications and Presentations College of Sciences 2021 WALLABY pre-pilot survey: Two dark clouds in the vicinity of NGC 1395 O. I. Wong University of Western Australia A. R. H. Stevens B. Q. For University of Western Australia Tobias Westmeier M. Dixon See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/pa_fac Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation O I Wong, A R H Stevens, B-Q For, T Westmeier, M Dixon, S-H Oh, G I G Józsa, T N Reynolds, K Lee-Waddell, J Román, L Verdes-Montenegro, H M Courtois, D Pomarède, C Murugeshan, M T Whiting, K Bekki, F Bigiel, A Bosma, B Catinella, H Dénes, A Elagali, B W Holwerda, P Kamphuis, V A Kilborn, D Kleiner, B S Koribalski, F Lelli, J P Madrid, K B W McQuinn, A Popping, J Rhee, S Roychowdhury, T C Scott, C Sengupta, K Spekkens, L Staveley-Smith, B P Wakker, WALLABY pre-pilot survey: Two dark clouds in the vicinity of NGC 1395, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 2021;, stab2262, https://doi.org/10.1093/ mnras/stab2262 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Sciences at ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. -

A Guide to Star Names, Pronunciations, and Related Constellations

Astronomy Club of Asheville 3 Feb. 2020 version Page 1 of 8 A Guide to Star Names, Pronunciations, and Related Constellations Proper Star Names: There are over 300 proper star names that are used and accepted worldwide today -- and approved by the International Astronomical Union. Most of them come from the ancient Arabic cultures, but there are many star names in common use from the Greek, the Roman, European, and other cultures as well. On the pages below you will find an alphabetical list of many, but not all, of the proper star names, their pronunciations, and related constellations. Find a list of star names by constellation at this web link. Find another list of common star names at this web link. Star Catalogs that are Currently Used by Astronomers 1. Bayer Catalog: This first widely recognized star catalog was published by German astronomer Johann Bayer in 1603. This list of naked-eye stars indexes the stars in each constellation, using the letters of the Greek alphabet, followed by the genitive form of its parent constellation's Latin name, e.g., alpha Orionis. Typically, the brightest star in each constellation received the first Greek letter (alpha), the second brightest star the second letter (beta), and on-and-on. But you will often notice that the Bayer sequencing of the bright stars in the constellations is not true to what we see and know today about their apparent brightness. Original errors in the brightness estimates, along with the brightness variability of the stars (like Betelgeuse in Orion), have caused the Bayer sequencing not to match the stellar brightness that we observe today. -

The I Band Tully-Fisher Relation for Cluster Galaxies: Data Presentation

Dartmouth College Dartmouth Digital Commons Open Dartmouth: Peer-reviewed articles by Dartmouth faculty Faculty Work 10-13-1997 The I Band Tully-Fisher Relation for Cluster Galaxies: Data Presentation. Riccardo Giovanelli Cornell University Martha P. Haynes Cornell University Terry Herter Cornell University Nicole P. Vogt Cornell University Gary Wegner Dartmouth College See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons Dartmouth Digital Commons Citation Giovanelli, Riccardo; Haynes, Martha P.; Herter, Terry; Vogt, Nicole P.; Wegner, Gary; Salzer, John J.; da Costa, Luiz N.; and Freudling, Wolfram, "The I Band Tully-Fisher Relation for Cluster Galaxies: Data Presentation." (1997). Open Dartmouth: Peer-reviewed articles by Dartmouth faculty. 3427. https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa/3427 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Work at Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Dartmouth: Peer-reviewed articles by Dartmouth faculty by an authorized administrator of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Riccardo Giovanelli, Martha P. Haynes, Terry Herter, Nicole P. Vogt, Gary Wegner, John J. Salzer, Luiz N. da Costa, and Wolfram Freudling This article is available at Dartmouth Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa/3427 Version 1.1 13 October 1996 To appear in Astronomical Journal The I–Band Tully–Fisher Relation for Cluster Galaxies: Data Presentation Riccardo Giovanelli, Martha P. Haynes, Terry Herter and Nicole P. Vogt Center for Radiophysics and Space Research and National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center1, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 Gary Wegner Dept. -

Supernova Star Maps

Supernova Star Maps Which Stars in the Night Sky Will Go Su pernova? About the Activity Allow visitors to experience finding stars in the night sky that will eventually go supernova. Topics Covered Observation of stars that will one day go supernova Materials Needed • Copies of this month's Star Map for your visitors- print the Supernova Information Sheet on the back. • (Optional) Telescopes A S A Participants N t i d Activities are appropriate for families Cre with children over the age of 9, the general public, and school groups ages 9 and up. Any number of visitors may participate. Location and Timing This activity is perfect for a star party outdoors and can take a few minutes, up to 20 minutes, depending on the Included in This Packet Page length of the discussion about the Detailed Activity Description 2 questions on the Supernova Helpful Hints 5 Information Sheet. Discussion can start Supernova Information Sheet 6 while it is still light. Star Maps handouts 7 Background Information There is an Excel spreadsheet on the Supernova Star Maps Resource Page that lists all these stars with all their particulars. Search for Supernova Star Maps here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov/download-search.cfm © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Star Maps: Stars likely to go Supernova! Leader’s Role Participants’ Role (Anticipated) Materials: Star Map with Supernova Information sheet on back Objective: Allow visitors to experience finding stars in the night sky that will eventually go supernova. -

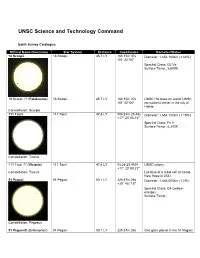

UNSC Science and Technology Command

UNSC Science and Technology Command Earth Survey Catalogue: Official Name/(Common) Star System Distance Coordinates Remarks/Status 18 Scorpii {TCP:p351} 18 Scorpii {Fact} 45.7 LY 16h 15m 37s Diameter: 1,654,100km (1.02R*) {Fact} -08° 22' 06" {Fact} Spectral Class: G2 Va {Fact} Surface Temp.: 5,800K {Fact} 18 Scorpii ?? (Falaknuma) 18 Scorpii {Fact} 45.7 LY 16h 15m 37s UNSC HQ base on world. UNSC {TCP:p351} {Fact} -08° 22' 06" recruitment center in the city of Halkia. {TCP:p355} Constellation: Scorpio 111 Tauri 111 Tauri {Fact} 47.8 LY 05h:24m:25.46s Diameter: 1,654,100km (1.19R*) {Fact} +17° 23' 00.72" {Fact} Spectral Class: F8 V {Fact} Surface Temp.: 6,200K {Fact} Constellation: Taurus 111 Tauri ?? (Victoria) 111 Tauri {Fact} 47.8 LY 05:24:25.4634 UNSC colony. {GoO:p31} {Fact} +17° 23' 00.72" Constellation: Taurus Location of a rebel cell at Camp New Hope in 2531. {GoO:p31} 51 Pegasi {Fact} 51 Pegasi {Fact} 50.1 LY 22h:57m:28s Diameter: 1,668,000km (1.2R*) {Fact} +20° 46' 7.8" {Fact} Spectral Class: G4 (yellow- orange) {Fact} Surface Temp.: Constellation: Pegasus 51 Pegasi-B (Bellerophon) 51 Pegasi 50.1 LY 22h:57m:28s Gas giant planet in the 51 Pegasi {Fact} +20° 46' 7.8" system informally named Bellerophon. Diameter: 196,000km. {Fact} Located on the edge of UNSC territory. {GoO:p15} Its moon, Pegasi Delta, contained a Covenant deuterium/tritium refinery destroyed by covert UNSC forces in 2545. {GoO:p13} Constellation: Pegasus 51 Pegasi-B-1 (Pegasi 51 Pegasi 50.1 LY 22h:57m:28s Moon of the gas giant planet 51 Delta) {GoO:p13} +20° 46' 7.8" Pegasi-B in the 51 Pegasi star Constellation: Pegasus system; a Covenant stronghold on the edge of UNSC territory. -

The Fundamentals of Stargazing Sky Tours South

The Fundamentals of Stargazing Sky Tours South 01 – The March Sky Copyright © 2014-2016 Mintaka Publishing Inc. www.CosmicPursuits.com -2- The Constellation Orion Let’s begin the tours of the deep-southern sky with the most famous and unmistakable constellation in the heavens, Orion, which will serve as a guide for other bright constellations in the southern late-summer sky. Head outdoors around 8 or 9 p.m. on an evening in early March, and turn towards the north. If you can’t find north, you can ask someone else, or get a small inexpensive compass, or use the GPS in your smartphone or tablet. But you need to face at least generally northward before you can proceed. You will also need a good unobstructed view of the sky in the north, so you may need to get away from structures and trees and so on. The bright stars of the constellation Orion (in this map, south is up and east is to the right) And bring a pair of binoculars if you have them, though they are not necessary for this tour. Fundamentals of Stargazing -3- Now that you’re facing north with a good view of a clear sky, make a 1/8th of a turn to your left. Now you are facing northwest, more or less. Turn your gaze upward about halfway to the point directly overhead. Look for three bright stars in a tidy line. They span a patch of sky about as wide as your three middle fingers held at arm’s length. This is the “belt” of the constellation Orion. -

CCD Double Star Measurements - Personal Observations: #Report 1

Vol. 8 No. 3 July 1, 2012 Journal of Double Star Observations Page 193 CCD Double Star Measurements - Personal Observations: #Report 1 Giuseppe Micello Bologna Emilia Romagna - Italy EMAIL: [email protected] Abstract: This report submits CCD measurements of 49 pairs, observed in the period No- vember 2011 – January 2012. Possible new pairs, not cataloged in the Washington Double Star Catalog, are suggested. Orionis (precise coordinate from the Aladin Sky At- Introduction las: 05:19:06.14 +02:34:27.0, Figure 3) and new pair Between November 2011 and January 2012, I in system STF 721/GUI 7/BU 557 (precise coordinate made measurements of 49 double and multiple stars. from the Aladin Sky Atlas: 05:29:39.01 +03:06:47.5, For these measurements, I used a Schmidt- Figure 4). Cassegrain 235/2350 and a Maksutov-Cassegrain In this system, GUI 7AD is a neglected double 150/1800 on equatorial mount and the optical train star and we have only one measurement, dating back composed of a CCD camera, Imaging Source to 1904. DMK21AU, and an IR Cut Filter on Flip Mirror. The method is the same that I reported in a pre- Acknowledgements vious papers [1, 2] where I used Reduc by Florent This research has made use of the catalogs pre- Losse for data reduction,. sent in The Aladin Sky Atlas. Astrometric measurements and references to im- I thank Florent Losse for excellent software Re- ages and notes, are included in Table 1. duc. This paper also includes new possible pairs not I thank the Washington Double Star Catalog and cataloged in the Washington Double Star Catalog [3].