Sidgwick and Eyring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George De Hevesy in America

Journal of Nuclear Medicine, published on July 13, 2019 as doi:10.2967/jnumed.119.233254 George de Hevesy in America George de Hevesy was a Hungarian radiochemist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1943 for the discovery of the radiotracer principle (1). As the radiotracer principle is the foundation of all diagnostic and therapeutic nuclear medicine procedures, Hevesy is widely considered the father of nuclear medicine (1). Although it is well-known that he spent time at a number of European institutions, it is not widely known that he also spent six weeks at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, in the fall of 1930 as that year’s Baker Lecturer in the Department of Chemistry (2-6). “[T]he Baker Lecturer gave two formal presentations per week, to a large and diverse audience and provided an informal seminar weekly for students and faculty members interested in the subject. The lecturer had an office in Baker Laboratory and was available to faculty and students for further discussion.” (7) There is also evidence that, “…Hevesy visited Harvard [University, Cambridge, MA] as a Baker Lecturer at Cornell in 1930…” (8). Neither of the authors of this Note/Letter was aware of Hevesy’s association with Cornell University despite our longstanding ties to Cornell until one of us (WCK) noticed the association in Hevesy’s biographical page on the official Nobel website (6). WCK obtained both his undergraduate degree and medical degree from Cornell in Ithaca and New York City, respectively, and spent his career in nuclear medicine. JRO did his nuclear medicine training at Columbia University and has subsequently been a faculty member of Weill Cornell Medical College for the last eleven years (with a brief tenure at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (affiliated with Cornell)), and is now the program director of the Nuclear Medicine residency and Chief of the Molecular Imaging and Therapeutics Section. -

A Brief History of Nuclear Astrophysics

A BRIEF HISTORY OF NUCLEAR ASTROPHYSICS PART I THE ENERGY OF THE SUN AND STARS Nikos Prantzos Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris Stellar Origin of Energy the Elements Nuclear Astrophysics Astronomy Nuclear Physics Thermodynamics: the energy of the Sun and the age of the Earth 1847 : Robert Julius von Mayer Sun heated by fall of meteors 1854 : Hermann von Helmholtz Gravitational energy of Kant’s contracting protosolar nebula of gas and dust turns into kinetic energy Timescale ~ EGrav/LSun ~ 30 My 1850s : William Thompson (Lord Kelvin) Sun heated at formation from meteorite fall, now « an incadescent liquid mass » cooling Age 10 – 100 My 1859: Charles Darwin Origin of species : Rate of erosion of the Weald valley is 1 inch/century or 22 miles wild (X 1100 feet high) in 300 My Such large Earth ages also required by geologists, like Charles Lyell A gaseous, contracting and heating Sun 푀⊙ Mean solar density : ~1.35 g/cc Sun liquid Incompressible = 4 3 푅 3 ⊙ 1870s: J. Homer Lane ; 1880s :August Ritter : Sun gaseous Compressible As it shrinks, it releases gravitational energy AND it gets hotter Earth Mayer – Kelvin - Helmholtz Helmholtz - Ritter A gaseous, contracting and heating Sun 푀⊙ Mean solar density : ~1.35 g/cc Sun liquid Incompressible = 4 3 푅 3 ⊙ 1870s: J. Homer Lane ; 1880s :August Ritter : Sun gaseous Compressible As it shrinks, it releases gravitational energy AND it gets hotter Earth Mayer – Kelvin - Helmholtz Helmholtz - Ritter A gaseous, contracting and heating Sun 푀⊙ Mean solar density : ~1.35 g/cc Sun liquid Incompressible = 4 3 푅 3 ⊙ 1870s: J. -

Europe's Biggest General Science Conference Concludes Successfully

SCIENCEScience PagesPAGES Special Report - ESOF 2016 Europe’s biggest generalSpecial Report science conference concludes successfully ESOF 2016, Europe's biggest general science conference concludes successfully in Manchester,in Manchester,UK UK Theme: Science as Revolution Theme: Science as Revolution - Veena Patwardhan rom 23rd to 27th July, 2016, FManchester flaunted its City of Science status as the host city of the seventh edition of EuroScience Open Forum (ESOF 2016). A bi- ennial event held in a different European city every two years, this time it was Manchester's turn to host this globally reputed science conference. Around 4500 delegates – scien- tists, innovators, academics, young researchers, journalists, policy makers, industry representatives and others – converged on the world's first industrial city to dis- cover and have discussions about the latest advancements in scien- rd th Manchester Central, venue of ESOF 2016 tific and technological researchFrom 23 to 27 July, 2016, Manchester flaunted its City of Science status as the host city of the across Europe and beyond. The seventhmain theme edition this of EuroScienceyear Laureates Open Forumand distinguished (ESOF 2016). Ascientists biennial inevent the held packed in a different was 'Science as Revolution', indicatingEuropean that city the every focus two of years,Exchange this time Hall it wasof Manchester Manchester's Central, turn to hostthe venuethis globally of the reputed the conference would be on how sciencescience andconference. technology conference. could transform life on the planet, revolutionise econo- The proceedings began with a string quartet render- mies, and help in overcoming challenges faced by global ing a piece of specially composed music. -

The Nobel Laureate George De Hevesy (1885-1966) - Universal Genius and Father of Nuclear Medicine Niese S* Am Silberblick 9, 01723 Wilsdruff, Germany

Open Access SAJ Biotechnology LETTER ISSN: 2375-6713 The Nobel Laureate George de Hevesy (1885-1966) - Universal Genius and Father of Nuclear Medicine Niese S* Am Silberblick 9, 01723 Wilsdruff, Germany *Corresponding author: Niese S, Am Silberblick 9, 01723 Wilsdruff, Germany, Tel: +49 35209 22849, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Niese S, The Nobel Laureate George de Hevesy (1885-1966) - Universal Genius and Father of Nuclear Medicine. SAJ Biotechnol 5: 102 Article history: Received: 20 March 2018, Accepted: 29 March 2018, Published: 03 April 2018 Abstract The scientific work of the universal genius the Nobel Laureate George de Hevesy who has discovered and developed news in physics, chemistry, geology, biology and medicine is described. Special attention is given to his work in life science which he had done in the second half of his scientific career and was the base of the development of nuclear medicine. Keywords: George de Hevesy; Radionuclides; Nuclear Medicine Introduction George de Hevesy has founded Radioanalytical Chemistry and Nuclear Medicine, discovered the element hafnium and first separated stable isotopes. He was an inventor in many disciplines and his interest was not only focused on the development and refinement of methods, but also on the structure of matter and its changes: atoms, molecules, cells, organs, plants, animals, men and cosmic objects. He was working under complicated political situation in Europe in the 20th century. During his stay in Germany, Austria, Hungary, Switzerland, Denmark, and Sweden he wrote a lot papers in German. In 1962 he edited a large part of his articles in a collection where German papers are translated in English [1]. -

Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science

Nuclear Science—A Guide to the Nuclear Science Wall Chart ©2018 Contemporary Physics Education Project (CPEP) Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science Many Nobel Prizes have been awarded for nuclear research and instrumentation. The field has spun off: particle physics, nuclear astrophysics, nuclear power reactors, nuclear medicine, and nuclear weapons. Understanding how the nucleus works and applying that knowledge to technology has been one of the most significant accomplishments of twentieth century scientific research. Each prize was awarded for physics unless otherwise noted. Name(s) Discovery Year Henri Becquerel, Pierre Discovered spontaneous radioactivity 1903 Curie, and Marie Curie Ernest Rutherford Work on the disintegration of the elements and 1908 chemistry of radioactive elements (chem) Marie Curie Discovery of radium and polonium 1911 (chem) Frederick Soddy Work on chemistry of radioactive substances 1921 including the origin and nature of radioactive (chem) isotopes Francis Aston Discovery of isotopes in many non-radioactive 1922 elements, also enunciated the whole-number rule of (chem) atomic masses Charles Wilson Development of the cloud chamber for detecting 1927 charged particles Harold Urey Discovery of heavy hydrogen (deuterium) 1934 (chem) Frederic Joliot and Synthesis of several new radioactive elements 1935 Irene Joliot-Curie (chem) James Chadwick Discovery of the neutron 1935 Carl David Anderson Discovery of the positron 1936 Enrico Fermi New radioactive elements produced by neutron 1938 irradiation Ernest Lawrence -

ARIE SKLODOWSKA CURIE Opened up the Science of Radioactivity

ARIE SKLODOWSKA CURIE opened up the science of radioactivity. She is best known as the discoverer of the radioactive elements polonium and radium and as the first person to win two Nobel prizes. For scientists and the public, her radium was a key to a basic change in our understanding of matter and energy. Her work not only influenced the development of fundamental science but also ushered in a new era in medical research and treatment. This file contains most of the text of the Web exhibit “Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity” at http://www.aip.org/history/curie/contents.htm. You must visit the Web exhibit to explore hyperlinks within the exhibit and to other exhibits. Material in this document is copyright © American Institute of Physics and Naomi Pasachoff and is based on the book Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity by Naomi Pasachoff, Oxford University Press, copyright © 1996 by Naomi Pasachoff. Site created 2000, revised May 2005 http://www.aip.org/history/curie/contents.htm Page 1 of 79 Table of Contents Polish Girlhood (1867-1891) 3 Nation and Family 3 The Floating University 6 The Governess 6 The Periodic Table of Elements 10 Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834-1907) 10 Elements and Their Properties 10 Classifying the Elements 12 A Student in Paris (1891-1897) 13 Years of Study 13 Love and Marriage 15 Working Wife and Mother 18 Work and Family 20 Pierre Curie (1859-1906) 21 Radioactivity: The Unstable Nucleus and its Uses 23 Uses of Radioactivity 25 Radium and Radioactivity 26 On a New, Strongly Radio-active Substance -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 4 - 1996 to 2015: from Stem Cell Breakthrough to IVF

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 4 - 1996 to 2015: from stem cell breakthrough to IVF By Cambridge News | Posted: February 01, 2016 Some of Cambridge's most recent Nobel winners Over the last four weeks the News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, which this week comes right up to the present day. From the early giants of physics like JJ Thomson and Ernest Rutherford to the modern-day biochemists unlocking the secrets of our genome, we've covered the length and breadth of scientific discovery, as well as hugely influential figures in economics, literature and politics. What has stood out is the importance of collaboration; while outstanding individuals have always shone, Cambridge has consistently achieved where experts have come together to bounce their ideas off each other. Key figures like Max Perutz, Alan Hodgkin and Fred Sanger have not only won their own Nobels, but are regularly cited by future winners as their inspiration, as their students went on to push at the boundaries they established. In the final part of our feature we cover the last 20 years, when Cambridge has won an average of a Nobel Prize a year, and shows no sign of slowing down, with ground-breaking research still taking place in our midst today. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1.1996 James Mirrlees, Trinity College: Prize in Economics, for studying behaviour in the absence of complete information As a schoolboy in Galloway, Scotland, Mirrlees was in line for a Cambridge scholarship, but was forced to change his plans when on the weekend of his interview he was rushed to hospital with peritonitis. -

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY Theo James presenting a bouquet to HM The Queen on the occasion of her bicentenary visit, 7 December 1999. by Frank A.J.L. James The Director, Susan Greenfield, looks on Front page: Façade of the Royal Institution added in 1837. Watercolour by T.H. Shepherd or more than two hundred years the Royal Institution of Great The Royal Institution was founded at a meeting on 7 March 1799 at FBritain has been at the centre of scientific research and the the Soho Square house of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph popularisation of science in this country. Within its walls some of the Banks (1743-1820). A list of fifty-eight names was read of gentlemen major scientific discoveries of the last two centuries have been made. who had agreed to contribute fifty guineas each to be a Proprietor of Chemists and physicists - such as Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday, a new John Tyndall, James Dewar, Lord Rayleigh, William Henry Bragg, INSTITUTION FOR DIFFUSING THE KNOWLEDGE, AND FACILITATING Henry Dale, Eric Rideal, William Lawrence Bragg and George Porter THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION, OF USEFUL MECHANICAL - carried out much of their major research here. The technological INVENTIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS; AND FOR TEACHING, BY COURSES applications of some of this research has transformed the way we OF PHILOSOPHICAL LECTURES AND EXPERIMENTS, THE APPLICATION live. Furthermore, most of these scientists were first rate OF SCIENCE TO THE COMMON PURPOSES OF LIFE. communicators who were able to inspire their audiences with an appreciation of science. -

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Cyril Norman Hinshelwood

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Cyril Norman Hinshelwood Name: Cyril Norman Hinshelwood Lebensdaten: 19. Juni 1897 ‐ 9. Oktober 1967 Cyril Norman Hinshelwood war ein britischer Chemiker. Er untersuchte Aspekte der chemischen Reaktionskinetik. Nach ihm ist der Langmuir‐Hinshelwood‐Mechanismus benannt. Er beschreibt die Reaktion zweier Ausgangsstoffe an einer Katalysator‐Oberfläche. Für seine Forschungen über die Mechanismen chemischer Reaktion wurde Hinshelwood 1956 mit dem Nobelpreis für Chemie ausgezeichnet. Akademischer und beruflicher Werdegang Cyril Norman Hinshelwood war sehr begabt und bekam ein Stipendium für die University of Oxford zugesprochen. Wegen des Ersten Weltkriegs konnte er dies jedoch nicht in Anspruch nehmen. Stattdessen war er in dieser Zeit als Chemiker in einer Sprengstofffabrik in Queensferry, Schottland tätig. 1919 ging er ans Balliol College in Oxford, wo er einen durch die Nachkriegszeit verkürzten Kurs in Chemie besuchen durfte. Seine Auffassungsgabe der chemischen Prinzipien war so herausragend, dass er erneut für ein Stipendium vorgeschlagen wurde. In Oxford erlangte Hinshelwood den Bachelor‐ und Master‐Grad. Von 1921 bis 1937 arbeitete er am Trinity College in Oxford als Tutor. 1937 erhielt er eine Professur für Chemie an der Universität Oxford. Auch während des Zweiten Weltkriegs war er für die Kriegsproduktion tätig, so unter anderem bei der Herstellung von Gasmasken und Penicillin. Nobelpreis für Chemie 1956 Die chemische Kinetik, die Geschwindigkeit und Mechanismus einer chemischen Reaktion untersucht, war zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts noch wenig erforscht. Hinshelwood hatte großes Interesse an den Mechanismen derartiger chemischer Prozesse. Es wurde während des Ersten Weltkriegs noch verstärkt, als er in einer Munitionsfabrik beschäftigt war, wo er sich mit der Chemie von explosiven Stoffen beschäftigte. -

Back Matter (PDF)

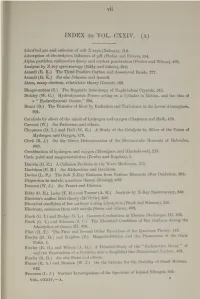

V ll INDEX to VOL. CXXIV. (A) Adsorbed gas and emission of soft X-rays (Nakaya), 61G. Adsorption of electrolytes, influence of (Phelps and Peters), 554. Alpha particles, radioactive decay and nuclear penetration (Fowler and Wilson), 493. Analysis by X-ray spectroscopy (Eddy and others), 249. Asundi (R. K.) The Third Positive Carbon and Associated Bands, 277. Asundi (R. K.) See also Johnson and Asundi. Atom, many-electron, relativistic theory (Gaunt), 163. Bhagavantam (S.) The Magnetic Anisotropy of Naphthalene Crystals, 545. Bickley (W. G.) Hydrodynamic Forces acting on a Cylinder in Motion, and the idea of a “ Hydrodynamic Centre,” 296. Brunt (D.) The Transfer of Heat by Radiation and Turbulence in the Lower Atmosphere, 201. Catalysis by silver of the union of hydrogen and oxygen (Chapman and Hall), 478. Cawood (W.) See Patterson and others. Chapman (D. L.) and Hall (W. K.) A Study of the Catalysis by Silver of the Union of Hydrogen and Oxygen, 478. Clark (R. J.) On the Direct Determination of the Electrostatic Moments of Molecules, 689. Combination of hydrogen and oxygen (Thompson and Hinshelwood), 219. Curie point and magnetostriction (Fowler and Kapitza), 1. Darwin (G. C.) A Collision Problem in the Wave Mechanics, 375. Davidson (P. M.) See Richardson and Davidson. Davies (L. P.) The Soft X-Ray Emission from Various Elements after Oxidation, 268. Dispersion in metals, quantum theory (Kronig), 409. Duncan (W. J.) See Frazer and Duncan. Eddy (C. E.), Laby (T. H.) and Turner (A. H.) Analysis by X-Ray Spectroscopy, 249. Einstein’s unified field theory (McVittie), 366. Electrical condition of hot surfaces during adsorption (Finch and Stimson), 356. -

Named Equations and Laws in Chemistry (H – K)

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Named-EQ(H-K).pdf 1 NAMED EQUATIONS AND LAWS IN CHEMISTRY (H – K) © Dr. John Andraos, 2000 - 2011 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ John Burdon Sanderson Haldane 5 November 1882 - 1 December 1964 British-Scottish, b. Oxford, England Haldane equation Haldane, J.B.S., Enzymes , Longmans, Green, & Co.: London, 1930 Briggs-Haldane solution see George Edward Briggs Biographical References: Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D ., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists , Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Millar, D.; Millar, I.; Millar, J.; Millar, M., Chambers Concise Dictionary of Scientists , W. & R. Chambers: Edinburgh, 1989 Pirie, N.W., Biog. Memoirs Fellows Roy. Soc., 1966 , 12 , 219 Louis Plack Hammett 7 April 1894 - 9 February 1987 American, b. Wilmington, Delaware, USA Hammett equation Hammett sigma constants Hammett, L.P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1937 , 59 , 96 Hammett, L.P., Chem. Rev. 1935 , 17 , 125 Hammett acidity function Hammett, L.P.; Deyrup, A.J., J. Am. Chem. Soc . 1932 , 54 , 2721 2 Biographical References: Westheimer, F.H., Biog. Memoirs Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997 , 72 , 137 Anon., Chem. Eng. News 1998 , 76 (2), 171 Charles Samuel Hanes 21 May 1903 - 6 July 1990 Canadian, b. Toronto, Ontario, Canada Hanes-Woolf plot Hanes, C.S., Biochem. J. 1932 , 26 , 1406 Woolf's contributions cited in Haldane, J.B.S.; Stern, K.G. Allgemeine Chemie der Enzyme , Steinkopff: Dresden, Leipzig, 1932 though Woolf did not publish his own papers. -

The World Around Is Physics

The world around is physics Life in science is hard What we see is engineering Chemistry is harder There is no money in chemistry Future is uncertain There is no need of chemistry Therefore, it is not my option I don’t have to learn chemistry Chemistry is life Chemistry is chemicals Chemistry is memorizing things Chemistry is smell Chemistry is this and that- not sure Chemistry is fumes Chemistry is boring Chemistry is pollution Chemistry does not excite Chemistry is poison Chemistry is a finished subject Chemistry is dirty Chemistry - stands on the legacy of giants Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794) Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867- 1934) John Dalton (1766- 1844) Sir Humphrey Davy (1778 – 1829) Michael Faraday (1791 – 1867) Chemistry – our legacy Mendeleev's Periodic Table Modern Periodic Table Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834-1907) Joseph John Thomson (1856 –1940) Great experimentalists Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858 –1937) Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (1888-1970) Chemistry and chemical bond Gilbert Newton Lewis (1875 –1946) Harold Clayton Urey (1893- 1981) Glenn Theodore Seaborg (1912- 1999) Linus Carl Pauling (1901– 1994) Master craftsmen Robert Burns Woodward (1917 – 1979) Chemistry and the world Fritz Haber (1868 – 1934) Machines in science R. E. Smalley Great teachers Graduate students : Other students : 1. Werner Heisenberg 1. Herbert Kroemer 2. Wolfgang Pauli 2. Linus Pauling 3. Peter Debye 3. Walter Heitler 4. Paul Sophus Epstein 4. Walter Romberg 5. Hans Bethe 6. Ernst Guillemin 7. Karl Bechert 8. Paul Peter Ewald 9. Herbert Fröhlich 10. Erwin Fues 11. Helmut Hönl 12. Ludwig Hopf 13. Walther Kossel 14.