Download This Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angola Preparedness for Resilient Recovery Project Final Report

FINAL PROJECT REPORT SEPTEMBER, 2017 United Nations Development Programme, Angola Project ID and Title: 00048055, Preparedness for Resilient Recovery Original Project Period: 9/2014 - 9/2016 Revised Project Period: 9/2014 - 9/2017 Reporting Period: 9/2014 - 9/2017 Total Project Budget for Angola: US$ 324,000 financed by the Japan-UNDP Partnership Fund National Priorities: - Contribute to sustainable development by ensuring the preservation of the environment and quality of life of citizens. - Promotion of growth and economic diversification, national enterprises, and employment (including the insertion of the youth in active life). UNPAF Outcome involving UNDP: 4. By 2019, the environmental sustainability is strengthened through the improvement of management of energy, natural resources, access to green technology, climate change strategies, conservation of biodiversity, and systems and plans to reduce disasters and risks. Expected Country Programme Output: 4.2 Preparedness systems in place to effectively address the consequences of and response to risks posed by natural and man-made disasters at all levels of government and community. Final Project Report - 1/37 Contents 1. EXEUCUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................. 3 2. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................. 4 3. IMPLEMENTATION RESULTS ........................................................................ 6 4. IMPLEMENTATION CHALLENGE ................................................................ -

Radon Concentration Potential in Bibala Municipality Water: Consequences for Public Consumption

Radon Concentration Potential in Bibala Municipality Water: Consequences for Public Consumption Joaquim Kessongoa,c, Yoenls Bahua,c, Margarida Inácioa,c, Pedro Almeidad,e, Luis Peraltac,e, Sandra Soaresa,b,c aDepartamento de Física, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal bCentro de Matemática e aplicações da Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal cLaboratório de instrumentação e Física Experimental de Partículas, Lisboa, Portugal dDepartamento de Engenharia Civil e Arquitetura, Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal eFaculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal Abstract The primary motivation for this work is the evaluation of the radon concentration in portable water for human consumption in Bibala, a municipality in Angola, where granitic rocks are common, and contain a high concentration of uranium that can be mobilized in underground water. Radon is the largest contributor of radioactive pollution in underground water. Its concentration in water, represents a public health risk due to the fact that the gas can easily escape into the air, adding to the total indoor concentration of radon. On the other hand, ingestion of water with a high radon concentration represents an additional risk to the stomach. Measurements of radon concentration, in Bibala municipality’s water, were performed on 16 samples obtained from wells of various depths and analyzed with DURRIDGEs’ RAD7 equipment. Measured concentrations are in the range from 39.5 to 202 Bq L−1, with 2 of the recovered samples presenting values over 100 Bq L−1. Keywords: Radon, Water, Dosimetry, Bibala 1. Introduction Since the beginning of the world human beings have been exposed to natural radiation deriving from the earth as well as from outside. -

Angola: Country Profile Report

ANGOLA: COUNTRY PROFILE REPORT 2020-21 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................. 5 LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................... 6 COUNTRY FACT SHEET ..................................................................................................... 7 LIST OF ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................... 8 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 10 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ...................................................................... 13 1.1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 13 1.2. Objectives of the Report........................................................................................ 13 1.3. Focus of the Report .............................................................................................. 14 1.4. Methodology ......................................................................................................... 14 1.5. Structure of the Report .......................................................................................... 14 2. OVERVIEW OF ANGOLA -

ANGOLA FOOD SECURITY UPDATE July 2003

ANGOLA FOOD SECURITY UPDATE July 2003 Highlights The food security situation continues to improve in parts of the country, with the overall number of people estimated to need food assistance reduced by four percent in July 2003 relieving pressure on the food aid pipeline. The price of the least-expensive food basket also continues to decline after the main harvest, reflecting an improvement in access to food. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the results of both the latest nutritional surveys as well as the trend analysis on admissions and readmissions to nutritional rehabilitation programs indicate a clear improvement in the nutritional situation of people in the provinces considered at risk (Benguela, Bie, Kuando Kubango). However, the situation in Huambo and Huila Provinces still warrants some concern. Household food stocks are beginning to run out just two months after the main harvest in the Planalto area, especially for the displaced and returnee populations. In response to the current food crisis, relief agencies in Angola have intensified their relief efforts in food insecure areas, particularly in the Planalto. More than 37,000 returnees have been registered for food assistance in Huambo, Benguela, Huila and Kuando Kubango. The current food aid pipeline looks good. Cereal availability has improved following recent donor contributions of maize. Cereal and pulse projections indicate that total requirements will be covered until the end of October 2003. Since the planned number of beneficiaries for June and July 2003 decreased by four percent, it is estimated that the overall availability of commodities will cover local food needs until end of November 2003. -

Concerned Governments Angola - Mainly Complaints by Angola Against South Africa's Military Attacks

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 113 Date 06/06/2006 Time 11:29:25 AM S-0902-0005-01-00001 Expanded Number S-0902-0005-01 -00001 Title items-in-Africa - Question of Namibia - concerned governments Angola - mainly complaints by Angola against South Africa's military attacks Date Created 26/02/1979 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0902-0005: Peacekeeping - Africa 1963-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit / , jl 1 V t L/ •iOV •• .; 138'i No. 134/1981 November 11, 1981 H.E. Dr. Kurt Waldheim Secretary General United Nations, New York Excellency, Attached please find a copy of my communication to the President of the Security Council, which has relevance not only to the sixth anniversary of the independence of the People's Republic of Angola, but also to the aggression Angola continues to face at the hands of the racist apartheid regime in South Africa. The situation poses as serious threat to the peace stability of southern Africa. Accept, Excellency, the assurances of my highest consideration. .Isio de Figueiredo 5SADOR PERMANEIS7T REPRESENTATIVE OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA TO THE UNITED NATIONS Permanent Mission of The People's Republic of Angola to the United Nations 747 Third Avenue (18th floor) New York, N.Y. 10017 (212)752-4612 No. 133/1981 November 11, 1981 H.E. Mr. Taieb Slim President of the Security Council United Nations New York Excellency, Today, 11 November 1981, the Government and people of the People's Republic of Angola, guided by the Central Commit- tee of the MPLA-Workers Party, are commemorating the sixth an- niversary of their declaration of independence and their free- dom from the oppression and exploitation of five hundred years of colonial domination. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A B ell & Howell Information Company 300 NorthZeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 LUSO-AFRJCAN REAL MARAVILLOSCP.-. A STUDY ON THE CONVERGENCE OF LATIN AMERICAN AND LUSO-AFRICAN LITERATURES DISSERTATION Presented in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Bv Hanna Betina Gotz The Ohio State University 1998 Dissertation committee: Approved by Dr. -

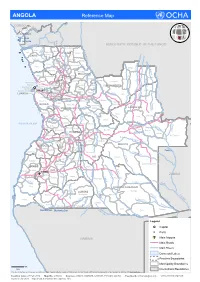

ANGOLA Reference Map

ANGOLA Reference Map CONGO L Belize ua ng Buco Zau o CABINDA Landana Lac Nieba u l Lac Vundu i Cabinda w Congo K DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO o z Maquela do Zombo o p Noqui e Kuimba C Soyo M Mbanza UÍGE Kimbele u -Kongo a n ZAIRE e Damba g g o id Tomboco br Buengas M Milunga I n Songo k a Bembe i C p Mucaba s Sanza Pombo a i a u L Nzeto c u a i L l Chitato b Uige Bungo e h o e d C m Ambuila g e Puri Massango b Negage o MALANGE L Ambriz Kangola o u Nambuangongo b a n Kambulo Kitexe C Ambaca m Marimba g a Kuilo Lukapa h u Kuango i Kalandula C Dande Bolongongo Kaungula e u Sambizanga Dembos Kiculungo Kunda- m Maianga Rangel b Cacuaco Bula-Atumba Banga Kahombo ia-Baze LUNDA NORTE e Kilamba Kiaxi o o Cazenga eng Samba d Ingombota B Ngonguembo Kiuaba n Pango- -Caju a Saurimo Barra Do Cuanza LuanCda u u Golungo-Alto -Nzoji Viana a Kela L Samba Aluquem Lukala Lul o LUANDA nz o Lubalo a Kazengo Kakuso m i Kambambe Malanje h Icolo e Bengo Mukari c a KWANZA-NORTE Xa-Muteba u Kissama Kangandala L Kapenda- L Libolo u BENGO Mussende Kamulemba e L m onga Kambundi- ando b KWANZA-SUL Lu Katembo LUNDA SUL e Kilenda Lukembo Porto Amboim C Kakolo u Amboim Kibala t Mukonda Cu a Dala Luau v t o o Ebo Kirima Konda Ca s Z ATLANTIC OCEAN Waco Kungo Andulo ai Nharea Kamanongue C a Seles hif m um b Sumbe Bailundo Mungo ag e Leua a z Kassongue Kuemba Kameia i C u HUAMBO Kunhinga Luena vo Luakano Lobito Bocoio Londuimbali Katabola Alto Zambeze Moxico Balombo Kachiungo Lun bela gue-B Catum Ekunha Chinguar Kuito Kamakupa ungo a Benguela Chinjenje z Huambo n MOXICO -

Puuns 1 9 8 7 0

5. A group of students from a Jewish religious school in oc- 5. A group of students from a Jewish religious school in occupied Arab Jerusalem took over nine rooms of an Arab house in the city on 23 August, claiming that the rooms had previously belonged to Jews. The operation took place with the full co- operation of the Israeli police, which did not intervene to restrain the attackers and provided them with the necessary protection. 6. On 30 August "unidentified persons" attacked Arab land planted with trees in the village of Sarrah (Nablus district) and set fire to the trees. This caused the destruction of hundreds ofdunums of land planted with fruit trees and olive trees. 7. On 2 September Israeli army bulldozers laid a new road linking the settlement of Alfe Menasheh with the main road from Qalqilya to Nablus. The road passes through land owned by Arab citizens. The Israeli bulldoter work caused dozens of fruit trees to be uprooted. 8. Israeli army forces attacked 200 dunums of Arab land in the Sheikh Sa'd area. east of the city of Bethlehem. on 21 September and tore up the boundary markers in preparation for its confiscation. 9. Settlers from the Ma'ale Amos settlement, east of Bethlehem. attacked an Arab citizen's land adjacent to their settlement in a region known as - Sahbah" on 22 September, uprooted some 200 cultivated olive trees and destroyed them. 10. "Unidentified persons" attacked the citrus nursery of an Arab citizen in Qalqilya on 22 September and destroyed 3,000 citrus trees in the nursery, using incendiary chemical substances. -

Angola Livelihood Zone Report

ANGOLA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions November 2013 ANGOLA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions November 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………................……….…........……...3 Acronyms and Abbreviations……….………………………………………………………………......…………………....4 Introduction………….…………………………………………………………………………………………......………..5 Livelihood Zoning and Description Methodology……..……………………....………………………......…….…………..5 Livelihoods in Rural Angola….………........………………………………………………………….......……....…………..7 Recent Events Affecting Food Security and Livelihoods………………………...………………………..…….....………..9 Coastal Fishing Horticulture and Non-Farm Income Zone (Livelihood Zone 01)…………….………..…....…………...10 Transitional Banana and Pineapple Farming Zone (Livelihood Zone 02)……….……………………….….....…………..14 Southern Livestock Millet and Sorghum Zone (Livelihood Zone 03)………….………………………….....……..……..17 Sub Humid Livestock and Maize (Livelihood Zone 04)…………………………………...………………………..……..20 Mid-Eastern Cassava and Forest (Livelihood Zone 05)………………..……………………………………….……..…..23 Central Highlands Potato and Vegetable (Livelihood Zone 06)..……………………………………………….………..26 Central Hihghlands Maize and Beans (Livelihood Zone 07)..………..…………………………………………….……..29 Transitional Lowland Maize Cassava and Beans (Livelihood Zone 08)......……………………...………………………..32 Tropical Forest Cassava Banana and Coffee (Livelihood Zone 09)……......……………………………………………..35 Savannah Forest and Market Orientated Cassava (Livelihood Zone 10)…….....………………………………………..38 Savannah Forest and Subsistence Cassava -

Economy of Angola

ix Acknowledgements Many persons have contributed to this book through discussions, debate and insight. We would particularly like to express our sincere thanks and appreciation to the members of the Institute for Security Studies who continue to provide inci- sive analysis of the conflicts ravaging the African continent. Our appreciation to the Government of Finland through whose generous funding this publication has been made possible and specifically to Pekka Orpana. We would also like to acknowledge the excellence, professionalism and enthu- siasm of our authors. Christian Dietrich would like to record a word of thanks to Virginia Gamba and Jakkie Potgieter for their kindness following his accident and Jakkie Cilliers would like to express his appreciation for the support and patience of Ulrika Soneson. Finally, we would like to thank Alice Coetzee for her superb editorial assistance. Jakkie Cilliers and Christian Dietrich Pretoria September 2000 x K 14° Brazzaville 18° as 22° 4° CONGO ai 4° Kinshasa ANGOLA DA IN e B ir Kikwit A a DEMOCRATIC C Z K K w REPUBLIC w Cabinda i a l OF THE u n g e o g Nóqui CONGO an Lo Soyo M'banza Congo K w ANGOLA e ZAIRE e Quimbele n g C W id Damba g K br u e a M a s a m a Bembe UÍGE n L i g b u o a N'zeto Bungo a n Dundo e g og Uíge u L e a Ambriz Negage p a U Andrada 8° Cuilo c 8° i a Marimba h de m Lucapa Caxito Dan Camabatela b C L a LUNDA i u o CUANZA Luremo a c b s Luanda O a s m NORTE l NORTE a a Cuango a L G C N'dalatando Quela C u l LUANDA Malanje Lubalo u N o a Lucala l E Dondo i Saurimo Cabo -

Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties Under Article 40 of the Covenant

United Nations CCPR /C/AGO/1 International Covenant on Distr.: General Civil and Political Rights 3 March 2011 Original: English Human Rights Committee Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 40 of the Covenant First periodic report Angola * [17 February 2011] * * In accordance with the information transmitted to States parties regarding the processing of their reports, the present document was not formally edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. GE.11-41591 (E) 280311 CCPR/C/AGO/1 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction.............................................................................................................. 1–7 3 II. Legal and constitutional framework......................................................................... 8–14 4 III. Realization of civil and political rights.................................................................... 15–111 5 A. Self–determination and independence (art. 1)................................................. 16–20 6 B. Non–discrimination (arts. 2, 14 and 27).......................................................... 21–22 6 C. Equality of men and women (art. 3)................................................................ 23–25 7 D. Emergency situations, disasters and risks (art. 4)............................................ 26–30 7 E. Right to life (art. 6).......................................................................................... 31–35 8 F. Persons deprived of liberty (arts. 7 and 10).................................................... -

ANGOLA “THEY WANT to KEEP US VULNERABLE” HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS UNDER PRESSURE Fact-Finding Mission Report

a joint programme ANGOLA “THEY WANT TO KEEP US VULNERABLE” HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS UNDER PRESSURE Fact-Finding Mission Report March 2015 Cover photo: A group of young Angolans demonstrate at the place of Independence in the centre of Luanda on May 27, 2013 to protest against the enforced disappearance of two of their colleagues in 2012. The demonstration was violently dispersed by the police. Photograph by Estelle Maussion / AFP PHOTO Directors of publication: Karim Lahidji, Gerald Staberock Authors of the report: Thomas Masuku, Alexandra Montgomery, Tchérina Jerolon, Maria Lúcia da Silveira Edition and coordination: Tchérina Jerolon Design: CBT / Lay out: Stéphanie Geel Imprimerie de la FIDH Dépôt légal mars 2015 FIDH (English ed.) ISSN 2225-1804 – Fichier informatique conforme à la loi du 6 janvier 1978 (Déclaration N° 330 675) 2 The Observatory / AJPD ANGOLA: “THEY WANT TO KEEP US VULNERABLE” – HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS UNDER PRESSURE TABLE OF CONTENTS • Map of Angola. 4 • List of Acronyms. 5 INTRODUCTION – PURPOSES OF THE MISSION ......................................... 6 I. HISTORICAL, POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND HUMAN RIGHTS CONTEXT . 7 • From war to economic performances and political influence ........................7 • Supremacy of the MPLA and its Executive. 8 • Widespread poverty, huge disparities and endemic corruption ......................8 • Police brutality and impunity ....................................................9 • The situation in the Cabinda province ...........................................10 II. THE HUMAN RIGHTS LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK . 11 A. The national human rights legal framework ......................................11 B. The deficiencies of the Angolan judiciary . 12 C. The national institutions mandated to promote and protect human rights. 13 III. PATTERNS OF VIOLATIONS OF THE RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS . .15 A.