Danish Football at the Crossroads - an Analysis on Options for a Future League Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Europe Antepost Coupon 2019/20 08/10/2019 10:36 1 / 7

Issued Date Page EUROPE ANTEPOST COUPON 2019/20 08/10/2019 10:36 1 / 7 Spain Primera Division 2019/20 France Ligue 1 2019/20 Belgium First Division A 2019/20 Italy Serie A 2019/20 Runners Winner Runners Winner Runners Winner Runners Winner FC Barcelona 1.65 Paris Saint-Germain 1.02 Club Brugge 1.50 Juventus Turin 1.40 Real Madrid 2.55 Olympique Lyonnais 22.0 Standard Liege 5.50 Inter Milano 4.50 Atletico Madrid 13.3 Lille Losc 45.0 KAA Gent 9.00 SSC Napoli 7.50 FC Sevilla 52.0 Olympique Marseille 66.0 KRC Genk 9.00 Atalanta Bergamasca Calcio 28.0 CF Valencia 130 FC Nantes 72.0 Royal Antwerp FC 9.00 AS Roma 64.0 Real Sociedad 150 AS Monaco 76.0 RSC Anderlecht 29.0 SS Lazio Roma 145 Portugal Primera Liga 2019/20 Turkey Super Lig 2019/20 Greece Super League 2019/20 Cyprus 1st Division 2019/20 Runners Winner Runners Winner Runners Winner Runners Winner Benfica Lisbon 1.85 Galatasaray 2.40 Olympiacos FC 1.50 Apoel Nicosia FC 1.65 FC Porto 2.05 Fenerbahce 3.35 PAOK FC 2.45 AC Omonia Nicosia 5.00 Sporting CP 15.5 Besiktas 3.65 AEK Athens FC 16.5 Anorthosis Famagusta FC 5.00 FC Famalicao 33.0 Basaksehir FK 12.0 Aris Thessaloniki FC 250 Apollon Limassol FC 6.00 Sporting Braga 140 Trabzonspor 16.5 AO Xanthi FC 260 AEK Larnaca FC 10.0 Vitoria Guimaraes 360 Alanyaspor 62.0 Panathinaikos Athens 340 AEL Limassol FC 67.0 Holland Eredivisie 2019/20 Germany Bundesliga 2019/20 Russia Premier Liga 2019/20 Switzerland Super League 2019/20 Runners Winner Runners Winner Runners Winner Runners Winner Ajax Amsterdam 1.55 FC Bayern Munich 1.22 FC Zenit St Petersburg 1.75 BSC Young Boys 1.85 PSV Eindhoven 2.25 Borussia Dortmund 7.50 CSKA Moscow 5.30 FC Basel 1893 1.85 AZ Alkmaar 33.0 RB Leipzig 10.3 FC Krasnodar 5.30 FC Sion 86.0 Vitesse Arnhem 36.0 Bayer 04 Leverkusen 58.0 FC Lokomotiv Moscow 6.00 FC St. -

SAS Ligaen 4. Runde SØNDAG DEN 15. AUGUST KL. 17.30 I PARKEN

SAS Ligaen 4. runde BYENS HOLD F.C. København fredag den 13. august 2004 | Kampprogram nr. 199 | til søndagens kamp i SAS Ligaen mod Odense Boldklub | www.fck.dk ”Vi har brug for en kanon opbakning på søndag!” Lars Jacobsen F.C. København – OB SØNDAG DEN 15. AUGUST KL. 17.30 I PARKEN NB: Portene åbnes kl. 16.30 ’’Vi skal stå sammen’’ [Interview med anfører Bo Svensson] Hvordan havde spillerne det Det har været en hård uge for Vi har spillet mange gode kampe i de sidste dagen efter kampen mod Københavns fans og alle tre år, og vi ved, at vi nu har et hold, som kan Gorica? involverede i klubben. spille god fodbold, og det er bare et spørgs- Man kunne mærke en enorm frustration i Hvordan har spillerne tacklet mål om tid, før selvtilliden kommer tilbage. hele truppen, fordi vi vidste, at vi kunne spil- kritikken af holdet efter sid- Sidste uge var vi måske stadigvæk lidt "men- le meget bedre, end det vi viste, og det var ste uges nederlag? talt skrøbelige" fire dage efter nederlaget i svært for os alle at forklare, hvad der skete i Det har selvfølgelig ikke været så sjovt at PARKEN, men vi kan forhåbentlig allerede på de 90 minutter. læse al kritikken af holdet, men man skal søndag mod OB komme på rette spor. huske at for to måneder siden modtog vi Spillerne er selvfølgelig klar over, at det er ikke andet end positiv kritik og medierne Hvad vil du sige til vores vores skyld, at vi tabte kampen, det er os der havde kun ros til os.Vi er godt klar over, at vi fans? har underpræsteret, og vi har ingen und- på mange måder har fortjent den negative I Viborg i sidste uge fik holdet en fantastisk skyldning. -

Danish Dynamite: the Story of Football’S Greatest Cult Team

To Sepp and the boys of 86, who made football fun Contents 1 Mr and Mrs Bignell 2 For he’s a jolly good fellow 3 Alemano Bruto 4 Concrete illness 5 De Vlo effect 6 Twin towers 7 The sparrow and the shadow 8 The roligans 9 ‘If I had a gun …’ 10 The first time 11 Poster boys 12 ‘The game’ 13 Gloria Dana 14 ‘Re-Sepp-Ten’ 15 For Denmark 16 A public fiesta of football 17 Pyrrhic victory 18 The worst time 19 The binary boys 20 Glory 21 When we should have been world champions Bibliography Acknowledgements List of Illustrations Chapter 1 Mr and Mrs Bignell In the 2010s Denmark became one of the world’s most fashionable countries. There were myriad reasons for this, from Nordic noir to gastronomy via architecture, craft beer and even knitwear. Football fans of a certain age wondered what took everyone else so long to discover this. In the mid- 1980s, Denmark were the most interesting and perhaps the best football team in the world, an almost unprecedented achievement for a country with a population of only five million. ‘What Denmark did was amazing,’ said Diego Maradona. ‘They were like a bullet train.’ They made history by playing football from the future: a fast-forward version of the Dutch Total Football that had charmed the world in the 1970s, and with the same unashamedly attacking intent. Denmark’s style made children fall in love with football and reminded adults why they had fallen in love with it in the first place. -

Caribbean Teams in North American Professional Soccer: Time for a New Direction?

Caribbean Teams in North American Professional Soccer: Time for a New Direction? Glen ME Duerr Department of History and Government Cedarville University 104 HRS, 251 N. Main Street Cedarville, Ohio, USA 45314 [email protected] RASAALA, Vol. 5, No. 1 (2014) 1 Caribbean Teams in North American Professional Soccer: Time for a New Direction? Abstract This paper examines the interrelated issues of time and money in club and international football. Specifically, the focus is on small Caribbean countries and territories that are rich in talent, but poor in opportunities. In the past decade, several professional teams in the Caribbean have played in the minor league system in North America, but have been stifled by several factors. This paper argues that the creation of a ‘Caribbean division’ that plays in either the North American Soccer League (NASL) or United Soccer League (USL)-Pro league would enrich and develop teams and players from all parties involved, and they would be more competitive in FIFA World Cup qualifying. The key ingredient is correctly timing such a venture. Keywords: Caribbean, soccer, North America, USL-Pro, NASL RASAALA, Vol. 5, No. 1 (2014) 2 Introduction Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football (CONCACAF), the regional governing body of soccer in North America, Central America, and the Caribbean, sends three and a half teams to the quadrennial FIFA World Cup. The fourth-placed CONCACAF team plays a home and away playoff series against a team in another region, either in Asia, South America or Oceania, depending on the rotation. On every occasion since the number of berths was expanded to three in 1998, the United States and Mexico have taken two of the berths. -

Scandinavian Women's Football Goes Global – a Cross-National Study Of

Scandinavian women’s football goes global – A cross-national study of sport labour migration as challenge and opportunity for Nordic civil society Project relevance Women‟s football stands out as an important subject for sports studies as well as social sciences for various reasons. First of all women‟s football is an important social phenomenon that has seen steady growth in all Nordic countries.1 Historically, the Scandinavian countries have been pioneers for women‟s football, and today Scandinavia forms a centre for women‟s football globally.2 During the last decades an increasing number of female players from various countries have migrated to Scandinavian football clubs. Secondly the novel development of immigration into Scandinavian women‟s football is an intriguing example of the ways in which processes of globalization, professionalization and commercialization provide new challenges and opportunities for the Nordic civil society model of sports. According to this model sports are organised in local clubs, driven by volunteers, and built on ideals such as contributing to social cohesion in society.3 The question is now whether this civil society model is simply disappearing, or there are interesting lessons to be drawn from the ways in which local football clubs enter the global market, combine voluntarism and professionalism, idealism and commercialism and integrate new groups in the clubs? Thirdly, even if migrant players stay only temporarily in Scandinavian women‟s football clubs, their stay can create new challenges with regard to their integration into Nordic civil society. For participants, fans and politicians alike, sport appears to have an important role to play in the success or failure of the integration of migrant groups.4 Unsuccessful integration of foreign players can lead to xenophobic feelings, where the „foreigner‟ is seen as an intruder that pollutes the close social cohesion on a sports team or in a club. -

A Football Journal by Football Radar Analysts

FFoooottbbaallll RRAADDAARR RROOLLIIGGAANN JJOOUURRNNAALL IISSSSUUEE FFOOUURR a football journal BY football radar analysts X Contents GENERATION 2019: YOUNG PLAYERS 07 Football Radar Analysts profile rising stars from around the globe they tip to make it big in 2019. the visionary of nice 64 New ownership at OGC Nice has resulted in the loss of visionary President Jean-Pierre Rivere. Huddersfield: a new direction 68 Huddersfield Town made the bold decision to close their academy, could it be a good idea? koncept, Kompetenz & kapital 34 Stepping in as Leipzig coach once more, Ralf Rangnick's modern approach again gets results. stabaek's golden generation 20 Struggling Stabaek's heavy focus on youth reaps rewards in Norway's Eliteserien. bruno and gedson 60 FR's Portuguese analysts look at two players named Fernandes making waves in Liga Nos. j.league team of the season 24 The 2018 season proved as unpredictable as ever but which players stood out? Skov: THE DANISH SNIPER 38 A meticulous appraisal of Danish winger Robert Skov's dismantling of the Superligaen. europe's finishing school 43 Belgium's Pro League has a reputation for producing world class talent, who's next? AARON WAN-BISSAKA 50 The Crystal Palace full back is a talented young footballer with an old fashioned attitude. 21 under 21 in ligue 1 74 21 young players to keep an eye on in a league ideally set up for developing youth. milan's next great striker? 54 Milan have a history of legendary forwards, can Patrick Cutrone become one of them? NICOLO BARELLA: ONE TO WATCH 56 Cagliari's midfielder has become crucial for both club and country. -

CAS 2017/O/5264 Miami FC & Kingston Stockade FC V. FIFA

CAS 2017/O/5264 Miami FC & Kingston Stockade FC v. FIFA CAS 2017/O/5265 Miami FC & Kingston Stockade FC v. CONCACAF CAS 2017/O/5266 Miami FC & Kingston Stockade FC v. USSF ARBITRAL AWARD delivered by the COURT OF ARBITRATION FOR SPORT sitting in the following composition: President: Mr Efraim Barak, Attorney-at-Law, Tel Aviv, Israel Arbitrators: Mr J. Félix de Luis y Lorenzo, Attorney-at-Law, Madrid, Spain Mr Jeffrey Mishkin, Attorney-at-Law, New York, USA Ad hoc Clerk: Mr Dennis Koolaard, Attorney-at-Law, Arnhem, the Netherlands in the arbitration between MIAMI FC, Miami, Florida, USA as First Claimant and KINGSTON STOCKADE FC, Kingston, New York, USA as Second Claimant Both represented by Dr. Roberto Dallafior and Mr Simon Bisegger, Attorneys-at-Law, Nater Dallafior Rechtsanwälte AG, Zurich, Switzerland, and Ms Melissa Magliana, Attorney-at-Law, Lalive, Zurich Switzerland and FÉDÉRATION INTERNATIONALE DE FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION (FIFA), Zurich, Switzerland Represented by Mr Antonio Rigozzi, Attorney-at-Law, Lévy Kaufmann-Kohler, Geneva, Switzerland as First Respondent and CAS 2017/O/5264 Miami FC & Kingston Stockade FC v. FIFA CAS 2017/O/5265 Miami FC & Kingston Stockade FC v. CONCACAF CAS 2017/O/5266 Miami FC & Kingston Stockade FC v. USSF Page 2 CONFEDERATION OF NORTH, CENTRAL AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN ASSOCIATION FOOTBALL, INC. (CONCACAF), Nassau, Bahamas Represented by Mr John J. Kuster, Esq., and Mr Samir A. Gandhi, Esq., Sidley Austin LLP, New York, USA as Second Respondent and UNITED STATES SOCCER FEDERATION (USSF), Chicago, Illinois, USA Represented by Mr Russel F. Sauer, Esq., Mr Michael Jaeger, Esq. -

Godkendt Årsrapport for FC Midtjylland 2017/2018

FC Midtjylland A/S Kaj Zartows Vej 5, DK-7400 Herning Årsrapport for 1. juli 2017 - 30. juni 2018 Annual Report for 1 July 2017 - 30 June 2018 CVR-nr. 31 57 61 56 Årsrapporten er fremlagt og godkendt på selskabets ordi- nære generalforsamling den 29/10 2018 The Annual Report was presented and adopted at the Annual General Meeting of the Company on 29/10 2018 Penneo document key: K2L7L-5G3PS-8A3SQ-DBTDV-S2ZEG-E7P0M Albert Kusk Dirigent Chairman of the General Meeting Indholdsfortegnelse Contents Side Page Påtegninger Management’s Statement and Auditor’s Report Ledelsespåtegning 1 Management’s Statement Den uafhængige revisors revisionspåtegning 2 Independent Auditor’s Report Ledelsesberetning Management’s Review Selskabsoplysninger 7 Company Information Hoved- og nøgletal 8 Financial Highlights Ledelsesberetning 10 Management’s Review Årsregnskab Financial Statements Resultatopgørelse 1. juli - 30. juni 25 Income Statement 1 July - 30 June Balance 30. juni 26 Balance Sheet 30 June Egenkapitalopgørelse 30 Statement of Changes in Equity Pengestrømsopgørelse 1. juli - 30. juni 31 Cash Flow Statement 1 July - 30 June Noter til årsregnskabet 33 Penneo document key: K2L7L-5G3PS-8A3SQ-DBTDV-S2ZEG-E7P0M Notes to the Financial Statements Translation of the Danish original. In case of discrepancy, the Danish version shall prevail. Ledelsespåtegning Management’s Statement Bestyrelse og direktion har dags dato behandlet og The Executive Board and Board of Directors have godkendt årsrapporten for regnskabsåret 1. juli 2017 today considered and adopted the Annual Report of - 30. juni 2018 for FC Midtjylland A/S. FC Midtjylland A/S for the financial year 1 July 2017 - 30 June 2018. -

Authorized Betting List A) Basic Rules Concerning the List

Authorized betting list A) Basic Rules concerning the list: - When the qualifications for an event are not mentioned in the list, then betting on the qualifications is not allowed. - Name of the competitions is only mentioned when it differs from the name of the level of the competition. - Regarding events that involve a women’s competition as well as a men’s competition, betting on the women’s competition is only allowed when it is mentioned (under the name of the events or the particularities). - Betting is allowed pre-Match and Live (granted the operator holds a decision allowing it to offer live sports betting).1 - For national championships in the list that involve a relegation group structure, bets are still allowed on the relegation group encounters. - On opposite, bets are not allowed on promotion group play that only involves teams from a division that is not mentioned in the list. - For national championships, Promotion/Relegation encounters where teams from a division mentioned in the list play against the best teams from the division directly inferior to it are allowed. - Bets on encounters in a friendly tournament of football that is not named in this document are allowed if they respect the restrictions stated under football / friendly games / club in the list. - Regarding events where the participants are timed (ex: alpine downhill skiing, mechanical sports, etc.); bets on training runs are never allowed. - Bets on rankings are never allowed except : a) If the ranking itself grants entry to an international Cup (ex : UEFA Europa League in football) b) If the ranking itself grants entry to an international competition mentioned in the list; ex : rankings (depending on which continent a team represents) in the 2019 Basketball World Cup will be decisive for 7 (out of 12) qualificative spots for the 2020 Olympic Tournament. -

Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction

Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction Chazan – Pantzalis Victor SID: 3308170004 SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science DECEMBER 2019 THESSALONIKI – GREECE I Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction Chazan – Pantzalis Victor SID: 3308170004 Supervisor: Prof. Christos Tjortjis Supervising Committee Members: Dr. Stavros Stavrinides Dr. Dimitris Baltatzis SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science DECEMBER 2019 THESSALONIKI – GREECE II Abstract Sports Analytics is not a new idea, but the way it is implemented nowadays have brought a revolution in the way teams, players, coaches, general managers but also reporters, betting agents and simple fans look at statistics and at sports. Machine Learning is also dominating business and even society with its technological innovation during the past years. Various applications with machine learning algorithms on core have offered implementations that make the world go round. Inevitably, Machine Learning is also used in Sports Analytics. Most common applications of machine learning in sports analytics refer to injuries prediction and prevention, player evaluation regarding their potential skills or their market value and team or player performance prediction. The last one is the issue that the present dissertation tries to resolve. This dissertation is the final part of the MSc in Data Science, offered by International Hellenic University. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Supervisor, Professor Christos Tjortjis, for offering his valuable help, by establishing the guidelines of the project, making essential comments and providing efficient suggestions to issues that emerged. -

Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011

Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 A Project Funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme Jean Williams Senior Research Fellow International Centre for Sports History and Culture De Montfort University Contents: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011 Contents Page i Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Introduction: Women’s Football and Europe 1 1.1 Post-war Europes 1 1.2 UEFA & European competitions 11 1.3 Conclusion 25 References 27 Chapter Two: Sources and Methods 36 2.1 Perceptions of a Global Game 36 2.2 Methods and Sources 43 References 47 Chapter Three: Micro, Meso, Macro Professionalism 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Micro Professionalism: Pioneering individuals 53 3.3 Meso Professionalism: Growing Internationalism 64 3.4 Macro Professionalism: Women's Champions League 70 3.5 Conclusion: From Germany 2011 to Canada 2015 81 References 86 i Conclusion 90 4.1 Conclusion 90 References 105 Recommendations 109 Appendix 1 Key Dates of European Union 112 Appendix 2 Key Dates for European football 116 Appendix 3 Summary A-Y by national association 122 Bibliography 158 ii Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 Abbreviations and Acronyms AFC Asian Football Confederation AIAW Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women ALFA Asian Ladies Football Association CAF Confédération Africaine de Football CFA People’s Republic of China Football Association China ’91 FIFA Women’s World Championship 1991 CONCACAF Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football CONMEBOL -

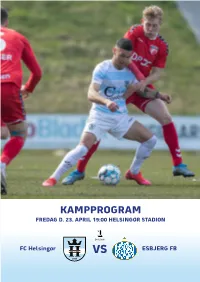

Kampprogram Fredag D

KAMPPROGRAM FREDAG D. 23. APRIL 19:00 HELSINGØR STADION FC Helsingør VS ESBJERG FB Erhvervs Partner LOKAL TOLK Murermester Egon Geertsen Helsingør Golf Club Krone Partner Tribune Partner Hovedsponsor Guld Partner Sølv Partner 3000 Partner Ajour Nordsjællands Brandskole Fredensborg Vinimport ApS Næsby - Den Søde Bager Helsingør Ventilation Oasen Kebab Mama Rosa Popcornmanden.dk Rib house Ralphs Cykler Baktotal Restaurant Strandborg Trolle Company Rico Mens Wear 12’er Pubben Riva Pizza & Steak House 360 Business Tool MP Enterprise Blomsterhjørnet Nordsjællands Proviant Landinspektørkontoret Kamppartner Kampboldpartner TRÆNERE Morten Eskesen Mikkel Thygesen ANGREB 77 10 8 Lucas Haren Jeppe Kjær Callum McCowatt 98 12 Liam Jordan Sebastian Czajkowski MIDTBANE 30 2 42 Tonni Adamsen Nicklas Mihkel Ainsalu Mouritsen 21 11 88 Carl Lange David Boysen Daniel Norouzi 7 27 17 Anders Holst Elijah Just Oliver Kjærgaard 23 19 28 Frederik Matias Philip Rejnhold Christensen Christensen FORSVAR 33 6 3 Hans Bonnesen Nikolaj Hansen Frederik Bay 20 25 Jonas Henriksen Dalton Wilkins 14 5 Nicolai Geertsen Brandon Onkony MÅLMÆND 31 97 1 Frederik Christoffer Kevin Stuhr Rosenqvist Petersen Ellegaard Tøj Partner Vi har virkelig glædet Begge vores to tidligere kampe mod Esbjerg har været underholdende. I os til at være sammen Esbjerg var der både flotte mål, et med jer tilskuere straffespark, en udvisning og generelt flot spil fra begge hold. På Tilskuere på stadion er den bedste hjemmebane var det et tæt opgør hvor nyhed vi har fået i 2021. Vi har virkelig Esbjerg var lidt skarpere på dagen set frem til denne dag hvor vi i end vi var. Esbjerg har kæmpet om fællesskab kan opleve en oprykning til superligaen fra runde 1 fodboldkamp sammen.