"Pilgrimage to Lomza"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lithuanian Synagogues: from the First Descriptions to Systematic Research

arts Article Lithuanian Synagogues: From the First Descriptions to Systematic Research Vilma Gradinskaite Independent scholar, 05224 Vilnius, Lithuania; [email protected] Received: 4 March 2020; Accepted: 15 May 2020; Published: 21 May 2020 Abstract: The article presents an analysis of the development stages of synagogue research methodology in Lithuania during the four major historical periods of the country—Lithuania in the Russian Empire (1795–1918), Vilnius Region in the interwar period and the independent Republic of Lithuania (1918–1940), the Soviet period (1940–1990), and the independent Republic of Lithuania restored in 1990. Each chapter of the article deals with the issues of synagogue research, heritage conservation and management, while the part about the restored independent Republic of Lithuania and modern days includes topical issues related to synagogue restoration, commemoration and putting them into operation. The study uses two different sources: archival materials and publications. Written sources and publications are reviewed in chronological order and start from the end of the 18th century. The study employs several research methods—the historical descriptive method, the comparative method and the analysis method. Keywords: Lithuania; synagogues; conservation; restoration; renovation; rebuilding; management; commemoration 1. Introduction The article presents several fields of study: (1) a review of the first descriptions of synagogues in Lithuania; (2) an analysis of the development stages of synagogue research methodology in Lithuania; and (3) a brief reference to synagogue restoration, renovation, rebuilding, commemoration and putting into operation—topics which are currently particularly live in Lithuania today. It is not possible to understand the existing trends in synagogue research in Lithuania without considering the country’s past—the times of the Russian Empire, the interwar period and the Soviet period. -

VILNIUS Low Vacancy Drives Office Preleasing and Construction Activity

LITHUANIA VILNIUS Low vacancy drives office preleasing and construction activity NET 100 OFFICE € RENT RATE % A RECORD LEVEL OF TAKE-UP icant was the Lithuania’s first tech uni- 90 ABSORPTION 80 PRIME RENT 193 6 SUPPORTS ACTIVE DEVELOPMENT corn Vinted who decided to relocate and 70 thousands & VACANCY 192 5 By the end of 2019, the stock of mod- signed 9,000 sqm in Uptown Park. Low 60 +143% of sqm 50 RATE 40 191 -30bp 4 ern office premises in Vilnius totalled vacancy is likely to remain as most of 30 724,100 sqm and the vacancy rate re- these transctions are pre-let. 20 190 3 10 mains among the lowest in the Baltics. 0 Around 300,000 sqm of new supply is INCREASED FOREIGN INVESTOR 2016 2017 2018 2019 2016 2017 2018 2019 under construction to meet improved CONFIDENCE IN THE OFFICE MARKET % BOND YIELD PRIME YIELD % demand. The record level of new lease In 2019, the total investment volume in 331 OFFICE OFFICE transactions at 115,000 sqm in 2019 sig- Lithuania was €436m, which is the high- 0.4 7.0 INVESTMENT PRIME nals increasing demand for high quality est ever recorded. Investors focused most 165 0.3 6.5 € million 130 +101% YIELD newly developed space. Net absorption money at the capital city Vilnius with a 0.2 -45bp 6.0 69 & BOND remains positive indicating that the smaller share of capital allocated to the YIELD 0.1 5.5 market remains attractive to newcomers second city Kaunas. The office segment as well as existing tenants. -

Baltic Treasures Itinerary: Vilnius

BALTIC TREASURES ITINERARY: VILNIUS- TRAKAI -HILL OF CROSSES-RUNDALE-RIGA–SIGULDA-PARNU- SAAREMAA-KURRESAARE-HAAPSALU-TALLINN DURATION: 9 days / 8 nights Day 1 Vilnius Arrival in Vilnius, the capital city of Lithuania Transfer from the airport to the hotel Check in at the hotel Overnight in Vilnius Day 2 Vilnius – Trakai Breakfast at the hotel. Vilnius city tour 3h Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania was founded in 1323 when Grand Duke Gediminas built a castle there, nowadays bustling city with one of the oldest and most charming Old Towns in Europe. The splendid architectural blend of Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque styles makes this a wonderful city to explore. During sightseeing tour you will visit Old town, which is included to the UNESCO World Heritage. Visit Cathedral and Cathedral Square and pass by Gediminas Avenue, the Parliament and President's Palace, Vilnius University and Town Hall. Continue walking narrow old streets, visit St. Anna's Church - a gem of Gothic architecture, Gates of Dawn and St. Peter-Paul Church. Further way to Trakai. Visiting Trakai castle 2h Trakai, the former capital of Lithuania, which is situated on an island in the middle of a lake. The 14th century red brick castle now houses the Art Museum. The castles of Trakai are the best known works of defensive architecture in Lithuania. The old town of Trakai, which includes the Island and the Peninsula Castles, surrounded by lakes, is one of the most impressive and most picturesque locations in Europe. Here still reside small national minority of Karaites, which is confessing Judaism. It is believed they were brought from the Crimea by the Grand Lithuanian Duke Vytautas. -

The Prague Summit and Nato's Transformation

THE PRAGUE SUMMIT AND NATO’S TRANSFORMATION NATO PUBLIC DIPLOMACY DIVISION 1110 Brussels - Belgium Web site: www.nato.int E-mail: [email protected] A READER’S GUIDE THE PRAGUE SUMMIT AND NATO’S TRANSFORMATION SUMMIT AND NATO’S THE PRAGUE PRARGENG0403 A READER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 I THE SUMMIT DECISIONS 9 II KEY ISSUES 19 New members: Expanding the zone of security 20 New capabilities: Adapting to modern challenges 26 New relationships: Practical cooperation and dialogue 34 After Prague: The road ahead 67 © NATO 2003 NATO INVITEES Country* Capital Population GDP Defence Active Troop *Data based on (million) (billion expenditures Strength national sources Euros) (million Euros) Bulgaria (25) Sofia 7.8 16.9 494 (2.9% GDP) 52 630 Estonia (27) Tallin 1.4 6.8 130 (1.9% GDP) 4 783 Latvia (33) Riga 2.3 8.8 156 (1.8% GDP) 9 526 Lithuania (34) Vilnius 3.5 14.5 290 (2.0% GDP) 17 474 Romania (36) Bucharest 22.3 47.9 1117 (2.3% GDP) 99 674 Slovakia (38) Bratislava 5.4 24.9 493 (2.0% GDP) 29 071 ★ Slovenia (39) Ljubljana 2.0 22.4 344 (1.5% GDP) 7 927 III DOCUMENTATION 71 Prague Summit Declaration – 21 November 2002 72 Prague Summit Statement on Iraq – 21 November 2002 78 Announcement on Enlargement – 21 November 2002 79 Report on the Comprehensive Review of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council and Partnership for Peace - 21 November 2002 80 Partnership Action Plan Against Terrorism - 21 November 2002 87 Chairman’s Summary of the Meeting of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council at Summit Level – 22 November 2002 94 Statement by NATO -

United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

Case: 1:16-cv-04868 Document #: 126 Filed: 03/09/18 Page 1 of 13 PageID #:<pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION NERINGA PUMPUTYTE, on behalf of herself and all ) others similarly situated, ) ) 16 C 4868 Plaintiff, ) ) Judge Gary Feinerman vs. ) ) UNITED AIRLINES, INC., ) ) Defendant. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Lilija Pumputiena brought this suit on behalf of herself, her then-minor child Neringa Pumputyte, and four putative classes against Deutsche Lufthansa and United Airlines, alleging breach of contract and violation of the Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules for International Carriage by Air (“Montreal Convention”) in connection with a June 2015 flight on United from Chicago, Illinois to Brussels, Belgium, and ensuing travel on Lufthansa from Brussels to Vilnius, Lithuania. Doc. 7. The court dismissed all claims against Lufthansa and some claims against United. Docs. 37-38 (reported at 2017 WL 66823 (N.D. Ill. Jan. 6, 2017)). Pumputiena filed an amended complaint, Doc. 43, and after United argued that the amendment contravened the dismissal order, Doc. 45, Pumputyte, no longer a minor and proceeding in her own name, filed a second amended complaint. Doc. 48. United then filed a motion to dismiss and to strike parts of the second amended complaint, Doc. 50, which the court granted in part and denied in part, Docs. 70-71 (reported at 2017 WL 2243095 (N.D. Ill. May 23, 2017)). United now moves for summary judgment on the remaining claims. Doc. 87. While that motion was pending, Pumputyte moved for class certification on one of those claims. -

From "Russian" to "Polish": Vilna-Wilno 1900-1925

FROM “RUSSIAN” TO “POLISH”: Vilna-Wilno 1900-1925 Theodore R. Weeks Southern Illinois University at Carbondale The National Council for Eurasian and East European Research 910 17th Street, N.W. Suite 300 Washington, D.C. 20006 TITLE VIII PROGRAM Project Information* Principal Investigator: Theodore R. Weeks Council Contract Number: 819-06g Date: June 4, 2004 Copyright Information Scholars retain the copyright on works they submit to NCEEER. However, NCEEER possesses the right to duplicate and disseminate such products, in written and electronic form, as follows: (a) for its internal use; (b) to the U.S. Government for its internal use or for dissemination to officials of foreign governments; and (c) for dissemination in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the U.S. government that grants the public access to documents held by the U.S. government. Additionally, NCEEER has a royalty-free license to distribute and disseminate papers submitted under the terms of its agreements to the general public, in furtherance of academic research, scholarship, and the advancement of general knowledge, on a non-profit basis. All papers distributed or disseminated shall bear notice of copyright. Neither NCEEER, nor the U.S. Government, nor any recipient of a Contract product may use it for commercial sale. * The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract or grant funds provided by the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, funds which were made available by the U.S. Department of State under Title VIII (The Soviet-East European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended). -

Berlin to the Baltics: Germany, Czech Republic, Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Finland

FIND OUT MORE! www.ecetravelsptpi.com 2017 TRAVEL BERLIN TO THE BALTICS: GERMANY, CZECH REPUBLIC, POLAND, ESTONIA, LATVIA, LITHUANIA AND FINLAND Your key destinations: Berlin, Prague, ADVENTURE Challenge yourself and experience Krakow, Warsaw, Vilnius, Riga, personal growth as you: Tallinn and Helsinki. • Navigate the challenges of Tallinn’s premier ‘Rope Garden’ Explore a wealth of Eastern • Explore Helsinki by bike during an exclusive People to People moment European history, stretching • Explore Finland’s thrilling amusement park, Linnanmaki from the Medieval castles of the Baltics to war torn Berlin. EDUCATION Learn about different cultures and Discover how WW2 and the traditions as you: • Pay your respects at Auschwitz Cold War have shaped the • Attend an insightful, specially arranged meeting with a witness to the fall of the Berlin Wall region, as well as the ancient • Challenge the body and mind with sporting competitions and classical music performances traditions of the countries that make up this beautiful part of CULTURE Connect with locals as you: the world. • Immerse yourself in the glorious architecture of the region, particularly the much heralded city of Dresden All-inclusive Program Price: $6,290 • Meet like-minded peers and create long-lasting international relationships • With the help of experts, examine the progression of European society during the Cold *Supplements may apply. War and beyond 2017 TRAVEL BERLIN TO THE BALTICS: ITINERARY Helsinki GERMANY, CZECH REPUBLIC, POLAND, ESTONIA, LATVIA, LITHUANIA AND FINLAND Tallinn Day 7 Riga Day 1 Explore the sights of Krakow Depart the USA Join a guided visit of the Wawel Castle, a Vilnius Board your overnight flight to Europe. -

Amsterdam Has No Lack of Collaborative, Creative Start-Ups

Festival in Varadzin- akovec in Croatia The shopping district of Vilnius in Lithuania WIKIMEDIA.COM GETTY IMAGES t the Wibaut Building, Willem van Winden of- fers his apologies when the reserved space turns out to be occupied by hard-working students. It Urban is rush hour at the AUAS Abuilding – there is no free space available anywhere for a conversation about the ABCitiEs project, a four-year European research project into the ways in which city governments deal with collaborative initia- research tives of residents, employers, social organi- sations, and knowledge institutes. There is, however, space available outside, on a bench behind the faculty building, sheltered from busy arterial roads like Wibautstraat Amsterdam has no lack of collaborative, creative and Mauritskade. The bicycle caretakers of the AUAS keep the small square free from start-ups, employers’ associations, and residents’ scooters and bicycles, to the enjoyment of initiatives. How does the municipal government users and hospitality establishments alike. It is a fine example of a neighbourhood initia- deal with them? Over the next four years, the tive from the bottom up, in which the munici pality plays no part. Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences (AUAS) ‘This is a good example of new parties will be heading a major European research project within the city seeking out collaborations that allow them to take the lead,’ Van to study how local governments can best support Winden points out. ‘The classic example of these types of initiatives. A conversation with this type of collaboration is the shopkeep- ers’ association in a shopping street, where urban economist Willem van Winden. -

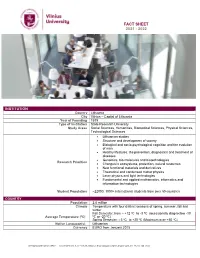

Fact Sheet 2021 - 2022

FACT SHEET 2021 - 2022 INSTITUTION Country Lithuania City Vilnius – Capital of Lithuania Year of Founding 1579 Type of Institution State Research University Study Areas Social Sciences, Humanities, Biomedical Sciences, Physical Sciences, Technological Sciences • Lithuanian studies • Structure and development of society • Biological and socio-psychological cognition and the evolution of man • Healthy lifestyles, the prevention, diagnostics and treatment of diseases • Genomics, bio molecules and biotechnologies Research Priorities • Changes in ecosystems, protection, natural resources • New functional materials and derivatives • Theoretical and condensed matter physics • Laser physics and light technologies • Fundamental and applied mathematics, informatics and information technologies Student Population ~22000. 1000+ international students from over 50 countries COUNTRY Population 2,8 million Climate Temperature with four distinct seasons of spring, summer, fall and winter Fall Semester: from – +12 0C to -3 0C (occasionally drop below -10 Average Temperature (0C) 0C or -20 0C) Spring Semester: - 3 0C to +20 0C (Maximum over +30 0C) Native Language(s) Lithuanian Currency EURO from January 2015 International Relations Office. Universiteto str. 3, LT – 01513, Vilnius, Lithuaniawww.vu.lt/en, [email protected] , tel. +370 5 268 7250 INFORMATION ABOUT EXCHANGE STUDIES Office in Charge of Students Exchange International Relations Office Information for Exchange Students http://www.vu.lt/en/studies/exchange-students Application* deadlines: ONLY Online-application acceptable: http://www.vu.lt/en/studies/exchange-students/enrolment-procedure Fall semester June 1st th Spring Semester November 15 Mentor programme http://www.vu.lt/en/studies/practical-information/56-studies/studies/2504 Orientation Week Support Programmes The Orientation week takes place at the beginning of each semester. -

Gentrification in Vilnius (Lithuania): the Example of Uzupis Standl, Harald; Krupickaitė, Dovilė

www.ssoar.info Gentrification in Vilnius (Lithuania): the example of Uzupis Standl, Harald; Krupickaitė, Dovilė Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Standl, H., & Krupickaitė, D. (2004). Gentrification in Vilnius (Lithuania): the example of Uzupis. Europa Regional, 12.2004(1), 42-51. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-48092-5 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. Gentrification in Vilnius (Lithuania) – the example of Užupis . -

COMMISIONS 2017, Art Dubai, Dubai, UAE — DO DISTURB, Palais De T

Eglė Budvytytė SELECTED PERFFORMANCES, EXHIBITIONS, FESTIVALS Reguliersgracht 45 2017 1017LK Amsterdam — COMMISIONS 2017, Art Dubai, Dubai, UAE The Netherlands — DO DISTURB, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France — BLOCK UNIVERSE, performance festival, London, UK [email protected] — LOFOTEN INTERNATIONAL ART FESTIVAL, Lofoten islands, Norway +31 614635171 — LITTLE REBELLIONS, European capital of culture, Aarhus, Denmark www.eglebudvytyte.lt — SOLO show, Album arte, Rome, Italy — PUBLIC MOVEMENT, Moderna Museet, Malmo, Sweden EDUCATION 2016 2006–2008 — SKATEBOARD PRAYER, OR HEAD BELOW THE HEART, CAC, Vilnius, Lithuania MA in Fine Arts, Piet Zwart Institute, — FOREIGN PLACES, WIELS, Brussels, Belgium The Netherlands — IDENTITY. BEHIND THE CURTAIN OF UNCERTAINTY, National art museum of 2004–2006 Ukraine, Kiev, Ukraine BA in Audio-Visual, Gerrit Rietveld — CLIMBING INVISIBLE STRUCTURES, Nida Art Collony, Nida, Lithuania Academie, The Netherlands 2000–2004 BA in Photography, Vilnius Art Academy, 2015 Lithuania — ACCA in the City, ACCA, Melbourne, Australia — Survival kit, Latvian centre for contemporary art, Riga, Latvia RESIDENCIES — 11th Performance Project by the LISTE, Art Fair Basel, Switzerland — FRASCATTI ISSUES: MR. MRS. MX., Frascatti theater, Amsterdam, 2015 The Netherlands Office for Contemporary Art Norway, — ARTEFACT FESTIVAL, STUK Art Centre, Leuven, Belgium OCA, Oslo, Norway — SCULPTURE INTERNATIONAL ROTTERDAM, Rotterdam, The Netherlands 2013 Wiels, Wiels Art Center, Brussels, Belgium 2014 2011 — PRESENT TENSE, Kalmar Museum, -

Ipbib Vilnius 2011 Third Project Year

ERASMUS Intensive Programme „Das Grimm-Zentrum - (k)ein Bibliotheksmärchen“ IPBib Vilnius 2011 Third Project Year Project Documentation ERASMUS Intensive Programme „Das Grimm-Zentrum - (k)ein Bibliotheksmärchen“ IPBib Vilnius 2011 Third Project Year Project Documentation Editorial Contents Publisher: University Library of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Foreword ..................................................... 4 Institute for Library and Information Science (IBI) 1. Project Description IPBib Vilnius 2011 ..... 6 Editors: Gertrud Pannier, Katharina Tollkühn 2. Participants ............................................. 8 Texts: Anna Lukasek, Oliver Pohl, Ulrike Stöckel, 3. Organisation, Itinerary and Contributions 10 Katharina Tollkühn, Katharina Ventzke, Heike Wilhelm 4. Library Visits ............................................ 20 5. Project Management and Evaluation ...... 23 Photos: IPBib-project participants 6. Cultural Activities ................................... 36 7. Project Dissemination ............................ 38 Layout: Anna Lukasek 8. Conclusion and Outlook ......................... 40 Print: Print Office of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Thanks .......................................................... 42 Grant Agreement Reference Number: DE-2011-ERA/MOBIP-3-29975-2-18 Appendices ..................................................... 43 © University Library of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institute for Library and Information Science (IBI) 2011 FOREWORD FOREWORD Foreword Partnership for the future The third and