Translating Burns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Thomas Overbury -- My 10Th Great-Uncle Brother of My 9Th Great-Grandfather Sir Giles Overbury - by David Arthur

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Overbury Sir Thomas Overbury -- My 10th Great-Uncle Brother of My 9th Great-Grandfather Sir Giles Overbury - by David Arthur Sir Thomas Overbury (baptized 1581 – 14 September 1613) was an English poet and essayist, also known for being the victim of a murder which led to a scandalous trial. His poem A Wife (also referred to as The Wife), which depicted the virtues that a young man should demand of a woman, played a large role in the events that precipitated his murder. http://www.edavidarthur.net/Quotes.htm Quotes attributed to Sir Thomas Overby Background Thomas Overbury was the son of Mary Palmer and Nicholas Overbury, of Bourton-on-the-Hill, Gloucester. He was born at Compton Scorpion, near Ilmington, in Warwickshire. In the autumn of 1595, he became a gentleman commoner of Queen's College, Oxford, took his degree of BA in 1598 and came to London to study law in the Middle Temple. He soon found favour with Sir Robert Cecil, travelled on the Continent and began to enjoy a reputation for an accomplished mind and free manners. Robert Carr About 1601, whilst on holiday in Edinburgh, he met Robert Carr, then an obscure page to the Earl of Dunbar. A great friendship was struck up between the two youths, and they came up to London together. The early history of Carr remains obscure, and it is probable that Overbury secured an introduction to court before his young associate contrived to do so. At all events, when Carr attracted the attention of James I in 1606 by breaking his leg in the tilt-yard, Overbury had for some time been servitor-in-ordinary to the king. -

The Early Career of Thomas Craig, Advocate

Finlay, J. (2004) The early career of Thomas Craig, advocate. Edinburgh Law Review, 8 (3). pp. 298-328. ISSN 1364-9809 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/37849/ Deposited on: 02 April 2012 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk EdinLR Vol 8 pp 298-328 The Early Career of Thomas Craig, Advocate John Finlay* Analysis of the clients of the advocate and jurist Thomas Craig of Riccarton in a formative period of his practice as an advocate can be valuable in demonstrating the dynamics of a career that was to be noteworthy not only in Scottish but in international terms. However, it raises the question of whether Craig’s undoubted reputation as a writer has led to a misleading assessment of his prominence as an advocate in the legal profession of his day. A. INTRODUCTION Thomas Craig (c 1538–1608) is best known to posterity as the author of Jus Feudale and as a commissioner appointed by James VI in 1604 to discuss the possi- bility of a union of laws between England and Scotland.1 Following from the latter enterprise, he was the author of De Hominio (published in 1695 as Scotland”s * Lecturer in Law, University of Glasgow. The research required to complete this article was made possible by an award under the research leave scheme of the Arts and Humanities Research Board and the author is very grateful for this support. He also wishes to thank Dr Sharon Adams, Mr John H Ballantyne, Dr Julian Goodare and Mr W D H Sellar for comments on drafts of this article, the anonymous reviewer for the Edinburgh Law Review, and also the members of the Scottish Legal History Group to whom an early version of this paper was presented in October 2003. -

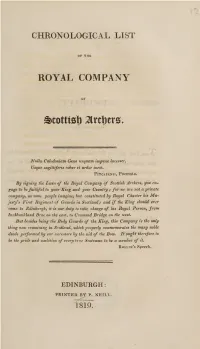

Chronological List of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF THE ROYAL COMPANY OF 2lrrt)er0. Nulla Caledoniam Gens unquarn impune laces set, Usque sagittiferis rohur et ardor inest. Pitcairnii, Poemata. By signing the Laws of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers, you en¬ gage to he faithful to your King and your Country ; for we are not a private company, as some people imagine, but constituted hy Royal Charter his Ma¬ jesty's First Regiment of Guards in Scotland; and if the King should ever come to Edinburgh, it is our duty to take charge of his Royal Person, from Inchbunkland Brae on the east, to Cramond Bridge on the west. But besides being the Body Guards of the King, this Company is the only thing now remaining in Scotland, which properly commemorates the many noble deeds performed by our ancestors by the aid of the Bow. It ought therefore to be the pride and ambition of every true Scotsman to be a member of it. Roslin’s Speech. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY P. NEII.T.. 1819. PREFACE, T he first part of the following List, is not preserved in the handwriting of the Members themselves, and is not accurate with respect to dates; but the names are copied from the oldest Minute-books of the Company which have been preserved. The list from the 13th of May 1714, is copied from the Parchment Roll, which every Member subscribes with his own hand, in presence of the Council of the Company, when he receives his Diploma. Edinburgh, 1 5th July 1819* | f I LIST OF MEMBERS ADMITTED INTO THE ROYAL COMPANY OF SCOTTISH ARCHERS, FROM 1676, Extracted from Minute-books prior to the 13th of May 1714. -

American Clan Gregor Society INCORPORATED

YEAR BOOK OF THE American Clan Gregor Society INCORPORATED Containing the Proceedings of the 1954 Annual Gathering .. THE AMERICAN CLAN GREGOR SOCIETY INCORPORATED WASHIN GTO N, D. C. • Copyright, 1955 by T homas Gar land Magruder, ] r., Editor Cusson s, May & Co., Inc., Printers, Richmond, Va OFFI C ER S SIR MALCOLM MACGREGOR OF M ACGREGOR, BARONET ....H ereditary Chief "Edinchip," Lochearnhead, Scotland BRIG . GEN. MARSHALL MAGRUD ER, U. S. ARMY, Re tired Chieftain 106 Camden Road , N. E. , Atlanta, Ga. F ORREST S HEPPERSON H OL M ES Assistant to the Chieftain .. 6917 Carle ton Terrac e, College P ark. Md . R EV. D ANIEL RANDALL MAGRUDER Rallking D eputy Chieftain Hingham, Mass. M ISS A NNA L OUI SE R EyNOLD S Scribe 5524 8t h St., N . W ., W ashington , D. C. MRS. O . O. VANDEN B ERG........ .......................................... .....••..•R egistrar Th e H ighland s, A pt. 803, W ashington 9, D. C. MISS R EGINA MAGRUDER HILL...... .. .......•................ ........ ............Historian The H ighl and s, Apt. 803, W ashi ngton 9, D. C. C LARE N CE WILLIAM rVICCORM ICK Treasurer 4316 Clagett Road, University Pa rk, Md. R EV. REUEL L AMP HIER HOWE Chaplain Theological Se minary, Alexandria, Va, D R. R OGER GREGORY MAGRUDER Surgeon Lewis Mount ain Circle, Charl ott esville, Va, T HOMAS GARLAND MAGRUDER, J R E ditor 2053 Wil son Boulevard , Arlington, Va . C. VIRGI NIA DIEDEL Chancellor Th e Marlboro A pts., 917 18th St., N . W., Washington 6, D. C. MRS. J A M ES E . ALLGEYER (COLMA M Y ER S ) Deputy S cribe 407 Const itutio n Ave., N. -

Van Heijnsbergen, T. (2013) Coteries, Commendatory Verse and Jacobean Poetics: William Fowler's Triumphs of Petrarke and Its Castalian Circles

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten: Publications Van Heijnsbergen, T. (2013) Coteries, commendatory verse and Jacobean poetics: William Fowler's triumphs of Petrarke and its Castalian circles. In: Parkinson, D.J. (ed.) James VI and I, Literature and Scotland: Tides of Change, 1567-1625. Peeters Publishers, Leuven, Belgium, pp. 45- 63. ISBN 9789042926912 Copyright © 2013 Peeters Publishers A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/69695/ Deposited on: 23 September 2013 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk James VI and I, Literature and Scotland Tides of Change, 1567-1625 EDITED BY David J. Parkinson PEETERS LEUVEN - PARIS - WALPOLE, MA 2013 CONTENTS Plates vii Abbreviations vii Note on Orthography, Dates and Currency vii Preface and Acknowledgements ix Introduction David J. Parkinson xi Contributors xv Shifts and Continuities in the Scottish Royal Court, 1580-1603 Amy L. Juhala 1 Italian Influences at the Court of James VI: The Case of William Fowler Alessandra Petrina 27 Coteries, Commendatory Verse and Jacobean Poetics: William Fowler's Trivmphs of Petrarke and its Castalian Circles Theo van Heijnsbergen 45 The Maitland -

The Swiss School of Church Reformers, and Its Propagation

Chapter II – The Swiss School of Church Reformers, and Its Propagation. Switzerland. As Luther stands unrivalled in the group of worthies who conducted what is termed the Saxon Reformation, Zwingli’s figure is originally foremost in the kindred struggles of the Swiss. He was born* on New Year’s day, 1484, and was thus Luther’s junior only by seven weeks. His father was the leading man of Wildhaus, a parish in the Toggenburg, where, high above the level of the lake of Zürich, he retained the simple dignity and truthfulness that characterized the Swiss of olden times, before they were so commonly attracted from their native pastures to decide the battles of adjacent states.** Huldreich Zwingli, being destined for the priesthood, sought his elementary education at Basel and Bern, and after studying philosophy for two years at the university of Vienna, commenced his theological course at Basel under the care of Thomas Wyttenbach, a teacher justly held in very high repute.*** At the early age of twenty-two, Zwingli was appointed priest of Glarus (1506). He carried with him into his seclusion a passionate love of letters, and especially of that untrodden field of literature which was exciting the profoundest admiration of the age, – the classical remains of Greece and Rome. To these he long devoted his chief interest; for although he was not unacquainted with the writings of the Middle Ages, scholasticism had never any charm for him, and exercised but little influence on his mental training. Thus while Luther undervalued the wisdom of the heathen poets and philosophers, Zwingli venerated them as gifted with an almost supernatural inspiration.*4 *[On the boyhood and early training of Zwingli, see Schuler’s Huldreich Zwingli, Zürich, 1819. -

A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2009-05-01 A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L) Gary P. Gillum [email protected] Susan Wheelwright O'Connor Alexa Hysi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gillum, Gary P.; O'Connor, Susan Wheelwright; and Hysi, Alexa, "A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)" (2009). Faculty Publications. 12. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/12 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 833 FAIRFAX, JOHN, 1623-1700. Rare 922.542 St62f 1681 Presbýteros diples times axios, or, The true dignity of St. Paul's elder, exemplified in the life of that reverend, holy, zealous, and faithful servant, and minister of Jesus Christ Mr. Owne Stockton ... : with a collection of his observations, experiences and evidences recorded by his own hand : to which is added his funeral sermon / by John Fairfax. London : Printed by H.H. for Tho. Parkhurst at the Sign of the Bible and Three Crowns, at the lower end of Cheapside, 1681. Description: [12], 196, [20] p. ; 15 cm. References: Wing F 129. Subjects: Stockton, Owen, 1630-1680. Notes: Title enclosed within double line rule border. "Mors Triumphata; or The Saints Victory over Death; Opened in a Funeral Sermon ... " has special title page. 834 FAIRFAX, THOMAS FAIRFAX, Baron, 1612-1671. -

The Admission of Ministers in the Church of Scotland

THE ADMISSION OF MINISTERS IN THE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND 1560-1652. A Study la Fresfcgrteriaa Ordination. DUNCAN SHAW. A Thesis presented to THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW, For the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY, after study la THE DEPARTMENT OF ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY, April, 1976. ProQuest Number: 13804081 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13804081 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 X. A C KNQWLEDSMENT. ACKNOWLEDGMENT IS MADE OF TIE HELP AND ADVICE GIVEN TO THE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS BY THE REV. IAN MUIRHEAD, M.A., B.D., SENIOR LECTURER IN ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW. II. TABLES OP CONTENTS PREFACE Paso 1 INTRODUCTION 3 -11 The need for Reformation 3 Clerical ignorance and corruption 3-4 Attempto at correction 4-5 The impact of Reformation doctrine and ideas 5-6 Formation of the "Congregation of Christ" and early moves towards reform 6 Desire to have the Word of God "truelie preached" and the Sacraments "rightlie ministred" 7 The Reformation in Scotland -

Sotheby's Property from the Collection of Robert S Pirie Volumes I & II: Books and Manuscripts New York | 02 Dec 2015, 10:00 AM | N09391

Sotheby's Property From The Collection of Robert S Pirie Volumes I & II: Books and Manuscripts New York | 02 Dec 2015, 10:00 AM | N09391 LOT 9 (ALMANAC, ENGLISH) WRITING TABLES WITH A KALENDER FOR XXIIII YEERES, WITH SUNDRY NECESSARYE RULES. LONDON: PRINTED BY JAMES ROBERTS, FOR EDWARD WHITE, AND ARE TO BE SOLD AT THE LITTLE NORTH DORE OF PAULES, AT THE SIGNE OF THE GUNNE, 1598 16mo (3 5/8 x 2 1/2 in.; 93 x 66 mm). Title within woodcut border depicting Moses and Aaron, 3 leaves with woodcuts of coinage from various countries (total 6 pages), interleaved with 19 leaves containing a manuscript copy of a catechism dated 20 June 1610 and a 2–page geneaology of the Cholmeley family (1580–1601), and one leaf with the birth and death dates of one Edward Hanser (11 January 1811–10 August 1840, Arlington, Sussex), total of 38 pages; rather worn, title and last leaf frayed with loss of text. Contemporary doeskin wallet binding, blind-stamped; worn, one part of a clasp surviving only. Dark blue morocco-backed folding-case. ESTIMATE 4,000-6,000 USD Lot Sold: 16,250 USD PROVENANCE Cholmeley family (manuscript geneaology, 1580–1601) — Edward Hanser (birth and death dates in manuscript, 1810–1840) — Bromley K..., 1818–1846 (faded inscription inside rear front flap) — E.F. Bosanquet (bookplate on pastedown of case). acquisition: Pickering & Chatto LITERATURE STC 26050 (listing this copy and another at the University of Illinois); ESTC S113281 (cross-referenced to STC 26050 but naming Franke Adams as the maker in the title) CATALOGUE NOTE The eighth edition, one of two that mentions no maker of the tables in the title. -

The Coroner in Early Modern England, 1580-1630

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-12-18 Crown and Community: The Coroner in Early Modern England, 1580-1630 Murray, Danielle Jean Murray, D. J. (2013). Crown and Community: The Coroner in Early Modern England, 1580-1630 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/25493 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1210 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Crown and Community: The Coroner in Early Modern England, 1580-1630 by Danielle Jean Murray A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA December, 2013 © Danielle Jean Murray 2013 Abstract The role coroners played in English state formation between 1580 and 1630 is examined by looking at their relationship in the peripheries with other officials and by looking at their interactions with the state through the central court systems. Coroners were liminal figures who answered directly to the crown while maintaining loyalties to the local communities where they were elected and lived. Their role as a key interlocutor for both the crown and the community meant that they often had to deal with conflicting interests. -

Bibliography „Prieure De Sion“ and Rennes-Le-Chateau Ca

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography „Prieure de Sion“ and Rennes-le-Chateau Ca. 1300 title entries © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E26 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia: Bibliography „Prieure de Sion“ and Rennes-le-Chateau ca. 1300 title entries Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others). -

Historical Memoirs of the Reign of Mary, Queen of Scots, and a Portion Of

NAllONAl. LIBRARY OFSGO'II.AN]) iiililiiiiililiiitiliiM^^^^^ LORD HERRIES' MEMOIRS. -A^itt^caJi c y HISTORICAL MEMOIRS OF THE REIGN OF MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS, AND A PORTION OF THE REIGN OF KING JAMES THE SIXTH. LOED HEERIES. PRINTED AT EDINBURGH. M.DCCC.XXXVI. EDINBinr.H rniNTING COMPANY. PRESENTED myt atiftot^fora €luh ROBERT PITCAIRN. ABROTSFORD CLUB, iMDCCCXXXVI. JOHN HOPE, EsQoiKE. Right Hon. The Earl of Aberdeen. Adam Anderson, Esquire. Charles Baxter, Esquire. 5 Robert Blackwood, Esquire. BiNDON Blood, Esquire. Beriah Botfield, Esquire. Hon. Henry Cockburn, Lord Cockburn. John Payne Collier, Esquire. 10 Rev. Alexander Dyce, B.A. John Black Gracie, Esquire. James Ivory, Esquire. Hon. Francis Jeffrey, Lord Jeffrey. George Ritchie Kinloch, Esquire. 15 William Macdowall, Esquire. James Maidment, Esquire. Rev. James Morton. Alexander Nicholson, Esquire. Robert Pitcairn, Esquire. 20 Edward Pyper, Esquire. Andrew Rutheefurd, Esquire. Andrew Shortrede, Esquire. John Smith, Youngest, Esquire. Sir Patrick Walker, Knight. 25 John Whitefoord Mackenzie, Esquire. ^fctftarg. William B. D. D. Turnbull, Esquire. PREFATORY NOTICE. The following historical Memoir lias been selected by the Editor as the subject of his contribution to The Abbotsford Club—as well from the consideration of the interesting, but still obscure, period of Scottish history to which it refers, and which it materially tends to illustrate in many minute parti- culars—as from the fact that the transcript, or rather abridg- ment, of the original j\IS. by Lord Herries, now belonging to the Faculty of Advocates, is nearly all that is known to have been preserved of the valuable historical Collections made by the members of the Scots College of Douay, which, unfortu- nately, appear to have been totally destroyed during the French Revolution.