Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

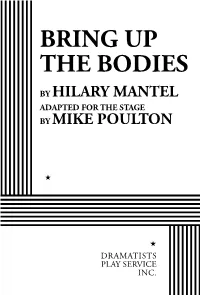

Bring up the Bodies

BRING UP THE BODIES BY HILARY MANTEL ADAPTED FOR THE STAGE BY MIKE POULTON DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. BRING UP THE BODIES Copyright © 2016, Mike Poulton and Tertius Enterprises Ltd Copyright © 2014, Mike Poulton and Tertius Enterprises Ltd Bring Up the Bodies Copyright © 2012, Tertius Enterprises Ltd All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of BRING UP THE BODIES is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for BRING UP THE BODIES are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

Arden of Faversham, Shakespearean Authorship, and 'The Print of Many'

Chapter 9 Arden of Faversham, Shakespearean Authorship, and 'The Print of Many' JACK ELLIOTT AND BRETT GREATLEY-HIRSCH he butchered body of Thomas Arden is found in the field behind the Abbey. After reporting Tthis discovery to Arden's wife, Franklin surveys the circumstantial evidence of footprints in the snow and blood at the scene: I fear me he was murdered in this house And carried to the fields, for from that place Backwards and forwards may you see The print of many feet within the snow. And look about this chamber where we are, And you shall find part of his guiltless blood; For in his slip-shoe did I find some rushes, Which argueth he was murdered in this room. (14.388-95) Although The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland by Raphael Holinshed and his editors records the identities and fates of Arden's murderers in meticulous detail (Holinshed 1587, 4M4r-4M6v; 1587, 5K1v-5K3v), those responsible for composing the dramatization of this tragic episode remain unknown. We know that the bookseller Edward White entered The Lamentable and True Tragedy ofArden ofFaversham in Kent into the Stationers' Register on 3 April 1592 (Arber 1875-94, 2: 607 ), and we believe, on the basis of typographical evidence, that Edward Allde printed the playbook later that year ( STC 733). We know that Abel Jeffes also printed an illicit edition of the playbook, as outlined in disciplinary proceedings brought against him and White in a Stationers' Court record dated 18 December 1592 (Greg and Boswell 1930, 44). No copies of this pirate edition survive, but it is assumed to have merely been a reprint of White's; Jeffes was imprisoned on 7 August 1592, so his edition must have appeared prior to this date. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph H. Records Collection Records, Ralph Hayden. Papers, 1871–1968. 2 feet. Professor. Magazine and journal articles (1946–1968) regarding historiography, along with a typewritten manuscript (1871–1899) by L. S. Records, entitled “The Recollections of a Cowboy of the Seventies and Eighties,” regarding the lives of cowboys and ranchers in frontier-era Kansas and in the Cherokee Strip of Oklahoma Territory, including a detailed account of Records’s participation in the land run of 1893. ___________________ Box 1 Folder 1: Beyond The American Revolutionary War, articles and excerpts from the following: Wilbur C. Abbott, Charles Francis Adams, Randolph Greenfields Adams, Charles M. Andrews, T. Jefferson Coolidge, Jr., Thomas Anburey, Clarence Walroth Alvord, C.E. Ayres, Robert E. Brown, Fred C. Bruhns, Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard, Benjamin Franklin, Carl Lotus Belcher, Henry Belcher, Adolph B. Benson, S.L. Blake, Charles Knowles Bolton, Catherine Drinker Bowen, Julian P. Boyd, Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Sanborn C. Brown, William Hand Browne, Jane Bryce, Edmund C. Burnett, Alice M. Baldwin, Viola F. Barnes, Jacques Barzun, Carl Lotus Becker, Ruth Benedict, Charles Borgeaud, Crane Brinton, Roger Butterfield, Edwin L. Bynner, Carl Bridenbaugh Folder 2: Douglas Campbell, A.F. Pollard, G.G. Coulton, Clarence Edwin Carter, Harry J. Armen and Rexford G. Tugwell, Edward S. Corwin, R. Coupland, Earl of Cromer, Harr Alonzo Cushing, Marquis De Shastelluz, Zechariah Chafee, Jr. Mellen Chamberlain, Dora Mae Clark, Felix S. Cohen, Verner W. Crane, Thomas Carlyle, Thomas Cromwell, Arthur yon Cross, Nellis M. Crouso, Russell Davenport Wallace Evan Daview, Katherine B. -

Anna Bolena Opera by Gaetano Donizetti

ANNA BOLENA OPERA BY GAETANO DONIZETTI Presentation by George Kurti Plohn Anna Bolena, an opera in two acts by Gaetano Donizetti, is recounting the tragedy of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of England's King Henry VIII. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, Donizetti was a leading composer of the bel canto opera style, meaning beauty and evenness of tone, legato phrasing, and skill in executing highly florid passages, prevalent during the first half of the nineteenth century. He was born in 1797 and died in 1848, at only 51 years of age, of syphilis for which he was institutionalized at the end of his life. Over the course of is short career, Donizetti was able to compose 70 operas. Anna Bolena is the second of four operas by Donizetti dealing with the Tudor period in English history, followed by Maria Stuarda (named for Mary, Queen of Scots), and Roberto Devereux (named for a putative lover of Queen Elizabeth I of England). The leading female characters of these three operas are often referred to as "the Three Donizetti Queens." Anna Bolena premiered in 1830 in Milan, to overwhelming success so much so that from then on, Donizetti's teacher addressed his former pupil as Maestro. The opera got a new impetus later at La Scala in 1957, thanks to a spectacular performance by 1 Maria Callas in the title role. Since then, it has been heard frequently, attracting such superstar sopranos as Joan Sutherland, Beverly Sills and Montserrat Caballe. Anna Bolena is based on the historical episode of the fall from favor and death of England’s Queen Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII. -

Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn's Femininity Brought Her Power and Death

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Senior Honors Projects Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2018 Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn’s Femininity Brought her Power and Death Rebecca Ries-Roncalli John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Ries-Roncalli, Rebecca, "Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn’s Femininity Brought her Power and Death" (2018). Senior Honors Projects. 111. https://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers/111 This Honors Paper/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Patriarchal Dynamics in Politics: How Anne Boleyn’s Femininity Brought her Power and Death Rebecca Ries-Roncalli Senior Honors Project May 2, 2018 Ries-Roncalli 1 I. Adding Dimension to an Elusive Character The figure of Anne Boleyn is one that looms large in history, controversial in her time and today. The second wife of King Henry VIII, she is most well-known for precipitating his break with the Catholic Church in order to marry her. Despite the tremendous efforts King Henry went to in order to marry Anne, a mere three years into their marriage, he sentenced her to death and immediately married another woman. Popular representations of her continue to exist, though most Anne Boleyns in modern depictions are figments of a cultural imagination.1 What is most telling about the way Anne is seen is not that there are so many opinions, but that throughout over 400 years of study, she remains an elusive character to pin down. -

Dissertation Title Page

“Singing by Course” and the Politics of Worship in the Church of England, c1560–1640 By James Campbell Nelson Apgar A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor James Davies Professor Diego Pirillo Spring 2018 Abstract “Singing by Course” and the Politics of Worship in the Church of England, c1560–1640 by James Campbell Nelson Apgar Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair “Singing by course” was both a product of and a rhetorical tool within the religious discourses of post-Reformation England. Attached to a variety of ostensibly distinct practices, from choirs singing alternatim to congregations praying responsively, it was used to advance a variety of partisan agendas regarding performance and sound within the services of the English Church. This dissertation examines discourses of public worship that were conducted around and through “singing by course,” treating it as a linguistic and conceptual node within broader networks of contemporary religious debate. I thus attend less to the history of the vocal practices to which “by course” and similar descriptions were applied than to the polemical dynamics of these applications. Discussions of these terms and practices slipped both horizontally, to other matters of ritual practice, and vertically, to larger topics or frameworks such as the nature of the Christian Church, the production of piety, and the roles of sound and performance in corporate prayer. Through consideration of these issues, “singing by course” emerges as a rhetorical, political, and theological construction, one that circulated according to changing historical conditions and to the interests of various ecclesiastical constituencies. -

Illustrated and Descriptive Catalogue and Price List of Stereopticons

—. ; I, £3,v; and Descriptive , Illustrated ;w j CATALOGUE AND PRICE LIST- t&fs — r~* yv4 • .'../-.it *.•:.< : .. 4^. ; • ’• • • wjv* r,.^ N •’«* - . of . - VJ r .. « 7 **: „ S ; \ 1 ’ ; «•»'•: V. .c; ^ . \sK? *• .* Stereopticons . * ' «». .. • ” J- r . .. itzsg' Lantern Slides 1 -f ~ Accessories for Projection Stereopticon and Film Exchange W. B. MOORE, Manager. j. :rnu J ; 104 to no Franlclin Street ‘ Washington . (Cor. CHICAGO INDEX TO LANTERNS, ETC. FOR INDEX TO SLIDES SEE INDEX AT CLOSE OF CATALOGUE. Page Acetylene Dissolver 28 Champion Lantern 3g to 42 “ Gas 60 Check Valve S3 •* 1 • .• Gas Burner.... ; 19 Chemicals, Oxygen 74, 81 ** < .' I j Gas Generator.. ; 61 to 66 Chirograph 136 “ Gas Generator, Perfection to 66 64 Chlorate of Potash, tee Oxygen Chemicals 74 Adapter from to sire lenses, see Chromatrope.... 164 Miscellaneous....... 174 Cloak, How Made 151 Advertising Slides, Blank, see Miscellaneous.. 174 ** Slides 38010,387 " Slides 144 Color Slides or Tinters .^140 “ Slides, Ink for Writing, see Colored Films 297 Miscellaneous, 174 Coloring Films 134 “ Posters * *...153 " Slides Alcohol Vapor Mantle Light 20A v 147 Combined Check or Safety Valve 83 Alternating.Carbons, Special... 139 Comic and Mysterious Films 155 Allen Universal Focusing Lens 124, 125 Comparison of Portable Gas Outfits 93, 94 America, Wonders cf Description, 148 “Condensing Lens 128 Amet's Oro-Carbi Light 86 to 92, 94 " Lens Mounting 128 •Ancient Costumes ....! 131 Connections, Electric Lamp and Rheostat... 96, 97 Approximate Length of Focus 123 " Electric Stage 139 Arc Lamp 13 to 16 Costumes 130 to 152, 380 to 3S7 ** Lamp and Rheostat, How to Connect 96 Cover Glasses, see Miscellaneous ,....174 Arnold's Improved Calcium Light Outfit. -

Title Jest-Book Formation Through the Early Modern Printing Industry

Title Jest-book formation through the early modern printing industry: the two different editions of Scoggin's Jests Sub Title 二つのScoggin's Jests : 異なる版が語ること Author 小町谷, 尚子(Komachiya, Naoko) Publisher 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要刊行委員会 Publication year 2014 Jtitle 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要. 英語英米文学 (The Hiyoshi review of English studies). No.65 (2014. 10) ,p.45- 85 Abstract Notes Genre Departmental Bulletin Paper URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=AN10030060-2014103 1-0045 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって 保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守してご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Jest-book Formation through the Early Modern Printing Industry: The Two Different Editions of Scoggin’s Jests Naoko Komachiya The confusion and conflation of differently originated jester figures date back to Shakespeare’s time. Scoggin’s Jests is often seen as the primary source of jesting material along with Tarlton’s Jests. The apparent identity of these jests with named figures somewhat obscured the true identity of jesters.1) Modern editors identify the socially ambiguous jester Scoggin in Shallow’s episodic recollection of Falstaff, who breaks ‘Scoggin’s head at the court gate’ in Henry IV, Part 2 (III. 2. 28–29), as the jester to Edward IV. René Weis, in explaining that Scoggin’s name was ‘synonymous with “buffoon” in Shakespeare’s day through a mid sixteenth-century jestbook, Scoggin, his iestes’, comments that the reference demonstrates that ‘even the young Falstaff was always brawling with various buffoons’.2) Weis and other editors simply deduce that Shakespeare’s misunderstanding resulted from the circulated name of Scoggin, and they do not show any evidence how the conflation occurred. -

Ambassadors to and from England

p.1: Prominent Foreigners. p.25: French hostages in England, 1559-1564. p.26: Other Foreigners in England. p.30: Refugees in England. p.33-85: Ambassadors to and from England. Prominent Foreigners. Principal suitors to the Queen: Archduke Charles of Austria: see ‘Emperors, Holy Roman’. France: King Charles IX; Henri, Duke of Anjou; François, Duke of Alençon. Sweden: King Eric XIV. Notable visitors to England: from Bohemia: Baron Waldstein (1600). from Denmark: Duke of Holstein (1560). from France: Duke of Alençon (1579, 1581-1582); Prince of Condé (1580); Duke of Biron (1601); Duke of Nevers (1602). from Germany: Duke Casimir (1579); Count Mompelgart (1592); Duke of Bavaria (1600); Duke of Stettin (1602). from Italy: Giordano Bruno (1583-1585); Orsino, Duke of Bracciano (1601). from Poland: Count Alasco (1583). from Portugal: Don Antonio, former King (1581, Refugee: 1585-1593). from Sweden: John Duke of Finland (1559-1560); Princess Cecilia (1565-1566). Bohemia; Denmark; Emperors, Holy Roman; France; Germans; Italians; Low Countries; Navarre; Papal State; Poland; Portugal; Russia; Savoy; Spain; Sweden; Transylvania; Turkey. Bohemia. Slavata, Baron Michael: 1576 April 26: in England, Philip Sidney’s friend; May 1: to leave. Slavata, Baron William (1572-1652): 1598 Aug 21: arrived in London with Paul Hentzner; Aug 27: at court; Sept 12: left for France. Waldstein, Baron (1581-1623): 1600 June 20: arrived, in London, sightseeing; June 29: met Queen at Greenwich Palace; June 30: his travels; July 16: in London; July 25: left for France. Also quoted: 1599 Aug 16; Beddington. Denmark. King Christian III (1503-1 Jan 1559): 1559 April 6: Queen Dorothy, widow, exchanged condolences with Elizabeth. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS EDITED BY MICHAEL P. WEBER The Good Provider: H. J. Heinz and His 57 Varieties. By Robert C. Alberts. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973. Pp. 297. $10.00.) Who has not at some time sampled one of Heinz's 57 Varieties? Everyone who likes to eat will be interested in this biography of H. J. Heinz by Robert Alberts, who gave such an entertaining talk on William Bingham at the an- nual meeting of the Pennsylvania Historical Association a few years ago. This particular volume is the outgrowth of an article in American Heritage magazine and still shows signs of being intended for a popular rather than a scholarly audience. It is a sympathetic account of a simple, honest, hardworking, deeply religious son of German immigrants who embodied the Horatio Alger tradition without being an especially complex or interesting person. Nevertheless, it reminds us how many of today's famous firms were originally such personal enterprises. It is a little surprising, however, that Mr. Alberts places Heinz on the same level as other Pittsburgh magnates like Carnegie, Frick, Mellon, and Westinghouse, with whom he seems to have had relatively little communication. Yet certainly the story of the Heinz company is a significant aspect of nineteenth-century social history, reflecting as it does changes in the American diet made possible by new developments in transportation, re- frigeration, and the preservation of food in cans. The book shows that the company's success was based on a combination of large-scale production and skillful techniques in public relations and advertising. -

Collecting and Representing Saxon Identity in the Dresden Kunstkammer and Princely Monuments in Freiberg Cathedral

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE International Projects with a Local Emphasis: Collecting and Representing Saxon Identity in the Dresden Kunstkammer and Princely Monuments in Freiberg Cathedral A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Daniel A. Powazek June 2020 Thesis Committee: Dr. Kristoffer Neville, Chairperson Dr. Randolph Head Dr. Jeanette Kohl Copyright by Daniel A. Powazek 2020 The Thesis of Daniel A. Powazek is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS International Projects with a Local Emphasis: The Collecting and Representation of Saxon Identity in the Dresden Kunstkammer and Princely Monuments in Freiberg Cathedral by Daniel A. Powazek Master of Arts, Graduate Program in Art History University of California, Riverside, June 2020 Dr. Kristoffer Neville, Chairperson When the Albertine Dukes of Saxony gained the Electoral privilege in the second half of the sixteenth century, they ascended to a higher echelon of European princes. Elector August (r. 1553-1586) marked this new status by commissioning a monumental tomb in Freiberg Cathedral in Saxony for his deceased brother, Moritz, who had first won the Electoral privilege for the Albertine line of rulers. The tomb’s magnificence and scale, completed in 1563, immediately set it into relation to the grandest funerary memorials of Europe, the tombs of popes and monarchs, and thus establishing the new Saxon Electors as worthy peers in rank and status to the most powerful rulers of the period. By the end of his reign, Elector August sought to enshrine the succeeding rulers of his line in an even grander project, a dynastic chapel built into Freiberg Cathedral directly in front of the tomb of Moritz.