Johann Reuchlin's Open Letter of 1505

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juan Latino and the Dawn of Modernity

Juan Latino and the Dawn of Modernity May, 2017 Michael A. Gómez Professor of History and Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies New York University Juan Latino’s first book is in effect a summons not only to meditate upon the person and his work, but to reconsider the birth of a new world order from a vantage point both unique and unexpected, to view the beginning of a global transformation so thoroughgoing in its effect that the world continues to wrestle with its implications, its overall direction yet determined by centuries-old centripetal forces. The challenge, therefore in seeing the world through the eyes of Juan Latino is to resist or somehow avoid the optic of the present, since we know what has transpired in the nearly five hundred year since the birth of Juan Latino, and that knowledge invariably affects, if not skews our understanding of the person and his times. Though we may not fully succeed, there is much to gain from paying disciplined attention to matters of periodization in the approximation of Juan Latino’s world, in the effort to achieve new vistas into the human condition. To understand Juan Latino, therefore, is to grapple with political, cultural, and social forces, global in nature yet still in their infancy, which created him. To grasp the significance of Juan Latino is to come to terms with contradiction and contingency, verity and surprise, ambiguity and clarity, conformity and exceptionality. In the end, the life and times of Juan Latino constitute a rare window into the dawn of modernity. Celebrated as “the first person of sub-Saharan African descent to publish a book of poems in a western language” (a claim sufficiently qualified as to survive sustained scrutiny), Juan Latino, as he came to be known, was once “Juan de Sessa,” the slave of a patrician family, who came to style himself as “Joannes Latīnūs,” often signing his name as “Magīster Latīnūs.”i The changing, shifting nomenclature is as revealing as it is obfuscating. -

Academic Genealogy of Mason A. Porter C

Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī Kamāl al-Dīn Ibn Yūnus Nasir al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī Shams al‐Dīn al‐Bukhārī Maragheh Observatory Gregory Chioniadis 1296 Ilkhans Court at Tabriz Manuel Bryennios Theodore Metochites 1315 Gregory Palamas Nilos Kabasilas Nicole Oresme 1363 Heinrich von Langenstein Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus 1363 Université de Paris 1375 Université de Paris Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos Johannes von Gmunden 1380, 1393 1406 Universität Wien Basilios Bessarion Georg von Peuerbach 1436 Mystras 1440 Universität Wien Johannes Müller Regiomontanus Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1457 Universität Leipzig 1408 1444 Università degli Studi di Padova 1457 Universität Wien Vittorino da Feltre Marsilio Ficino Cristoforo Landino 1416 Università degli Studi di Padova 1462 Università degli Studi di Firenze Theodoros Gazes Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Paolo (Nicoletti) da Venezia Angelo Poliziano Florens Florentius Radwyn Radewyns Geert Gerardus Magnus Groote 1433 Università di Mantova Università di Mantova 1477 Università degli Studi di Firenze 1433 Constantinople Sigismondo Polcastro Demetrios Chalcocondyles Leo Outers Gaetano da Thiene Georgius Hermonymus Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Rudolf Agricola Thomas von Kempen à Kempis Jacob ben Jehiel Loans 1412 Università degli Studi di Padova 1452 Mystras 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università degli Studi di Firenze 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1424 Università degli Studi di Padova 1452 Accademia Romana Jacques (Jacobus Faber) Lefèvre -

Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Department Of

Basilios Bessarion Mystras 1436 Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 Università di Padova 1444 Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Vittorino da Feltre Marsilio Ficino Cristoforo Landino Università di Padova 1416 Università di Firenze 1462 Theodoros Gazes Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Angelo Poliziano Florens Florentius Radwyn Radewyns Geert Gerardus Magnus Groote Università di Mantova 1433 Università di Mantova Università di Firenze 1477 Constantinople 1433 DepartmentThe Mathematics Genealogy Project of is a serviceMathematics of North Dakota State University and and the American Statistics Mathematical Society. Demetrios Chalcocondyles http://www.mathgenealogy.org/ Heinrich von Langenstein Gaetano da Thiene Sigismondo Polcastro Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Rudolf Agricola Thomas von Kempen à Kempis Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Accademia Romana 1452 Université de Paris 1363, 1375 Université Catholique de Louvain 1485 Università di Firenze 1493 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1478 Mystras 1452 Jan Standonck Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Johannes von Gmunden Nicoletto Vernia Pietro Roccabonella Pelope Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Jean Tagault François Dubois Janus Lascaris Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Matthaeus Adrianus Alexander Hegius Johannes Stöffler Collège Sainte-Barbe 1474 Universität Basel 1477 Universität Wien 1406 Università di Padova Università di Padova Université Catholique de Louvain 1504, 1515 Université de Paris 1516 Università di Padova 1472 Università -

Abeka Scope & Sequence Booklet 2020-2021

GRADE 10 ENGLISH: Grammar & Composition t c n N o cti ou rje n e te C e e j In la s s u b r s n e n p e O e a e se Di P a re T r T c O h h t c e P r u b O b t b a c j e s r t r e y s l u i P e t e e i re R n a e d n V l i y V c U a a s t R e s t r E e C o N p omin tive a builds upon the grammar foundation established in previous years e h c Grammar and Composition IV i p Grammar o a V P h r a s e r s g e d n N v a u i o r r u s e n a s G uati s t o P a c n o n P s u t C f d P D n n a y n p e i a a and introduces new concepts to further enhance the students’ knowledge of basic grammar. In r i e t m m s a e c & e e s l l l v RAMMAR i t i z p p E t E a G A t m m c i o o o d C C n A d r e e s s e s s s a a & r r I h n omposition P f n e i v t i h P Composition Ce s WORK-TEXT a p i r t c i o s r n e e h s D addition, this text emphasizes explanative writing by having students write essays, an extended Fourth Edition v P i D t b b y i r r r IV c r e e e a V A V r r e e c n p p t o a a n i O e t g P P u in v c m b o a g i i r g h h t j n a N i i i e D D c c s s r c e m r t r t n e t a s L e a e a e n r r s s v e e i s o g I T t a definition, a process paper, a literary theme, critical book reviews, and a research paper. -

Eu Whoiswho Official Directory of the European Union

EUROPEAN UNION EU WHOISWHO OFFICIAL DIRECTORY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION EUROPEAN COMMISSION 16/09/2021 Managed by the Publications Office © European Union, 2021 FOP engine ver:20180220 - Content: - merge of files"Commission_root.xml", "The_College.XML1.5.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_CABINETS.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_SG.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/ CRF_COM_SJ.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_COMMU.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_IDEA.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_BUDG.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/ CRF_COM_HR.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_DIGIT.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_IAS.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_OLAF.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/ CRF_COM_ECFIN.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_GROW.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_DEFIS.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_COMP.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/ CRF_COM_EMPL.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_AGRI.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_MOVE.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_ENER.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/ CRF_COM_ENV.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_CLIMA.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_RTD.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/CRF_COM_CNECT.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", "temp/ CRF_COM_JRC.RNS.FX.TRAD.DPO.dated.XML1.5.ANN.xml", -

Italian Painters, Critical Studies of Their Works: the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden

Italian Painters, Critical Studies of their Works: the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden. An overview of Giovanni Morelli’s attributions1 Valentina Locatelli ‘This magnificent picture-gallery [of Dresden], unique in its way, owes its existence chiefly to the boundless love of art of August III of Saxony and his eccentric minister, Count Brühl.’2 With these words the Italian art connoisseur Giovanni Morelli (Verona 1816–1891 Milan) opened in 1880 the first edition of his critical treatise on the Old Masters Picture Gallery in Dresden (hereafter referred to as ‘Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister’). The story of the Saxon collection can be traced back to the 16th century, when Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) was the court painter to the Albertine Duke George the Bearded (1500–1539). However, Morelli’s remark is indubitably correct: it was in fact not until the reign of Augustus III (1696– 1763) and his Prime Minister Heinrich von Brühl (1700–1763) that the gallery’s most important art purchases took place.3 The year 1745 marks a decisive moment in the 1 This article is the slightly revised English translation of a text first published in German: Valentina Locatelli, ‘Kunstkritische Studien über italienische Malerei: Die Galerie zu Dresden. Ein Überblick zu Giovanni Morellis Zuschreibungen’, Jahrbuch der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 34, (2008) 2010, 85–106. It is based upon the second, otherwise unpublished section of the author’s doctoral dissertation (in Italian): Valentina Locatelli, Le Opere dei Maestri Italiani nella Gemäldegalerie di Dresda: un itinerario ‘frühromantisch’ nel pensiero di Giovanni Morelli, Università degli Studi di Bergamo, 2009 (available online: https://aisberg.unibg.it/bitstream/10446/69/1/tesidLocatelliV.pdf (accessed September 9, 2015); from here on referred to as Locatelli 2009/II). -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

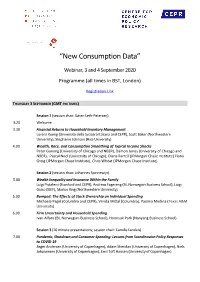

“New Consumption Data”

“New Consumption Data” Webinar, 3 and 4 September 2020 Programme (all times in BST, London) Registration Link THURSDAY 3 SEPTEMBER (GMT PM TIMES) Session 1 (session chair: Søren Leth-Petersen) 3:20 Welcome 3.30 Financial Returns to Household Inventory Management Lorenz Kueng (Universita della Svizzera Italiana and CEPR), Scott Baker (Northwestern University), Stephanie Johnson (Rice University) 4.00 Wealth, Race, and Consumption Smoothing of Typical Income Shocks Peter Ganong (University of Chicago and NBER), Damon Jones (University of Chicago and NBER), Pascal Noel (University of Chicago), Diana Farrell (JPMorgan Chase Institute) Fiona Greig (JPMorgan Chase Institute), Chris Wheat (JPMorgan Chase Institute) Session 2 (session chair: Johannes Spinnewijn) 5.00 Wealth Inequality and Insurance Within the Family Luigi Pistaferri (Stanford and CEPR), Andreas Fagereng (BI, Norwegian Business School), Luigi Guiso (EIEF), Marius Ring (Northwestern University) 5.30 Bumped: The Effects of Stock Ownership on Individual Spending Michaela Pagel (Columbia and CEPR), Vrinda Mittal (Columbia), Paolina Medina (Texas A&M University) 6.00 Firm Uncertainty and Household Spending Ivan Alfaro (BI, Norwegian Business School), Hoonsuk Park (Nanyang Business School) Session 3 (10 minute presentations; session chair: Camille Landais) 7.00 Pandemic, Shutdown and Consumer Spending: Lessons from Scandinavian Policy Responses to COVID-19 Asger Andersen (University of Copenhagen), Adam Sheridan (University of Copenhagen), Niels Johannesen (University of Copenhagen), Emil Toft Hansen (University of Copenhagen) 7.10 Income, Liquidity, and the Consumption Response to the 2020 Economic Stimulus Payments Constantine Yannelis (Chicago Booth), Scott R. Baker (Northwestern University), Michaela Pagel (Columbia and CEPR) , Steffen Meyer (University of Southern Denmark, SDU) , Robert A Farrokhnia (Columbia) 7.20 What and how did people buy during the Great Lockdown? Evidence from electronic payments Joao Pereira dos Santos (Nova School of Business and Economics) Bruno P. -

High Clergy and Printers: Antireformation Polemic in The

bs_bs_banner High clergy and printers: anti-Reformation polemic in the kingdom of Poland, 1520–36 Natalia Nowakowska University of Oxford Abstract Scholarship on anti-Reformation printed polemic has long neglected east-central Europe.This article considers the corpus of early anti-Reformation works produced in the Polish monarchy (1517–36), a kingdom with its own vocal pro-Luther communities, and with reformed states on its borders. It places these works in their European context and, using Jagiellonian Poland as a case study, traces the evolution of local polemic, stresses the multiple functions of these texts, and argues that they represent a transitional moment in the Polish church’s longstanding relationship with the local printed book market. Since the nineteen-seventies, a sizeable literature has accumulated on anti-Reformation printing – on the small army of men, largely clerics, who from c.1518 picked up their pens to write against Martin Luther and his followers, and whose literary endeavours passed through the printing presses of sixteenth-century Europe. In its early stages, much of this scholarship set itself the task of simply mapping out or quantifying the old church’s anti-heretical printing activity. Pierre Deyon (1981) and David Birch (1983), for example, surveyed the rich variety of anti-Reformation polemical materials published during the French Wars of Religion and in Henry VIII’s England respectively.1 John Dolan offered a panoramic sketch of international anti-Lutheran writing in an important essay published in 1980, while Wilbirgis Klaiber’s landmark 1978 database identified 3,456 works by ‘Catholic controversialists’ printed across Europe before 1600.2 This body of work triggered a long-running debate about how we should best characterize the level of anti-Reformation printing in the sixteenth century. -

Chapter Twenty-Eight Beginning of the Burning Times in Western

Chapter Twenty-eight Beginning of the Burning Times in Western Christendom Western Europe did not progress steadily from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. While the privileged classes enjoyed the advent of humanism, among the masses religiosity intensified. Of this the most important consequence was the Protestant Reformation. Millions of Christians abandoned their belief in the power of saints, relics, Mary, and the Church, but their devotion to other aspects of Christianity was fierce and often fanatic. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Europeans by the hundred thousands died for religious reasons, Catholics burning heretics, Protestants burning witches, and both killing each other on the battlefield. The eighteenth-century Enlightenment was in part a reaction to the religious frenzy of the two preceding centuries. Trade, exploration, and the first European empires In the fifteenth century, as the wealthy classes of Catholic Europe developed a taste for luxury goods from India and the Far East, east-west trade became very lucrative. Silk from China was highly prized, as were the spices - cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, pepper - from Sri Lanka, India, and the “Spice Islands” of Indonesia. Because most of this trade still passed through the Red Sea or overland on the caravan routes of the Hijaz, it enriched the Mamluk rulers who controlled all of Egypt and much of the Levant, and Cairo became the cultural center of the Dar al-Islam. Although menaced by the Ottomans, the Mamluks were able to hold their own until the early sixteenth century. European merchants were eager to capitalize on trade with eastern Asia, and Spanish and especially Portuguese explorers looked for a sea-route to India that would by-pass the Mamluks as well as the Ottomans. -

Humanism and Hebraism: Christian Scholars and Hebrew Sources in the Renaissance

Humanism and Hebraism: Christian Scholars and Hebrew Sources in the Renaissance Kathryn Christine Puzzanghera Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Religion April 2016 © 2016 Kathryn C. Puzzanghera, All Rights Reserved This thesis is dedicated to the glory of God Who gave us reason, creativity, and curiosity, that they might be used AND To the mixed Protestant-Catholic family I was born into, and the Jewish family we chose Table of Contents Chapter I: Christian Humanist Hebraism in Context .................................... 1 Christian Thought and Biblical Exegesis ......................................................................... 8 Jewish-Christian Dialogue and Anti-Semitism .............................................................. 17 Scholastics and Humanists in dialogue .......................................................................... 29 Christian Hebraists: Medieval Exegetes, Renaissance Humanists, and Protestant Reformers ....................................................................................................................... 43 Renaissance Hebraists: Nicholas of Lyra, Johannes Reuchlin, and Philip Melanchthon ........................................................................................................................................ 55 Chapter II: Nicholas of Lyra ...........................................................................58 Nicholas in Dialogue: Influences and Critiques ............................................................. 71 Nicholas’s -

The Significance of the Sermons of Wenzeslaus Linck

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 69-4864 DANIEL, Jr., Charles Edgar, 1933- THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SERMONS OF WENZESLAUS LINCK. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 History, modern Religion University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SERMONS OF WENZESLAUS LINCK DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Charles Edgar Daniel, Jr., B.A., A.M., M.A. The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by S J L A V S LINCK, ColditiiiuuyM ifhictfS > jLf.S.’7%iei*<fiae. fleeter*,& Jinistdtyurtm iiitjpr'utn ajmd 'W Utibir^in/ei vt'imtun vraidtcaiof* * dmupn ‘fyartuslh'tfnruialis,diinde^/tinpuf^iadtJ*it tan,, a *Jim #aft a ai ^d. jsb f'JVjrtfreraaifljt ^MriteracnJijJEicfaJiai/ w JLtcfl ital in jCinin dickii ACKN0WLEDQ1ENTS I wish to express my deepest gratitude to Professor Harold J. Grimm of the Department of History, The Ohio State University. His patience and encouragement were of incalculable aid to me in the production of this dissertation. I also would like to acknowledge the assist ance given me by Professor Gerhard Pfeiffer of the Univer sity of Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany. By his intimate know ledge of Nttrnberg's past he made its history live for me. Jfirgen Ohlau helped me in my use of source materials. I greatly treasure his friendship. iii VITA 12 February 1933 Born - Columbia, Missouri 1955............ B.A., University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 1955-1957 • • • • Graduate Assistant, Depart ment of History, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 1957 .