Electing a Diverse Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

FSU Immigrants in Canada: a Case of Positive Triple Selection?

IZA DP No. 4410 FSU Immigrants in Canada: A Case of Positive Triple Selection? Don DeVoretz Michele Battisti September 2009 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor FSU Immigrants in Canada: A Case of Positive Triple Selection? Don DeVoretz Simon Fraser University and IZA Michele Battisti Simon Fraser University Discussion Paper No. 4410 September 2009 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA Discussion Paper No. 4410 September 2009 ABSTRACT FSU Immigrants in Canada: A Case of Positive Triple Selection?* This paper investigates the economic performance of immigrants from the Former Soviet Union (FSU) countries in Canada. -

Wednesday, March 23, 1994

VOLUME 133 NUMBER 043 1st SESSION 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, March 23, 1994 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, March 23, 1994 The House met at 2 p.m. anglophone and francophone families in Quebec has narrowed from 8.2 per cent to 1.9 per cent. _______________ The income gap can be closed, Mr. Speaker, but one has to Prayers conclude that federal policies are not a contributing factor. _______________ * * * [English] STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS CREDIT RATING [English] Mr. Jim Gouk (Kootenay West—Revelstoke): Mr. Speaker, BIODIVERSITY yesterday after the announcement of the downgrading of Cana- da’s rating for foreign currency debt, the Minister of Finance Hon. Charles Caccia (Davenport): Mr. Speaker, biodivers- stated it only affected a small portion of our total debt so it was ity means a richness of life as it surrounds us in nature. We must no big deal. preserve biodiversity because it is nature’s protection against catastrophes. The loss of biodiversity has serious implications Now the Bank of Canada has increased its key lending rate for life on earth. which undoubtedly will result in increased borrowing costs for Canadian consumers and businesses. It is also having an impact We have been told that since the beginning of the century 75 on the cost of government borrowing. per cent of crop diversity has been lost. This leaves us vulner- able. For example uniformity in corn crops could have resulted The budget did not address the deficit or debt. Now all in disaster when a severe blight threatened corn crops in the Canadians are starting to pay for this short–sightedness. -

Mon 18 Apr 2005 / Lun 18 Avr 2005

No. 130A No 130A ISSN 1180-2987 Legislative Assembly Assemblée législative of Ontario de l’Ontario First Session, 38th Parliament Première session, 38e législature Official Report Journal of Debates des débats (Hansard) (Hansard) Monday 18 April 2005 Lundi 18 avril 2005 Speaker Président Honourable Alvin Curling L’honorable Alvin Curling Clerk Greffier Claude L. DesRosiers Claude L. DesRosiers Hansard on the Internet Le Journal des débats sur Internet Hansard and other documents of the Legislative Assembly L’adresse pour faire paraître sur votre ordinateur personnel can be on your personal computer within hours after each le Journal et d’autres documents de l’Assemblée législative sitting. The address is: en quelques heures seulement après la séance est : http://www.ontla.on.ca/ Index inquiries Renseignements sur l’index Reference to a cumulative index of previous issues may be Adressez vos questions portant sur des numéros précédents obtained by calling the Hansard Reporting Service indexing du Journal des débats au personnel de l’index, qui vous staff at 416-325-7410 or 325-3708. fourniront des références aux pages dans l’index cumulatif, en composant le 416-325-7410 ou le 325-3708. Copies of Hansard Exemplaires du Journal Information regarding purchase of copies of Hansard may Pour des exemplaires, veuillez prendre contact avec be obtained from Publications Ontario, Management Board Publications Ontario, Secrétariat du Conseil de gestion, Secretariat, 50 Grosvenor Street, Toronto, Ontario, M7A 50 rue Grosvenor, Toronto (Ontario) M7A 1N8. Par 1N8. Phone 416-326-5310, 326-5311 or toll-free téléphone : 416-326-5310, 326-5311, ou sans frais : 1-800-668-9938. -

City of London

300 Oufferin Avenue P.O. Box 5035 London, ON N6A4L9 London CANADA December 6,2005 Chair and Members Board of Control RE: Meeting of the National Board of Directors - Federation Canadian Municipalities Ottawa, Ontario - December I-3,2005 We are very pleased to provide the following summary and a copy of the FCM's election strategy for the Board of Control's information: INTRODUCTION Overview FCM's National Board of Directors met in Ottawa, December 1-3, 2005, for its regular meeting. With the January 23 federal election as a backdrop, the Board called on all federal parties to clarify where they stand on key municipal issues. Of specific concern during the course of the campaign, the Board identified the need to secure a long-term legislated commitment to eliminating the infrastructure deficit, as well as the need to secure the quick transfer of money for affordable housing and transit contained in Bill C-48, and to develop a strong partnership between the Government of Canada and the municipal sector. As part of this call, the Board urged the broadcasters' consortium that will organize the four scheduled leader's debates to guarantee municipal issues would be discussed (see attached news release). Televised debate In keeping with its proactive strategy, the Board kicked off the proceedings with a nationally broadcast town-hall meeting with representatives of the Liberal, Conservative and New Democratic parties to discuss and debate where the three parties stand on municipal issues. Board members heard and questioned John Godfrey, Minister of State for Infrastructure and Communities, and opposition critics Rahim Jaffer of the Conservative Party of Canada and David Christopherson of the New Democratic Party. -

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 140, No. 3 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 140, no 3 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 3, 2006 OTTAWA, LE VENDREDI 3 FÉVRIER 2006 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 39th general election Rapport de députés(es) élus(es) à la 39e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of Members to serve in the House of ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de députés(es) à Commons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Députés(es) South Surrey—White Rock— Russ Hiebert Surrey-Sud—White Rock— Russ Hiebert Cloverdale Cloverdale Kitchener—Conestoga Harold Glenn Albrecht Kitchener—Conestoga Harold Glenn Albrecht Wild Rose Myron Thompson Wild Rose Myron Thompson West Vancouver—Sunshine Blair Wilson West Vancouver—Sunshine Blair Wilson Coast—Sea to Sky Country Coast—Sea to Sky Country Nepean—Carleton Pierre Poilievre Nepean—Carleton Pierre Poilievre Whitby—Oshawa Jim Flaherty Whitby—Oshawa Jim Flaherty Saint-Hyacinthe—Bagot Yvan Loubier Saint-Hyacinthe—Bagot Yvan Loubier Sudbury Diane Marleau Sudbury Diane Marleau Toronto—Danforth -

PRISM::Advent3b2 8.25

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 39th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 39e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 1 No 1 Monday, April 3, 2006 Le lundi 3 avril 2006 11:00 a.m. 11 heures Today being the first day of the meeting of the First Session of Le Parlement se réunit aujourd'hui pour la première fois de la the 39th Parliament for the dispatch of business, Ms. Audrey première session de la 39e législature, pour l'expédition des O'Brien, Clerk of the House of Commons, Mr. Marc Bosc, Deputy affaires. Mme Audrey O'Brien, greffière de la Chambre des Clerk of the House of Commons, Mr. R. R. Walsh, Law Clerk and communes, M. Marc Bosc, sous-greffier de la Chambre des Parliamentary Counsel of the House of Commons, and Ms. Marie- communes, M. R. R. Walsh, légiste et conseiller parlementaire de Andrée Lajoie, Clerk Assistant of the House of Commons, la Chambre des communes, et Mme Marie-Andrée Lajoie, greffier Commissioners appointed per dedimus potestatem for the adjoint de la Chambre des communes, commissaires nommés en purpose of administering the oath to Members of the House of vertu d'une ordonnance, dedimus potestatem, pour faire prêter Commons, attending according to their duty, Ms. Audrey O'Brien serment aux députés de la Chambre des communes, sont présents laid upon the Table a list of the Members returned to serve in this dans l'exercice de leurs fonctions. Mme Audrey O'Brien dépose sur Parliament received by her as Clerk of the House of Commons le Bureau la liste des députés qui ont été proclamés élus au from and certified under the hand of Mr. -

Why Do Immigrants from Hong Kong to Canada Stay Or Leave?

WHY DO IMMIGRANTS FROM HONG KONG TO CANADA STAY OR LEAVE? Nuowen Deng B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2004 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Economics O Nuowen Deng 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Nuowen Deng Degree: M. A. (Economics) Title of Project: Why Do Immigrants From Hong Kong To Canada Stay Or Leave? Examining Committee: Chair: Ken Kasa Don Devoreb Senior Supervisor Alex Karaivanov Supervisor Steeve Mongrain Internal Examiner Date Approved: Tuesday, January 23,2007 .. 11 SIMON FRASER UNIVE~IW~ibrary DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http:llir.lib.sfu.calhandlell8921112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Summary by Quartile.Xlsx

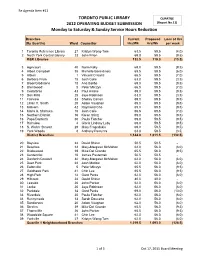

Re Agenda Item #11 TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY QUARTILE 2012 OPERATING BUDGET SUBMISSION (Report No.11) Monday to Saturday & Sunday Service Hours Reduction Branches Current Proposed Loss of Hrs (By Quartile) Ward Councillor Hrs/Wk Hrs/Wk per week 1 Toronto Reference Library 27 Kristyn Wong-Tam 63.5 59.5 (4.0) 2 North York Central Library 23 John Filion 69.0 59.5 (9.5) R&R Libraries 132.5 119.0 (13.5) 3 Agincourt 40 Norm Kelly 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 4 Albert Campbell 35 Michelle Berardinetti 65.5 59.5 (6.0) 5 Albion 1 Vincent Crisanti 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 6 Barbara Frum 15 Josh Colle 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 7 Bloor/Gladstone 18 Ana Bailão 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 8 Brentwood 5 Peter Milczyn 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 9 Cedarbrae 43 Paul Ainslie 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 10 Don Mills 25 Jaye Robinson 63.0 59.5 (3.5) 11 Fairview 33 Shelley Carroll 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 12 Lillian H. Smith 20 Adam Vaughan 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 13 Malvern 42 Raymond Cho 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 14 Maria A. Shchuka 15 Josh Colle 66.5 59.5 (7.0) 15 Northern District 16 Karen Stintz 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 16 Pape/Danforth 30 Paula Fletcher 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 17 Richview 4 Gloria Lindsay Luby 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 18 S. Walter Stewart 29 Mary Fragedakis 69.0 59.5 (9.5) 19 York Woods 8 AAnthonynthony Perruzza 63.0 59.5 ((3.5)3.5) District Branches 1,144.0 1,011.5 (132.5) 20 Bayview 24 David Shiner 50.5 50.5 - 21 Beaches 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 22 Bridlewood 39 Mike Del Grande 65.5 56.0 (9.5) 23 Centennial 10 James Pasternak 50.5 50.5 - 24 Danforth/Coxwell 32 Mary-Margaret McMahon 62.0 56.0 (6.0) 25 Deer Park 22 Josh Matlow 62.0 56.0 (6.0) -

While Every Effort Is Made to Ensure the Accuracy of the Contents

While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the contents of this site, users should be aware that due to circumstances beyond our control, it may be necessary to change the text of documents posted here and therefore no responsibility will be accepted by the Toronto Transit Commission for discrepancies which may occur between documents contained on this site and the formal hardcopy versions presented to the Commission. If it is necessary to rely on the accuracy of Commission documents the Office of the General Secretary should be contacted at 393-3698 to obtain a certifed copy. ONLY HARDCOPY RECORDS CERTIFIED BY THE GENERAL SECRETARY WILL BE DEEMED TO BE OFFICIAL. Form Revised: February 2005 TORONTO TRANSIT COMMISSION REPORT NO. MEETING DATE: March 21, 2007 SUBJECT: Membership – TTC Committees RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the Commission receive this report for information. DISCUSSION The attached provides a list of TTC Committees along with the membership for each Committee. - - - - - - - - - - - - March 2, 2007 1-16 Attachment TTC COMMITTEES TTC PROPERTY COMMITTEE Michael Thompson (Chair) Glenn De Baeremaeker Adam Giambrone Suzan Hall Peter Milczyn Anthony Perruzza TTC ADVERTISING REVIEW COMMITTEE Sandra Bussin Suzan Hall Anthony Perruzza Bill Saundercook (Committee Chair to be determined) TTC AUDIT COMMITTEE Bill Saundercook (Chair) Adam Giambrone Anthony Perruzza TTC BUDGET COMMITTEE Adam Giambrone Joe Mihevc Peter Milczyn Anthony Perruzza Bill Saundercook Michael Thompson (Committee Chair to be determined) TTC e-SYSTEM -

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on November 13, 2013 with amendments. City Council consideration on November 13, 2013 MM41.25 ACTION Amended Ward:All Requesting Mayor Ford to respond to recent events - by Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong, seconded by Councillor Peter Milczyn City Council Decision Caution: This is a preliminary decision. This decision should not be considered final until the meeting is complete and the City Clerk has confirmed the decisions for this meeting. City Council on November 13 and 14, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for misleading the City of Toronto as to the existence of a video in which he appears to be involved in the use of drugs. 2. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to co-operate fully with the Toronto Police in their investigation of these matters by meeting with them in order to respond to questions arising from their investigation. 3. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for writing a letter of reference for Alexander "Sandro" Lisi, an alleged drug dealer, on City of Toronto Mayor letterhead. 4. City Council request Mayor Ford to answer to Members of Council on the aforementioned subjects directly and not through the media. 5. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to take a temporary leave of absence to address his personal issues, then return to lead the City in the capacity for which he was elected. 6. City Council request the Integrity Commissioner to report back to City Council on the concerns raised in Part 1 through 5 above in regard to the Councillors' Code of Conduct. -

THE SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT of GROUNDWATER in CANADA the Expert Panel on Groundwater

THE SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF GROUNDWATER IN CANADA The Expert Panel on Groundwater Council of Canadian Academies Science Advice in the Public Interest Conseil des académies canadiennes THE SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF GROUNDWATER IN CANADA Report of the Expert Panel on Groundwater iv The Sustainable Management of Groundwater in Canada THE COUNCIL OF CANADIAN ACADEMIES 180 Elgin Street, Ottawa, ON Canada K2P 2K3 Notice: The project that is the subject of this report was undertaken with the approval of the Board of Governors of the Council of Canadian Academies. Board members are drawn from the RSC: The Academies of Arts, Humanities and Sciences of Canada, the Canadian Academy of Engineering (CAE) and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS), as well as from the general public. The members of the expert panel responsible for the report were selected by the Council for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. This report was prepared for the Government of Canada in response to a request from Natural Resources Canada via the Minister of Industry. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors – the Expert Panel on Groundwater. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication The sustainable management of groundwater in Canada [electronic resource] / Expert Panel on Groundwater Issued also in French under title: La gestion durable des eaux souterraines au Canada. Includes bibliographical references. Issued also in print format ISBN 978-1-926558-11-0 1. Groundwater--Canada--Management. 2. Groundwater-- Government policy--Canada. 3. Groundwater ecology--Canada. 4. Water quality management--Canada. I. Council of Canadian Academies.