Obesity and Chronic Inflammation in Phlebological and Lymphatic Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Report of Chronic Sclerosing Panniculitis Hadiuzzaman*, M

Journal of Pakistan Association of Dermatologists 2010; 20 : 246-248. Case Report A case report of chronic sclerosing panniculitis Hadiuzzaman*, M. Hasibur Rahman*, Nazma Parvin Ansari**, Aminul Islam† *Department of Dermatology, Community Based Medical College, Bangladesh, Mymensingh, Bangladesh. **Department of Pathology, Community Based Medical College, Bangladesh, Mymensingh, Bangladesh †Department of Medicine, Community Based Medical College, Bangladesh, Mymensingh, Bangladesh Abstract Sclerosing panniculitis is a fibrotic process that usually occurs on the legs, commonly in women older than 40. The principal features are indurated woody plaques with erythema, edema, telangiectasia, and hyperpigmentation. Although the exact pathogenesis is uncertain, it is thought to occur as a result of ischemic changes. We present a 28-year-old married female who had a 10- year history of painful sclerotic plaques, repeated ulceration and healing with fibrosis of the both lower legs and abdomen. Venogram and Doppler investigations were normal. Skin biopsy from the edge of the ulcer demonstrated the feature of chronic sclerosing panniculitis. Satisfactory improvement was found with methotrexate 7.5mg weekly for 4 months. No recurrence was noted within 1 year follow up. Key words Sclerosing panniculitis, lipodermatosclerosis. Case report Mild swelling of the legs worse at the end of the day was also reported. Tenderness of the ulcer A 28-year-old married female presented to was worse with dependency. There was no dermatology outpatient, Community Based history of previous trauma to the area, joint Medical College, Bangladesh, with a 10-year complaint, pancreatic disease, or other tender history of painful repeated ulceration and nodular lesions or ulcerations. There was no healing with fibrosis of the both lower legs and significant history of fever and night sweating. -

2016 Essentials of Dermatopathology Slide Library Handout Book

2016 Essentials of Dermatopathology Slide Library Handout Book April 8-10, 2016 JW Marriott Houston Downtown Houston, TX USA CASE #01 -- SLIDE #01 Diagnosis: Nodular fasciitis Case Summary: 12 year old male with a rapidly growing temple mass. Present for 4 weeks. Nodular fasciitis is a self-limited pseudosarcomatous proliferation that may cause clinical alarm due to its rapid growth. It is most common in young adults but occurs across a wide age range. This lesion is typically 3-5 cm and composed of bland fibroblasts and myofibroblasts without significant cytologic atypia arranged in a loose storiform pattern with areas of extravasated red blood cells. Mitoses may be numerous, but atypical mitotic figures are absent. Nodular fasciitis is a benign process, and recurrence is very rare (1%). Recent work has shown that the MYH9-USP6 gene fusion is present in approximately 90% of cases, and molecular techniques to show USP6 gene rearrangement may be a helpful ancillary tool in difficult cases or on small biopsy samples. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors, 5th edition. Mosby Elsevier. 2008. Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, Roth CW, Seys AR, Jin L, Ye Y, Lau AW, Wang X, Oliveira AM. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011 Oct;91(10):1427-33. Amary MF, Ye H, Berisha F, Tirabosco R, Presneau N, Flanagan AM. Detection of USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis: an important diagnostic tool. Virchows Arch. 2013 Jul;463(1):97-8. CONTRIBUTED BY KAREN FRITCHIE, MD 1 CASE #02 -- SLIDE #02 Diagnosis: Cellular fibrous histiocytoma Case Summary: 12 year old female with wrist mass. -

Panniculitis Martin C

Panniculitis Martin C. Mihm M.D. Director – Mihm Cutaneous Pathology Consultative Service (MCPCS) Brigham and Women’s Hospital Director – Melanoma Program Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School Co-Director – Melanoma Program Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School Conflicts of Interest • Chairman Scientific Advisory Board – Caliber I.D. Inc. • Member Scientific Advisory Board – MELA Sciences Inc. • Consultant – Novartis • Consultant – Alnylam Disorders of the Subcutis • Septal • Lobular • Mixed • Inflammatory (N/G/L) • Pauci-inflammatory 1 Septal Panniculitis • Erythema nodosum • Necrobiosis lipoidica • Morphea profundus Erythema Nodosum Clinical Features • Young adults • Nodular or plaque like lesions • Anterior aspect of lower legs (common) • Arms or abdomen (occurs occasionally) • Clinical course • Initially erythematous, painful area • Evolves into nodule or plaque • Lasts 10 days to 8 weeks • Fever, malaise, arthralgias (variable s/s) Erythema Nodosum Clinical Features Causation • Systemic diseases: CTD, Behcet’s, Sweet’s, sarcoidosis,etc. • Drugs: Numerous drugs have been associated: penicillin, sulfa, Cipro, isotretinoin, etc. • 30%: idiopathic or of unknown cause.. 2 3 Erythema nodosum : Well Developed Lesion • Septal fibrosis • Septal chronic inflammation • Lymphocytes • Frank Vasculitis may not be present • Granulomatous changes • Small granulomatous aggregates of histiocytes • Miescher’s radial granuloma • Multinucleated giant cells 4 5 6 Erythema nodosum : Morphologic Clues to underlying etiology -

100 CASES in Dermatology This Page Intentionally Left Blank 100 CASES in Dermatology

100 CASES in Dermatology This page intentionally left blank 100 CASES in Dermatology Rachael Morris-Jones PhD PCME FRCP Consultant Dermatologist & Honorary Senior Lecturer, King’s College Hospital, London, UK Ann-Marie Powell Consultant Dermatologist, Department of Dermatology, St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK Emma Benton MB ChB MRCP Post-CCT Clinical Research Fellow, St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust, London, UK 100 Cases Series Editor: Professor P John Rees MD FRCP Dean of Medical Undergraduate Education, King’s College London School of Medicine at Guy’s, King’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals, London, UK First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Hodder Arnold, an imprint of Hodder Education, a division of Hachette UK 338 Euston Road, London NW1 3BH http://www.hodderarnold.com © 2011 Rachael Morris-Jones, Ann-Marie Powell and Emma Benton All rights reserved. Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form, or by any means with prior permission in writing of the publishers or in the case of reprographic production in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. In the United Kingdom such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency: Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS Hachette UK’s policy is to use papers that are natural, renewable and recyclable products and made from wood grown in sustainable forests. The logging and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

Consultations in Medical Dermatology Joseph L

Consultations In Medical Dermatology Joseph L. Jorizzo, MD Professor of Clinical Dermatology Weill Cornell Medical College New York, NY Professor, Founder and Former Chair Department of Dermatology Wake Forest School of Medicine Winston-Salem, NC Conflict of Interest Advisory Boards/Honoraria Amgen Leo Pharmaceuticals Quote from an anonymous patient: “What I am told on the first visit is patient education – on the second an excuse.” Possibilities for a patient who presents with a complex medical dermatosis and systemic signs and symptoms: 1. Clinicopathologic diagnosis of dermatosis integrates all findings eg. Sarcoidosis – skin, eye, lungs, etc 2. Clinicopathologic diagnosis reveals a reactive dermatosis – communication with internist or pediatrician will outline underlying medical conditions eg. Vasculitis 3. No direct relationship – eg. Scabies/Fibromyalgia Patients wishes to know from the internet whether they need x or y therapy for their presumptive diagnosis. Instead it is important to not let the patient “drive” for their own benefit. Step 1. – Clinicopathologic diagnosis- Caution influence of therapy on biopsy and clinical appearance Step 2. – Assess the extent (internal manifestations of disease) Step 3. – Assess for etiology Step 4. - Therapeutic ladder Lichen Planus Key Features • Idiopathic, inflammatory disease of the skin, hair, nails and mucous membranes, seen most commonly in middle-aged adults • Flat-topped violaceous papules and plaques favoring the wrists, forearms, genitalia, distal lower extremities and presacral -

Chronic Venous Insufficiency in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Positive Patients Undergoing Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy

Journal of Phlebology and Lymphology Chronic Venous Insufficiency in Human Immunodeficiency Virus- Positive Patients Undergoing Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Authors: Marcelo Burihan Calil, MD1, Andre Fonseca Duarte, MD2, Catherine Puliti Hermida Reigada, MD3, Adnan Neser, MD1, Felipe Nasser, MD1, Jose Carlos Ingrund, MD1, Viviane de Almeida Jabur, MD4, Patrícia Carla Piragibe Ramos Burihan, MD4, Gilberto Mitsuo Ukita, PhD2 Adress:1 Santa Marcelina Hospital, 2 University of São Paulo, 3 University of Campinas, 4 University of Santo Amaro E-mail: [email protected] *corresponding author Published: april 2011 Received: 16 November 2011 Journal Phlebology and Lymphology 2011; 4:21-30 Accepted: 12 December 2011 Abstract Introduction: The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a chronic and progressive disease with an important worldwide epidemiological impact. Likewise, chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) also represents an extremely relevant pathology. There are no studies correlating both of them. Aim: Characterize human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive patients undergoing highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) as to the presence of varicose veins and CVI of the lower limbs. Method: A descriptive transversal study. 106 HIV positive patients were evaluated. The majority of the patients were assisted in an infectious disease clinic. The non-parametric test of association qui-square (X2) was used. Results:The time of HIV infection was significant associated with the symptom cramps (P = 0.049). The time of HAART showed a significant association in relation to tingling sensation (P= 0.048). Regarding the time of use of zidovudine, a significant association was observed with tingling sensation (P< 0.01) and edema (P= 0.017). A significant association with referred edema (P= 0.016) was also shown. -

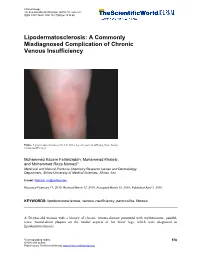

Lipodermatosclerosis: a Commonly Misdiagnosed Complication of Chronic Venous Insufficiency

Clinical Image TheScientificWorldJOURNAL (2010) 10, 576–577 ISSN 1537-744X; DOI 10.1100/tsw.2010.60 Lipodermatosclerosis: A Commonly Misdiagnosed Complication of Chronic Venous Insufficiency Figure. Lipodermatosclerosis on the left lower leg of a patient suffering from chronic venous insufficiency. Mohammad Kazem Fallahzadeh, Mohammad Khalesi, and Mohammad Reza Namazi* Medicinal and Natural Products Chemistry Research Center and Dermatology Department, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Received February 11, 2010; Revised March 12, 2010; Accepted March 15, 2010; Published April 1, 2010 KEYWORDS: lipodermatosclerosis, venous insufficiency, panniculitis, fibrosis A 50-year-old woman with a history of chronic venous disease presented with erythematous, painful, tense, bound-down plaques on the medial aspects of her lower legs, which were diagnosed as lipodermatosclerosis. *Corresponding author. 576 ©2010 with author. Published by TheScientificWorld; www.thescientificworld.com Fallahzadeh et al.: Lipodermatosclerosis TheScientificWorldJOURNAL (2010) 10, 576–577 Lipodermatosclerosis is a complication of severe chronic venous insufficiency that results from high venous pressure and resulting increased capillary permeability, perivascular fibrin cuffing, and tissue hypoxia. These events culminate in fibrosis and membranous fat necrosis[1]. Lipodermatosclerosis can present as painful, red, indurated plaques that may be easily misdiagnosed as cellulitis, thrombophlebitis, and morphea[2]. It initially develops on the medial aspect of the ankle and then spreads to involve the entire leg circumferentially[3]. In its advanced states, lipodermatosclerosis, along with a lymphedematous upper portion of the leg and an edematous foot, can look like an inverted champagne bottle[3]. Compression therapy, drugs such as stanozolol, and surgical procedures are the current therapeutic options available for this recalcitrant conundrum[2]. -

Current Concepts in Dermatology

CURRENT CONCEPTS IN DERMATOLOGY RICK LIN, D.O., FAOCD PROGRAM CHAIR Faculty Suzanne Sirota Rozenberg, DO, FAOCD Dr. Suzanne Sirota Rozenberg is currently the program director for the Dermatology Residency Training Program at St. John’s Episcopal Hospital in Far Rockaway, NY. She graduated from NYCOM in 1988, did an Internship and Family Practice residency at Peninsula Hospital Center and a residency in Dermatology at St. John’s Episcopal Hospital. She holds Board Certifications from ACOFP, ACOPM – Sclerotherapy and AOCD. Rick Lin, DO, FAOCD Dr. Rick Lin is a board-certified dermatologist practicing in McAllen, TX since 2006. He is the only board-certified Mohs Micrographic Surgeon in the Rio Grande Valley region. Dr. Rick Lin earned his Bachelor degree in Biology at the University of California at Berkeley and received his medical degree from University of North Texas Health Science Center at Fort Worth in 2001. He also graduated with the Master in Public Health Degree at the School of Public Health of the University of North Texas Health Science Center. He then completed a traditional rotating internship at Dallas Southwest Medical Center in 2002. In 2005 he completed his Dermatology residency training at the Northeast Regional Medical Center in Kirksville, Missouri in conjunction with the Dermatology Institute of North Texas. Dr. Rick Lin served as the Chief Resident of the residency training program for two years. He was also the Resident Liaison for the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology for two years prior to the completion of his residency. In addition to general dermatology and dermatopathology, Dr. Lin received specialized training in Mohs Micrographic surgery, advanced aesthetic surgery, and cosmetic dermatology. -

Severity Stratification by Compression Ultrasound Examination in Lipodermatosclerosis and Diabetic Dermopathy Patients: a Report of Three Cases

CASE SERIES DERMATOLOGY // IMAGING Severity Stratification by Compression Ultrasound Examination in Lipodermatosclerosis and Diabetic Dermopathy Patients: a Report of Three Cases Cristian Podoleanu1, Bogdan Dobrovat2, Simona Stolnicu3,4, Anca Chiriac5,6,7 1 Department of Internal Medicine, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Tîrgu Mureș, Romania 2 "Gr.T. Popa" University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iași, Romania 3 Department of Pathology, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Tîrgu Mureș, Romania 4 Histopat-Invest Laboratory, Tîrgu Mureș, Romania 5 Apollonia University, Department of Dermatology, Iași, Romania 6 “Petru Poni” Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the Romanian Academy, Iași, Romania 7 Nicolina Medical Center, Iași, Romania CORRESPONDENCE ABSTRACT Cristian Podoleanu Lipodermatosclerosis and diabetic dermopathy are low-risk skin lesions with many similar Str. Gheorghe Marinescu nr. 38 clinical features, except for venous abnormalities such as chronic venous insufficiency, but 540099 Tîrgu Mureș, Romania are rarely a reason for referring the patient to vascular ultrasound examination. We present 3 Tel: +40 744 573 784 serial cases in which the compression ultrasound examination (CUS) of the venous circulation E-mail: [email protected] of the affected limbs was of utmost importance in the severity stratification. Asymptomatic deep venous thrombosis (DVT) was found in the first two cases, while in the third case the ARTICLE HISTORY CUS excluded any type of vascular involvement, leading to a definite diagnosis of diabetic dermopathy. Lipodermatosclerosis may be associated with asymptomatic DVT due to chronic Received: 19 March, 2017 venous insufficiency, and early referral to CUS positively impacts further patient management. Accepted: 27 May, 2017 Keywords: lipodermatosclerosis, diabetic dermopathy, compression ultrasound, severity strat- ification INTRODUCTION Asymptomatic deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and its related disorder, venous thromboembolism (VTE), are major health care challenges: VTE is the 3rd Bogdan Dobrovat • Str. -

Lipodermatosclerosis

LIPODERMATOSCLEROSIS http://www.aocd.org Lipodermatosclerosis, also known as sclerosing panniculitis and hypodermitis sclerodermiformis, is an inflammation of the subcutaneous fat, often associated with chronic venous insufficiency. Lipodermatosclerosis is classically found on the inner aspect of the lower extremities above the ankle. It is classified into acute and chronic phases. The acute phase presents clinically as pain, redness, warmth, and tenderness. The chronic, fibrotic phase, presents as red-brown to violet-brown discoloration with firmness and atrophy often appearing as an inverted “champagne bottle.” Lipodermatosclerosis is most commonly found in people with underlying poor circulation in the legs. It is often seen in women over the age of 40 years and men over the age of 70 years. Risk factors include age, immobility, obesity, smoking, family history, and history of deep vein thrombosis or trauma to the venous system. The exact cause is unknown, but evidence suggest that venous hypertension resulting in increased capillary permeability leads to leakage of fibrinogen and white blood cells into the dermis. The fibrinogen forms fibrin cuffs around capillaries, which impedes the exchange of oxygen. This process ultimately causes hypoxia, resulting in venous ulceration. Lipodermatosclerosis is often misdiagnosed as cellulitis. Diagnosis of Lipodermatosclerosis can be done clinically as it does not require biopsy. In fact, biopsy is not advised due to the concern for poor wound healing and the likelihood to develop chronic ulcers. Lipodermatosclerosis is best treated with conservative management. This includes leg elevation, compression stockings, lifestyle modifications (increased physical activity and weight loss, smoking cessation). Physical therapy using ultrasound has been reported as helpful. -

Painful Subcutaneous Nodules of the Lower Extremities

CCOSMETIASE REPOC TRETCHNIQUE Painful Subcutaneous Nodules of the Lower Extremities Michael Kassardjian, MS-IV; Saira B. Momin, DO; James Q. Del Rosso, DO; Narciss Mobini, MD Painful subcutaneous nodules of the lower extremities are dermatologic manifestations that may be associated with multiple underlying etiologies. Various infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders, and physical and chemical agents may precipitate such a clinical presentation. Keeping the differ- ential diagnosis in mind, appropriate medical workup is essential to accurately diagnose and treat underlying disorders. ainful subcutaneousCOS nodules of the lower DERM patient reported sometimes having symptoms of pruritus extremities are cutaneous processes that tend along with a burning sensation. The patient had a medi- to be attributed to a variety of underlying cal history of hypothyroidism. medical conditions. Infectious diseases, sar- Physical examination revealed tender, indurated, ery- coidosis, reactions to medications, autoim- thematous to hyperpigmented nodules on the left lower Pmune disorders, and malignanciesDo are someNot examples of extremity Copy with evidence of edema and varicose veins underlying disorders that may simulate such a clinical (Figure 1). a 5-mm punch biopsy specimen revealed presentation. a clearly definable cause may be deter- dermal sclerosis with compact eosinophilic collagen mined by generating a complete differential diagnosis, bundles and slight thickening of subcutaneous septae which is necessary for proper workup and effective man- with sparing of the overlying epidermis (Figure 2a). The agement of potentially serious underlying conditions. subcutaneous tissue exhibited microcyst, lipomembra- nous changes, and evidence of fat necrosis. Blood vessels CASE REPORT were thickened with an area of calcification and mild a 66-year-old white woman presented with pain in the superficial perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes also left lower extremity of 1 years’ duration. -

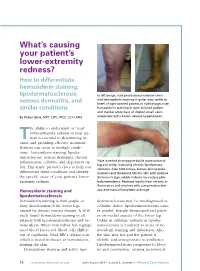

How to Differentiate Hemosiderin Staining

What’s causing your patient’s lower-extremity redness? How to differentiate hemosiderin staining, lipodermatosclerosis, In left image, note pronounced varicose veins and hemosiderin staining in gaiter area (ankle to venous dermatitis, and knee) of light-skinned patient. In right image, note similar conditions hemosiderin staining in dark-skinned patient and medial ankle flare of dilated small veins By Robyn Bjork, MPT, CWS, WCC, CLT-LANA associated with chronic venous hypertension. he ability to understand or “read” lower-extremity redness in your pa - Ttient is essential to determining its cause and providing effective treatment. Redness can occur in multiple condi - tions—hemosiderin staining, lipoder - matosclerosis, venous dermatitis, chronic inflammation, cellulitis, and dependent ru - Note inverted champagne-bottle appearance of bor. This article provides clues to help you leg and ankle, indicating chronic lipodermato - sclerosis. Also note lumpy, bumpy skin (papillo - differentiate these conditions and identify matosis) and thickened, fibrotic skin with positive the specific cause of your patient’s lower- Stemmer’s sign, which indicate secondary phle - extremity redness. bolymphedema. Redness results from chronic in - flammation and resolves with compression ther - Hemosiderin staining and apy and manual lymphatic drainage. lipodermatosclerosis Hemosiderin staining is dark purple or dermatosclerosis may be misdiagnosed as rusty discoloration of the lower legs cellulitis. Active lipodermatosclerosis caus - caused by chronic venous disease. A 2010 es painful, sharply demarcated red patch - study found hemosiderin staining in all es on medial aspects of the lower leg. subjects with lipodermatosclerosis and ve - Unlike in cellulitis, redness in lipoder - nous ulcers. When vein valves fail, regurgi - matosclerosis is localized to areas of he - tated blood forces red blood cells (RBCs) mosiderin staining and induration.