Coulon 2018 Mres Theconfeder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded4.0 License

New West Indian Guide 94 (2020) 39–74 nwig brill.com/nwig A Disagreeable Text The Uncovered First Draft of Bryan Edwards’s Preface to The History of the British West Indies, c. 1792 Devin Leigh Department of History, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA [email protected] Abstract Bryan Edwards’s The History of the British West Indies is a text well known to histori- ans of the Caribbean and the early modern Atlantic World. First published in 1793, the work is widely considered to be a classic of British Caribbean literature. This article introduces an unpublished first draft of Edwards’s preface to that work. Housed in the archives of the West India Committee in Westminster, England, this preface has never been published or fully analyzed by scholars in print. It offers valuable insight into the production of West Indian history at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, it shows how colonial planters confronted the challenges of their day by attempting to wrest the practice of writing West Indian history from their critics in Great Britain. Unlike these metropolitan writers, Edwards had lived in the West Indian colonies for many years. He positioned his personal experience as being a primary source of his historical legitimacy. Keywords Bryan Edwards – West Indian history – eighteenth century – slavery – abolition Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies is a text well known to scholars of the Caribbean (Edwards 1793). First published in June of 1793, the text was “among the most widely read and influential accounts of the British Caribbean for generations” (V. -

Click Here to Download

The Project Gutenberg EBook of South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I, by J. Castell Hopkins and Murat Halstead This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I Comprising a History of South Africa and its people, including the war of 1899 and 1900 Author: J. Castell Hopkins Murat Halstead Release Date: December 1, 2012 [EBook #41521] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SOUTH AFRICA AND BOER-BRITISH WAR *** Produced by Al Haines JOSEPH CHAMBERLAIN, Colonial Secretary of England. PAUL KRUGER, President of the South African Republic. (Photo from Duffus Bros.) South Africa AND The Boer-British War COMPRISING A HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA AND ITS PEOPLE, INCLUDING THE WAR OF 1899 AND 1900 BY J. CASTELL HOPKINS, F.S.S. Author of The Life and Works of Mr. Gladstone; Queen Victoria, Her Life and Reign; The Sword of Islam, or Annals of Turkish Power; Life and Work of Sir John Thompson. Editor of "Canada; An Encyclopedia," in six volumes. AND MURAT HALSTEAD Formerly Editor of the Cincinnati "Commercial Gazette," and the Brooklyn "Standard-Union." Author of The Story of Cuba; Life of William McKinley; The Story of the Philippines; The History of American Expansion; The History of the Spanish-American War; Our New Possessions, and The Life and Achievements of Admiral Dewey, etc., etc. -

PUBLICATION No. 38 MARCH, 1978 THOMAS MEIKLE, 1862-1939

PUBLICATION No. 38 MARCH, 1978 THOMAS MEIKLE, 1862-1939 The founder of the Meikle Organisation sailed from Scotland with his parents in 1869. The family settled in Natal where Thomas and his brothers John and Stewart gained their first farming ex perience. In 1892 the three brothers set off for Rhodesia with eight ox- wagons. Three months later they had completed the 700 mile trek to Fort Victoria. Here they opened a store made of whisky cases and roofed over with the tarpaulins that had covered their wagons. Progress was at first slow, nevertheless, branches were opened in Salisbury in 1893, Bulawayo and Gwelo in 1894, and in Umtali in 1897. From these small beginnings a vast network of stores, hotels, farms, mines and auxilliary undertakings was built up. These ventures culminated in the formation of the Thomas Meikle Trust and Investment Company in 1933. The success of these many enterprises was mainly due to Thomas Meikle's foresight and his business acumen, coupled with his ability to judge character and gather around him a loyal and efficient staff. His great pioneering spirit lives on: today the Meikle Organisation is still playing an important part in the development of Rhodesia. THOMAS MEIKLE TRUST AND INVESTMENT CO. (PVT.) LIMITED. Travel Centre Stanley Avenue P.O. Box 3598 Salisbury Charter House, at the corner of Jameson Avenue and Kings Crescent, was opened in 1958. The name Charter House was given by The British South Africa Company to its administrative offices. It is now the headquarters of the Anglo American Corporation Group in Rhodesia. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

Redescription of Hypoatherina Valenciennei and Its Relationships to Other Species of Atherinidae in the Pacific and Indian Oceans

Japanese Journal of Ichthyology 魚 類 学 雑 誌 Vol. 35, No. 2 1988 35 巻 2 号 1988年 Redescription of Hypoatherina valenciennei and its Relationships to Other Species of Atherinidae in the Pacific and Indian Oceans Walter Ivantsoff and Maurice Kottelat (Received December 23, 1986) Abstract A review of Tirant's collections and examination of types has resulted in the reidentifica- tion of Haplocheilus argyrotaenia Tirant as Hypoatherina valenciennei (Bleeker) which is found throughout the southwestern Pacific and as far north as Japan. The taxonomic status of H. valenciennei is clarified and Bleeker's emendation of the original specific epithet valenciennei to valenciennesi is rejected. The systematic position of this species is difficult to determine since H. valenciennei shows affinities with both Hypoatherina and Atherinomorus. In the light of the present knowledge, Bleeker's species appears to have greater affinities with Hypoatherina and is therefore placed in this genus. Recent reexamination of the types of Haplo- 1983). The genus Hypoatherina as defined by cheilus argyrotaenia Tirant, 1883, (unaccepted and Ivantsoff (1978) includes all those species with misspelt emendation of Haplochilus Agassiz, 1846, moderately long dorsal process of premaxilla but for Aplocheilus McClelland, 1839) has prompted not longer than eye diameter, lateral process of us to review the status of Hypoatherina valenciennei premaxilla short and broad, lower jaw coronoid (Bleeker, 1853a) which is considered to be the process highly elevated, distinct notch (sensory senior synonym of Tirant's species (thought by canal opening) in posterior margin of anterior him to be an aplocheilid). Although the systema- bony edge of preopercle near its lower corner, tic position of the Pacific atherinids is yet to be body slender and subcylindrical, midlateral band resolved, work to that end has already begun. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

Final Report Anguilla General Election

ANGUILLA GENERAL ELECTION JUNE 2020 CPA BIMR ELECTION EXPERT MISSION FINAL REPORT CPA BIMR Election Expert Mission Final Report CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 INTRODUCTION TO THE MISSION 3 BACKGROUND 4 COVID-19 PANDEMIC 4 LEGAL FRAMEWORK 5 ELECTORAL SYSTEM 7 BOUNDARY DELIMITATION 7 THE RIGHT TO VOTE 9 VOTER REGISTRATION 10 ELECTION ADMINISTRATION 11 TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION 13 THE RIGHT TO STAND FOR ELECTION 13 CANDIDATE REGISTRATION 14 ELECTION CAMPAIGN 15 CAMPAIGN FINANCE 15 MEDIA 16 PARTICIPATION OF WOMEN 17 PARTICIPATION OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES 17 ELECTORAL JUSTICE 18 ELECTION DAY 18 ADVANCE VOTING 18 VOTING 19 ELECTION RESULTS 20 RECOMMENDATIONS 21 1 CPA BIMR Election Expert Mission Final Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association British Islands and Mediterranean Region (CPA BIMR) conducted a virtual Election Expert Mission to the Anguilla General Elections in June 2020. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, research was carried out online, and interviews with a wide range of stakeholders were conducted utilising digital meeting platforms. • Due to Covid-19 restrictions, political parties and candidates could not convene campaign events until 5 June. The Supervisor of Elections was also unable to conduct some planned voter education activities. The election took place on 29 June. As Anguilla had been virus-free for over two weeks by then, social distancing or other public health measures were not required during polling and counting. • The conduct of elections in Anguilla was broadly in compliance with the human rights standards and universal principles that are applicable. The right of political participation was well-respected, with the principal exception being the absence of equality in the weight of the vote as there were vast differences in district size. -

American Eel Anguilla Rostrata

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the American Eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 71 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge V. Tremblay, D.K. Cairns, F. Caron, J.M. Casselman, and N.E. Mandrak for writing the status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair (Freshwater Fishes) COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. Funding for this report was provided by Environment Canada. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’anguille d'Amérique (Anguilla rostrata) au Canada. Cover illustration: American eel — (Lesueur 1817). From Scott and Crossman (1973) by permission. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/458-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43225-8 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name American eel Scientific name Anguilla rostrata Status Special Concern Reason for designation Indicators of the status of the total Canadian component of this species are not available. -

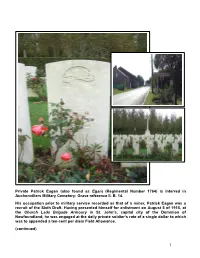

Private Patrick Eagan (Also Found As Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) Is Interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave Reference II

Private Patrick Eagan (also found as Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) is interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave reference II. B. 14. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a miner, Patrick Eagan was a recruit of the Sixth Draft. Having presented himself for enlistment on August 5 of 1915, at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland, he was engaged at the daily private soldier’s rate of a single dollar to which was to appended a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. (continued) 1 Just one day after having enlisted, on August 6 he was to return to the CLB Armoury on Harvey Road. On this second occasion Patrick Eagan was to undergo a medical examination, a procedure which was to pronounce him as being…Fit for Foreign Service. And it must have been only hours afterwards again that there then came the final formality of his enlistment: attestation. On the same August 6 he pledged his allegiance to the reigning monarch, George V, at which moment Patrick Eagan thus became…a soldier of the King. A further, and lengthier, waiting-period was now in store for the recruits of this draft, designated as ‘G’ Company, before they were to depart from Newfoundland for…overseas service. Private Eagan, Regimental Number 1764, was not to be again called upon until October 27, after a period of twelve weeks less two days. Where he was to spend this intervening time appears not to have been recorded although he possibly returned temporarily to his work and perhaps would have been able to spend time with family and friends in the Bonavista Bay community of Keels – but, of course, this is only speculation. -

American Eel (Anguilla Rostrata )

American Eel (Anguilla rostrata ) Abstract The American eel ( Anguilla rostrata ) is a freshwater eel native in North America. Its smooth, elongated, “snake-like” body is one of the most noted characteristics of this species and the other species in this family. The American Eel is a catadromous fish, exhibiting behavior opposite that of the anadromous river herring and Atlantic salmon. This means that they live primarily in freshwater, but migrate to marine waters to reproduce. Eels are born in the Sargasso Sea and then as larvae and young eels travel upstream into freshwater. When they are fully mature and ready to reproduce, they travel back downstream into the Sargasso Sea,which is located in the Caribbean, east of the Bahamas and north of the West Indies, where they were born (Massie 1998). This species is most common along the Atlantic Coast in North America but its range can sometimes even extend as far as the northern shores of South America (Fahay 1978). Context & Content The American Eel belongs in the order of Anguilliformes and the family Anguillidae, which consist of freshwater eels. The scientific name of this particular species is Anguilla rostrata; “Anguilla” meaning the eel and “rostrata” derived from the word rostratus meaning long-nosed (Ross 2001). General Characteristics The American Eel goes by many common names; some names that are more well-known include: Atlantic eel, black eel, Boston eel, bronze eel, common eel, freshwater eel, glass eel, green eel, little eel, river eel, silver eel, slippery eel, snakefish and yellow eel. Many of these names are derived from the various colorations they have during their lifetime. -

Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong By

Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong by Cecilia Louise Chu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor C. Greig Crysler Professor Eugene F. Irschick Spring 2012 Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Copyright 2012 by Cecilia Louise Chu 1 Abstract Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Cecilia Louise Chu Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair This dissertation traces the genealogy of property development and emergence of an urban milieu in Hong Kong between the 1870s and mid 1930s. This is a period that saw the transition of colonial rule from one that relied heavily on coercion to one that was increasingly “civil,” in the sense that a growing number of native Chinese came to willingly abide by, if not whole-heartedly accept, the rules and regulations of the colonial state whilst becoming more assertive in exercising their rights under the rule of law. Long hailed for its laissez-faire credentials and market freedom, Hong Kong offers a unique context to study what I call “speculative urbanism,” wherein the colonial government’s heavy reliance on generating revenue from private property supported a lucrative housing market that enriched a large number of native property owners. Although resenting the discrimination they encountered in the colonial territory, they were able to accumulate economic and social capital by working within and around the colonial regulatory system. -

Mcmurdo of the Schooner 'Stanley'

McMurdo of the Schooner 'Stanley' PART II by WILFRED FOWLER [In the previous issue of Queensland Heritage (vol. I, no. 8, pp. 3-15) been making a friendly visit to the Stanley were seized to be held as the first part of Mr Fowler's article was published. The article recounts hostages. though through the carelessness of the guards these prisoners the voyage of the lIS-ton Pacific Island Labour vessel Stanley, which escaped. Ultimately, after threats of personal violence were made by left Maryborough, Queensland, on 31 March 1883 with Captain Davies McMurdo against the natives, twelve of the thirteen original recruits in command. His first voyage in the labour trade, he had been licensed were handed over. The thirteenth man was considered medically unfit. to recruit 98 labourers. The crew consisted of William Connell, the The Stanley then set sail for New Britain and New Ireland and late first mate; Sydney Gerrans, the second mate; Daniel Moussue, cook and in April was brought to anchor at Mioko in St. Georges Channel, which steward; four A.Bs., Adams, Austin, Rowan and Chaillon; and eight separates New Britain from New Ireland. natives. William Anastasias McMurdo had been appointed as Government Davies went off in search of interpreters while McMurdo went to see Agent to accompany them to see that the provisions of the Pacific Islands Hernsheim, a German trader at Matupi near Rabaul on the New Britain Labourers Act of 1880 were complied with. On 10 April they anchored mainland to report the trouble they had encountered with German Charley.