The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inspirations from Europe's Leading Architects

SHADES OF WHITE Inspirations from Europe’s leading architects. DEAR BAUMIT FRIENDS AND PARTNERS, It has been almost 10 years since However, white on a facade not only has an aesthetic reason, We were inspired Baumit created Europe’s largest but also a very tangible one: climate change. Temperatures facade colour system, Baumit Life, are rising, our cities are getting hotter and hotter. The albedo by the idea with 888 unique colour shades. effect or the reflective power of the colour white can effectively Even though the trend-barometer counteract overheating in certain regions. We want to make has taken a turn in a more purist more use of this effect. of richness and variety direction, there remain a multitu- de of possibilities. In this book, renowned architects from our 25 Baumit countries of one colour tone answer questions such as “Why do architects wear black and In this book, and with our latest build white?” Their surprising answers and many insights into Baumit colour-coup, we take a the international world of architecture can be found on the when we created look at the colour that is the sum following pages. of all colours of the rainbow: the colour white. The Inuit tribe uses the Baumit colour series a variety of different names for white, depending on the colour Enjoy browsing and perusing! and texture. We were inspired by this idea of richness and variety “12 Shades of White”. of one colour tone when we created the Baumit colour series Sincerely, “Shades of White”. It is dedicated above all to our design specia- lists, the architects, for whom white has always been a popular colour choice. -

The Devil's Colors

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs The Devil’s Colors: A Comparative Study of French and Nigerian Folktales Journal Item How to cite: Ugochukwu, Francoise (2007). The Devil’s Colors: A Comparative Study of French and Nigerian Folktales. Oral Tradition, 21(2) pp. 250–268. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2007 Center for Studies in Oral Tradition Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1353/ort.2007.0005 http://journal.oraltradition.org/issues/21ii Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Oral Tradition, 21/2 (2006): 250-268 The Devil’s Colors: A Comparative Study of French and Nigerian Folktales Françoise Ugochukwu Introduction In the concluding chapter of her book on race in African oral literature, Veronika Görög-Karady (1976:245) remarks that “the main difficulty is to find the precise meaning of color oppositions, valorization or depreciation in African cultures.” This study, mainly based on five separate published collections by Joisten (1965, 1971, 1977, 1996) and the author (1992), will compare French and Nigerian folktales, focusing on French Dauphiné and Nigerian Igboland,1 in order to consider the role color plays in encounters with supernatural characters, revealing a complex network of correspondences that serve as a tool to communicate color-coded values. -

New Varieties

NEW2021 VARIETIES AUTUMN INFERNO® COTONEASTER Cotoneaster ‘Bronfire’ PP30,493 USDA Hardiness Zone: 5 AHS Heat Zone: 7 Height: 5-6’ Spread: 4-5’ Exposure: Full Sun to Part Shade Shape: Upright- Arching Discovered at Bron & Sons Nursery in British Columbia, this new Cotoneaster is a natural cross between C. lucidus and C. apiculatus. It has many of the attributes of C. lucidus that we so love for a hedge - great form, easily pruned, great foliage all season long plus great fall color. But what we really love about Autumn Inferno® is the small red berries formed along the stems in fall. The berries stay on the plant until the birds come and take them, no mess involved. Perfect as a pruned formal hedge or let it go natural. Just enough height to block off your annoying neighbors. FIRSTEDITIONSPLANTS.COM Plant patent has been applied for and trademark has been declared. Propagation and/or use of trademark without license is prohibited. GALACTIC PINK® CHASTETREE Vitex agnus-castus ‘Bailtextwo’ PP30,852 USDA Hardiness Zone: 6 AHS Heat Zone: 9 Height: 6-8’ Spread: 6-8’ Exposure: Full Sun Shape: Upright - Rounded Galactic Pink® has flowers that are a beautiful shade of pink and intermediate in size. The fragrant flowers, born in longGalactic panicles, Pink® bloomhas flowers from Junethat areto Octobera beautiful and shade attract of pollinatorspink and intermediate by the dozens. in size. The The darkfragrant green flowers, foliage is cleanborn and in the long branching panicles, bloomis dense from and June full. toMaturing October atand a slightly attract pollinatorssmaller size by than the dozens.Delta Blues™. -

The Promise of Whiteness: Fifty Shades of Grey As White Racial Archive

Issue 8 January 2016 www.intensitiescultmedia.com The Promise of Whiteness: Fifty Shades of Grey as White Racial Archive Moon Charania Spelman College Abstract This paper looks closely at how whiteness—a key demonstrative site of power in Sam Taylor-Johnson’s egregious Fifty Shades of Grey (2015)—scripts a repertoire of behaviours on sexual, gender, racial, and class lines. Positioning Fifty Shades of Grey in the post 9/11 globalised media machine, I argue that this interna- tionally bestselling erotic phenomenon is haunted by the master narrative of white racism and heterosexual compulsion, where both are reconstituted as desirable in growing social climate of gay cosmopolitanism and anti-racist awareness. Wrought through a lexicon white superiority, Fifty Shades offers us a way of thinking about how dominant fe/male subject(s) employ whiteness as a crucial practice of producing social subordina- tion, and how a close reading of this film underscores the private and public pleasures of white subjectivity, and the inherent stability of white affluent subjectivity, despite its excesses—a position disallowed to queer and colored subjects. Analyzing various narrative moments in the film, I show how Christian Grey, despite his eroticization of violence, is nonetheless secured by distinctive individuality most closely associated with white bodies and the privileges of the white body politic. Grey’s irreducible and extradiagetic white pres- ence demand further thinking about how Fifty Shades is fundamentally about the pleasures (and promises) of whiteness. I argue that the ultimate duplicity of Fifty Shades of Grey is that it seduces viewers through a promise of explicit sex and wealth, even though the film’s true offering is much more simple: the promise of whiteness. -

Choose Paint Colors and Schemes

Choose Paint Colors and Schemes When you’re decorating your home, choosing the right paint colors is the most important decision you’ll make. As fun as choosing colors can be, this part of the planning can be overwhelming. Thousands of combinations are possible, but by having a basic understanding of color you can create a scheme you love. Basic Color Terms The Color Wheel The color wheel identifies color families and how they relate to each other. Primary Colors All colors, with the exception of white, come from primary colors.. Blue, yellow and red are the primary colors; combinations of these three colors produce secondary colors. Secondary Colors Mix equal amounts of two primary colors to create secondary colors. The results are violet (red and blue), green (blue and yellow) and orange (red and yellow). Tertiary Colors Mix one primary color with larger amounts of another primary color to create tertiary colors. For example, mix one part blue with two parts red to red-violet. Other Color Terms • The hue of a color is the basic color. For example, blue is the hue in light blue and dark blue. • Tone is the result of adding white and black (gray) to a color. Tone makes colors more pleasing to look at instead of pure pigment. • The value of a color describes the amount of white or black in the color. The value ranges from light to dark on a gray scale. • The saturation of a color refers to its strength or weakness in different light. Think about it in terms of bright or dull. -

4 Colour Words in English and Italian

Connotative meaning in English and Italian Colour-Word Metaphors Gill Philip, Bologna ([email protected]) Abstract Colour words are loaded with attributive, connotative meanings, many of which are realised in conventional linguistic expressions such as to feel blue, to be in the pink, and to see red. The use of such phrases on an everyday basis reinforces the currency of the connotative meanings which they assume in particular cultural and linguistic settings, and the phrases themselves are often cited as evidence of the existence of colours’ connotative meanings. But how do the colour words in conventional linguistic expressions relate to the multitude of symbolic meanings that colours (in general) are said to represent? Based on data extracted from general reference corpora as well as traditional reference works, this article examines the use of colour-word metaphors in English and Italian. It pays particular attention to the ways in which colour words take on connotative meanings, how the meanings are fixed linguistically, and similarities and differences across the two languages under examination. Farbbezeichnungen enthalten viele attributive und konnotative Bedeutungen, wobei viele von ihnen in umgangssprachlichen Ausdrücken vorkommen, wie z.B. to feel blue, to be in the pink und to see red. Die Verwendung derartiger Ausdrücke im alltäglichen Umgang trägt zur weiteren Verbreitung der konnotativen Bedeutungen innerhalb eines bestimmten kulturellen und sprachlichen Umfeldes bei, und die Ausdrücke selber werden oft als Beweis für den offensichtlichen konnotativen Aspekt der Farbbegriffe angeführt. In welchem Verhältnis stehen aber die konventionellen Ausdrücke zur großen Anzahl symbolischer Bedeutungen, die doch Farben (im Allgemeinen) darstellen sollen? Ausgehend von Resultaten allgemeiner reference corpora wie auch herkömmlicher Studien wird hier der Umgang mit Farbbezeichnungsmetaphern (idiomatische Ausdrücke) im Englischen und Italienischen untersucht. -

RGB to Color Name Reference

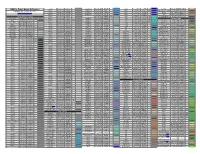

RGB to Color Name Reference grey54 138;138;138 8A8A8A DodgerBlue1 30;144;255 1E90FF blue1 0;0;255 0000FF 00f New Tan 235;199;158 EBC79E Copyright © 1996-2008 by Kevin J. Walsh grey55 140;140;140 8C8C8C DodgerBlue2 28;134;238 1C86EE blue2 0;0;238 0000EE 00e Semi-Sweet Chocolate 107;66;38 6B4226 http://web.njit.edu/~walsh grey56 143;143;143 8F8F8F DodgerBlue3 24;116;205 1874CD blue3 0;0;205 0000CD Sienna 142;107;35 8E6B23 grey57 145;145;145 919191 DodgerBlue4 16;78;139 104E8B blue4 0;0;139 00008B Tan 219;147;112 DB9370 Shades of Black and Grey grey58 148;148;148 949494 170;187;204 AABBCC abc aqua 0;255;255 00FFFF 0ff Very Dark Brown 92;64;51 5C4033 Color Name RGB Dec RGB Hex CSS Swatch grey59 150;150;150 969696 LightBlue 173;216;230 ADD8E6 cyan 0;255;255 00FFFF 0ff Shades of Green Grey 84;84;84 545454 grey60 153;153;153 999999 999 LightBlue1 191;239;255 BFEFFF cyan1 0;255;255 00FFFF 0ff Dark Green 47;79;47 2F4F2F Grey, Silver 192;192;192 C0C0C0 grey61 156;156;156 9C9C9C LightBlue2 178;223;238 B2DFEE cyan2 0;238;238 00EEEE 0ee DarkGreen 0;100;0 006400 grey 190;190;190 BEBEBE grey62 158;158;158 9E9E9E LightBlue3 154;192;205 9AC0CD cyan3 0;205;205 00CDCD dark green copper 74;118;110 4A766E LightGray 211;211;211 D3D3D3 grey63 161;161;161 A1A1A1 LightBlue4 104;131;139 68838B cyan4 0;139;139 008B8B DarkKhaki 189;183;107 BDB76B LightSlateGrey 119;136;153 778899 789 grey64 163;163;163 A3A3A3 LightCyan 224;255;255 E0FFFF navy 0;0;128 000080 DarkOliveGreen 85;107;47 556B2F SlateGray 112;128;144 708090 grey65 166;166;166 A6A6A6 LightCyan1 224;255;255 -

Page 1 of 100

Page 1 of 100 AGENDA HISTORIC PRESERVATION / DESIGN REVIEW COMMISSION Wednesday, October 7, 2015 – 4:30 PM City Conference Room – County-City Building 1515 Strongs Avenue – Stevens Point, WI 54481 (A Quorum of the City Council May Attend This Meeting) Discussion and possible action on the following: 1. Request from the City of Stevens Point for project review and release of façade improvement grant funds for Scott Gulan, representing Guu Inc. at 1140 Main Street (Parcel ID 2408-32-2029-31). 2. Request from the City of Stevens Point for a design review of a Cultural Commons (sister/partner cities) park at Pfiffner Pioneer Park, 1200 Crosby Avenue (Parcel ID 2408-32-2008-05). 3. Regulation of paint color within Historic Districts and the Downtown Design Review District. 4. Adjourn. Page 2 of 100 City of Stevens Point – Department of Community Development To: ,ŝƐƚŽƌŝĐWƌĞƐĞƌǀĂƚŝŽŶͬĞƐŝŐŶZĞǀŝĞǁŽŵŵŝƐƐŝŽŶ &ƌŽŵ͗ WůĂŶ^ƚĂĨĨ CC: ĂƚĞ͗ ϭϬͬϳͬϮϬϭϱ ZĞ͗ 1. ZĞƋƵĞƐƚĨƌŽŵ^ĐŽƚƚ'ƵůĂŶ͕ƌĞƉƌĞƐĞŶƚŝŶŐ'ƵƵ/ŶĐ͘ĨŽƌƉƌŽũĞĐƚƌĞǀŝĞǁĂŶĚƌĞůĞĂƐĞ ŽĨĨĂĕĂĚĞŝŵƉƌŽǀĞŵĞŶƚŐƌĂŶƚĨƵŶĚƐĂƚ1140 Main Street (Parcel ID 2408-32- 2029-31). ĞůŽǁŝƐĂƌĞǀŝĞǁĂŶĚƐƵŵŵĂƌLJŽĨƚŚĞ &ĂĕĂĚĞ/ŵƉƌŽǀĞŵĞŶƚ'ƌĂŶƚWƌŽŐƌĂŵĂǁĂƌĚreimbursement for Scotƚ'ƵůĂŶ͕ƌĞƉƌĞƐĞŶƚŝŶŐ'ƵƵ/ŶĐ͘ĂƚϭϭϰϬDĂŝŶ^ƚƌĞĞƚ. AůůŽĨƚŚĞĂƉƉƌŽǀĞĚƉƌŽũĞĐƚĂĐƚŝǀŝƚŝĞƐĂƐǁĞůůĂƐ͕ ĐŽŶĚŝƚŝŽŶƐŽĨĂƉƉƌŽǀĂůŚĂǀĞďĞĞŶŵĞƚ;ƐĞĞbelow) ƌĞŐĂƌĚŝŶŐthe ĨĂĕĂĚĞŝŵƉƌŽǀĞŵĞŶƚƉƌŽũĞĐƚĂƚϭϭϰϬ DĂŝŶ^ƚƌĞĞƚ. Façade Improvement Grant Program Activities x /ŶƐƚĂůůďůĂĐŬŵĞƚĂůĨĞŶĐŝŶŐĂŶĚĐŽƌƌƵŐĂƚĞĚŵĞƚĂůͬǁŽŽĚĞŶĨƌĂŵĞ͕ĞŶĐůŽƐŝŶŐĂŶĚƐƵƌƌŽƵŶĚŝŶŐƚŚĞ ƉĂƚŝŽĂƌĞĂ͘ x WĂŝŶƚƚŚĞŶŽƌƚŚĨĂĕĂĚĞ x /ŶƐƚĂůůďůĂĐŬŵĞƚĂůƌŽŽĨͬŽǀĞƌŚĂŶŐĐŽǀĞƌŝŶŐĂƉŽƌƚŝŽŶŽĨƚŚĞƉĂƚŝŽĂƌĞĂ͘ -

Brehob Nursery's 2020 New Perennials

Brehob Nursery’s 2020 New Perennials ‘Spring Beauty’ Anemone • Height: 18 inches • Spread: 12-15 inches • Color: magenta • Sun: part sun • Bloom Time: late spring, early summer ‘Lavender Bubbles’ Allium • Height: 12-14 inches • Spread: 20-22 inches • Color: shades of purple • Sun: part shade- full sun • Bloom Time: late summer, early fall • Height: 20-28 inches • Spread: 24 inches ‘Black Pearls’ • Astilbe Color: purple • Sun: part shade to full sun • Bloom Time: summer ‘Heavy Metal’ Astilbe • Height: 24-30 inches • Spread: 24 inches • Color: cherry red • Sun: partial shade to shade • Bloom Time: summer ‘Little Vision in Pink’ Astilbe • Height: 24-32 inches • Spread: 12-24 inches • Color: pink • Sun: full shade to partial sun • Bloom Time: early to mid-summer ‘Lowlands Ruby Red’ Astilbe • Height: 20-24 inches • Spread: 24 inches • Color: red • Sun: part shade to full sun • Bloom Time: mid-summer ‘Pinball Wizard’ Dianthus Height: 9-12 inches Spread: 9-12 inches Color: shades of pink Sun: partial to full sun Bloom Time: mid- spring Butterfly ‘Cleopatra’ Coneflower • Height: 16-18 inches • Spread: 12-16 inches • Color: golden yellow • Sun: part sun to sun • Bloom Time: mid-late summer ‘Kismet White’ Coneflower • Height: 15-18 inches • Spread: 18 inches • Color: white • Sun: full sun • Bloom Time: summer ‘Fine Feathered Parrot’ Coneflower • Height: 16-18 inches • Spread: 12-16 inches • Color: bi-color red and yellow blooms • Sun: part sun to sun • Bloom Time: mid-late summer ‘Mellow Yellows’ Coneflower • Height: 24-30 inches • Spread: 12-24 -

Cottage Garden – Plant List

What Really Goes on in a Cottage Garden Lindsay A. Hendricks – Assistant Director of Horticulture Plant List Heirlooms & Reseeding Annuals Acidanthera murielae – peacock orchid – zone 6, sun, 24-36” tall, grass-like foliage, fragrant white flowers on slender stems, plant bulbs in spring for summer bloom, bulbs can be dug and overwintered Alcea rosea – common hollyhock – biennial, 5-7’ high, sun, tall stems bearing mostly single blossoms of deep rose, pink, salmon-pink, and white; may self-sow Allium cvs. – ornamental onion – zone 5, sun, flowers of various heights and various shades of white, purple, pink; flowers late May through June. Cultivars: Ambassador Amaranthus caudatus – love lies bleeding – annual, 3-4’ high, 2’ wide, sun, long drooping clusters of reddish pink flowers, may self-sow. Cultivars: Viridis Amaranthus cruentus – tall amaranth – annual, 6-8’ high, 2’ wide, sun, dark purple foliage and flower spikes, long blooming, fall interest with blooms and foliage, self-sows Anemone hupehensis – windflower – zone 4, 2-4’ high, 2-3’ wide, full sun to part shade, flowers silvery pink with white shading, blooms August to October Angelica gigas – Korean angelica – biennial, 4-6’ high, full sun to part shade, tall purple stems with deep violet-purple umbels, attracts amazing array of pollinators, self-sows Aster laevis – smooth aster – zone 4, 2-4’ high, 1-2’ wide, sun; small violet blue to flowers; stems unbranched with smooth, bluish green foliage; fall interest, attracts butterflies. Raydon’s Favorite Canna – canna lily – zone 8, up to 7’ high, sun; flowers shades of red, pink, orange, yellow; foliage green to bronze, some with striping; performs best in warmer weather when given adequate water, tubers can be dug and overwintered. -

Xeriscaping in the High Desert and Pictorial Plant Guide for Central & Eastern Oregon Mayors of the Central Oregon Cities Organization

An Introduction to Xeriscaping in the High Desert And Pictorial Plant Guide for Central & Eastern Oregon Mayors of the Central Oregon Cities Organization Welcome We live in one of the most beautiful regions in the West. It is also one of the fastest growing areas in the country. With natural precipitation less than 5 inches during the April through October growing season, consideration of water use for our landscapes is very important. The water resources of our region are shared by all, and as such we each have a responsibility to use it wisely. The typical resident uses over 50% of the water they use annually, outside for landscaping. Landscapes add value, beauty and livability to our homes and keeping them WaterWise is a critical part of being a good steward in this incredible region. We all need to become WaterWise partners in order to protect our water resources for our grandkids. This Xeriscape™ guide, put together by our regional horticulture, irrigation and water conservation experts, is one tool to assist you in effective water management. By adopting the seven steps of xeriscaping, from design – to ongoing maintenance, not only can you plan a gorgeous landscape for your home or business, but you can do it in a low impact, sustainable way. Less water, less maintenance, less chemicals, less run- off, less energy use, less worry. These are just some of the benefits that can allow you more time to enjoy the many amenities of this region. Whether landscaping a new home or business, or revisiting your existing landscape, please consider this Xeriscape guide as a place to begin your effort to turn your landscape into a WaterWise work of beauty. -

MVHA Historic Color Guidelines

MONTE VISTA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION GUIDELINESGUIDELINES FORFOR COLORSCOLORS ANDAND TEXTURETEXTURE PREPARED BY: THE UTSA COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE TABLE OF CONTENTS Why it is important to choose appropriate paint colors for my home? 1.01 How do I use this guide? 1.02 What do I need to know before I start? 1.03 What style is my house? 1.05 What colors are appropriate for the style of my home? 1.12 Victorian Palette Colonial Revival Palette Neoclassical Palette Tudor Style Palette Italian Renaissance Revival Palette Spanish Inspired Palette Prairie & Craftsman Palette What kind of roof is appropriate for the style of my home? 1.22 Glossary 1.24 Resources for homeowners 1.27 Bibliography 1.29 Image Sources 1.31 MONTE VISTA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION GUIDELINES FOR COLORS AND TEXTURE WHY IT IS IMPORTANT TO CHOOSE APPROPRIATE PAINT COLORS FOR MY HOME? Color is an important defining characteristic of historical homes. Like a home’s deco- rative architectural details, color reflects both the style of a house and the time when it was built. Choosing historically appropriate exterior colors and using them in historically appropriate ways can highlight the architectural character of a home, strengthen its historical integrity and enhance the continuity of an his- toric district. Less appropriate choices can obscure the unique architectural features of a home, weaken its historical value and disrupt the historical context of a neigh- borhood. Recognizing the importance of color to the value of historical homes, several national companies, such as Sherwin-Williams, Benjamin Moore, California Paints and Valspar, have worked with preservation groups like the National Trust for Historic Preserva- tion and Historic New England to produce a wide array of historically accurate colors for consumers.