American Winemaking Comes of Age | 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calder and Sound

Gryphon Rue Rower-Upjohn Calderand Sound Herbert Matter, Alexander Calder, Tentacles (cf. Works section, fig. 50), 1947 “Noise is another whole dimension.” Alexander Calder 1 A mobile carves its habitat. Alternately seductive, stealthy, ostentatious, it dilates and retracts, eternally redefining space. A noise-mobile produces harmonic wakes – metallic collisions punctuating visual rhythms. 2 For Alexander Calder, silence is not merely the absence of sound – silence gen- erates anticipation, a bedrock feature of musical experience. The cessation of sound suggests the outline of a melody. 3 A new narrative of Calder’s relationship to sound is essential to a rigorous portrayal and a greater comprehension of his genius. In the scope of Calder’s immense œuvre (thousands of sculptures, more than 22,000 documented works in all media), I have identified nearly four dozen intentionally sound-producing mobiles. 4 Calder’s first employment of sound can be traced to the late 1920s with Cirque Calder (1926–31), an event rife with extemporised noises, bells, harmonicas and cymbals. 5 His incorporation of gongs into his sculpture followed, beginning in the early 1930s and continuing through the mid-1970s. Nowadays preservation and monetary value mandate that exhibitions of Calder’s work be in static, controlled environments. Without a histor- ical imagination, it is easy to disregard the sound component as a mere appendage to the striking visual mien of mobiles. As an additional obstacle, our contemporary consciousness is clogged with bric-a-brac associations, such as wind chimes and baby crib bibelots. As if sequestered from this trail of mainstream bastardi- sations, the element of sound in certain works remains ulterior. -

Official Results 2012 OHIO WINE COMPETITION

2012 Official Results 2012 OHIO WINE COMPETITION Date: May 7-9, 2012 Location: Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, Wooster, Ohio Competition Coordinator: Todd Steiner, OARDC, Wooster, OH Asst. Coordinator: Patrick Pierquet, OARDC, Wooster, OH Judges: • Ken Bement, Owner, Whet Your Whistle Wine Store, Madison, OH • Jill Blume, Enology Research Associate and Executive Director of The Indy International Wine Competition, Department of Food Science, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN • Ken Bogucki, Proprietor and Executive Chef, The Wooster Inn, Wooster, OH • Kim Doty, Owner/Winemaker, French Lick Winery, French Lick, IN • Mark Fisher, Retail and Restaurants Reporter, Cox Media Group Ohio, Dayton OH • Jim Mihiloew, Certified Wine Educator and AWS Judge, Middleburg Heights, OH • Amy Payette, Director of Marketing, Grey Ghost Vineyards, Amissville, VA • Thomas Payette, Wine Judge, Winemaking Consultant, Rapidan, VA • Dr. Andy Reynolds, Professor of Viticulture and past Interim Director, Cool Climate Oenology and Viticulture Institute, Brock University, St. Catherine’s, Ontario, Canada • Chris Stamp, Owner/Winemaker, Lakewood Wine Cellars, Watkins Glenn, NY Entries: 268 Awards: CG (Concordance Gold): 20 Gold: 26 Silver: 73 Bronze: 71 2012 Ohio Wine Competition Best of Show Awards Overall Best of Show: Ravens Glenn Winery, Cabernet Sauvignon, 2007, American Best of Show White Wine: Ferrante Winery, Riesling, 2011, American Best of Show Red Wine: Ravens Glenn Winery, Rosso Grande, 2009, American Best of Show Blush/Rose: Henke -

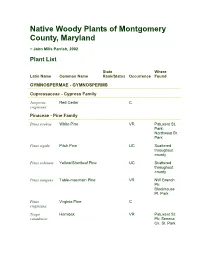

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland ~ John Mills Parrish, 2002 Plant List State Where Latin Name Common Name Rank/Status Occurrence Found GYMNOSPERMAE - GYMNOSPERMS Cupressaceae - Cypress Family Juniperus Red Cedar C virginiana Pinaceae - Pine Family Pinus strobus White Pine VR Patuxent St. Park; Northwest Br. Park Pinus rigida Pitch Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus echinata Yellow/Shortleaf Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus pungens Table-mountain Pine VR NW Branch Pk; Blockhouse Pt. Park Pinus Virginia Pine C virginiana Tsuga Hemlock VR Patuxent St. canadensis Pk; Seneca Ck. St. Park ANGIOSPERMAE - MONOCOTS Smilacaceae - Catbrier Family Smilax glauca Glaucous Greenbrier C Smilax hispida Bristly Greenbrier UC/R Potomac (syn. S. River & Rock tamnoides) Ck. floodplain Smilax Common Greenbrier C rotundifolia ANGIOSPERMAE - DICOTS Salicaceae - Willow Family Salix nigra Black Willow C Salix Carolina Willow S3 R Potomac caroliniana River floodplain Salix interior Sandbar Willow S1/E VR/X? Plummer's & (syn. S. exigua) High Is. (1902) (S.I.) Salix humilis Prairie Willow R Travilah Serpentine Barrens Salix sericea Silky Willow UC Little Bennett Pk.; NW Br. Pk. (Layhill) Populus Big-tooth Aspen UC Scattered grandidentata across county - (uplands) Populus Cottonwood FC deltoides Myricaceae - Bayberry Family Myrica cerifera Southern Bayberry VR Little Paint Branch n. of Fairland Park Comptonia Sweet Fern VR/X? Lewisdale, peregrina (pers. com. C. Bergmann) Juglandaceae - Walnut Family Juglans cinerea Butternut S2S3 R -

TGE) & the JOB Board

1 2017 The Grape Exchange (TGE) & The JOB Board As of 7/1/17, Christy Ecktein will be handling OGEN, TGE & TJB. Please contact Christy at [email protected] This service is provided by the OSU viticulture program. The purpose of this site is to assist grape growers and wineries in selling and/or buying grapes, wine, juice or equipment and post JOBS Wanted or JOBS for Hire. The listing will be posted to the “Buckeye Appellation” website (https://ohiograpeweb.cfaes.ohio-state.edu/ ) and updates will be sent to all OGEN subscribers via email. Ads will be deleted after 4 months. If you would like items to continue or placed back on the exchange, please let me know. To post new or make changes to current ads, please send an e-mail to Christy Eckstein ([email protected]) with the contact and item description information below. Weekly updates of listings will be e-mailed to OGEN subscribers or as needed throughout the season. Suggestions to improve the Grape Exchange are also welcome. The format of the information to include is as follows: Items (grapes, wine, equipment, etc) Wanted/Needed or Selling: Name: Vineyard/Winery: Phone Number: E-mail Address: Note: Please send me a note to delete any Ads that you no longer need or want listed. There are currently four jobs listed on The JOB Board. Updates to TGE are listed as most current to oldest. *Please scroll down to Ads, pictures & contact information 2 The Grape Exchange September 21, 2017 (32) For Sale: Niagra and Concord grapes. -

Growing Grapes in Missouri

MS-29 June 2003 GrowingGrowing GrapesGrapes inin MissouriMissouri State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University-Mountain Grove Growing Grapes in Missouri Editors: Patrick Byers, et al. State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University Department of Fruit Science 9740 Red Spring Road Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711-2999 http://mtngrv.missouristate.edu/ The Authors John D. Avery Patrick L. Byers Susanne F. Howard Martin L. Kaps Laszlo G. Kovacs James F. Moore, Jr. Marilyn B. Odneal Wenping Qiu José L. Saenz Suzanne R. Teghtmeyer Howard G. Townsend Daniel E. Waldstein Manuscript Preparation and Layout Pamela A. Mayer The authors thank Sonny McMurtrey and Katie Gill, Missouri grape growers, for their critical reading of the manuscript. Cover photograph cv. Norton by Patrick Byers. The viticulture advisory program at the Missouri State University, Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center offers a wide range of services to Missouri grape growers. For further informa- tion or to arrange a consultation, contact the Viticulture Advisor at the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center, 9740 Red Spring Road, Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711- 2999; telephone 417.547.7508; or email the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center at [email protected]. Information is also available at the website http://www.mvec-usa.org Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction.................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2 Considerations in Planning a Vineyard ........................................................ -

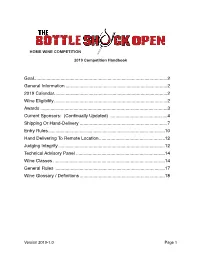

Unique Wines - 840 Anything Not Covered in Above Classes

HOME WINE COMPETITION 2019 Competition Handbook Goal......................................................................................................... 2 General Information................................................................................ 2 2019 Calendar......................................................................................... 2 Wine Eligibility......................................................................................... 2 Awards.................................................................................................... 3 Current Sponsors: (Continually Updated) .............................................4 Shipping Or Hand-Delivery..................................................................... 7 Entry Rules............................................................................................ 10 Hand Delivering To Remote Location.................................................... 12 Judging Integrity.................................................................................... 12 Technical Advisory Panel...................................................................... 14 Wine Classes........................................................................................ 14 General Rules ......................................................................................17 Wine Glossary / Definitions................................................................... 18 Version 2019-1.0 Page !1 GOAL Our goal is to initiate and develop a stable amateur wine -

Training Systems for Cold Climate Hybrid Grapes in Wisconsin

A4157 Training systems for cold climate hybrid grapes in Wisconsin A. Atucha and M. Wimmer Cold climate hybrid grape cultivars (e.g., ‘Marquette’, ‘Frontenac’, ‘La Crescent’, ‘Brianna’, etc.) differ from European grape (Vitis vinifera) cultivars in several respects and require separate consideration with regard to the most appropriate training system. This publication focuses on aspects to consider when choosing a training system for cold climate hybrid grapes. Introduction Choosing a training system The training of grapevines refers to the physical action of The choice of an adequate training system will be influenced by manipulating a vine into a particular size, shape, and orientation. the following factors. The main objectives of training grapevines are to: 1. Maximize the interception of light by leaves and clusters, Cultivar growth habit Cold climate hybrids have a broad range of growth habits from leading to higher yield, improved fruit quality, and better procumbent (or downwards) to upright, and the choice of training disease control; system should adapt to the growth characteristic of the cultivar. 2. Facilitate pruning, canopy management, harvesting, and Cold climate hybrid cultivars with procumbent growth adapt well mechanization of the vineyard; to training systems that have downward shoot orientation such 3. Arrange trunks, cordon, and canes to avoid shading between as high wire cordon (HWC) (figure 1) or Geneva double curtain vines; and (GDC) (figure 2). 4. Promote light exposure in the renewal zone (i.e., spurs or heads) to maintain vine productivity. FIGURE 1. High wire cordon (HWC) is a downward FIGURE 2. Geneva double curtain (GDC) trained with two spur-pruned training system. -

2007 Ohio Wine Competition

Official Results 2007 OHIO WINE COMPETITION Date: May 14-16, 2007 Location: Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, Wooster, Ohio Competition Coordinator: Todd Steiner, OARDC, Wooster, OH Asst. Comp. Coordinators: Taehyun Ji and Dave Scurlock, OARDC, Wooster, OH Judges Chairman: Todd Steiner, Brian Sugerman OARDC, Wooster, OH Judges: Ken Bement, Owner, Whet Your Whistle Wine Store, Madison, OH Peter Bell, Winemaker, Enologist, Fox Run Vineyards, Penn Yenn, NY Amy Butler, Tasting Room Manager, Butler Winery, Bloomington, IN Nancie Corum, Asst. Winemaker, St. Julian Wine Company, Paw Paw, MI Jim Mihaloew, Certified Wine Educator and AWS Judge, Strongsville, OH Johannes Reinhardt, Winemaker, Anthony Road Winery, Penn Yan, NY Sue-Ann Staff, Head of Winemaking Operations, Pillitteri Estates Winery, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Canada Entries: 265 Awards: Gold: 25 Silver: 69 Bronze: 79 2007 Ohio Wine Competition Summary of Awards by Medal WINERY WINE NAME VINTAGE APPELLATION MEDAL Breitenbach Wine Cellars Apricot NV American G Breitenbach Wine Cellars ThreeBerry Blend NV American G Breitenbach Wine Cellars Blueberry NV American G Debonne Vineyards Riesling 2006 Grand River Valley G Debonne Vineyards Chambourcin 2005 Grand River Valley G Debonne Vineyards Vidal Blanc 2006 Grand River Valley G Ferrante Winery & Ristorante Vidal Blanc 2006 Grand River Valley G Ferrante Winery & Ristorante Pinot Grigio Signature Series 2006 Grand River Valley G Ferrante Winery & Ristorante Riesling Signature Series 2006 Grand River Valley G Firelands Winery Gewurztraminer 2006 Isle St. George G Grand River Cellars Vidal Blanc Ice Wine 2005 Grand River Valley G Hermes Vineyards Semillon 2006 Lake Erie G Klingshirn Winery, Inc. Niagara NV Lake Erie G Klingshirn Winery, Inc. -

Defies Convention Palacios, Chief Winemaker of Bodegas Faustino in Rioja Alavesa, Spain

OCTOBER 2018 • $6.95 Rioja’sNEWFOUND EDGE AFTER MORE THAN 150 YEARS OF PRODUCTION, FAUSTINO Rafael Martínez Defies Convention Palacios, Chief Winemaker of Bodegas Faustino in Rioja Alavesa, Spain. TP1018_001-31_KNV5.indd 1 RIOJA’S 10/1/18 6:29 PM NEWFOUND tastingpanel TP1018_001-31_KNV5.indd 2 10/1/18 6:29 PM tastingTHE panel tastingpanel MAGAZINE October 2018 • Vol. 76 No. 9 editor in chief publisher / editorial director vp / associate publisher managing editor Anthony Dias Blue Meridith May Rachel Burkons Jesse Hom-Dawson [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 818-990-0350 CONTRIBUTORS senior design director Michael Viggiano [email protected] Erica Bartel, Kim Beto, Brandon Boghosian, Randy Caparoso, Madelyn vp, sales and marketing Gagnon, Albert Letizia, Michelle Metter, Jennifer Olson, Alexander [email protected] Rubin, Benjamin Rusnak, Grace Stufkosky, James Tran, Paul Van Hoy Bill Brandel senior wine editor Published eleven times a year Jessie Birschbach [email protected] ISSN# 2153-0122 USPS 476-430 senior editor Chairman/CEO: Anthony Dias Blue Kate Newton [email protected] President/COO: Meridith May special projects editor Subscription Rate: $36 One Year; $60 Two Years; Single Copy: $6.95 David Gadd [email protected] For all subscriptions, email: [email protected] Periodicals Postage Paid at Van Nuys and at additional mailing offices east coast editor David Ransom Devoted to the interests and welfare of United States restaurant and retail store licensees, wholesalers, rocky mountain editor importers and manufacturers in the beverage industry. Ruth Tobias POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: The Tasting Panel Magazine features editor 6345 Balboa Blvd; Ste 111, Encino, California 91316, Michelle Ball 818-990-0350 editor-at-large Cliff Rames STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP wine country editor The Material in each issue of The Tasting Panel Magazine is protected Chris Sawyer by U.S. -

An Overview of the Ohio Quality Wine Program (OQW)

An Overview Of The Ohio Quality Wine Program (OQW) Todd Steiner Horticulture & Crop Science The Ohio State University/OARDC Wooster, OH 44691 THANK YOU! 2014 Ohio Grape and Wine Conference Conference Organizing Committee – Specifically, Christy Eckstein and Dave Scurlock for their significant involvement in organization and preparation of the conference The Crowne Plaza Host Hotel – Crystal Culp and wonderful staff OQW History Initial groundwork began in 1999 and 2000 Key members – Ohio State University – OWPA – Several key wine industry personnel Worked together in developing a quality wine assurance program draft OQW History 1999/2000 OQW Personnel Involvement OSU/OARDC Dr. Dave Ferree OSU/OARDC Dr. Jim Gallander Dr. Roland Riesen OSU/OARDC Todd Steiner OSU/OARDC Dave Scurlock OSU/OARDC ODA Bruce Benedict OWPA Donniella Winchell Ohio Wine Industry Nick Ferrante Ohio Wine Industry Jeff Nelson Ohio Wine Industry Claudio Salvadore OQW History After developing a fairly thorough rough draft, nothing had been accomplished further until 2004 A joint collaboration of ODA/(OGIC) and OSU/OARDC placed a considerable effort in updating, changing and kick starting the new OQW program Fred Daily: Director of Agriculture, OGIC Michelle Widner: Executive Director, OGIC OQW History An OGIC subcommittee was formed to follow through and initiate this program The subcommittee: – OGIC board members – OSU/OARDC representatives We examined other successful states and countries with quality programs in place OQW History Program information was gathered from: – Steve Burns, Washington Wine Quality Alliance (WWQA) – Dr. Gary Pavlis, New Jersey Wine Quality Alliance – Len Pennachetti, Vintners Quality Alliance Ontario (VQA) Recent and Current Contributing OQW Team Members (2004-2012) ODA, OGIC Director, Robert Boggs (past), David Daniels (current) ODA, OGIC Deputy Dir. -

La Misíon De La Sénora Bárbara, Vírgen Y Martír

Mission Santa Michael Sánchez received a Bachelor of Science in Landscape Barbara Architecture from California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo in 1996. He worked as a landscape architect for | ten years before deciding to go back to school for a master’s Visually degree in landscape architecture. He plans to continue working in private practice as well as teach. La Misíon de la Sénora Bárbara, Vírgen y Martír Explored Mission Santa Barbara | Visually Explored Visual imagery is very powerful to how we learn, remember and communicate. Images remain in our Michael A. Sánchez, 2010 psyche long after words have fallen silent and return as helpful references at a later date. This project is Submitted to the UNIVERSITY OF OREGON, Department of Landscape Architecture, College of Architecture and the Allied Arts not a typical historical analysis of the landscape of Mission Santa Barbara, nor a detailed historic rendering of the beautiful architecture and surrounding landscape. Nor is this merely a literary compilation. This project is a unique perspective between all of the professionals that tell stories of the missions – architects, landscape architects, planners, artists, historians, archeologists, anthropologists, Padres, tourists, etc. – and is woven into a product rich in illustrations and backed by interesting facts and sources. This project illustrates elements of the mission that most people might not see from a typical tourist viewpoint. This visual essay communicates the rich history of this influential place in a way that more fully demonstrates the fascinating elements of this mission’s systems and strives to lead the reader to a greater appreciation of this place that is part building, part garden, part lore. -

Development of Flavonoid Compounds in Norton and Cabernet Sauvignon Grape Skins

Development of Flavonoid Compounds in Norton and Cabernet Sauvignon Grape Skins during Maturation A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science By NICOLE ELIZABETH DOERR Dr. Reid Smeda, Thesis Supervisor May 2014 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the Thesis entitled DEVELOPMENT OF FLAVONOID COMPOUNDS IN NORTON AND CABERNET SAUVIGNON GRAPE SKINS DURING MATURATION Presented by Nicole Elizabeth Doerr A candidate for the degree of Master of Science And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Reid Smeda Professor Misha Kwasniewski Assistant Professor Wenping Qiu Adjunct Professor ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisors, Dr. Reid Smeda and Dr. Misha Kwasniewski, for their willingness to take me on as a graduate student. Their insight and knowledge was extremely helpful these past couple of years in furthering my understanding of grape and wine. I would also like to thank my other committee member Dr. Wenping Qiu for his valuable insight. Additionally, I would like to thank all the past and present faculty, staff, and students of the Grape and Wine Institute. In particular, Dr. Anthony Peccoux and Dr. Ingolf Gruen, thank you for your guidance and encouragement. I would also like to thank Ashley Kabler for her help on my research projects. Thank you for your hard work, and friendship; without it I might still be picking and peeling berries. To my fellow graduate students: John, Ashley, Spencer, Tye, Andres, Hallie, Michael, Erin, and Jackie, thank you for your help with statistics, classes, papers, abstracts and presentations.