Bank for Your Buck: Increasing Savings in Tanzania Second-Year Policy Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issn 0856 – 8537 Directorate of Banking

ISSN 0856 – 8537 DIRECTORATE OF BANKING SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2017 21ST EDITION For any enquiries contact: Directorate of Banking Supervision Bank of Tanzania 2 Mirambo Street 11884 Dar Es Salaam TANZANIA Tel: +255 22 223 5482/3 Fax: +255 22 223 4194 Website: www.bot.go.tz TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................... Page LIST OF CHARTS ........................................................................................................................... iv ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................................................ v MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR ........................................................................................... vi FOREWORD BY THE DIRECTOR OF BANKING SUPERVISION .............................................. vii CHAPTER ONE .............................................................................................................................. 1 OVERVIEW OF THE BANKING SECTOR .................................................................................... 1 1.1 Banking Institutions ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Branch Network ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Agent Banking ........................................................................................................................ -

Basic Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile

The United Republic of Tanzania Basic Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance Dar es Salaam and Office of Chief Government Statistician Ministry of State, President ’s Office, State House and Good Governance Zanzibar April, 2014 UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA, ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARIES Basic Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile Foreword The 2012 Population and Housing Census (PHC) for the United Republic of Tanzania was carried out on the 26th August, 2012. This was the fifth Census after the Union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar in 1964. Other censuses were carried out in 1967, 1978, 1988 and 2002. The 2012 PHC, like previous censuses, will contribute to the improvement of quality of life of Tanzanians through the provision of current and reliable data for policy formulation, development planning and service delivery as well as for monitoring and evaluating national and international development frameworks. The 2012 PHC is unique as the collected information will be used in monitoring and evaluating the Development Vision 2025 for Tanzania Mainland and Zanzibar Development Vision 2020, Five Year Development Plan 2011/12–2015/16, National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP) commonly known as MKUKUTA and Zanzibar Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (ZSGRP) commonly known as MKUZA. The Census will also provide information for the evaluation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2015. The Poverty Monitoring Master Plan, which is the monitoring tool for NSGRP and ZSGRP, mapped out core indicators for poverty monitoring against the sequence of surveys, with the 2012 PHC being one of them. Several of these core indicators for poverty monitoring are measured directly from the 2012 PHC. -

The United Republic of Tanzania the Economic Survey

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA THE ECONOMIC SURVEY 2017 Produced by: Ministry of Finance and Planning DODOMA-TANZANIA July, 2018 Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................... xiii- xvii CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................. 1 THE DOMESTIC ECONOMY .................................................................... 1 GDP Growth ............................................................................................. 1 Price Trends .............................................................................................. 7 Capital Formation ................................................................................... 35 CHAPTER 2 ............................................................................................... 37 MONEY AND FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS ......................................... 37 Money Supply ......................................................................................... 37 The Trend of Credit to Central Government and Private Sector ............ 37 Banking Services .................................................................................... 38 Capital Markets and Securities Development ......................................... 37 Social Security Regulatory Authority (SSRA) ....................................... 39 National Social Security Fund (NSSF) ................................................... 40 GEPF Retirement Benefits Fund ........................................................... -

NMB Bank – Bridging the Unbanked

Savings at the Frontier (SatF) A Mastercard Foundation partnership with Oxford Policy Management Project Briefing: NMB Bank – Bridging the Unbanked Introduction Tanzania’s NMB Bank Plc (NMB) is receiving support of up to $1,000,000 from SatF to bring formal financial services to some of Tanzania’s most excluDeD communities. NMB has partnered with CARE International anD will use the funDing to Digitise anD scale up the Bank’s current efforts to reach savings groups in peri-urban and rural parts of Tanzania. The project’s aim is that, By 2020, NMB will be clearly on track to making group anD group memBer outreach sustainaBle By aDDing 100,000 active rural anD peri-urban customers to its user base. These customers should Be clearly iDentifiaBle as memBers of savings groups, thereBy contriButing to the Bank’s longer term goal of signing up 28,000 savings groups with up to 600,000 memBers actively using NMB accounts. What difference will SatF’s support make? SatF’s support is helping NMB to link its existing group proDuct (Pamoja) with ChapChap, an entry- level inDividual moBile Banking proDuct. This is enabling NMB to keep transaction charges low anD tailor its offer to the neeDs of rural, unBankeD customers – particularly women. The Bank will also Be testing the efficiency gains from integrating Pamoja (the group proDuct) anD CARE’s Chomoka smartphone application for savings groups (SGs). Chomoka enables groups to Digitise their recorDs anD track the savings anD creDit histories of groups anD their memBers. The funDing will also enaBle NMB to Develop anD test a tailoreD creDit proDuct suiteD to the emerging neeDs, revealeD preferences of group members as well as their willingness anD ability to meet financial commitments. -

Amended Memorandum And

AMENDED MEMORANDUM AND ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION OF THE TANZANIA INSTITUTE OF BANKERS INCORPORATED DAY OF 1993 AMENDED PER RESOLUTION DATED 28 SEPTEMBER 2016 Drawn By: A. H. M. Mtengeti Advocate P O Box 2939 DAR ES SALAAM THE COMPANIES ACT CAP 212 COMPANY LIMITED BY GUARANTEE AND NOT HAVING SHARE CAPITAL AMENDMENT TO THE MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION OF THE TANZANIA INSTITUTE OF BANKERS LIMITED INCORPRATION AND NATURE OF THE INSTITUTE 1. The name of the Company is “THE TANZANIA INSTITUTE OF BANKERS LIMITED” a non-profit company incorporated and existing under the laws of the United Republic of Tanzania. 2. The Registered Office of the Institute shall be situated at Dar es Salaam, in the United Republic of Tanzania. 3. The main object for which the Institute is established is to certify professionally qualified bankers in Tanzania. 4. In furtherance of the object set out in clause 3 above, the Institute shall have the following roles: i. To play a leading role as the professional body for persons engaged in the banking and financial services industry, to promote the highest standards of competence, practice and conduct among persons engaged in the banking and financial services industry, and to assist in the professional development of its Members, whether by means of examination, awards, certification or otherwise and ensure quality assurance. ii. To promote, encourage and advance knowledge and best practices in banking and financial services in all their aspects, whether conventional or Islamic, and any other products or activities as may, from time to time, be undertaken by the banks and financial institutions. -

2012 Population and Housing Census

The United Republic of Tanzania Basic Demographic and Socio- Economic Profile 2014 Key Findings 2012 Population and Housing Census Overview The United Republic of Tanzania carried out a Population and Housing Census (PHC) on 26th August, 2012. The 2012 PHC was the fifth Census after the Union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar in 1964. Other censuses were carried out in 1967, 1978, 1988 and 2002. The fundamental objective of the 2012 PHC was to provide information on the size, distribution, composition and other socio-economic characteristics of the population, as well as information on housing conditions. The 2012 PHC also used a Community Questionnaire to collect information on the availability of socio-economic services such as schools and hospitals. The information provided is useful for monitoring and evaluating the country’s development programmes. The 2012 Tanzania Basic Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile provide short descriptive analyses and related tables on main thematic areas covered in the 2012 PHC. Topics covered in the report include population size and growth, age and sex distributions; household composition, marital status, disability, citizenship, birth registration and diaspora. Other topics are fertility and mortality, survival of parents, literacy and education, economic activities, housing conditions, ownership of assets, household amenities, agriculture and livestock; and social security funds. This booklet gives a summary of the 2012 Basic Demographic and Socio-Economic Profiles of Tanzania (Volume IIIA), Tanzania Mainland (Volume IIIB), Tanzania Zanzibar (Volume IIIC) and a Detailed Statistical Tables for National Basic Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile (Volume IIID). In many cases, characteristics have been disaggregated by rural and urban areas. -

Invitation for Tenders

TANZANIA ELECTRIC SUPPLY COMPANY LTD Tender No. PA/001/2020-2021/HQ/G/185 For Supply of equipment and materials for construction of 400/220/132/132kV Chalinze substation Invitation for Tenders Date: 25/03/2021 1. The Government of the United Republic of Tanzania though Tanzania Electric Supply Company Limited (TANESCO) has funds for implementation of various strategic projects during the financial year 2020-2021. It is intended that part of the proceeds of the fund will be used to cover eligible payment under the contract for the Supply of equipment and materials for construction of 400/220/132/132kV Chalinze substation which is divided into the following scope: - - lot 1 for Supply of switchyard equipment - Lot 2 for Supply of Control, Protection and SCADA system equipment - Lot 3 for Supply of Steel Towers and Gantry structures 2. Each Lots has its own Tendering documents. Tenderer are allowed to quote for all Lots or Individual Lot. 3. The award will be made on Lot basis. 4. The Tanzania Electric Supply Company Limited (TANESCO) now invites tenders from eligible Manufacturers/Authorized dealers of Supply of equipment and materials for construction of 400/220/132/132kV Chalinze substation. 5. Tendering will be conducted through the International Competitive Tendering procedures specified in the Public Procurement Regulations, 2013 – Government Notice No. 446 as amended in 2016, and is open to all Tenderers as defined in the Regulations. 6. Interested eligible Tenderers may obtain further information from and inspect the Tendering document during office hours from 09:00 to 16:00 hours at the address given below; - The Secretary Tender Board, Tanzania Electric Supply Company Ltd, Street Address: Morogoro Road, Ubungo Area, Building/Plot No: Umeme Park Building, Floor/Room No: Ground Floor, Room No. -

NMB Bank Limited

NMB Bank Limited ICRA Nepal assigns Issuer Rating of [ICRANP-IR] BBB and [ICRANP] LBBB rating to subordinated Debentures of NMB Bank Limited Amount (NPR) Rating Action Issuer Rating NA [ICRANP-IR] BBB (Assigned) Subordinated Debentures 500 million [ICRANP] L BBB (Assigned) Programme ICRA Nepal has assigned rating of [ICRANP-IR] BBB (pronounced ICRA NP Issuer Rating triple B) to NMB Bank Limited (hereinafter referred to as NMB). Instruments with [ICRANP-IR] BBB Rating are considered as moderate-credit-quality Rating assigned by ICRA Nepal. The rated entity carries higher than average credit risk. The Rating is only an opinion on the general creditworthiness of the rated entity and not specific to any particular debt instrument. ICRA Nepal has also assigned rating of [ICRANP] LBBB (pronounced ICRA NP L triple B) to subordinated bonds of NRs 500 million of NMB. Instruments with [ICRANP] LBBB Rating are considered to have moderate degree of safety regarding timely servicing of financial obligations. Such instruments carry moderate credit risk. The ratings of NMB factors in the bank’s experienced senior management, adequate capitalisation level (CRAR of 11.63% as on mid-Jan-14), control on asset quality profile (Gross NPL of 1.59% as on Jan- 14), adequate earnings profile (PAT/ATA of 1.65% during FY13 and 1.54% during H1FY14), established network in terms of geographical presence. These positives are however offset in part by inferior deposit profile compared to industry average (NMB’s CASA deposit of around 31% as on Jan-14), high top depositors & credit concentration (top 20 depositors accounting for 44% of total deposits and top 20 borrowers accounting 30% of total credit as on Jan-14), low seasoning of significant credit book as the bank’s credit book grown significantly over last two years (credit book from NPR. -

Investment in Agricultural Mechanization in Africa

cover_I2130E.pdf 1 04/04/2011 17:45:11 AGRICULTURAL ISSN 1814-1137 AND FOOD ENGINEERING 8 AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD ENGINEERING TECHNICAL REPORT 8 TECHNICAL REPORT 8 Investment in agricultural mechanization in Africa Conclusions and recommendations of a Round Table Meeting of Experts Many African countries have economies strongly dominated by the agricultural sector and in some this generates a Investment in agricultural significant proportion of the gross domestic product. It provides employment for the majority of Africa’s people, but mechanization in Africa investment in the sector remains low. One of the keys to successful development in Asia and Latin America has been mechanization. By contrast, the use of tractors in sub-Saharan Investment in agricultural mechanization Africa Africa (SSA) has actually declined over the past fourty years Conclusions and recommendations and, compared with other world regions, their use in SSA of a Round Table Meeting of Experts today remains very limited. It is now clear that, unless some positive remedial action is taken, the situation can only worsen. In most African countries there will be more urban C dwellers than rural ones in the course of the next two to M three decades. It is critical to ensure food security for the Y entire population but feeding the increasing urban CM population cannot be assured by an agricultural system that MY is largely dominated by hand tool technology. CY In order to redress the situation, FAO, UNIDO and many CMY African experts are convinced that support is urgently needed K for renewed investment in mechanization. Furthermore, mechanization is inextricably linked with agro-industrialization, and there is a need to clarify the priorities in the context of a broader agro-industrial development strategy. -

Urban Expansion in Zanzibar City, Tanzania

1 Urban expansion in Zanzibar City, Tanzania: Analyzing quantity, spatial patterns and effects of 2 alternative planning approaches 3 4 MO Kukkonen, MJ Muhammad, N Käyhkö, M Luoto 5 6 Land Use Policy, 2018 - Elsevier 7 8 Abstract 9 Rapid urbanization and urban area expansion of sub-Saharan Africa are megatrends of the 21st century. 10 Addressing environmental and social problems related to these megatrends requires faster and more efficient 11 urban planning that is based on measured information of the expansion patterns. Urban growth prediction 12 models (UGPMs) provide tools for generating such information by predicting future urban expansion patterns 13 and allowing testing of alternative planning scenarios. We created an UGPM for Zanzibar City in Tanzania by 14 measuring urban expansion in 2004–2009 and 2009–2013, linking the expansion to explanatory variables with 15 a generalized additive model, measuring the accuracy of the created model, and projecting urban growth until 16 2030 with the business-as-usual and various alternative planning scenarios. Based on the results, the urban 17 area of Zanzibar City expanded by 40% from 2004 to 2013. Spatial patterns of expansion were largely driven 18 by the already existing building pattern and land-use constraints. The created model predicted future urban 19 expansion moderately well and had an area under the curve value of 0.855 and a true skill statistic result of 20 0.568. Based on the business-as-usual scenario, the city will expand 89% from 2013 until 2030 and will 21 continue to sprawl to new regions at the outskirts of the current built-up area. -

Population Dynamics and Social Policy

The Economic and Social Research Foundation (ESRF) is an independent policy research institution based in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. ESRF was established in 1994 to respond to the growing need for a research think tank with a mandate to conduct research for policy analysis and capacity building. The Foundation’s primary objectives are therefore to undertake policy-enhancing research, strengthen capabilities in policy analysis and decision making, as well as articulate and improve the understanding of policy options in government, the public sector, the donor community, and the growing private sector, and civil society. Vision: Advancing knowledge to serve the public, the government, CSOs, and the private sector through sound policy research, capacity development initiatives, and advocating good development management practices. Mission: POPULATION DYNAMICS To become a national and regional centre of excellence in policy research and capacity development for policy analysis and development management. AND SOCIAL POLICY Objectives: The overall objective of ESRF is to conduct research in economic and social policy areas and development management, and use its research outcomes to facilitate the country’s capacity for economic development and social advancement. By: Alfred Agwanda Otieno, Haidari K.R. Amani “This ESRF Discussion Paper is based on the output of the Tanzania Human Development Report 2017” and Ahmed Makbel THDR 2017: Background Paper No. 3 ESRF Discussion Paper 65 2016 www.esrftz.org POPULATION DYNAMICS AND SOCIAL POLICY By Alfred Agwanda Otieno, Haidari K.R. Amani and Ahmed Makbel THDR 2017: Background Paper No. 3 ISBN 978-9987-770-18-2 @ 2016 Economic and Social Research Foundation ESRF Discussion Paper No. -

Trust Funds Presentation

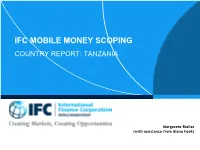

IFC MOBILE MONEY SCOPING COUNTRY REPORT: TANZANIA Margarete Biallas (with assistance from Alana Fook) TANZANIA SUMMARY - PAGE 1 CURRENT MOBILE MONEY SOLUTION Currently 5 mobile money solutions offered. POPULATION 51 million MOBILE PENETRATION 55% (high) BANKED POPULATION 19% through financial institutions, 40% overall [Source: World Bank FINDEX] PERCENT UNDER POVERTY LINE 28.2% (2012) [Source: World Bank] ECONOMICALLY ACTIVE POPULATION Workforce: 26.11 million (2015) [Source: CIA] ADULT LITERACY 70.6% of Tanzanians, age 15 and over, can read and write (2015) [Source: CIA] MOBILE NETWORK OPERATORS Vodacom (12.4 million subscribers) Tigo (11.4 million subscribers) Airtel (10.7 million subscribers) Zantel (1.2 million subscribers) There are smaller MNO’s eg Halotel (4%), Smart (3%) and TTCL (1%) but they are marginal and do not currently Market Readiness offer mobile money at this time. OVERALL READINESS RANKING The telcom sector has dramatically improved access Regulation 3 through mobile money. Over 40% of mobile money Financial Sector 3 subscribers are active on a 90-day basis. The financial Telecom Sector 4 sector has begun to incorporate agency banking into their channel strategies. Scope for improvements in Distribution 3 strategy formulation and execution exists. Distribution Market Demand 4 in rural areas is difficult as population density is low and infrastructure is poor. 4 (Moderate) Macro-economic Overview Regulations Financial Sector Telecom Sector Other Sectors Digital Financial Services Landscape MOBILE BANKING MARKET POTENTIAL