Meet Your Dog 2 3 Meet Your Dog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule Is Subject to Change Carolina Dog Judges Study Group

Schedule is Subject to Change Carolina Dog Judges Study Group Hound Breeds - Seminars and Workshops Registration TD Convention Center; 1 Exposition Avenue; Greenville, SC – July 2021 NAME_______________________________________ Judges #___________ ADDRESS_______________________________________________________ CITY_________________________ STATE _______ ZIP CODE ___________ Email Phone Please circle each breed that you expect to attend. This will help our presenters ensure that they have the proper amount of handout materials available. Schedule is subject to changes/adjustments. Thursday, July 29, 2021 9:00 to 11:45 am Basset Hound – presented by Kitty Steidel 12:00 to 2:30 pm Grand Bassets Griffons Vendeen - presented by Kitty Steidel 2:30 to 5:00 pm Petit Basset Griffon Vendeen - presented by Kitty Steidel 5:00 to 7:30 pm Basset Fauve de Bretagnes by Cindy Hartman Friday, July 30, 2021 9:00 to 11:30 am Cirneco dell’Etna – presented by Lucia Prieto 12:00 to 2:30 pm Greyhound presented by Patty Clark 2:30 to 5:00 pm Pharaoh Hound presented by Sheila Hoffman 5:00 – 7:30 pm Harrier presented by Kevin Shupenia Saturday, July 31, 2021 8:00 to 10:30 am Whippet – presented by Gail Boyd and Suzie Hughes 10:30 to 1:30 pm Borzoi - presented by Patti Neale 2:00 to 4:30 pm Scottish Deerhound -presented by Lynn Kiaer 4:30 to 7:00 pm Azawakh – presented by Fabian Arienti Sunday, August 1, 2021 8:30 to 11:00 am Basenji presented by Marianne Klinkowski 12:00 to 2:30 pm English Foxhound presented by Kevin Shupenia 2:30 to 5:00 pm American Foxhound presented by Polly Smith and Lisa Miller Return your completed application along with the payment of $60.00 per day ($75 per day payable after July 1, 2021) to: Cindy Stansell - 2199 Government Road, Clayton, NC 27520. -

Chrti Psi Bez Srsti

OBSAH Pošťáci 81 Eurasier 151 Psí burlaci 82 Šiperka 153 PE S 11 Závody saňových psů 82 Sibiřský husky 84 CHRTI Potom ek vlka 12 Aljašský malamut 88 Psí geny říkají něco jiného, než psí Sam ojed 90 Chrti východní, chrti západní 156 kosti 13 Grónský pes 93 Princip ucha 156 Genom psa 15 Kanadský inuitský pes 95 Tajemství skalního města 160 Vznik plemen a jejich Americký eskymácký pes 96 Šakalové, hyeny, chrti a bozi 161 klasifikace 18 Alaskáni a spol 96 Psi faraónů a „faraónský chrt" 164 První systematická nomenklatura Alaskan husky 97 Tesem 166 psů 18 C h in o o k 97 Faraónský chrt 166 Genetické skupiny 20 Evropský saňový pes 99 Domorodí chrti Indie 168 Plem ena 20 Z historie saňových psů Rampúrský chrt 168 v Čechách 100 Rajapalayam (Poligar) 169 DOMESTIKACE 21 S Byrdem na Jižní točnu 100 Čippiparai 169 Český horský pes 104 Pašm i 169 Když vlk sklopil uši 21 Kuči 169 Kdo si koho ochočil 21 Severští lovečtí špicové 107 Banjara 169 Domestikace 22 Norský losí pes šedý 110 Venuše a psi 24 Norský losí pes černý 110 Chrti Afriky a Asie 170 „Bez psa by člověk zůstal opicí" 24 Švédský losí pes 112 Afghánský chrt 170 Cesty psů jsou cestami lidí 28 Švédský bílý elkhound 112 Saluki 173 Pes v Evropě a zemědělství 29 Hälleforshund 112 Sloughi 175 Nejstarší historie psa v datech 32 Norský lundehund 113 Azavak 178 Zařazení plemen podle nomenkla Lajka ruskoevropská 115 Barzoj 180 tury FCI 34 Lajka západosibiřská 115 Chortaja borzaja 183 Lajka východosibřská 115 Tazi 185 SENSI PSI a PÁRIOVÉ 39 Lajka ruskofinská 115 Tajgan 186 Karelský medvědí pes 118 -

Secretary's Pages

SECRETARY ’S PAGES MISSION STATEMENT The American Kennel Club is dedicated to upholding the T ATENTION DELEGATES integrity of its RMegIisStrSy, IpOroNmo ting the spSorTt Aof TpEurMebrEeNd dT ogs and breeding for type and function. ® NOTICE OF MEETING TFohuen Admederiin ca1n8 8K4e, ntnhelAKC Cluba nisd dites daicffailtieadte td o ourpghaonlidziantgio nths ea idnvteogcarittey foofr iths e Rpeugriset brrye, dp rdoomgo atisn ga tfhame islyp ocrot mofpapnuiroenb,r ead vdaongcs e acnad nibnree ehdeianlgthf oarndty pwe elal-nbd eifnugn,c wtioonrk. to protect the rights of all Fdougn odwedneinrs1 a8n8d4 ,ptrhoe mAKCote raensd piotns saifbflieli adtoegd orwgnaenrizsahtipio. ns advocate for the pure bred dog as a The next meeting of the Delegates will be held family companion, advance canine health and well-being, work to protect the rights of all dog owners and 805prom1 oAtrec ore Csopropnosribaltee dDorgiv oew, Snueirtseh 1ip0. 0, Raleigh, NC 276 17 at the Doubletree Newark Airport Hotel on 101 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10178 8051 Arco Corporate Drive, Suite 100, Raleigh, NC 276 17 Tuesday Raleigh, NC Customer Call Center ..............................................................(919) 233-9767 260 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 , September 10, 2019. For the sole pur- New York, NY Office ...................................................................................(212) 696-8200 Raleigh, NC Customer Call Center ..............................................................(919) 233-9767 Fax .............................................................................................................(212) -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

BCOA Bulleint May-June-July-August 2017

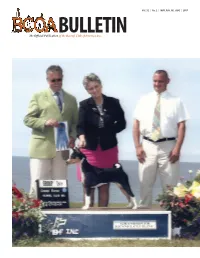

Vol. 52 | No. 2 | MAY JUN JUL AUG | 2017 Th e Offi cial PublicationBULLETIN of the Basenji Club of America, Inc. cvr2 BCOA Bulletin (MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2017) visit us online at www.basenji.org www.facebook.com/basenji.org BCOA Bulletin (MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2017) 1 2 BCOA Bulletin (MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2017) visit us online at www.basenji.org www.facebook.com/basenji.org BCOA Bulletin (MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2017) 3 BCOA BULLETIN Tootsie’s get is as follows in the order they fi nished: CONTENTS MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2017 1. BISS Ch. Taji’s Klassic Beauty – #1 bitch in 2005, AOM and Best Veteran at national 2. Am/Int. UKC Ch. Klassic’s Hot Ticket to Berimo – WB 2004 national at 9 mos. Old. 3. Am/Eng. MBISS/MBIS Klassic’s Million Dollar Baby at Tokaji – Millie has broken every record in the UK, won Cruft s best of breed 5 times, Top Basenji, Top Hound and 2 times Top Brood On the cover bitch all breeds. 4. DC Taji’s Klassic Architecture SC SDHR – Finished at 8 mos of age at the EBC specialty, Tootsie WWWHA grand sweep winner of over 100 hounds. MBIS/BISS CDN/MBISS CH. KLASSIC’S ROOT TOOT TOOT 5. Ch. Klassic’s Hot to Trot to Naharin – fi nished with all majors and lives on the couch in CA. 6. DC Klassic’s Ms Mata Hauri SC – best in sweeps at the 2005 national, BOB at the 2006 national, 7 time BIS winner (holds record for top bitch), 2 time BOB winner Westminster KC – lives in Who doesn’t know the name Tootsie??? Tootsie had a wonderful show career – NH on Debbie’s couch. -

Dog Breeds Pack 1 Professional Vector Graphics Page 1

DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 1 Affenpinscher Afghan Hound Aidi Airedale Terrier Akbash Akita Inu Alano Español Alaskan Klee Kai Alaskan Malamute Alpine Dachsbracke American American American American Akita American Bulldog Cocker Spaniel Eskimo Dog Foxhound American American Mastiff American Pit American American Hairless Terrier Bull Terrier Staffordshire Terrier Water Spaniel Anatolian Anglo-Français Appenzeller Shepherd Dog de Petite Vénerie Sennenhund Ariege Pointer Ariegeois COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 2 Armant Armenian Artois Hound Australian Australian Kelpie Gampr dog Cattle Dog Australian Australian Australian Stumpy Australian Terrier Austrian Black Shepherd Silky Terrier Tail Cattle Dog and Tan Hound Austrian Pinscher Azawakh Bakharwal Dog Barbet Basenji Basque Basset Artésien Basset Bleu Basset Fauve Basset Griffon Shepherd Dog Normand de Gascogne de Bretagne Vendeen, Petit Basset Griffon Bavarian Mountain Vendéen, Grand Basset Hound Hound Beagle Beagle-Harrier COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 2 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 3 Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bearded Collie Beauceron Bedlington Terrier (Tervuren) Dog (Groenendael) Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bergamasco Dog (Laekenois) Dog (Malinois) Shepherd Berger Blanc Suisse Berger Picard Bernese Mountain Black and Berner Laufhund Dog Bichon Frisé Billy Tan Coonhound Black and Tan Black Norwegian -

Dog Breeds in Groups

Dog Facts: Dog Breeds & Groups Terrier Group Hound Group A breed is a relatively homogeneous group of animals People familiar with this Most hounds share within a species, developed and maintained by man. All Group invariably comment the common ancestral dogs, impure as well as pure-bred, and several wild cousins on the distinctive terrier trait of being used for such as wolves and foxes, are one family. Each breed was personality. These are feisty, en- hunting. Some use created by man, using selective breeding to get desired ergetic dogs whose sizes range acute scenting powers to follow qualities. The result is an almost unbelievable diversity of from fairly small, as in the Nor- a trail. Others demonstrate a phe- purebred dogs which will, when bred to others of their breed folk, Cairn or West Highland nomenal gift of stamina as they produce their own kind. Through the ages, man designed White Terrier, to the grand Aire- relentlessly run down quarry. dogs that could hunt, guard, or herd according to his needs. dale Terrier. Terriers typically Beyond this, however, generali- The following is the listing of the 7 American Kennel have little tolerance for other zations about hounds are hard Club Groups in which similar breeds are organized. There animals, including other dogs. to come by, since the Group en- are other dog registries, such as the United Kennel Club Their ancestors were bred to compasses quite a diverse lot. (known as the UKC) that lists these and many other breeds hunt and kill vermin. Many con- There are Pharaoh Hounds, Nor- of dogs not recognized by the AKC at present. -

Genetic Structure in Village Dogs Reveals a Central Asian Domestication Origin

Genetic structure in village dogs reveals a Central Asian domestication origin Laura M. Shannona, Ryan H. Boykob, Marta Castelhanoc, Elizabeth Coreyc, Jessica J. Haywarda, Corin McLeand, Michelle E. Whitea, Mounir Abi Saide, Baddley A. Anitaf, Nono Ikombe Bondjengog, Jorge Caleroh, Ana Galovi, Marius Hedimbij, Bulu Imamk, Rajashree Khalapl, Douglas Lallym, Andrew Mastan, Kyle C. Oliveiraa, Lucía Pérezo, Julia Randallp, Nguyen Minh Tamq, Francisco J. Trujillo-Cornejoo, Carlos Valerianoh, Nathan B. Sutterr, Rory J. Todhunterc, Carlos D. Bustamantes, and Adam R. Boykoa,1 aDepartment of Biomedical Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; bDepartment of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases, Yale School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06510; cDepartment of Clinical Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; dBiogen Idec, Cambridge, MA 02142; eBiology Department, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; fHoniara Veterinary Clinic and Surgery, Honiara, Solomon Islands; gDépartement de l’environnement, Faculté des Sciences, Université de Mbandaka, Mbandaka, Democratic Republic of Congo; hAcadémico de Arqueologia, Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, Cusco, Peru; iDepartment of Animal Physiology, University of Zagreb, Zagreb 10000, Croatia; jMicrobiology, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia; kSanskriti Centre, Hazaribagh, Jharkhand, India 825 301; lThe INDog Project, Maharashtra, India; mThe Mongolian Bankhar Project, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia; nSchool of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Papua New Guinea, Boroko, Port Moresby, National Capital District, 111, Papua New Guinea; oInstituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Federal District, Mexico; pUniversity of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA 01655; qVietnam National Museum of Nature, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, Vietnam; rDepartment of Biology, La Sierra University, Riverside, CA 92505; and sDepartment of Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305 Edited by David M. -

E O Cial Publication of the Basenji Club of America, Inc

Vol.51 | No. 2 | MAY JUN JUL AUG | 2016 e O cial Publication BULLETINof the Basenji Club of America, Inc. BCOA BULLETIN CONTENTS MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2016 On the cover JAYDA Nailah in That Lil Red Dress For Woodella Bred by: Christine Petersen Owned by: Tom Rabbi e & Charley Donaldson Handled by: Charley Donaldson West of England Ladies Kennel Society (WELKS), Malvern, England 2016. Jayda was awarded Best Any Variety Puppy. Cru s, Birmingham, England 2016. Jayda was awarded Best Of Breed, Best Puppy, and Bitch Challenge Certi cate. Cover Photo: George Waddell, om WELKS show. Photo at right: V.L. Gaskell FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 7 Calendar of Events 20 A LIFETIME MEMBER PROFILE DR. STEVE GONTO 8 About this Issue BY DR. STEVE GONTO, WITH HOLLY HAMILTON 9 Contributors 26 CELEBRATION OF DOGS 10 Letter from the President CRUFTS ENGLAND 1891-2016 12 Training Tips BY ETHEL BLAIR 13 Juniors 30 A JUDGE’S POINT OF VIEW AKC & ASFA LURE COURSING JUDGING BY HOLLY HAMILTON REPORTS 32 SPORTSMANSHIP BY GREGORY ALDEN BETOR 14 Committee Reports 35 VALE JOHN EDWARD VALK 16 Affi liate Club Reports A TRIBUTE 18 Basenji Foundation Stock Applicants BY COLLABORATION cvr2 BCOA Bulletin (MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2016) visit us online at www.basenji.org www.facebook.com/basenji.org BCOA Bulletin (MAY/JUN/JUL/AUG 2016) 1 It’s never too late to celebrate your wins (or the cuteness). BULLETIN Let the world know you’re proud of your hound with an ad in the Bulletin. e O cial Publication Best value around. of the Basenji Club of America, Inc. -

The Intelligence of Dogs a Guide to the Thoughts, Emotions, and Inner Lives of Our Canine

Praise for The Intelligence of Dogs "For those who take the dog days literally, the best in pooch lit is Stanley Coren’s The Intelligence of Dogs. Psychologist, dog trainer, and all-around canine booster, Coren trots out everyone from Aristotle to Darwin to substantiate the smarts of canines, then lists some 40 commands most dogs can learn, along with tests to determine if your hairball is Harvard material.” —U.S. News & World Report "Fascinating . What makes The Intelligence of Dogs such a great book, however, isn’t just the abstract discussions of canine intelli gence. Throughout, Coren relates his findings to the concrete, dis cussing the strengths and weaknesses of various breeds and including specific advice on evaluating different breeds for vari ous purposes. It's the kind of book would-be dog owners should be required to read before even contemplating buying a dog.” —The Washington Post Book World “Excellent book . Many of us want to think our dog’s persona is characterized by an austere veneer, a streak of intelligence, and a fearless-go-for-broke posture. No matter wrhat your breed, The In telligence of Dogs . will tweak your fierce, partisan spirit . Coren doesn’t stop at intelligence and obedience rankings, he also explores breeds best suited as watchdogs and guard dogs . [and] does a masterful job of exploring his subject's origins, vari ous forms of intelligence gleaned from genetics and owner/trainer conditioning, and painting an inner portrait of the species.” —The Seattle Times "This book offers more than its w7ell-publicized ranking of pure bred dogs by obedience and working intelligence. -

Domestic Dog Breeding Has Been Practiced for Centuries Across the a History of Dog Breeding Entire Globe

ANCESTRY GREY WOLF TAYMYR WOLF OF THE DOMESTIC DOG: Domestic dog breeding has been practiced for centuries across the A history of dog breeding entire globe. Ancestor wolves, primarily the Grey Wolf and Taymyr Wolf, evolved, migrated, and bred into local breeds specific to areas from ancient wolves to of certain countries. Local breeds, differentiated by the process of evolution an migration with little human intervention, bred into basal present pedigrees breeds. Humans then began to focus these breeds into specified BREED Basal breed, no further breeding Relation by selective Relation by selective BREED Basal breed, additional breeding pedigrees, and over time, became the modern breeds you see Direct Relation breeding breeding through BREED Alive migration BREED Subsequent breed, no further breeding Additional Relation BREED Extinct Relation by Migration BREED Subsequent breed, additional breeding around the world today. This ancestral tree charts the structure from wolf to modern breeds showing overlapping connections between Asia Australia Africa Eurasia Europe North America Central/ South Source: www.pbs.org America evolution, wolf migration, and peoples’ migration. WOLVES & CANIDS ANCIENT BREEDS BASAL BREEDS MODERN BREEDS Predate history 3000-1000 BC 1-1900 AD 1901-PRESENT S G O D N A I L A R T S U A L KELPIE Source: sciencemag.org A C Many iterations of dingo-type dogs have been found in the aborigine cave paintings of Australia. However, many O of the uniquely Australian breeds were created by the L migration of European dogs by way of their owners. STUMPY TAIL CATTLE DOG Because of this, many Australian dogs are more closely related to European breeds than any original Australian breeds. -

Canis-Adn-Mix Razas Caninas

CANIS-ADN-MIX RAZAS CANINAS Affenpinscher Bohemian Shepherd Afghan Hound Bolognese Airedale Terrier Border Collie Akita Border Terrier Alaskan Klee Kai Borzoi Alaskan Malamute Boston Terrier Alpine Dachsbracke Bouvier Des Flanders American English Coonhound Boxer American Eskimo Dog Boykin Spaniel American Foxhound Bracco Italiano American Hairless Rat Terrier Braque du Bourbonnais American Indian Dog Brazilian Terrier American Staffordshire Terrier Briard American Water Spaniel Brussels Griffon Anatolian Shepherd Dog Bulgarian Shepherd Appenzell Cattle Dog Bull Arab Argentine Dogo Bull Terrier (Miniature) Australian Cattle Dog Bull Terrier (Standard) Australian Kelpie Bulldog (American) Australian Labradoodle Bulldog (Standard) Australian Shepherd Bullmastiff Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog Cairn Terrier Australian Terrier Canaan Dog Azawakh Canadian Eskimo Dog Barbet Cane Corso Basenji Cardigan Welsh Corgi Basset Bleu de Gascogne Catahoula Leopard Dog Basset Fauve de Bretagne Catalan Sheepdog Basset Griffon Vendeen (Grand) Caucasian Shepherd Dog Basset Griffon Vendeen (Petit) Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Basset Hound Central Asian Ovcharka Bavarian Mountain Hound Cesky Terrier Beagle Chesapeake Bay Retriever Bearded Collie Chihuahua Beauceron Chinese Crested Bedlington Terrier Chinese Shar-Pei Belgian Malinois Chinook Belgian Mastiff Chow Chow Belgian Sheepdog Cirneco del Etna Belgian Tervuren Clumber Spaniel Bergamasco Cocker Spaniel Berger Picard Collie Bernese Mountain Dog Continental Toy Spaniel (phalene and papillon) Bichon