Roles, Missions and Business Models of Public Financial Institutions in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(EFT)/Automated Teller Machines (Atms)/Other Electronic Termi

Page 1 of 1 Effective as of 11/23/18 Information About Your Ulster Savings Bank Money Market Account Balance to Open Your Money Market Account must be opened with a minimum deposit of $2,500.00 Balance to Earn Interest If your daily balance is less than $2,500.00, you will earn the Interest Rate and Annual Percentage Yield in effect, as disclosed to you under separate cover, on the entire balance in your account. If your daily balance is $2,500.00 or more you will earn the higher Interest Rate and Annual Percentage Yield in effect, as disclosed to you under separate cover, on the entire balance in your account. Balance to Avoid Fees Your daily balance for every day of the statement cycle period must be at least $2,500.00 to avoid the imposition of a maintenance fee for that period. Variable Rate Features This is a variable rate account. Your Interest Rate and Annual Percentage Yield may change. The Interest Rate is set based on the Bank's discretion and may change at any time at the Bank's discretion. Interest Computation We use the daily balance method to calculate interest on your account. This method applies a periodic rate to the balance in the account each day. Compounding Period Interest compounds on your account daily, using a 365/360 interest factor. Interest Accrual Interest begins to accrue on the business day you deposit non-cash items, such as checks. Although your account may earn interest each day, you may not withdraw the earnings until the end of the interest crediting period (see Payment of Interest). -

Postal Giro System ▪ History and a Bit of Economics ⚫ CBDC V Postal Giro

Central bank digital currency is evolution, not revolution – also across borders Morten Bech Swissquote Conference 2020 on Finance and Technology, EFPL, 30 October 2020 The views in this presentation are those of the presenter and not necessarily those of the BIS Restricted Restricted 2 CBDCs are hot stuff Hyperlink BIS CBDCs: the next hype or the future of payments? Graph 1 Timing of speeches and reports on CBDC1 Google search interest over time2 Number of speeches Search interest by year, index 1 12-month moving sum of the count of central bankers’ speeches resulting from a case-insensitive search for any of the following words/phrases: CBDC; central bank digital currency; digital currency and digital money. 2 12-week moving average of worldwide search interest. The data has been normalised to the 12-week moving average peak of each series. The search was run on search terms “Bitcoin” and “Facebook Libra” and topic “Central Bank Digital Currency”. Data accessed on 16 July 2020. Sources: R Auer, G Cornelli and J Frost, "Rise of the central bank digital currencies: drivers, approaches and technologies", BIS Working Papers, no 880, August 2020. Restricted 3 Key features of a retail CBDC = target or aspiration CBDC CBDC CBDC ✓ State issued Scalable High availability 1:1 Singleness of Fast Cross currency border Ease of use Legal framework Offline Restricted 4 Game plan ⚫ A simple view of payment systems ▪ Front-end, network and back-end ⚫ Innovation and payment systems ▪ Network is key ⚫ Postal giro system ▪ History and a bit of economics ⚫ CBDC v Postal giro Restricted 5 Payment system = front-end, network and back-end Payer Payee Network Back-end Network front-end front-end Restricted 6 A simple example to fix ideas Real time gross settlement system Bank A Network Central Network Bank B bank RTGS Restricted 7 Unpacking the back-end: Gold transfers between central banks Settlement asset Transfer mechanism Central Network Network Central bank A Bank B Federal Reserve Bank of New York Settlement agent [email protected] . -

Achments Or Click on the Link from Unsolicited Sources

Thomaston Savings Bank Business Online Banking Guide Member FDIC Welcome A quick and Easy Guide to Business Online Banking Whether you’re at home, at work or on the road, we are here for you 24 hours a day, 7 days a week with our Online Banking & Bill Payment Services. This guide is designed to help you answer your questions about Thomaston Savings Bank’s Online Banking. Experience the convenience of having 24‐hour access to real‐time account information from your computer and mobile device. Online Banking is convenient, easy to use, and more secure than ever. In addition to accessing your account information and transferring funds online, you’ll also be able to export account information to financial management software, such as Quicken® or QuickBooks® direct connect, and pay your bills online. We appreciate your business and are committed to providing you with the best possible banking experience. Business Online Banking Guide | 1 Security By following our tips, Business Online Banking can be a safe and efficient method for handling your banking needs. User Identification and Password Security starts at your computer. Never share your Login ID or password with anyone. Make sure your password is hard to guess by combining random numbers and letters instead of using your birth date, pet’s name, or other obvious clues. Secure Sockets Layer Encryption (SSL) This technology scrambles data as it travels between your computer and our system, making it difficult for anyone to access your account information. SSL is a trusted method of securing internet transactions. Browser Registration In addition to your personal password security, your financial institution has added additional security measures with Brower Registration. -

(2019). Bank X, the New Banks

BANK X The New New Banks Citi GPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions March 2019 Citi is one of the world’s largest financial institutions, operating in all major established and emerging markets. Across these world markets, our employees conduct an ongoing multi-disciplinary conversation – accessing information, analyzing data, developing insights, and formulating advice. As our premier thought leadership product, Citi GPS is designed to help our readers navigate the global economy’s most demanding challenges and to anticipate future themes and trends in a fast-changing and interconnected world. Citi GPS accesses the best elements of our global conversation and harvests the thought leadership of a wide range of senior professionals across our firm. This is not a research report and does not constitute advice on investments or a solicitations to buy or sell any financial instruments. For more information on Citi GPS, please visit our website at www.citi.com/citigps. Citi Authors Ronit Ghose, CFA Kaiwan Master Rahul Bajaj, CFA Global Head of Banks Global Banks Team GCC Banks Research Research +44-20-7986-4028 +44-20-7986-0241 +966-112246450 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Charles Russell Robert P Kong, CFA Yafei Tian, CFA South Africa Banks Asia Banks, Specialty Finance Hong Kong & Taiwan Banks Research & Insurance Research & Insurance Research +27-11-944-0814 +65-6657-1165 +852-2501-2743 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Judy Zhang China Banks & Brokers Research +852-2501-2798 -

Pa Perspectives on Nordic Financial Services

PA PERSPECTIVES ON NORDIC FINANCIAL SERVICES Autumn Edition 2017 CONTENTS The personal banking market 3 Interview with Jesper Nielsen, Head of Personal Banking at Danske bank Platform thinking 8 Why platform business models represent a double-edged sword for big banks What is a Neobank – really? 11 The term 'neobanking' gains increasing attention in the media – but what is a neobank? Is BankID positioned for the 14future? Interview with Jan Bjerved, CEO of the Norwegian identity scheme BankID The dance around the GAFA 16God Quarterly performance development 18 Latest trends in the Nordics Value map for financial institutions 21 Nordic Q2 2017 financial highlights 22 Factsheet 24 Contact us Chief editors and Nordic financial services experts Knut Erlend Vik Thomas Bjørnstad [email protected] [email protected] +47 913 61 525 +47 917 91 052 Nordic financial services experts Göran Engvall Magnus Krusberg [email protected] [email protected] +46 721 936 109 +46 721 936 110 Martin Tillisch Olaf Kjaer [email protected] [email protected] +45 409 94 642 +45 222 02 362 2 PA PERSPECTIVES ON NORDIC FINANCIAL SERVICES The personal BANKING MARKET We sat down with Jesper Nielsen, Head of Personal Banking at Danske Bank to hear his views on how the personal banking market is developing and what he forsees will be happening over the next few years. AUTHOR: REIAR NESS PA: To start with the personal banking market: losses are at an all time low. As interest rates rise, Banking has historically been a traditional industry, loss rates may change, and have to be watched. -

Interbank GIRO Is an Automated Payment Service Which Allows You to Make Monthly Payment to Your ICBC Credit Card Account from Your Designated Bank Account Directly

Interbank GIRO Frequently Asked Questions: 1. What is Interbank GIRO? Interbank GIRO is an automated payment service which allows you to make monthly payment to your ICBC Credit Card account from your designated bank account directly. The amount will be deducted from your designated bank account and paid to ICBC every month. All you need to do is to ensure that the designated bank account has sufficient funds every month. 2. What is the benefit of using Interbank GIRO? Interbank GIRO is a convenient, paperless and cashless payment method. It enables you to make hassle-free monthly payments to ICBC through your designated bank account. There are also no fees charged for the setup. 3. Are there any additional charges for signing up for Interbank GIRO? There are no fees charged for the setup of Interbank GIRO. 4. How can I apply for Interbank GIRO? Simply fill up the Interbank GIRO form, and submit to Credit Card Department. 5. Which banks can I use for Interbank GIRO? You can use any bank that supports Interbank GIRO. 6. How long is the Interbank GIRO application Processing Time? Interbank GIRO applications may take up to 60 days to process, including the processing time required by the deducting bank. We will notify you of your application status as soon as possible. 7. How do I submit the Interbank GIRO form to ICBC Credit Card Department? You can mail the duly signed Original Interbank GIRO form to ICBC Credit Card Department by using the Business Reply Service Envelope attached. Please do not fax the Interbank GIRO form or email the scanned copy of the Interbank GIRO form as the designated bank requires the original signature for verification. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Page TERMS and CONDITIONS of YOUR ACCOUNT

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF YOUR ACCOUNT ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Important Information About Procedures for Opening a New Account ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Agreement....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Liability ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Deposits .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Withdrawals..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Understanding and Avoiding Overdraft and Nonsufficient Funds (NSF) Fees............................................................................................................................... -

Building a Customer-Centric Digital Bank in Singapore: It Takes an Ecosystem

White Paper Digital Banking EQUINIX AND KAPRONASIA BUILDING A CUSTOMER-CENTRIC DIGITAL BANK IN SINGAPORE: IT TAKES AN ECOSYSTEM Contents The dawn of digital banking in the Lion City Defining a value proposition . 2 No digital bank, in the purest sense of the term, Digital banking in Singapore amid COVID-19 . 4 currently exists in Singapore. While there are many fintechs, most provide only digital financial services The digital banking opportunity: that do not require a banking license: digital wallet retail and corporate . 5 services, cross-border payments and various virtual- asset-focused services. A digital bank (also known Key success factors for digital banks . 7 as a “neobank” or “virtual bank”) differs in that it is licensed to both accept customer deposits and issue 1. Digital agility to support a better loans, whether to retail customers, corporate customers customer experience. .7 or both. Singapore’s financial regulator, the Monetary 2. Favorable cost structure. .8 Authority of Singapore (MAS) plans to release five digital bank licenses in total and will announce the 3. Optimizing security .............................8 successful licensees in the second half of 2020. The licensed digital banks will likely then launch in mid-2021. Conclusion: The ecosystem opportunity . 10 While many less-developed Southeast Asian economies are leveraging digital banks to focus on financial inclusion, the role of digital banks in Singapore will be slightly different and focused on driving innovation. Bringing together traditional financial services firms, fintechs, other tech companies and even telecoms Singapore will become one of the firms, digital banks could act as a catalyst for financial focal points of Asia’s digital banking innovation in Singapore and help the city-state maintain evolution when the city-state awards its competitive advantage as a regional fintech hub. -

World Bank Document

69464 Public Disclosure Authorized The Role of Postal Networks in Expanding Access to Financial Services Worldwide Landscape of Postal Financial Services Middle East and North Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Group Global Information and Communication Technology Postbank Advisory, ING Bank Postal Policy Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Worldwide Landscape of Postal Financial Services _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Author’s Note This section discusses the landscape of postal networks in the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA) and their current role in providing access to financial services. The landscape is intended to serve as a basis to assess their potential to expand access to financial services. For this purpose, eight countries in the region were pre-selected for further analysis. The main assumption was that these countries have postal networks actively involved in providing financial services. The countries have diverse backgrounds, market contexts, institutional constellations, and development of their respective postal networks. For some aspects and some countries (e.g., Libya, Syria), data was not available, or only to a limited extent, by the desk research finished in 2004. In particular, this concerns data for the role of the postal networks in the cashless payment systems, the significance of the postal financial services compared to monetary aggregates, and the details of the financial services rendered -

Consumer Electronic Funds Transfer (“Eft”) and Debit Card Agreement

CONSUMER ELECTRONIC FUNDS TRANSFER (“EFT”) AND DEBIT CARD AGREEMENT “We,” “us” and “our” refer to Union Savings Bank. “You” and “your” apply to any individual who has an Account with us and is authorized to initiate the applicable EFTs. “Account” refers to any account at our bank from or to which we allow electronic funds transfers (“EFTs ”) and that you have selected in your application for the EFT service. “ATM” refers to any automated teller machines where you can use your card and PIN. “Available Funds or Available Balance” means the funds that are "available for withdrawal" as determined by our Funds Availability Policy. Your available balance may be reduced if we have placed "holds" on certain funds. A "hold" means that funds are still in your account but we will not allow you to withdraw them. A hold may be placed because of delayed funds availability as described in our Funds Availability Policy or because of a court order or a pending Debit Card transaction as described in our Consumer Electronic Funds Transfer and Debit Card Agreement . Additional funds may be available to you if you have Overdraft Protection. Please see your overdraft protection loan agreement for further information. “Card” refers to the Union Savings Bank ATM Card or the Union Savings Bank Debit Card. “Hold on Account-Debit Card” When you make a purchase with a debit card, you authorize us to place a hold on your account for the amount of the transaction. When the transaction has cleared, the hold will be released and the funds will be debited from your account. -

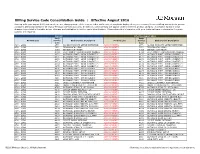

Billing Service Code Consolidation Guide | Effective August 2016

Billing Service Code Consolidation Guide | Effective August 2016 Starting with your August 2016 statement, we are changing some of the service codes and service descriptions displayed on your Treasury Services Billing statement to provide consistent billing standards for all of your Treasury Services accounts. In addition, some services will appear under a different product category. A complete listing of these changes is provided in the table below. Changes are highlighted in red for easier identification. Please share this information with your technical team to determine if system updates are required. Current Effective August 2016 Bank Bank Product Line Service Bank Service Description Product Line Service Bank Service Description Code Code ACH - GIRO 2770 ACHDD MANDATE SETUP(INITIATOR) ACH PAYMENTS 2770 ACHDD MANDATE SETUP(INITIATOR) ACH - GIRO 3971 ZENGIN ACH (LOW) ACH PAYMENTS 3971 ZENGIN ACH (LOW) ACH - GIRO 4093 ZENGIN ACH (HIGH) ACH PAYMENTS 4093 ZENGIN ACH (HIGH) ACH - GIRO 4094 ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CHARGE ACH PAYMENTS 4094 ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CHARGE ACH - GIRO 4170 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 1 ACH PAYMENTS 4170 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 1 ACH - GIRO 4171 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 2 ACH PAYMENTS 4171 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 2 ACH - GIRO 4172 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 3 ACH PAYMENTS 4172 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 3 ACH - GIRO 4173 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 4 ACH PAYMENTS 4173 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 4 ACH - GIRO 4174 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 5 ACH PAYMENTS 4174 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) -

Payment Services Guide

CitiDirect® Online Banking Payments Services Guide March 2004 Proprietary and Confidential These materials are proprietary and confidential to Citibank, N.A., and are intended for the exclusive use of CitiDirect ® Online Banking customers. The foregoing statement shall appear on all copies of these materials made by you in whatever form and by whatever means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or in any information storage system. In addition, no copy of these materials shall be disclosed to third parties without express written authorization of Citibank, N.A. Table of Contents Overview .......................................................................................................................................1 Payments Services....................................................................................................................1 Creating Service Requests From Transaction Lookup..............................................................2 Creating Service Requests From Transaction Details ..............................................................9 Modifying Service Requests....................................................................................................14 Authorizing or Deleting Service Requests...............................................................................16 Viewing Service Request Transactions...................................................................................18 Disclaimer ...................................................................................................................................20