Inner Mission North 1853-1943 Context Statement, 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. THEMES The chapters in this section take themes as their starting points. They explore different aspects of LGBTQ history and heritage, tying them to specific places across the country. They include examinations of LGBTQ community, civil rights, the law, health, art and artists, commerce, the military, sports and leisure, and sex, love, and relationships. MAKING COMMUNITY: THE PLACES AND15 SPACES OF LGBTQ COLLECTIVE IDENTITY FORMATION Christina B. Hanhardt Introduction In the summer of 2012, posters reading "MORE GRINDR=FEWER GAY BARS” appeared taped to signposts in numerous gay neighborhoods in North America—from Greenwich Village in New York City to Davie Village in Vancouver, Canada.1 The signs expressed a brewing fear: that the popularity of online lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) social media—like Grindr, which connects gay men based on proximate location—would soon replace the bricks-and-mortar institutions that had long facilitated LGBTQ community building. -

Hclassifi Cation

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) WEES UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME Bateria San Josej Punta Medanos; Battery Yerba Buena^ Point San Jose: HISTORIC Black Point; Post of Point San Jose; Fort Mason ,AND/OR COMMON =; — '"-''" Fort Mason LOCATION STREET&NUMBER ,,Qn the water*s edge, Northern San Francisco, bounded by Van Ness- Avenue, Bay -Sfea?e@*% and Laguna Streets,* _NOTFOR PUBLICATION / CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT San Francisco _ VICINITY OF Fifth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 San Francisco 075 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X_DISTRICT X_PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS X_EDUCATIONAL X_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED ^.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED .XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO X-MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS. (Itapplicable) National Park Service, Western Regional Office STREET & NUMBER 450 Golden Gate Avenue, Box 36063 CITY. TOWN STATE San Francisco VICINITY OF California COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. San Francisco City Hall STREET & NUMBER Polk and McAllister Streets CITY. TOWN STATE San Francisco California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey, GAL-1119 and CAL 1877-1880 DATE Late 1930 f s and January, 1959 .XFEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress CITY. TOWN STATE Washington District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —RUINS -^ALTERED —FAIR _UNEXPOSED (1 moved, 1877) DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE 7. -

Argonaut #2 2019 Cover.Indd 1 1/23/20 1:18 PM the Argonaut Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society Publisher and Editor-In-Chief Charles A

1/23/20 1:18 PM Winter 2020 Winter Volume 30 No. 2 Volume JOURNAL OF THE SAN FRANCISCO HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOL. 30 NO. 2 Argonaut #2_2019_cover.indd 1 THE ARGONAUT Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society PUBLISHER AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Charles A. Fracchia EDITOR Lana Costantini PHOTO AND COPY EDITOR Lorri Ungaretti GRapHIC DESIGNER Romney Lange PUBLIcatIONS COMMIttEE Hudson Bell Lee Bruno Lana Costantini Charles Fracchia John Freeman Chris O’Sullivan David Parry Ken Sproul Lorri Ungaretti BOARD OF DIREctORS John Briscoe, President Tom Owens, 1st Vice President Mike Fitzgerald, 2nd Vice President Kevin Pursglove, Secretary Jack Lapidos,Treasurer Rodger Birt Edith L. Piness, Ph.D. Mary Duffy Darlene Plumtree Nolte Noah Griffin Chris O’Sullivan Richard S. E. Johns David Parry Brent Johnson Christopher Patz Robyn Lipsky Ken Sproul Bruce M. Lubarsky Paul J. Su James Marchetti John Tregenza Talbot Moore Diana Whitehead Charles A. Fracchia, Founder & President Emeritus of SFHS EXECUTIVE DIREctOR Lana Costantini The Argonaut is published by the San Francisco Historical Society, P.O. Box 420470, San Francisco, CA 94142-0470. Changes of address should be sent to the above address. Or, for more information call us at 415.537.1105. TABLE OF CONTENTS A SECOND TUNNEL FOR THE SUNSET by Vincent Ring .....................................................................................................................................6 THE LAST BASTION OF SAN FRANCISCO’S CALIFORNIOS: The Mission Dolores Settlement, 1834–1848 by Hudson Bell .....................................................................................................................................22 A TENDERLOIN DISTRIct HISTORY The Pioneers of St. Ann’s Valley: 1847–1860 by Peter M. Field ..................................................................................................................................42 Cover photo: On October 21, 1928, the Sunset Tunnel opened for the first time. -

21St Annual 80Th Anniversary of SF General Strike

LaborFest 2014 80th Anniversary of SF General Strike 21st Annual Fighting For Survival July 5 - July 31 From Rockefeller to Tech Titans LABORFEST, P.O.Box 40983, San Francisco, CA 94140, (415) 642-8066 www.laborfest.net, E-mail: [email protected] Welcome to LaborFest 2014 80th Anniversary of San Francisco General Strike and 100th Anniversary of 1914 Ludlow Massacre LaborFest 2014 takes place on the 80th anniversary of core” and testing schemes, all funded by Walmart (Walton the 1934 San Francisco General Strike which included family), the Kipp Foundation (Fischer family, owners of the longshore as well as maritime workers along the entire the GAP), and the Gates Foundation. This is taking place while West Coast. The gains won by the General Strike of ’34 the tech barons are getting tax subsidies while public and are now under attack, including the de- private workers are increasingly squeezed struction of the union hiring hall, the out of the housing market. right to strike and a living wage for all We will also have our annual labor mar- workers. itime boat trip with historian and trade 2014 is also the 100th anniversary of unionists, who will discuss the history of the Ludlow miners’ massacre in Lud- the development of the Bay Area. We will low, Colorado. The mine owner, John tour the newly constructed eastern span D. Rockefeller, ordered gun-wield- of the San Francisco Bay Bridge that was ing company thugs and the Colorado built with 100% union labor. Thirty-three National Guard to burn out and kill 1934 SF General Strike - by Hayden workers died during the building of the the striking miners and their families. -

Historic and Conservation Districts in San Francisco

SAN FRANCISCO PRESERVATION BULLETIN NO. 10 HISTORIC AND CONSERVATION DISTRICTS IN SAN FRANCISCO HISTORIC DISTRICTS -- INTRODUCTION Over the past thirty-five years, the City and County of San Francisco has designated eleven historic districts and six conservation districts and has recognized approximately 30 districts included in the California Register of Historical Resources, the National Register of Historic Places, or named as National Historic Landmark districts. These districts encompass nationally significant areas such as Civic Center and the Presidio National Park; the City’s first commercial center in Jackson Square; warehouse districts such as the Northeast Waterfront and the South End; and residential areas such as Telegraph Hill, Liberty Hill, Alamo Square, Bush Street-Cottage Row and Webster Street. In general, an historic district is a collection of resources (buildings, structures, sites or objects) that are historically, architecturally and/or culturally significant. As an ensemble, resources in an historic district are worthy of protection because of what they collectively tell us about the past. Often, a limited number of architectural styles and types are represented because an historic district is typically developed around a central theme or period of significance. For instance, the theme for a proposed historic district might be “Late 19th century Victorian housing, designed in the Queen Anne style.” Period of significance refers to the span of time during which significant events and activities occurred within the historic district. Events and associations with historic properties are finite; most resources within an historic district have a clearly definable period of significance. A high percentage of buildings located within districts contribute to the understanding of a neighborhood’s or area’s evolution and development through integrity. -

Landmark Designation Work Program HEARING DATE: DECEMBER 15, 2010

Executive Summary Landmark Designation Work Program HEARING DATE: DECEMBER 15, 2010 Date: December 8, 2010 Case No.: 2010.2776 Staff Contact: Mary Brown – (415) 575‐9074 [email protected] Reviewed By: Tim Frye – (415) 575‐6822 [email protected] REQUESTED COMMISSION ACTION This informational presentation to the Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) is intended to inform and guide prioritization of the HPC’s Landmark Designation Work Program (Work Program) for FY2010‐2011. There is no action required at this time. Based on the discussion at the December 15, 2010 hearing, the Planning Department (Department) will return with recommendations at the January 19, 2011 HPC hearing. PROJECT BACKGROUND At its August 4, 2010 hearing the HPC directed Department staff to provide background information on Article 10 Landmark designations to date and identify, if any, trends related to the location, property types, social history, and construction dates of existing Landmarks. While there are no specific Landmark designation criteria outlined in Article 10 of the Planning Code, the HPC was also interested in designations that were made primarily for a property’s association with a significant person, event, or cultural group, rather than solely its architectural qualities. It is the Department’s understanding that the analysis contained in this report will be used to inform and prioritize the HPC’s Landmark Designation Work Program (Work Program) for FY2010‐2011. The budget for this fiscal year allocates one full‐time equivalent (FTE) staff to Landmark designation and other related activities as directed by the HPC. Given the number of eligible resources identified in recent surveys and in past Landmark Preservation Advisory Board work programs, and the workload associated with each designation, staffing for only a limited number of designations is feasible. -

Bay Fill in San Francisco: a History of Change

SDMS DOCID# 1137835 BAY FILL IN SAN FRANCISCO: A HISTORY OF CHANGE A thesis submitted to the faculty of California State University, San Francisco in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Gerald Robert Dow Department of Geography July 1973 Permission is granted for the material in this thesis to be reproduced in part or whole for the purpose of education and/or research. It may not be edited, altered, or otherwise modified, except with the express permission of the author. - ii - - ii - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Maps . vi INTRODUCTION . .1 CHAPTER I: JURISDICTIONAL BOUNDARIES OF SAN FRANCISCO’S TIDELANDS . .4 Definition of Tidelands . .5 Evolution of Tideland Ownership . .5 Federal Land . .5 State Land . .6 City Land . .6 Sale of State Owned Tidelands . .9 Tideland Grants to Railroads . 12 Settlement of Water Lot Claims . 13 San Francisco Loses Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 14 San Francisco Regains Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 15 The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission and the Port of San Francisco . 18 CHAPTER II: YERBA BUENA COVE . 22 Introduction . 22 Yerba Buena, the Beginning of San Francisco . 22 Yerba Buena Cove in 1846 . 26 San Francisco’s First Waterfront . 26 Filling of Yerba Buena Cove Begins . 29 The Board of State Harbor Commissioners and the First Seawall . 33 The New Seawall . 37 The Northward Expansion of San Francisco’s Waterfront . 40 North Beach . 41 Fisherman’s Wharf . 43 Aquatic Park . 45 - iii - Pier 45 . 47 Fort Mason . 48 South Beach . 49 The Southward Extension of the Great Seawall . -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title "Race, Space and Contestation: Gentrification in San Francisco's Latina/o Mission District, 1998-2002 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5c84f2hc Author Casique, Francisco Diaz Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Race, Space, and Contestation: Gentrification in San Francisco’s Latina/o Mission District, 1998-2002 By Francisco Diaz Casique A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Patricia Penn Hilden, Chair Professor José David Saldívar Professor Stephen Small Professor Kim Voss Spring 2013 Abstract “Race, Space, and Contestation: Gentrification in San Francisco’s Latina/o Mission District, 1998-2002” By Francisco Diaz Casique Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Patricia Penn Hilden, Chair From 1995 to 2005, the San Francisco Bay Area underwent quick and rapid changes as the forces of the “New Economy,” particularly those connected to internet related businesses, pushed the region’s economic engine at warp speed. San Francisco power brokers recognized the economic power of these new internet related firms and worked to lure and retain this new economic force to and within the city. By 1998, their efforts, along with other forces, created an uneven spatial distribution of internet related firms in San Francisco’s eastern quadrant, a historically working-class area of the city. The encroachment of these internet related firms into eastern quadrant neighborhoods like the Mission District, a working-class and predominantly Latina/o area of the city, also brought gentrification. -

The Inside Story of the Gold Rush, by Jacques Antoine Moerenhout

The inside story of the gold rush, by Jacques Antoine Moerenhout ... translated and edited from documents in the French archives by Abraham P. Nasatir, in collaboration with George Ezra Dane who wrote the introduction and conclusion Jacques Antoine Moerenhout (From a miniature in oils on ivory, possibly a self-portrait; lent by Mrs. J.A. Rickman, his great-granddaughter.) THE INSIDE STORYTHE GOLD RUSH By JACQUES ANTOINE MOERENHOUT Consul of France at Monterey TRANSLATED AND EDITED FROM DOCUMENTS IN THE FRENCH ARCHIVES BY ABRAHAM P. NASATIR IN COLLABORATION WITH GEORGE EZRA DANE WHO WROTE THE INTRODUCTION AND CONCLUSION SPECIAL PUBLICATION NUMBER EIGHT CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY The inside story of the gold rush, by Jacques Antoine Moerenhout ... translated and edited from documents in the French archives by Abraham P. Nasatir, in collaboration with George Ezra Dane who wrote the introduction and conclusion http://www.loc.gov/resource/ calbk.018 SAN FRANCISCO 1935 Copyright 1935 by California Historical Society Printed by Lawton R. Kennedy, San Francisco I PREFACE THE PUBLICATION COMMlTTEE of the California Historical Society in reprinting that part of the correspondence of Jacques Antoine Moerenhout, which has to do with the conditions in California following the discovery of gold by James Wilson Marshall at Sutter's sawmill at Coloma, January 24, 1848, under the title of “The Inside Story of the Gold Rush,” wishes to acknowledge its debt to Professor Abraham P. Nasatir whose exhaustive researches among French archives brought this hitherto unpublished material to light, and to Mr. George Ezra Dane who labored long and faithfully in preparing it for publication. -

Metreon San Francisco, California

Metreon San Francisco, California Project Type: Commercial/Industrial Case No: C030001 Year: 2000 SUMMARY A 350,000-square-foot urban entertainment center on a 2.75-acre site in downtown San Francisco. Developed by Millenium Partners and WDG Ventures, the project is located within the 87-acre Yerba Buena Center. Within the first few months of its opening in June 1999, Metreon attracted some 2.5 million visitors. As many as 40,000 people have visited on peak-period weekends. The four-level project offers amusements, games, shopping, restaurants, a food court, and cinemas—including a 600-seat SONY•IMAX theater, the largest of its type on the West Coast—enlivening the evening activity of the Yerba Buena Gardens neighborhood. FEATURES Urban entertainment center Downtown development Ground lease Interactive entertainment Metreon San Francisco, California Project Type: Retail/Entertainment Volume 30 Number 01 January-March 2000 Case Number: C030001 PROJECT TYPE A 350,000-square-foot urban entertainment center on a 2.75-acre site in downtown San Francisco. Developed by Millenium Partners and WDG Ventures, the project is located within the 87-acre Yerba Buena Center. Within the first few months of its opening in June 1999, Metreon attracted some 2.5 million visitors. As many as 40,000 people have visited on peak-period weekends. The four-level project offers amusements, games, shopping, restaurants, a food court, and cinemas—including a 600-seat SONY•IMAX theater, the largest of its type on the West Coast—enlivening the evening activity of the Yerba Buena Gardens neighborhood. SPECIAL FEATURES Urban entertainment center Downtown development Ground lease Interactive entertainment DEVELOPER Yerba Buena Retail Partners Millenium Partners 1995 Broadway, 3rd Floor New York, New York 10023 212-595-1600 WDG Ventures 107 Stevenson Street 5th Floor San Francisco, California 94105 415-896-2300 ARCHITECT Simon Martin-Vegue Winkelstein Moris 501 Second Street Suite 701 San Francisco, California 94107 415-546-0400 Gary E. -

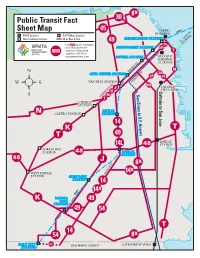

Transit Fact Sheet and Muni Tips With

8x Public Transit Fact 30 Sheet Map 45 FERRY BUILDING BART BART Stations BART/Muni Stations AND AKL GE ID Muni Subway Stations Muni Bus & Rail EMBARCADERO STATION - O F. 49 S. Y BR For route, schedule, 14 BA fare and accessible MONTGOMERY STATION 14x services information T anytime: Call 311 or visit www.sfmta.com POWELL STATION TRANSBAY TERMINAL (AC TRANSIT) N MARKET ST. CIVIC CENTER STATION 30 8x 45 VAN NESS STATION MISSION ST. D x N 14 U CALTRAIN O J R Caltrain to San Jose San to Caltrain 4TH & KING G K ER D SamTrans to S.F. Airport N N U T CHURCH STATION 16TH ST. N CASTRO STATION STATION 14 K T T 49 22ND ST. 14L 48 STATION FOREST HILL STATION 48 24TH ST. STATION 48 J 8x 14x WEST PORTAL MISSION ST. STATION GLEN PARK STATION 14 14x BART BALBOA K PARK 49 STATION 49 54 T 14 54 8x DALY CITY 14L SAN MATEO COUNTY BAYSHORE STATION STATION San Francisco Public Transit Options FACT SHEET AND MUNI ROUTE TIPS Muni bus routes providing alternate, parallel service to BART service within San Francisco are indicated with numbers, while Muni rail lines are indicated with letters. Adult full Muni fare is $2. Youth and Senior/Disabled fare is 75 cents. Exact change or Clipper Cards are required on Muni vehicles; Muni Metro tickets can be purchased at the Metro vend- ing machines in the subway stations for use at subway fare gates. To reach San Francisco International Airport or other peninsula destinations use SamTrans or Caltrain service. -

Conclusions and Recommendations

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS SWEENEY RIDGE THE ROLE OF PORTOLÀ The “Historical Significance of the Discovery of San Francisco Bay” chapter of the Sweeney Ridge section of this study makes the case that Gaspar de Portolá’s discovery of the San Francisco Bay was one of the most important events of California and, in- deed, western history. The find became a central consideration among the Spanish as they began colonization of Alta California. It marked the beginning of the end for the hegemony of the native Californians, who had been here, inhabiting the land without interference, for thousands of years. When one considers the meaningful efforts the National Park Service has expended on the Anza Trail, it becomes a question - - why hasn’t Portolá received this kind of attention? Portolá was first to enter Alta California by land. His expedition resulted in the initiation of the Spanish settlement here. Anza’s exploration was certainly as amazing, considering the hardships of his overland journeys. His trail blazing tried to link Alta California with New Spain. In his second expedition, he took with him the original settlers destined for San Francisco. However, within five years his Anza Trail was closed by the Yuma Indians. Portolá not only already discovered the San Francisco Bay but had additionally helped the Franciscans establish the San Diego and Monterey missions. It seems that his legacy should be as much understood as Anza’s. At Sweeney Ridge the National Park Service possesses the very spot at which the mo- mentous discovery was made. While surrounded by urban growth, the Ridge remains open space and available for a variety of interpretive projects.