Initiating ICT in the Open Distance Learning of Gabonese Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Math Eyes to See Math in Everything We Do

Hosted by the American Institutes for Research Washington Opening Our Math Eyes To See Math In Everything We Do July 12th — July 15th 2015 Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference of Adults Learning Mathematics — A Research Forum (ALM) Edited by Anestine Hector-Mason, Linda Jarlskog and David Kaye AIR is one of the world's largest behavioral and social science research and evaluation organizations. AIR’s mission is to conduct and apply the best behavioral and social science research and evaluation towards improving peoples’ lives, with a special emphasis on the disadvantaged. For more information visit www.air.org. The 22nd Adults Learning enhancement of teaching Mathematics – A Research and learning in higher Forum (ALM) international education Dublin, Ireland conference was hosted by Aspiring through Education the American Institutes for Dr. Roosevelt Johnson, Research (AIR) in Alexandria, Deputy Associate Virginia. The conference showcased Administrator for Education, international perspectives related to the The National Aeronautics teaching and learning of and Space Administration (NASA) Washington, numeracy and mathematics. District of Columbia. International experts in Mathematics in Our Lives numeracy and mathematics Dr. Freeman A. Hrabowski, President, University convened at the conference of Maryland, Baltimore County, Maryland with a focus on five key Numeracy: a Prerequisite for Sustainability discussion topics: Ms. Marilyn Waite, Environmental Sustainability (1) adult numeracy concepts, theories and Engineer; Owner, Sustainable Visit, Paris, France practice; and Beijing, China. (2) science technology engineering and Real-World Problem Solving Through M in STEM mathematics (STEM); Dr. Padmanabhan Seshaiyer, Director, Center for (3) numeracy and diversity; Mathematics Professional Outreach and (4) numeracy and literacy; and Educational Technology, George Mason (5) numeracy and the workforce. -

Reforms of the Gabonese Education System: What Challenges?

RESEARCH ARTICLE Reforms of the Gabonese Education System: What challenges? MBA Eyeghe Jean Paulin1 1Ministry of National Education of Gabon, Gabon *Corresponding author: Ependja Towaka Antoine: [email protected] Abstract: Citation: Mba E. JP (2021) Reforms In the field of education, the idea that an educational system can of Gabonese Education System: What challenges?. Open Science improve is not just an act of faith. Empirical research in social Journal 6(1) sciences and organizational management has shown that such Received: 2nd November 2020 improvement can only be achieved through reforms and their th efficient implementation. However, studies have shown that, in a Accepted: 30 November 2020 similar social context, certain approaches produce opposite nd Published: 22 March 2021 effects. This article presents an overview of the reforms of the Gabonese education system from the 1960s to the present day. It Copyright: © 2021 This is an open access article under the terms of has examined the main administrative acts that have framed the the Creative Commons Attribution content of its reforms, highlighting significant advances in terms License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction of material and social achievements. We noted that the in any medium, provided the Gabonese education system from the 1960s to the 1970s original author and source are credited. increased the schooling of young people to more than 90%. Twenty years later, the system was dysfunctional in terms of a Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work shortage of qualified teachers, classrooms and quality of education. Added to this is the high rate of repetition and school Competing Interests: The author has declared that no competing failure. -

2020 Sustainability and Transparency Report

2020 2020 SUSTAINABILITYSUSTAINABILITY ANDAND TRANSPARENCYTRANSPARENCY REPORTREPORT The terms FSC® and Forest Stewardship The term PEFCTM used herein is a registered Council® used herein are registered trade- trademark of the Program for the Endorse- marks of the Forest Stewardship Council, ment of Forest Certification Schemes Updated version from 18.05.21 A.C. (FSC® C004141). (PEFCTM 15-31-0090). Content Precious Wood's Highlights 2020 4 Our sustainability and transparency report 6 A challenging year 7 Shared value as core of our business 8 Certification as an inherent part of our business ethics 9 Impact on the UN Sustainable Development Goals 10 SOCIAL PERSPECTIVE 12 Our employees - our most important capital 13 Women at Precious Woods 14 Occupational health, safety and training 15 Social responsibility and education 16 Local communities and development 18 Science for sustainability 19 PROJECTS 20 ENVIRONMENTAL PERSPECTIVE 22 Sustainable forest management to protect the forests 23 Wildlife protection 26 Watercourses as a source of life 28 Landscape-level approach to biodiversity conservation 29 Carbon stock, CO2 emission & bioenergy 30 Wildfire monitoring and management 33 Drinking water and water treatment 34 Fuels, chemicals and pest management 35 ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVE 36 Industrial development and cooperation 37 Wood supply and volumes 39 TRANSPARENCY 40 Our business ethics guidelines 41 FPIC, grievance and whistleblowing procedures 42 Procurement and independent suppliers 46 Supply chain and traceability systems 47 Precious Wood's Highlights 2020 20 20 View over our Gabonese forest concession 4 Gabon Visit of the Minister of Forests Prof. Lee White at Precious Woods – CEB 5 Our sustainability and transparency report Not all changes every year, and this is also why you might find several chapters that have not been changed or only slightly adapted from last year’s report. -

30 Years Contributing to Education and Training in Africa Ushirika Wa Maendeleo Ya Elimu Barani Afrika

Ushirika wa Maendeleo ya Elimu Barani Afrika Association for the Development of Education in Africa Association pour le développement de l’éducation en Afrique Associação para o Desenvolvimento da Educação em África 30 Years Contributing to Education and Training in Africa Ushirika wa Maendeleo ya Elimu Barani Afrika Association for the Development of Education in Africa DE A Association pour le développement de l’éducation en Afrique Associação para o Desenvolvimento da Educação em África ADEA’s 30th Anniversary Commemorative Booklet Our Common Voice, Our Common Success. Copyright © 2019 - Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA) ISBN N°13: 978-92-9178-141-6 First edition. All rights reserved. Reproduction and/or distribution is prohibited without the prior consent of ADEA. DE A Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA) African Development Bank Group (AfDB) Immeuble CCIA Plateau, Avenue Jean-Paul II 01 BP 1387 – Abidjan 01 Côte d’Ivoire www.adeanet.org Send feedback to [email protected] Published and distributed by ADEA and Éditions Ganndal (Conakry – Guinée). First print: June 2019. [email protected] www.editionsganndal.blogspot.com A French edition of this booklet, titled “ADEA - 30 Ans de contribution à l’éducation et la formation en Afrique”, is available too. ISBN N°13: 978-92-9178-141-6. Cover design, text design and composition: Stefano De Cupis and Mamy Rijason Razafimahatratra. Proofreading: Shem Okore Bodo, Joel Elegbe Bola, Stefano De Cupis, Aloïse Prosper Faye, Raky Gassama, Youssouf Toure, Aliou Mamadou Sow ADEAnet @ADEAnet ADEA Channel ADEA Photos Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ......................................................................... -

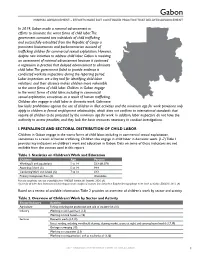

Gabon MINIMAL ADVANCEMENT – EFFORTS MADE but CONTINUED PRACTICE THAT DELAYED ADVANCEMENT

Gabon MINIMAL ADVANCEMENT – EFFORTS MADE BUT CONTINUED PRACTICE THAT DELAYED ADVANCEMENT In 2019, Gabon made a minimal advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. The government convicted two individuals of child trafficking and successfully extradited from the Republic of Congo a prominent businessman and parliamentarian accused of trafficking children for commercial sexual exploitation. However, despite new initiatives to address child labor, Gabon is receiving an assessment of minimal advancement because it continued a regression in practice that delayed advancement to eliminate child labor. The government failed to provide evidence it conducted worksite inspections during the reporting period. Labor inspections are a key tool for identifying child labor violations, and their absence makes children more vulnerable to the worst forms of child labor. Children in Gabon engage in the worst forms of child labor, including in commercial sexual exploitation, sometimes as a result of human trafficking. Children also engage in child labor in domestic work. Gabonese law lacks prohibitions against the use of children in illicit activities and the minimum age for work provisions only apply to children in formal employment relationships, which does not conform to international standards that require all children to be protected by the minimum age for work. In addition, labor inspectors do not have the authority to assess penalties, and they lack the basic resources necessary to conduct investigations. I. PREVALENCE AND SECTORAL DISTRIBUTION OF CHILD LABOR Children in Gabon engage in the worst forms of child labor, including in commercial sexual exploitation, sometimes as a result of human trafficking. Children also engage in child labor in domestic work. -

Access of Girls to Basic Education in Gabon

EDUCATION OF WOMEN IN AFRICA ACCESS OF GIRLS TO BASIC EDUCATION IN GABON Fanta DIALLO MAIGA ACCESS OF GIRLS TO BASIC EDUCATION IN GABON Fanta DIALLO MAIGA UNESCO Regional Office, Dakar The views expressed by the author are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Published by the UNESCO Regional Office in Dakar BP 3311, Dakar, Senegal. ©UNESCO 1994 PREFACE Promoting gender equality and improving the status of women has been a constant concern for UNESCO. The Third Medium Term Plan (1990-1995) lays emphasis on women's participation, considered a sine qua non for sustainable development. Attention is first of all given to education for women and girls, key of their participation, on an equal footing, in all aspects of economic, social and cultural life. In other respects, the fight against physical and moral violence practised on women, the contribution of women in the media and in the safeguard of heritage are as many fields of action in which UNESCO has been steadfastly involved during these past years. These are all the more reasons why UNESCO's Regional Office for Education in Africa (BREDA) is publishing the studies carrier out in the course of its execution of this priority field of action. Most of the Authors are women: African women of different nationalities involved at various levels in the development of their countries. This is already a choice: to give the floor to the academic world, the world of research, the political world in order to make them express an African and "female" point of view. -

Digital Skills for Life and Work September 2017

Working Group on Education: Digital skills for life and work September 2017 Working Group on Education: Digital skills for life and work September 2017 What are the educational implications of the ‘broadband society’ for the development of digital skills for life and work? Foreword by Irina Bokova, UNESCO technologies. So are apps and other tools that facilitate creative expression. But these clicks are not obvious to first time users of technology, and too many people are being excluded from the enrichment opportunities offered by the broadband society. To move forward, we need to tackle complex questions. How can education support the equitable development of digital skills for all? How can we advance digital skills development continually, in the context of fast-changing technologies? In response, this Report by the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development examines how digital skills and competencies The emergence of the digital world is creating can be defined and developed within and vast new opportunities for exchange and beyond formal curricula. It underlines the cooperation. It is also raising sharp questions importance of steadfast commitment to that we must address to advance progress digital skills development for disadvantaged toward the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable groups and the self-evolution of these Development. skills within local communities. It offers recommendations on supporting sustainable People speak of the emergence of a new and equitable development of digital skills for generation of ‘digital natives’ as if this is all stakeholders, showing the catalytic power inevitable. It isn’t — we see new divides of multistakeholder collaboration, the role of emerging and old gaps widening, notably for international cooperation and the importance girls and women. -

Relevance of Deliberative Democratic Evaluation in Secondary Education in Gabon

American Research Journal of Humanities Social Science (ARJHSS)R) 2021 American Research Journal of Humanities Social Science (ARJHSS) E-ISSN: 2378-702X Volume-04, Issue-08, pp-32-37 www.arjhss.com Research Paper Open Access Relevance of deliberative democratic evaluation in secondary education in Gabon. The case of elementary school transformed into colleges Louembet Onguele Christian Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research, Technology Transfer, National Education, in charge of Civic Training, Libreville, Gabon Abstract : The crisis of the Gabonese educational system is current. Efforts to overcome it are multiplying. From the Estates General of 1983 and 2010 to the recent Education Task Force of 2018, there is no shortage of proposals for achieving a quality Gabonese school. In this wake, we see deliberative democratic evaluation in Gabonese secondary education as an essential element in solving the problem. It is an information service for the whole community that is based on inclusion, dialogue, and deliberation. In Gabon's bureaucratized and hyper-centralized education system, the participation of all becomes an emergency in order to be competitive, efficient, and effective. An evaluation that takes into account the diversity of the school's actors is a guarantee of quality. Keywords: Evaluation, democracy, teaching, education, school, Gabon I. Introduction The Gabonese education system was originally governed by Law 16/66 of August 9, 1966. Law 21/2011 of February 14, 2012, which currently guides it, repeals all previous provisions. It is statutorily composed of pre-primary, primary, general and technical secondary, vocational and higher education. Our study concerns general secondary education, in particular the First Cycle, still called Collège, which prepares students for the Brevet d'Enseignement du Premier Cycle exam. -

Quaker Thought and Life Today

Quaker Thought and Life Today VOLUME 9 OCTOBER 15, 1963 NUMBER 20 The Retiring Editor by Mildred Binns Young A.yfomo of "g"go tion based on race, color, or ethnic origin is contrary to the Gospel and is incompati ble with the Christian doctrine Spontaneity in Meeting of man and with the nature by Roliert 0. Blood, Jr. of the church of Christ. When ever and wherever any of us Christians deny this by action or inaction, we betray Christ and the fellowship which bears The Laborers in the Vineyard his name. by Philip H. Miller -from a etatement of the World Council of Churches, 1954 Spiritual Staleness . by Bliss Forbush THIRTY CENTS $5.00 A YEAR Quaker Witness on Capitol Hill 434 FRIENDS JOURNAL October 15, 1963 Quaker Witness on Capitol Hill FRIENDS JOURNAL N ITS almost twenty years of activity, the Friends Committee I on National Legislation has earned a confidence among Congressmen which recently was demonstrated in a statement from Representative Edith Green of Oregon. Commenting about the FCNL Washington Newsletter, Representative Green said: "I know that the material presented is fair and accurate." According to E. Raymond W ilson, the very active "retired" secretary of the FCNL, Friends are given opportunity to pre sent witnesses on Quaker concerns as many as 20 times a year P ublished semimonthly, on the first and fifteenth of each before Congressional Committees. These are some recent FCNL month, at 1515 Cherry Street, Philadelphia 19102, Penn sylvania (LO 3-7669) by Friends Publishing Corporation. witnesses: CARL F. WISE Herbert C. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Quality of This Reproduction Is

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. ÜMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy suhmitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains indistinct, slanted and or light print. All efforts were made to acquire the highest quality manuscript from the author or school. -

A Theoretical Model for a Fang-French-English Specialized Multi-Volume School Dictionary

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository A THEORETICAL MODEL FOR A FANG-FRENCH-ENGLISH SPECIALIZED MULTI-VOLUME SCHOOL DICTIONARY Edgard Maillard Ella Dissertation presented for the Degree of Doctor of Literature (Lexicography) at the University of Stellenbosch Promoter: Prof. R.H Gouws March 2007 DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this dissertation is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirely or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: ………………… Date:………………………. SUMMARY The policy to preserve and implement mother tongues as medium of education in Gabon will lead to the establishing of a bilingual education system. This system will involve mother tongues and French, the official language. In many countries people are nowadays more and more aware of making provision for a multilingual education. In education this has been regarded as the new way and key to development over the last decades. It means that the implementation of a bilingual education system must also include a trilingual vision. Different and new approaches to the role of dictionaries, also in the context in Gabon, lead to diverse areas of particular concern, which are challenging for the metalexicographical research. Accordingly, Part I of the dissertation first presents a comprehensive draft of the structural possibilities of the formulation and compilation of a new type of dictionary. This draft provides for the motivations for the formulation of a Specialized Fang-French- English multi-volume School Dictionary in Gabon, as a type of dictionary, which can fit into the current situation of the national languages and education in Gabon. -

Table of Contents

GABON COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS L. Michael Rives 1961-1963 Director for Central African Countries- State Department, Washington, DC Dorothy E. Eardley 1963-1965 Secretary to the Ambassador, Libreville Robert V. Keeley 1963-1965 Congo-Leopoldville Desk Officer- Central African Affairs, Washington, DC Thompson R. Buchanan 1966-1967 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville John Propst Blane 1966-1969 Desk Officer, State Department, Washington, DC Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1967-1969 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville Richard Funkhouser 1969-1970 Ambassador, Gabon Edward Gibson Lanpher 1969-1971 Political Officer, Libreville Nancy Forbord 1969-1972 Representative to African-American Institute, Libreville Fernando E. Rondon 1970 Madagascar Desk Officer- State Department, Washington, DC Laurent E. Morin 1970 Alternate Country Director- African Bureau, Washington, DC James K. Bishop Jr. 1970-1972 Desk Officer- Central African Affairs, Washington, DC John R. Countryman 1971-1975 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville John A. McKesson, III 1971-1975 Ambassador, Gabon Michael P.E. Hoyt 1972-1974 Rhodesian Desk Officer-State Department, Washington, DC 1 Andrew Steigman 1975-1977 Ambassador, Gabon Arthur T. Tienken 1978-1981 Ambassador, Gabon Francis Terry McNamara 1981-1984 Ambassador, Gabon Herman J. Rossi III 1982-1984 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville Larry C. Williamson 1984-1987 Ambassador, Gabon Ronald K. McMullen 1988-1990 Economic-Commercial Officer, Libreville Keith L. Wauchope 1989-1992 Ambassador, Gabon Joseph C. Wilson, IV 1992-1995 Ambassador, Gabon L. MICHAEL RIVES Director for Central African Countries- State Department Washington, DC (1961-1963) L. Michael Rives was born in New York in 1921. He received a bachelor's degree from Princeton University in 1947 and joined the Foreign Service in 1950.