Differentiating Theists and Nontheists by Way of a Sampling of Self-Reported Sexual Thoughts and Behaviors Kelli Callahan Walden University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jay Bregman Hilary Armstrong Gave the Gnos

NEOPLATONIZING GNOSTICISM AND GNOSTICIZING NEOPLATONISM IN THE “AMERICAN BAROQUE” Jay Bregman Hilary Armstrong gave the Gnostics a fair hearing in his “Dualism: Platonic, Gnostic, and Christian.”1 He basically viewed Gnosticism as having some points of contact with Platonism, but since they were not doing the same thing as philosophers, he reasoned, it would be wrong to treat them as “bad philosophers.” Although Gnostic anti-cosmism is balanced by his nuanced view of certain Gnostic pro-cosmic ideas, Gnostics are “mythicizers,” hence doing something very different from philosophers since, in the last analysis, they think that the cosmos is at best transitory—a place to flee from. However, in the last decade or so, there has been a reconsideration of Armstrong’s view. Led especially by John Turner and others, scholars have affirmed that Gnostics, Middle Platonists, and Neoplatonists indeed have more in common philosophically than had been previously supposed; Gnos- tics were perhaps even writing commentaries on Plato’s dialogues in order to gain a respectable hearing in Plotinus’ seminars.2 Nineteenth-century America was the scene of an earlier engagement with Gnosticism, through which heterodox thinkers paved the way for its current serious reception. I will trace the roots and anticipations of contem- porary discussions, in the Neoplatonic, late Transcendentalist journal, The Platonist, and other North American sources. Metaphysical thinkers of the later American Renaissance painted their religious symbols on a Neoplatonic canvas. A secularizing world had given rise to notions of a universal syncretistic cosmic Theism, which welcomed the “esoteric” strains of all traditions. Alexander Wilder, M.D., a regular con- tributor to The Platonist, also cast a wide syncretistic net: the Neoplatonists taught Platonic philosophy in the form of a religion embracing some of the characteristic features of Jainism, the Sankhya and Pythagorean schools (hē gnōsis tōn ontōn). -

Religion, Institutionalism, Legalism, and Same-Sex Marriage: Comparative Experiences of Non-Heterosexual Males in Northern Ireland and Tennessee

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 5-2019 Religion, institutionalism, legalism, and same-sex marriage: comparative experiences of non-heterosexual males in Northern Ireland and Tennessee Reaghan Gough University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Gough, Reaghan, "Religion, institutionalism, legalism, and same-sex marriage: comparative experiences of non-heterosexual males in Northern Ireland and Tennessee" (2019). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Religion, Institutionalism, Legalism, and Same-Sex Marriage: Comparative Experiences of Non-Heterosexual Males in Northern Ireland and Tennessee by Reaghan Gough Departmental Undergraduate Honors Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Department of Social, Cultural, and Justice Studies (Anthropology) Examination Date: April 2, 2019 Dr. Zibin Guo Dr. Andrew Workinger Professor of Anthropology Professor of Anthropology Thesis Director Department Examiner Gough 1 Table of Contents I. Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 II. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………. 3 III. Anthropological & Historical -

After the Wedding Night: the Confluence of Masculinity and Purity in Married Life Sarah H. Diefendorf a Thesis Submitted in Part

After the Wedding Night: The Confluence of Masculinity and Purity in Married Life Sarah H. Diefendorf A thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2012 Committee: Pepper Schwartz Julie Brines Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Sociology University of Washington Abstract After the Wedding Night: The Confluence of Masculinity and Purity in Married Life Sarah H. Diefendorf Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Pepper Schwartz Department of Sociology Purity is congruent with cultural understandings of femininity, but incongruent with normative definitions of masculinity. Using longitudinal qualitative data, this study analyzes interviews with men who have taken pledges of abstinence pre and post marriage, to better understand the ways in which masculinity is asserted within discourses of purity. Building off of Wilkins’ concept of collective performances of temptation and Luker’s theoretical framing of the “sexual conservative” I argue that repercussions from collective performances of temptation carry over into married life; sex is thought of as something that needs to be controlled both pre and post marriage. Second, because of these repercussions, marriage needs to be re-conceptualized as a “verb”; marriage is not a static event for sexual liberals or sexual conservatives. The current study highlights the ways in which married life is affected by a pledge of abstinence and contributes to the theoretical framing of masculinities as fluid. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank Pepper Schwartz and Julie Brines for their pointed feedback and consistent encouragement and enthusiasm for this research. The author would also like to thank both Aimée Dechter and the participants of the 2011-2012 Masters Thesis Research Seminar for providing the space for many lively, helpful discussions about this work. -

Religion, Homosexuality, and Collisions of Liberty and Equality in American Public Law

A Jurisprudence of "Coming Out": Religion, Homosexuality, and Collisions of Liberty and Equality in American Public Law William N. Eskridge, Jr.! Conflicts among religious and ethnic groups have scored American cultural and political history. Some of these conflicts have involved campaigns of suppression against deviant religious and minority ethnic groups by the mainstream. Although the law has most often been deployed as an instrument of suppression, there is now a public law consensus to preserve and protect the autonomy of religious and ethnic subcultures, as well as the ability of their members to self-identify without penalty. One thesis of this Essay is that this vaunted public law consensus should be extended to sexual orientation minorities as well. Like religion, sexual orientation marks both personal identity and social divisions.' In this century, in fact, sexual orientation has steadily been replacing religion as the identity characteristic that is both physically invisible and morally polarizing. In 1900, one's group identity was largely defined by one's ethnicity, social class, sex, and religion. The norm was Anglo-Saxon, middle-class, male, and Protestant. The Jew, Roman Catholic, or Jehovah's Witness was considered deviant and was subject to social, economic, and political discrimination. In 2000, one's group identity will be largely defined by one's race, income, sex, and sexual orientation. The norm will be white, middle-income, male, and heterosexual. The lesbian, gay man, or transgendered person will be considered deviant and will be subject to social, economic, and political discrimination. t Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. An earlier draft of this Essay was presented at workshops held at the Georgetown University Law Center. -

Syllabus Sexuality and Religion REL 3171 RVC 1181 GENERAL

Syllabus Sexuality and Religion REL 3171 RVC 1181 GENERAL INFORMATION PROFESSOR INFORMATION Instructor: Stephanie Londono Phone: (305) 348-0000 Office: Office Office Hours: By Appointment E-mail: [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION AND PURPOSE Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth— for your love is more delightful than wine. 3 Pleasing is the fragrance of your perfumes; your name is like perfume poured out. No wonder the young women love you! 4 Take me away with you—let us hurry! Let the king bring me into his chambers. Solomon’s songs of Songs (1:2-4) Sexuality and religion have always been intimately connected. Even in our secularized western societies, the dominant views about reproduction, gender, desire, love, power, purity, celibacy, and identity are directly informed by religion. To be sure, today’s most fervent political and cultural debates such as abortion, contraception, same-sex marriage, transgender rights, pedophilia, and, most recently, sexual victimization lie within the perimeters of perhaps the ultimate taboo: religion and sexuality. Interestingly, whether the sacredness of religion is appropriated to approach sexuality in a beneficial or detrimental way, these two topics will forever intersect –sometimes in palpable ways, but also in ambiguous and unexpected manners. The interest of this course is to provide a safe and broad platform to critically discuss the complex and fluid intersections between sexuality and religion. We will address urgent and perennial questions from different religious perspectives, such as what is the spiritual meaning of sexuality? Is sexuality an obstacle or a vehicle for spiritual fulfillment? Who are the voices of authority who set the sacred rules on sexuality and who gets to enforce them? In this ambitious and interdisciplinary overview, we will analyze the intricate ways in which religion and sexuality have influenced each other over the last half century; and the variety of challenges that contemporary sexual practice and research pose to traditional religions. -

Statement of the Problem 1

Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary THE INCOMPATIBILITY OF OPEN THEISM WITH THE DOCTRINE OF INERRANCY A Report Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Theology by Stuart M. Mattfield 29 December 2014 Copyright © 2015 by Stuart M. Mattfield All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As with all things, the first-fruits of my praise goes to God: Father, Son and Spirit. I pray this work brings Him glory and honor. To my love and wife, Heidi Ann: You have been my calm, my sanity, my helpful critic, and my biggest support. Thank you and I love you. To my kids: Madison, Samantha, and Nick: Thank you for your patience, your humor, and your love. Thank you to Dr. Kevin King and Dr. Dan Mitchell. I greatly appreciate your mentorship and patience through this process. iii ABSTRACT The primary purpose of this thesis is to show that the doctrine of open theism denies the doctrine of inerrancy. Specifically open theism falsely interprets Scriptural references to God’s Divine omniscience and sovereignty, and conversely ignores the weighty Scriptural references to those two attributes which attribute perfection and completeness in a manner which open theism explicitly denies. While the doctrine of inerrancy has been hotly debated since the Enlightenment, and mostly so through the modern and postmodern eras, it may be argued that there has been a traditional understanding of the Bible’s inerrancy that is drawn from Scripture, and has been held since the early church fathers up to today’s conservative theologians. This view was codified in October, 1978 in the form of the Chicago Statement of Biblical Inerrancy. -

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene's 'Dark and Magical Heart

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ by Dorcas Wangui MA (Lancaster) BA (Lancaster) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 Wangui 1 Abstract Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ This study explores the ways in which Catholic images, statues, and icons haunt the fictional, spiritual wasteland of Greene’s writing, nicknamed ‘Greeneland’. It is also prompted by a real space, discovered by Greene during his 1938 trip to Mexico, which was subsequently fictionalised in The Power and the Glory (1940), and which he described as ‘a short cut to the dark and magical heart of faith’. This is a space in which modern notions of disenchantment meets a primal need for magic – or the miraculous – and where the presentation of concepts like ‘salvation’ are defamiliarised as savage processes that test humanity. This brutal nature of faith is reflected in the pagan aesthetics of Greeneland which focus on the macabre and heretical images of Christianity and how for Greene, these images magically transform the darkness of doubt into desperate redemption. As an amateur spy, playwright and screen writer Greene’s visual imagination was a strength to his work and this study will focus on how the visuality of Greene’s faith remains in dialogue with debates concerning the ‘liquidation of religion’ in society, as presented by Graham Ward. The thesis places Greene’s work in dialogue with other Catholic novelists and filmmakers, particularly in relation to their own visual-religious aesthetics, such as Martin Scorsese and David Lodge. -

Response to Papers on Theism (Just a Little) and Non-Theism (Much More)

Quaker Religious Thought Volume 118 Article 6 1-1-2012 Response to Papers on Theism (Just a Little) and Non-Theism (Much More) Patrick J. Nugent Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Nugent, Patrick J. (2012) "Response to Papers on Theism (Just a Little) and Non-Theism (Much More)," Quaker Religious Thought: Vol. 118 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt/vol118/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Religious Thought by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESPONSE TO PAPERS ON THEISM (JUST A LITTLE) AND NON-THEISM (MUCH MORE) Patrick J. nuGent am immensely grateful for the opportunity to respond to these I two papers and regret that I cannot be present. I am going to trust that Jeffrey Dudiak’s excellent and thought-provoking paper will inspire good conversation in San Francisco, and I wish take up the opportunity offered by David Boulton’s. I share Jeff’s position as a Christ-centered and theistic Friend, and I regret that he chose not to be more of an apologist for Quaker theism in his fine paper. My position remains that a thorough, contextual, and systematic reading of the Quaker authors of the first one hundred fifty years cannot sustain non-theism as authentically Quaker. Yet I would rather respond constructively to David’s paper as a theological colleague responding to an emerging theology that raises fertile theological opportunities to attain the mature theological credibility non-theism does not yet have. -

The Vedanta of Ramanuja

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Philosophy & Comparative Religion Department Faculty Publications Philosophy & Comparative Religion Department 2016 Review of Indian Thought and Western Theism: The Vedanta of Ramanuja Sucharita Adluri Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clphil_facpub Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Hindu Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Original Citation Adluri, S. (2016). Review of Martin Ganeri's Indian Thought and Western Theism: The Vedanta of Ramanuja, Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies, 29, 77-9. This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy & Comparative Religion Department at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy & Comparative Religion Department Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 29 God and Evil in Hindu and Christian Article 14 Theology, Myth, and Practice 2016 Book Review: Indian Thought and Western Theism: the Vedan̄ ta of Ram̄ an̄ uja Sucharita Adluri Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Hindu Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Adluri, Sucharita (2016) "Book Review: Indian Thought and Western Theism: the Vedan̄ ta of Ram̄ an̄ uja," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 29, Article 14. -

Open Theism and Pentecostalism: a Comparative Study of the Godhead, Soteriology, Eschatology and Providence

OPEN THEISM AND PENTECOSTALISM: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE GODHEAD, SOTERIOLOGY, ESCHATOLOGY AND PROVIDENCE By RICHARD ALLAN A Thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Despite Open Theism’s claims for a robust ‘Social’ Trinitarianism, there exists significant inconsistencies in how it is portrayed and subsequently applied within its wider theology. This sympathetic, yet critical, evaluation arises from the Pneumatological lacuna which exists not only in the conception of God as Trinity, but the subsequent treatment of divine providence, soteriology and eschatology. In overcoming this significant lacuna, the thesis adopts Francis Clooney’s comparative methodology as a means of initiating a comparative dialogue with Pentecostalism, to glean important insights concerning its Pneumatology. By engaging in the comparative dialogue between to the two communities, the novel insights regarding the Spirit are then incorporated into a provisional and experimental model of Open Theism entitled Realizing Eschatology. -

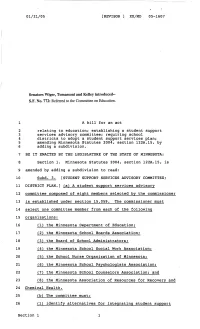

1 a Bill for an .Act 05-1607 2 Relating to Education

01/21/05 [REVISOR ] XX/MD 05-1607 Senators Wiger, Tomassoni and Kelley introduced- S.F. No. 772: Referred to the Committee on Education. 1 A bill for an .act 2 relating to education; establishing a student support 3 services advisory committee; requiring school 4 districts to adopt a student support services plan; 5 amending Minnesota Statutes 2004, section 122A.15, by 6 adding a subdivision. 7 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF MINNESOTA: 8 Section 1. Minnesota Statutes 2004, section 122A.15, is 9 amended by adding a subdivision to read: 10 Subd. 3. [STUDENT SUPPORT SERVICES ADVISORY COMMITTEE; 11 DISTRICT PLAN.] (a) A student support services advisory 12 committee composed of eight members selected by .the commissioner 13 is established under section 15.059. The commissioner must 14 select one committee member from each of the following 15 organizations: 16 (1) the Minnesota Department of Education; 17 (2) the Minnesota School Boards Association; 18 (3) the Board of School Administrators; 19 (4) the Minnesota School Social Work Association; 20 (5) the School Nurse Organization of Minnesota; 21 (6) the Minnesota School Psychologists Association; 22 (7) the Minnesota School Counselors Association; and 23 (8) the Minnesota Association of Resources for Recovery and 24 Chemical Health. 25 (b) The committee must: 26 (1) identify alternatives for integrating student support Section 1 1 01/21/05 [REVISOR ] XX/MD 05-1607 1 services into public schools; 2 (2) recommend support staff to student ratios and best 3 practices for providing student support services premised on 4 valid, widely recognized research; 5 (3) identify the substance and extent of the work that 6 . -

CROSSLING, LOVE L., Ph.D. Abstinence Curriculum in Black Churches: a Critical Examination of the Intersectionality of Race, Gender, and SES

CROSSLING, LOVE L., Ph.D. Abstinence Curriculum in Black Churches: A Critical Examination of the Intersectionality of Race, Gender, and SES. (2009) Directed by Dr. Kathleen Casey. 243 pp. Current sex education curriculum focuses on pregnancy and disease, but very little of the curriculum addresses the social, emotional, or moral elements. Christian churches have made strides over the last two decades to design an abstinence curriculum that contains a moral strand, which addresses spiritual, mental, social, and emotional challenges of premarital sex for youth and singles. However, many black churches appear to be challenged in four areas: existence, purpose, developmental process, and content of teaching tools at it relates to abstinence curriculum. Existence refers to whether or not a church body deems it necessary or has the available resources to implement an abstinence curriculum. Purpose refers to the overall goals and motivations used to persuade youth and singles. Developmental process describes communicative power dynamics that influence the recognized voices at the decision-making table when designing a curriculum. Finally, content of teaching tools refers to prevailing white middle class messages found in Christian inspirational abstinence texts whose cultural irrelevance creates a barrier in what should be a relevant message for any population. The first component of the research answers the question of why the focus should be black churches by exploring historical and contemporary distinctions of black sexuality among youth and single populations. The historical and contemporary distinctions are followed by an exploration of how the history of black church development influenced power dynamics, which in turn affects the freedom with which black Christian communities communicate about sexuality in the church setting.