Samuel Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary Jones: Last First Lady of the Republic of Texas

MARY JONES: LAST FIRST LADY OF THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS Birney Mark Fish, B.A., M.Div. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2011 APPROVED: Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Major Professor Richard B. McCaslin, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History D. Harland Hagler, Committee Member Denis Paz, Committee Member Sandra L. Spencer, Committee Member and Director of the Women’s Studies Program James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Fish, Birney Mark. Mary Jones: Last First Lady of the Republic of Texas. Doctor of Philosophy (History), December 2011, 275 pp., 3 tables, 2 illustrations, bibliography, 327 titles. This dissertation uses archival and interpretive methods to examine the life and contributions of Mary Smith McCrory Jones in Texas. Specifically, this project investigates the ways in which Mary Jones emerged into the public sphere, utilized myth and memory, and managed her life as a widow. Each of these larger areas is examined in relation to historiographicaly accepted patterns and in the larger context of women in Texas, the South, and the nation during this period. Mary Jones, 1819-1907, experienced many of the key early periods in Anglo Texas history. The research traces her family’s immigration to Austin’s Colony and their early years under Mexican sovereignty. The Texas Revolution resulted in her move to Houston and her first brief marriage. Following the death of her husband she met and married Anson Jones, a physician who served in public posts throughout the period of the Texas Republic. Over time Anson was politically and personally rejected to the point that he committed suicide. -

Eastman Notes July 2006

“Serving a Great and Noble Art” Eastman Historian Vincent Lenti surveys the Howard Hanson years E-Musicians Unite! Entrepreneurship, ESM style Tony Arnold Hitting high notes in new music Summer 2009 FOr ALUMNI, PARENTS, AND FrIeNDS OF THe eASTmAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC FROM THE DEAN The Teaching Artist I suppose that in the broadest sense, art may be one of our greatest teachers. Be it a Bach Goldberg Variation, the brilliant economy of Britten’s or- chestration in Turn of the Screw, the music in the mad ruminations of King Lear, or the visual music of Miro, it is the stirring nature of such intense, insightful observation that moves us. Interestingly, these artistic epiphanies bear a remarkable resemblance to what happens during great teaching. And I believe that some of the many achieve- ments of Eastman alumni, faculty and students can be traced to great Eastman “teaching moments.” Like great art, great teaching is not merely the efficient transmission of knowl- NOTES edge or information, but rather a process by which music Volume 27, Number 2 or information gets illuminated by an especially insight- Summer 2009 ful light, thus firing our curiosity and imagination. Great teachers, like great artists, possess that “special light.” Editor It’s hard to define what constitutes good teaching. In David Raymond the academic world, we try to quantify it, for purposes Contributing writers of measurement, so we design teaching evaluations that Lisa Jennings Douglas Lowry hopefully measure the quality of the experience. Yet Helene Snihur when each of us is asked to describe our great teachers, Contributing photographers we end up being confounded, indeed fascinated, by the Richard Baker dominant intangibles; like music or other art, the price- Steve Boerner less stirring aspects we just can’t “explain.” Kurt Brownell Great music inspires us differently, depending on tem- Gary Geer Douglas Lowry Gelfand-Piper Photography perament, musical and intellectual inclinations, moods, Kate Melton backgrounds, circumstances and upbringings. -

Appalachian Spring: Ballet for Orchestra 8 Aaron Sherber

Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 33 2017 15 E. Market Street, #22 Leesburg, VA 20178 Phone: (202) 643-4791 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.conductorsguild.org Officers John Farrer, President John Ross, Treasurer Christopher Blair, Vice President David Leibowitz, Secretary Julius Williams, President-Elect Gordon Johnson, Past President Board of Directors Marc-André Bougie Claire Fox Hillard Dominique Røyem Wesley J. Broadnax Silas Nathaniel Huff Jeffrey Schindler Jonathan Caldwell David Itkin Markand Thakar Rubén Capriles Geneviève LeClair Robert Whalen Peter Cokkinias Paul Manz Mark Crim Jon C. Mitchell Atty. Ira Abrams, Counsel to the Board Jan Wilson*, Executive Director Nathaniel F. Parker*, Editor, Journal of the Conductors Guild *Ex-officio Advisory Council James Allen Anderson Michael Griffith Harlan D. Parker Pierre Boulez** Gordon Johnson Donald Portnoy Emily Freeman Brown Samuel Jones Barbara Schubert Michael Charry Tonu Kalam Gunther Schuller** Sandra Dackow Wes Kenney Leonard Slatkin Harold Farberman Daniel Lewis** Adrian Gnam Larry Newland Max Rudolf Award Winners Herbert Blomstedt Gustav Meier** Jonathan Sternberg David M. Epstein Otto-Werner Mueller** Paul Vermel Donald Hunsberger Helmuth Rilling Daniel Lewis** Gunther Schuller** Thelma A. Robinson Award Winners Beatrice Jona Affron Katherine Kilburn Annunziata Tomaro Eric Bell Matilda Hofman Robert Whalen Miriam Burns Octavio Más-Arocas Steven Martyn Zike Kevin Geraldi Jamie Reeves Carolyn Kuan Laura Rexroth Theodore Thomas Award Winners Claudio Abbado** Frederick Fennell** Robert Shaw** Maurice Abravanel** Bernard Haitink Leonard Slatkin Marin Alsop Margaret Hillis** Esa-Pekka Salonen Leon Barzin** James Levine Sir Georg Solti** Leonard Bernstein** Kurt Masur** Michael Tilson Thomas Pierre Boulez** Sir Simon Rattle David Zinman Sir Colin Davis** Max Rudolf** **In Memoriam Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 33 (2017) Nathaniel F. -

Marisa Mccarthy [email protected] (626) 793-7172 Ext

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Pasadena Symphony Association Pasadena Symphony & POPS Contact: Marisa McCarthy [email protected] (626) 793-7172 ext. 13 For artist bios and images visit: http://pasadenasymphony-pops.org/2018-19-classics- announcement/ February 20, 2018 PASADENA SYMPHONY ANNOUNCES 2018-19 CLASSICS SEASON Guest artists include celebrated violinist Anne Akiko Meyers, Van Cliburn winner Olga Kern, Sphinx Competition winner Melissa White and Baroque concertos featuring the orchestra’s principal musicians. Pasadena, CA – The Pasadena Symphony announces its 91st season with a larger than life schedule of seven concerts, commencing on October 20th with Mozart’s Requiem through to a May 4th finale with the four most famous notes in Classical music – Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Other highlights include Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 “Titan,” a tribute to the great Leonard Bernstein and a Tchaikovsky Spectacular for the ages. All concerts take place at Pasadena’s historic Ambassador Auditorium with performances at both 2pm and 8pm. The season also includes the annually sold out Holiday Candlelight Concert, newly lead by Music Director David Lockington, on Saturday, December 15, 2018 with both 4pm and 7pm performances at All Saints Church. The Pasadena Symphony Association is pleased to announce this upcoming season after recently signing a new five-year musician’s contract, reinforcing its position as the area’s premiere destination for live symphonic music with an eye for long-term stability and artistic growth. Music Director David Lockington kicks off the 2018-19 season on October 20, 2018 with Mozart’s hauntingly beautiful Requiem. On November 17th he celebrates three of America’s greatest composers with masterpieces from On the Town to West Side Story from Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland and Samuel Barber with Sphinx Competition Laureate -violinist Melissa White. -

Ulysses Kay (19 I 7 -1995) Joys and Fears Street Wanderings

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Printed Performance Programs (PDF Format) Music Performances 3-21-1998 Chapman University Chamber Orchestra Chapman University Chamber Orchestra Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/music_programs Recommended Citation Chapman University Chamber Orchestra, "Chapman University Chamber Orchestra" (1998). Printed Performance Programs (PDF Format). Paper 138. http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/music_programs/138 This Other Concert or Performance is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Performances at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Printed Performance Programs (PDF Format) by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY School of Music presents the Chapman University Chamber Orchestra 27th Season John Koshak Music Director and Conductor Saturday, March Z 1st, 1998 Salmon Recital Hall 8:00 PM Program Sounds of My Country Alen C. Agadzhanyan (b. 1976) In Retrospect Samuel ]ones (b. 1935) The Quiet One (Suite from the Film Score) Ulysses Kay (19 I 7 -1995) Joys and Fears Street Wanderings . Interlude Crisis Intermission Symphony #1 Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Adagio: Allegro vivace Andante Menuetto Allegro vivace Ushers Provided by Chapman Music Associates and Delta Omicron, Gamma Tau Chapter Program Notes SAMUEL JONES Samuel Jones received his undergraduate degree with highest honors at Millsays College and his professional training at the Eastman School o Music, where he earned his M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in composition under Howard Hanson, Bernard Rogers, and Wayne Barlow. A former conducting student of Richard Lert and William Steinberg, he served for eight years as a conductor of the Rochester Philharmonic, as well as earlier tenures as conductor of the Saginaw Symphony, music advisor of the Flint Symphony, and founder of the Alma Syml'hony. -

Stanley Hasty: His Life and Teaching Elizabeth Marie Gunlogson

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Stanley Hasty: His Life and Teaching Elizabeth Marie Gunlogson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC STANLEY HASTY: HIS LIFE AND TEACHING By ELIZABETH MARIE GUNLOGSON A treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2006 Copyright @ 2006 Elizabeth M. Gunlogson All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Treatise of Elizabeth M. Gunlogson defended on November 10, 2006. ______________________ Frank Kowalsky Professor Directing Treatise ______________________ Seth Beckman Outside Committee Member ______________________ Patrick Meighan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Stanley and June Hasty iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Stanley and June Hasty for sharing their life story with me. Your laughter, hospitality and patience throughout this whole process was invaluable. To former Hasty students David Bellman, Larry Combs, Frank Kowalsky, Elsa Ludewig- Verdehr, Tom Martin and Maurita Murphy Mead, thank you for your support of this project and your willingness to graciously share your experiences with me. Through you, the Hasty legacy lives on. A special thanks to the following people who provided me with valuable information and technical support: David Coppen, Special Collections Librarian and Archivist, Sibley Music Library (Eastman School of Music); Elizabeth Schaff, Archivist, Peabody Institute/Baltimore Symphony Orchestra; Nicole Cerrillos, Public Relations Manager, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra; Tom Akins, Archivist, Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra; James Gholson, Professor of Clarinet, University of Memphis; Carl Fischer Music Publishing; and Annie Veblen-McCarty. -

American Board of Family Medicine Elects New Officers and Board

J Am Board Fam Med: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.120167 on 5 September 2012. Downloaded from BOARD NEWS American Board of Family Medicine Elects New Officers and Board Members Jane Ireland The American Board of Family Medicine addition to serving as the secretary/treasurer for (ABFM) is pleased to announce the election of 4 its Board of Directors. He is also the program new officers and 4 new board members. The new director and a member of the teaching faculty of officers elected at the ABFM’s spring board the Virginia Commonwealth University Fairfax meeting in April are Samuel Jones, MD, of Fair- Family Medicine Residency Program. Dr. Jones fax, Virginia, elected as Chair; Diane K. Beebe, will serve the ABFM on the Executive Commit- MD, of Jackson, Mississippi, as Chair Elect; Mi- tee as its chair. chael G. Workings, MD, of Detroit, Michigan, as Treasurer; and Erika Bliss, MD, of Seattle, Washington, as Member-at-Large, Executive Committee. The new ABFM officers will each serve a 1-year term. In addition, the ABFM welcomes this year’s new members to the Board of Directors: Christine C. Matson, MD, of Norfolk, Virginia; David W. Mer- copyright. cer, MD, of Omaha, Nebraska; Marcia J. Nielsen, PhD, MPH, of Lawrence, Kansas; and Keith L. Stelter, MD, of Mankato, Minnesota. Diane K. Beebe, MD, Chair-Elect,isthe http://www.jabfm.org/ chairman of the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. She previously served as the residency director and vice-chairman for the Department of Family Med- icine. -

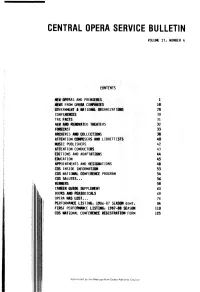

Central Opera Service Bulletin Volume 27, Number 4

CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE BULLETIN VOLUME 27, NUMBER 4 CONTENTS NEK OPERAS AND PREMIERES 1 NEWS FROM OPERA COMPANIES 18 GOVERNMENT ft NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS 28 CONFERENCES 30 TAX FACTS 31 NEtf AND RENOVATED THEATERS 32 FORECAST 33 ARCHIVES AND COLLECTIONS 38 ATTENTION COMPOSERS AND LIBRETTISTS 40 MUSIC PUBLISHERS 42 ATTENTION CONDUCTORS 43 EDITIONS AND ADAPTATIONS 44 EOUCATION 45 APPOINTMENTS AND RESIGNATIONS 48 COS INSIDE INFORMATION 53 COS NATIONAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM 54 COS SALUTES... 56 WINNERS 58 CAREER GUIDE SUPPLEMENT 60 BOOKS AND PERIODICALS 68 OPERA HAS LOST... 76 PERFORMANCE LISTING, 1986-87 SEASON CONT. 84 FIRST PERFORMANCE LISTING. 1987-88 SEASON 110 COS NATIONAL CONFERENCE REGISTRATION FORM 125 Sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera National Council !>i>'i'h I it •'••'i1'. • I [! I • ' !lIN., i j f r f, I ;H ,',iK',"! " ', :\\i 1 ." Mi!', ! . ''Iii " ii1 ]• il. ;, [. i .1; inil ' ii\ 1 {''i i I fj i i i11 ,• ; ' ; i ii •> i i«i ;i •: III ,''. •,•!*.', V " ,>{',. ,'| ',|i,\l , I i : I! if-11., I ! '.i ' t*M hlfi •'ir, S'1 , M"-'1'1" ' (.'M " ''! Wl • ' ;,, t Mr '«• I i !> ,n 'I',''!1*! ,1 : I •i . H)-i -Jin ' vt - j'i Hi I !<! :il --iiiAi hi CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE BULLETIN Volume 27, Number 4 Spring/Summer 1987 CONTENTS New Operas and Premieres 1 News from Opera Companies 18 Government & National Organizations 28 Conferences 30 Tax Facts 31 New and Renovated Theaters 32 Forecast 33 Archives and Collections 38 Attention Composers and Librettists 40 Music Publishers 42 Attention Conductors 43 Editions and Adaptations 44 Education 45 Appointments and Resignations 48 COS Inside Information 53 COS National Conference Program 54 COS Salutes.. -

Benjamin, Sallie, and the Shepherd School of Music by Anne Schnoebelen Joseph and Idea Kirkland Mullen Emerita Professor of Music

The Cornerstone WINTER/SPRING 2007 THE NEWSLETTER OF THE RICE HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOL. 11, NO. 3 Benjamin, Sallie, and the Shepherd School of Music By Anne Schnoebelen Joseph and Idea Kirkland Mullen Emerita Professor of Music Those who thrill to the splendid concerts and “When I was a tiny tot there is a tradition recitals presented by faculty and students of that I ran and got Grandfather Shepherd my the Shepherd School of Music might baby pillow as I saw him dozing in the wonder about its name, origins and early chair. It is a gratifying thought that I history before it became one of the could do something for him who jewels in Rice’s crown. Due to the bestowed so many benefits on me.And munificence of the Shepherd family, of on this same visit to us at Palmya, which Benjamin A. Shepherd was the Virginia, I played for him on my toy patriarch, and the desire of his musical piano. He is said to have remarked, granddaughter Sallie Shepherd Perkins ‘that child has got to go to Leipsic!’” to honor him, Rice University now has (No doubt his reference was to Leipzig’s one of the leading music schools in the famous Hochschule fur Musik founded nation. by Mendelssohn in 1843, one of the Benjamin Armistead Shepherd, according leading music conservatories of the late 19th to a document titled “The Transplanted century.) Virginian” written by Sallie Shepherd Sallie Shepherd Perkins, 1940 Sallie, however, did not go to Perkins, was born May 14, 1814 at Leipzig, but did graduate in music from “Laughton,” Fluvanna County,Virginia. -

JACKSONVILLE SYMPHONY CELEBRATES AMERICAN COMPOSERS in AMERICAN LANDSCAPES the Music of Barber, Bernstein, Ellington, Hanson & Liebermann

JACKSONVILLE SYMPHONY CELEBRATES AMERICAN COMPOSERS IN AMERICAN LANDSCAPES The music of Barber, Bernstein, Ellington, Hanson & Liebermann Jacksonville, FL (May 9, 2018) --- The Jacksonville Symphony will present a program celebrating American composers on May 18-20. The program is titled American Landscapes and features works by Samuel Barber, Leonard Bernstein, Duke Ellington, Lowell Liebermann and Howard Hanson. WHO: Leading this program of American works is American conductor Kazem Abdullah. A vibrant, versatile and compelling presence on the podium, Abdullah is one of the most watched talents on the international stage today. Since 2012 he has been Generalmusikdirektor of the City of Aachen, Germany, where he leads both the orchestral and operatic seasons. Recently, he was nominated by critics in Die Welt, as best conductor in the state of Nordrhein-Westfalen for his conducting of Brokeback Mountain, Tosca and Tannhäuser. In 2009, Abdullah conducted a 12 city tour of the United States with Orquestra de São Paulo, one of Brazil’s most celebrated ensembles. Internationally he has made appearances with ensembles including the St. Gallen Symphony Orchestra, New World Symphony, the Boca del Rio Philharmonic and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Born in the United States, Abdullah began his musical studies at the age of 10. A graduate of the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music with a Bachelor of Music in clarinet performance, he continued his studies at the University of Southern California. In 2006 Abdullah was appointed assistant conductor at the Metropolitan Opera in New York by Music Director James Levine. Abdullah made his Metropolitan Opera debut conducting Gluck’s Orfeo ed Eurydice. -

(1846–1920). Russian Jeweller, of French Descent. He Achieved Fame

Fabricius ab Aquapendente, Hieronymus (Geronimo Fabrizi) (1533–1619). Italian physician, born at Aquapendente, near Orvieto. He studied medicine under *Fallopio at Padua and succeeded F him as professor of surgery and anatomy 1562– 1613. He became actively involved in building Fabergé, Peter Carl (1846–1920). Russian jeweller, the university’s magnificent anatomical theatre, of French descent. He achieved fame by the ingenuity which is preserved today. He acquired fame as a and extravagance of the jewelled objects (especially practising physician and surgeon, and made extensive Easter eggs) he devised for the Russian nobility and contributions to many fields of physiology and the tsar in an age of ostentatious extravagance which medicine, through his energetic skills in dissection ended on the outbreak of World War I. He died in and experimentation. He wrote works on surgery, Switzerland. discussing treatments for different sorts of wounds, and a major series of embryological studies, illustrated Fabius, Laurent (1946– ). French socialist politician. by detailed engravings. His work on the formation of He was Deputy 1978–81, 1986– , Minister for the foetus was especially important for its discussion Industry and Research 1983–84, Premier of France of the provisions made by nature for the necessities 1984–86, Minister of Economics 2000–02 and of the foetus during its intra-uterine life. The medical Foreign Minister 2012–16, and President of the theory he offered to explain the development of eggs Constitutional Council 2016– . and foetuses, however, was in the tradition of *Galen. Fabricius is best remembered for his detailed studies Fabius Maximus Verrocosus Cunctator, Quintus of the valves of the veins. -

'The Beauty Is . . .'

CONVERSATION EVENTS Eastman Loves Lenny Mark Watters Walker 95, Adler 90 EASTMAN NOTESFALL 2018 ‘The Beauty Is . .’ Eastman Opera Theatre’s The Light in the Piazza ONE. MANY. MELIORA WEEKEND OCTOBER 4–7 • 2018 • ALL. You live ever better, every day, creating a ripple of positive change wherever MELIORA WEEKEND you go. This fall, bring it home for our 18th celebration with classmates and OCTOBER 4–7, 2018 the entire Rochester family. Get back to the very best of your University roots, across the River Campus and Medical Center, to the Eastman School of Music Don’t miss the festivities! and Memorial Art Gallery. Register today at rochester.edu/melioraweekend CELEBRATE, RECONNECT, AND RENEW YOUR SPIRIT OF MELIORA. Featuring Soledad O’Brien, Michael Steele, Ron Chernow, Nasim Pedrad, Pink Martini and more! { FALL 2018 } Marian McPartland supported (and frequently performed with) Eastman faculty members and students. Here she is shown with Jeremy Siskind ’08E in 2006. Jeremy has gone 2 on to a great career of his own. From the Dean 3 Brief Notes 6 “The Beauty Is . .” Eastman Opera Theatre lights up Kodak Hall. 4 Alumni on the Move 10 Facing Challenges and 26 Dreaming Dreams School News Thoughts on a musical life from our new faculty members. 32 Recordings All the Things 16 Walker 95, Adler 90 35 Tributes to two great Eastman, and American, Alumni Notes 12 composers. She Was 37 Dazzling pianist, total musician, 18 Eastman Loves Lenny Tributes caring mentor, and a woman with The American maestro had some early and 40 a very full vocabulary: Eastman unexpected ties to Eastman.