Dr. Seuss & WWII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beloved Holiday Movie: How the Grinch Stole Christmas! 12/9

RIVERCREST PREPARATORY ONLINE SCHOOL S P E C I A L I T E M S O F The River Current INTEREST VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3 DECEMBER 16, 2014 We had our picture day on Beloved Holiday Movie: How the Grinch Stole Christmas! 12/9. If you missed it, there will be another opportunity in the spring. Boris Karloff, the voice of the narrator and the Grinch in the Reserve your cartoon, was a famous actor yearbook. known for his roles in horror films. In fact, the image most of us hold in our minds of Franken- stein’s monster is actually Boris Karloff in full make up. Boris Karloff Jan. 12th – Who doesn’t love the Grinch Winter Break is Is the reason the Grinch is so despite his grinchy ways? The Dec. 19th popular because the characters animated classic, first shown in are lovable? We can’t help but 1966, has remained popular with All class work must adore Max, the unwilling helper of children and adults. be completed by the Grinch. Little Cindy Lou Who The story, written by Dr. Seuss, the 18th! is so sweet when she questions was published in 1957. At that the Grinch’s actions. But when the I N S I D E time, it was also published in Grinch’s heart grows three sizes, THIS ISSUE: Redbook magazine. It proved so Each shoe weighed 11 pounds we cheer in our own hearts and popular that a famous producer, and the make up took hours to sing right along with the Whos Sports 2 Chuck Jones, decided to make get just right. -

SEUSSICAL This December, W.F. West Theatre Continues Its Tradition

SEUSSICAL This December, W.F. West Theatre continues its tradition of bringing children’s theatre to our community when we present: Seussical. The amazing world of Dr. Seuss and his colorful characters come to life on stage in this musical for all ages. The Cat in the Hat takes us through the story of Horton the Elephant and his quest to prove that Whos really do exist. The story: A young boy, JoJo, discovers a red-and-white-striped hat. The Cat in the Hat suddenly appears and brings along with him Horton the Elephant, Gertrude McFuzz, the Whos, Mayzie La Bird and Sour Kangaroo. Horton hears a cry for help. He follows the sound to a tiny speck of dust floating through the air and realizes that there are people living on it. They are so small they can't be seen – the tiny people of Whoville. Horton places them safely onto a soft clover. Sour Kangaroo thinks Horton is crazy for talking to a speck of dust. As Horton is left alone with his clover, the Cat thrusts Jojo into the story. Horton discovers much more about the Whos and their tiny town of Whoville while Jojo's imagination gets the better of him. Horton and Jojo hear each other and become friends when they realize their imaginations are so much alike. Gertrude writes love songs about Horton. She believes Horton doesn't notice her because of her small tail. Mayzie appears with her Bird Girls and offers Gertrude advice which leads her to Doctor Dake and his magic pills for “amayzing” feathers. -

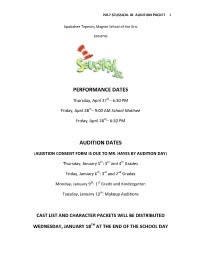

Seussical Jr AUDITION PACKET

2017 SEUSSICAL JR. AUDITION PACKET 1 Apalachee Tapestry Magnet School of the Arts presents PERFORMANCE DATES Thursday, April 27th– 6:30 PM Friday, April 28th– 9:00 AM School Matinee Friday, April 28th– 6:30 PM AUDITION DATES (AUDITION CONSENT FORM IS DUE TO MR. HAYES BY AUDITION DAY) Thursday, January 5th: 5th and 4th Grades Friday, January 6th: 3rd and 2nd Grades Monday, January 9th: 1st Grade and Kindergarten Tuesday, January 10th: Makeup Auditions CAST LIST AND CHARACTER PACKETS WILL BE DISTRIBUTED WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 18TH AT THE END OF THE SCHOOL DAY 2017 SEUSSICAL JR. AUDITION PACKET 2 INTRODUCTION Your son or daughter is interested in participating in this year’s musical, “Seussical Jr,” on April 27th and 28th, 2017 at Apalachee Tapestry Magnet School of the Arts. This show provides a great opportunity for all interested students to work together, regardless of experience or grade level! It also is a big undertaking, and we need to know that the students who choose to participate will be able to commit to the time and attention required. Please read through this packet and do not hesitate to contact Mr. Hayes ([email protected]) if you have any questions. AUDITION REQUIREMENTS ü Choose one character from the audition packet and memorize that character’s monologue and song. Song clips can be found on Mr. Hayes’ website under “Important Documents.” ü Read through and complete the attached Audition Consent form. THIS MUST BE RETURNED BY THE CHILD’S AUDITION DAY. ü Parents must attend the MANDATORY Parent Meeting: JANUARY 23RD 6:30 PM. -

Fhnews Oct20

Forest Hill News October 2020 Forest Hill News—Page 1 THEODOR GEISEL The young man, Theodor Geisel, was already a successful illustrator and cartoonist in New York, but he wanted to be an author. So, Theodor wrote a book which he enthusiastically submitted to a publisher. It was rejected. And that rejection was followed by another, and another, and another. There were twenty-seven in all. No one likes to be rejected. Theodor lost his enthusiasm. Walking along Madison Avenue with the unwanted manuscript under his arm, it was Theodor’s intention to burn it as soon as he returned to his apartment. Whether it was providential or serendipitous doesn’t matter, but it mattered a lot that on his walk home Theodor happened to run into Mike McClintock, an old friend from student years at Dartmouth College. The friends chatted, but before going their separate ways Geisel’s friend inquired what was in that big bundle tucked under his arm. After pouring out his sad story of serial rejections, the friend announced that he had recently been hired as the Children’s Book Editor for Vanguard Press, and he was on his way to his office for his first day on the job, and if Geisel wanted to accompany him he would be quite willing to look at the oft rejected manuscript. The novitiate editor recognized the manuscript as something quite different for a children’s book, almost “off the wall,” but he liked what he saw, both in the text and the wild illustrations. The book, And to Think What I Saw on Mulberry Street, first published in 1937, was an immediate best seller. -

1 Works Cited Primary Sources Army Photo. Dr. Seuss' Army Career

1 Works Cited Primary Sources Army photo. Dr. Seuss' Army Career. US Dept of Defense, www.defense.gov/Explore/Features/story/Article/1769871/dr-seuss-army-career/. Accessed 2 Feb. 2021. This is a photo of Theodor Geisel when he was an Army Major. While in the army, Giesel was in command of the 1st Motion Picture Unit . It will be used in our project as a visual on our website along with quotes about his time in the Army during WWII. Barajas, Joshua. "8 Things You Didn't Know about Dr. Seuss." PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 22 July 2015, www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/8-things-didnt-know-dr-seuss. This photograph is a cartoon from the Jack O Lantern when Geisel wrote for them, showing the prolific nature and more adult humor he once had when writing and creating for others. Bryson, John. "Children's Book Author/Illustrator Theodor Seuss Geisel Posing with..." Getty Images, 1959, www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/childrens-book-author-illustrator-theodor-seuss -geisel-news-photo/50478492?adppopup=true. Photograph taken of Seuss with 3D models of his characters, most likely for an article or cover of literature. Taken by John Bryson. Cahill, Elizabeth N., et al. Seuss in Springfield, www.seussinspringfield.org/. Photographs of Seuss at an early age, will be used in the Bio page to show the continuity of his German heritage. 2 Don't let them carve THOSE faces on our mountains, December 12, 1941, Dr. Seuss Political Cartoons. Special Collection & Archives, UC San Diego Library Cartoons that display his early characters and how they showed his ideas against Germany and anti-semitism Dr. -

Extensive Biography

Dr. Seuss Biography SAPER GALLERIES and Custom Framing 433 Albert Avenue East Lansing, Michigan 48823 517/351-0815 Décor Magazine’s selection as number one gallery for 2007 [email protected] www.sapergalleries.com Official Dr. Seuss Biography “The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go.” –from I Can Read With My Eyes Shut! I. Early Years A. Childhood B. Dartmouth C. Oxford II. Early Career A. Judge , Standard Oil/Advertising B. World War II C. Publishing III. Personal life and interests A. Art B. Helen Palmer Geisel C. Various friends D. The Tower/writing habits E. Issues/opinions/inspirations IV. Later years A. Audrey Geisel B. Honors/tributes C. Other media V. Legacy A. Translations, languages B. Posthumous works/tribute works C. New media forms, Seuss Enterprises 1 Dr. Seuss Biography From the Official Dr. Seuss Biography I. Early Years A. Childhood Yes, there really was a Dr. Seuss. He was not an official doctor, but his prescription for fun has delighted readers for more than 60 years. Theodor Seuss Geisel (“Ted”) was born on March 2, 1904, in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father, Theodor Robert, and grandfather were brewmasters and enjoyed great financial success for many years. Coupling the continual threats of Prohibition and World War I, the German-immigrant Geisels were targets for many slurs, particularly with regard to their heritage and livelihoods. In response, they were active participants in the pro-America campaign of World War I. Thus, Ted and his sister Marnie overcame such ridicule and became popular teenagers involved in many different activities. -

Dr. Seuss Biography (1280L)

Santa Ana High School Article of the Week #12 Dr. Seuss Biography (1280L) Instructions: READ and ANNOTATE using CLOSE reading strategies. Step 1: Skim the article using these symbols as you read: (+) agree, (-) disagree, (*) important, (!) surprising, (?) wondering Step 2: Number the paragraphs. Read the article carefully and make notes in the margin. Notes should include: o Comments that show that you understand the article. (A summary or statement of the main idea of important sections may serve this purpose.) o Questions you have that show what you are wondering about as you read. o Notes that differentiate between fact and opinion. o Observations about how the writer’s strategies (organization, word choice, perspective, support) and choices affect the article. Step 3: A reread noting anything you may have missed during the first read. Student ____________________________Class Period__________________ Notes on my thoughts, Dr. Seuss Biography reactions and questions as I Synopsis read: Theodor Seuss Geisel was born on March 2, 1904, in Springfield, Massachusetts. He published his first children's book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, under the name of Dr. Seuss in 1937. Next, came a string of best sellers, including The Cat in the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham. His rhymes and characters are beloved by generations. Early Life Theodor Seuss Geisel was born on March 2, 1904, in Springfield, Massachusetts to Theodor Robert Geisel, a successful brew master, and Henrietta Seuss Geisel. At age 18, Geisel left home to attend Dartmouth College, where he became the editor in chief of its humor magazine, Jack-O-Lantern. -

Big Green Book of Beginner Books Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BIG GREEN BOOK OF BEGINNER BOOKS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dr. Seuss | 256 pages | 11 Aug 2009 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375858079 | English | New York, United States Big Green Book of Beginner Books PDF Book This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. Seuss' How the Grinch Stole Christmas! By default, I give the books four-stars because they're good at what they're intended to do, which is to keep the attention of children and introduce them to literature. It's Not Easy Being a Bunny. Essentially people buy strangers books! Ten Apples Up On Top! I'm loving this book right now! There are no discussion topics on this book yet. Education: B. Report incorrect product information. Mercer Mayer. We try our best to present to you the best books out there. Barry Wittenstein. Martin Luther King, Jr. More filters. Pickup not available. Paws and Claws. Seuss: How the Grinch Stole Christmas! I can also add some of the money from the sale of these to this pot. We're committed to providing low prices every day, on everything. It came right on time, actually a day earlier than when it was due. Seuss himself, Beginner Books are fun, funny, and easy to read. The greatest book ever published. Ask a question Ask a question If you would like to share feedback with us about pricing, delivery or other customer service issues, please contact customer service directly. Thank you for signing up! Thank you. Patricia Polacco. Related Articles. This website does not list what books I have, or what books I can get. -

Dr. Seuss Goes to War: the World War II Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisel by Richard H

Dr.. Seuss Goes to War A little known fact about the World War II-era is that series of political cartoons by the famed children's author Dr. Seuss impacted the American isolationist mind set. More than 200 of the cartoons were assembled for the first time in the book Dr. Seuss Goes to War: The World War II Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisel by Richard H. Minear. Minear is a professor of history at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and one of the country's leading historians of Japan during World War II. This exhibit, guest-curated by Minear, is based in part on his book and is the first exhibit to examine the political side of Dr. Seuss. Minear said that there is "a disconnect between what we usually think of as Dr. Seuss and the content of the cartoons." However, many Dr. Seuss's whimsical children's books also contain serious themes. Yertle the Turtle, for example, is a cautionary tale against dictators. The Lorax contains a strong environmental message. The Sneetches is a plea for racial tolerance. Horton Hears a Who is a parable about the American Occupation of Japan. And The Butter Battle Book pillories the Cold War and nuclear deterrence. Even the Cat in the Hat's famous red-and-white-striped hat has a political predecessor in the top hat Uncle Sam wears in Dr. Seuss's wartime cartoons. Some of these characters, such as a Sneetch-type creature and a prototype of Yertle the Turtle, made their first appearance not in Dr. -

Open Doctor on the Warpath.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH DOCTOR ON THE WARPATH: HOW THE SECOND WORLD WAR MADE THEODOR SEUSS GEISEL BRANDON ELLIOTT GATTO Spring 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Sanford Schwartz Associate Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Janet Lyon Associate Professor of English, Women’s Studies, and Science, Technology, and Society Honors Adviser Daniel Hade Associate Professor of Language and Literacy Second Reader * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i Abstract The stories of Dr. Seuss, one of the most popular and best-selling children’s authors of all time, are often associated with fantastic characters, whimsical settings, and witty rhymes. While such facets are commonplace in the world of children’s literature, the ability of Theodor Seuss Geisel to transform reality into a nonsense arena of eloquence and simplicity is perhaps what made him a symbol of American culture. Despite his popularity, however, the historical context and primary influences of the author’s memorable lessons are not critically evaluated as much as those of other genre personalities. Many of his children’s books have clear, underlying messages regarding societal affairs and humanity, but deeper connections have yet to be established between Geisel’s pedagogical themes and personal agenda. Accordingly, this thesis strives to prove that the most inherent and significant influences of Dr. Seuss derive from his experiences as a political cartoonist during the Second World War era. Having garnered little recognition before World War II, Geisel’s satirical political illustrations and subsequent war-based work helped shape him into the rousing, unparalleled children’s author that generations have come to read and remember. -

Dr. Seuss Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1000043t Online items available Dr. Seuss Collection Special Collections & Archives Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2005 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Dr. Seuss Collection MSS 0230 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Dr. Seuss Collection Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0230 Physical Description: 197.7 Linear feet (25 archives boxes, 7 records cartons, 4 card file boxes, 2 phonograph disc boxes, 559 mapcase folders, 75 flat box folders and 35 art bin items) Date (inclusive): 1919 - 2003 Abstract: Manuscripts and drawings of Theodor S. Geisel, author and illustrator known internationally as Dr. Seuss. The collection (1919-1992) includes early drawings, manuscripts and drawings for the majority of his children's books, scripts and storyboards for Dr. Seuss films, television specials and theatre productions, advertising artwork, magazine stories, speeches, awards, memorabilia, fan mail, Dr. Seuss products and photographs. Also included are videorecordings and cassette audiorecordings of UCSD events held to commemorate Geisel's life and work. The collection is arranged in twelve series: 1) BIOGRAPHICAL MATERIAL, 2) BOOKS, 3) SCRIPTS, SCREENPLAYS AND ADAPTATIONS, 4) ADVERTISING ARTWORK, 5) MAGAZINE STORIES AND CARTOONS, 6) WRITINGS, SPEECHES AND TEACHING PROGRAMS, 7) AWARDS AND MEMORABILIA, 8) FAN MAIL, 9) SEUSS PRODUCTS, 10) BOOK PROMOTION MATERIALS, 11) PHOTOGRAPHS, and 12) UCSD EVENTS. Scope and Content of Collection The Dr. Seuss Collection documents the artistic and literary career of Theodor Seuss Geisel, popularly know as Dr. -

Dr. Seuss: the Man, the War, and the Work

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 4-2000 Dr. Seuss: The Man, the War, and the Work Katy Anne Rice University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Rice, Katy Anne, "Dr. Seuss: The Man, the War, and the Work" (2000). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/426 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. --~~------------------------------------------------------------ Appendix D - UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL Name: __ ~~~---~i~~------------------------------------- ColI e g e: __.4.r:.b_.d_S.f.J~~f.:!-...s....__ Oep a r tm en t: _L~:s~ ____________ _ Fa cuI ty Men to r: --..e~c.::k-A--K~LL1--------------------------- PROJECT TITLE: ----Df---.s.<.J.t~~-:.--~-~_t--~----- ______ U1~~-~---~--klOJ-~---------------------------- I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors level undergraduate research in this field. Signed: __-d~ .... -L.Lf:~ _____________________ , Fa cui tv :VIe n to r Date: --.tb-7A~_________ _ Comments (Optional): /7; CdVvItuUt/J ~ ~ 7-/c. ~ 4//~.d /~J~) /h~~ 1Af /1Ct!~ ~ ./1e#4~ ;/h&~. 27 DR. !IU!!: TIll MAN, TIll WA., AND TIll WO.1f By: Katy Rice Advisor: Dr.