Dr. Seuss: the Man, the War, and the Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Thing One!] Oh the Places He Went! Yes, There Really Was a Dr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3069/thing-one-oh-the-places-he-went-yes-there-really-was-a-dr-3069.webp)

[Thing One!] Oh the Places He Went! Yes, There Really Was a Dr

There’s Fun to Be Done! [Thing One!] Oh The Places He Went! Yes, there really was a Dr. Seuss. He was not an official doctor, but his Did You Know? prescription for fun has delighted readers for more than 60 years. The proper pronunciation of “Seuss” is Theodor Seuss Geisel (“Ted”) was actually “Zoice” (rhymes with “voice”), being born on March 2, 1904, in a Bavarian name. However, due to the fact Springfield, Massachusetts. His that most Americans pronounced it father, Theodor Robert, and incorrectly as “Soose”, Geisel later gave in grandfather were brewmasters and stopped correcting people, even quipping (joking) the mispronunciation was a (made beer) and enjoyed great financial success for many good thing because it is “advantageous for years. Coupling the continual threats of Prohibition an author of children’s books to be (making and drinking alcohol became illegal) and World associated with—Mother Goose.” War I (where the US and other nations went to war with Germany and other nations), the German-immigrant The character of the Cat in “Cat in the Hat” Geisels were targets for many slurs, particularly with and the Grinch in “How the Grinch Stole regard to their heritage and livelihoods. In response, they Christmas” were inspired by himself. For instance, with the Grinch: “I was brushing my were active participants in the pro-America campaign of teeth on the morning of the 26th of last World War I. Thus, Ted and his sister Marnie overcame December when I noted a very Grinch-ish such ridicule and became popular teenagers involved in countenance in the mirror. -

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Download the Dr. Seuss Worksheet: Egg to Go

Watch an egg? What a job! What a hard thing to do! They can crack! They can smash! It all comes down to you And how careful you are and how warm it will be Underneath you, up high in a very high tree! When Horton the Elephant hatches the egg Egg He sits in the rain and the snow, ’til I’d beg For a rest! We can help! Make a carrying case activity 3 activity So Horton can egg-sit in some warmer place! to Go! So join us today–help an egg take a trip, By making a case that’s both sturdy and hip! Exhibition developed by Exhibition sponsored by “The elephant laughed. ‘Why, of all silly things! Try I haven’t feathers and I haven’t wings. ME on your egg? Why, that doesn’t make sense... Did you know? Your egg is so small, ma’am, and I’m so immense!’” It! —Dr. Seuss The idea for Horton Hatches the Egg came to Dr. Seuss one In Dr. Seuss’s book, Horton Hatches the Egg, a very generous elephant agrees to sit day when he happened to hold on a bird’s egg until it hatches, while the bird goes off on vacation. Horton endures a drawing of an elephant up to many challenges when some people move his tree (with him and the nest still in it) the window. As the light shone and cart it off to the circus. But, in the end, the elephant is rewarded for his patience through the tracing paper, the because the bird that comes out of the egg looks like a small elephant with wings. -

Fun Facts About Dr. Seuss • Dr Seuss’S Real Name Was Theodor Seuss Geisel but His Friends and Family Called Him ‘Ted’

Fun Facts about Dr. Seuss • Dr Seuss’s real name was Theodor Seuss Geisel but his friends and family called him ‘Ted’. • Theodor Seuss Geisel was born on 2 March 1904 in Springfield, Massachusetts. • Ted worked as a cartoonist and then in advertising in the 1930s and 1940s but started contributing weekly political cartoons to a magazine called PM as the war approached. • The first book that was both written and illustrated by Theodor Seuss Geisel was And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. The book was rejected 27 times before being published in 1937. • The Cat in the Hat was written as a result of a 1954 report published in Life magazine about illiteracy among school children. A text-book editor at a publishing company was concerned about the report and commissioned Ted to write a book which would appeal to children learning to read, using only 250 words given to him by the editor. • Ted was fascinated by research into how babies develop in the womb and whether they can hear and respond to the voices of their parents. He was delighted to find that The Cat in the Hat had been chosen by researchers to be read by parents to their babies while the babies were still in utero . • Writing as Dr Seuss, Theodor Seuss Geisel wrote and illustrated 44 children's books. and These books have been translated into more than 15 languages and have sold over 200 million copies around the world. Complete List of Dr Seuss Books And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street (1937) The 500 Hats Of Bartholomew Cubbins (1938) The King's Stilts (1939) -

Filosofická Fakulta Masarykovy Univerzity

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Magisterská diplomová práce Erika F eldová 2020 Erika Feldová 20 20 Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies North American Culture Studies Erika Feldová From the War Propagandist to the Children’s Book Author: The Many Faces of Dr. Seuss Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A, Ph. D. 2020 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature Acknowledgement I would like to thank my family and friends for supporting me throughout my studies. I could never be able to do this without you all. I would also like to thank Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A, Ph. D. for all of his help and feedback. Erika Feldová 1 Contents From The War Propagandist to the Children’s Book Author: the Many Faces of Dr. Seuss............................................................................................................................. 0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 5 Geisel and Dr. Seuss ..................................................................................................... 7 Early years .................................................................................................................. -

Grappling with Seuss by Rev. Michelle Collins, Delivered March 2, 2014 (Dr

Grappling with Seuss by Rev. Michelle Collins, delivered March 2, 2014 (Dr. Seuss’s 110th birthday) When How the Grinch Stole Christmas was published, it only had two colors, red and green. Art director Cathy Goldsmith was assigned the job of creating a four-color version of illustrations from the book for a puzzle. This project ended up having an unexpected twist in it. When she first sent Geisel her sketch, he called her right back with a problem. “You know what’s wrong? You need some color in the snow.” “What do you mean? Snow is white!” “No,” he says. “Look here, it’s too white. You need a little color so it doesn’t blind you.” He grabbed his color chart and gave her a number for pale mint green for her snow. Green snow! What was he thinking?!? But she went with it, and put green snow into the puzzle picture. And the crazy thing is, it worked. The other colors in the picture dominated and the pale green snow was a soft snow-white.1 Only Dr. Seuss could make green snow that works as snow! Today our celebration of Dr. Seuss in our service is in honor of today’s being his 110th birthday. Theodor Geisel went by the pen name Dr. Seuss for most of his children’s books, and occasionally Theo LeSieg for books that he wrote but others illustrated. He wrote 46 books as Dr. Seuss over the course of his life. Now while we love to “claim” people as UU’s, Dr. -

Dr. Seuss's Horse Museum Lesson Plans

What’s it all about? A visit to an art museum entirely dedicated to horses invites readers to think about how artists share their ideas with us, and how the art they make is shaped by their experiences. While focused on visual art, Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum offers a perfect springboard to explore language arts and history at the same time. An energetic and knowledgeable horse tour guide (yes, a horse!) shepherds young visitors through a museum featuring reproductions of real paintings, sculptures, and textiles. Our equine guide asks the kids to not just look at the art, but also to think about the artist and what they thought, felt, and wanted to tell us when creating their piece. He invites the museum visitors and readers to Look, Think, and Talk. Explore point of view, meaning, artistic expression, and interpretation with Dr. Seuss’s Horse Museum. Note to teachers: Most of the ideas here are adaptable to different age groups, so read through the activities for all ages. You can adapt activities based on your needs or interests. You’ll find lots of interesting ideas. Text TM & copyright © by Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. 2019. Illustrations copyright © 2019 by Andrew Joyner Seuss Enterprises, L.P. TM & copyright © by Dr. Text A never-before- published book about creating and looking at art! Based on a manuscript and sketches discovered in 2013, this book is like a visit to a museum—with a horse as your guide! Explore how different artists have seen horses, and maybe even find a new way of looking at them yourself. -

Beloved Holiday Movie: How the Grinch Stole Christmas! 12/9

RIVERCREST PREPARATORY ONLINE SCHOOL S P E C I A L I T E M S O F The River Current INTEREST VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3 DECEMBER 16, 2014 We had our picture day on Beloved Holiday Movie: How the Grinch Stole Christmas! 12/9. If you missed it, there will be another opportunity in the spring. Boris Karloff, the voice of the narrator and the Grinch in the Reserve your cartoon, was a famous actor yearbook. known for his roles in horror films. In fact, the image most of us hold in our minds of Franken- stein’s monster is actually Boris Karloff in full make up. Boris Karloff Jan. 12th – Who doesn’t love the Grinch Winter Break is Is the reason the Grinch is so despite his grinchy ways? The Dec. 19th popular because the characters animated classic, first shown in are lovable? We can’t help but 1966, has remained popular with All class work must adore Max, the unwilling helper of children and adults. be completed by the Grinch. Little Cindy Lou Who The story, written by Dr. Seuss, the 18th! is so sweet when she questions was published in 1957. At that the Grinch’s actions. But when the I N S I D E time, it was also published in Grinch’s heart grows three sizes, THIS ISSUE: Redbook magazine. It proved so Each shoe weighed 11 pounds we cheer in our own hearts and popular that a famous producer, and the make up took hours to sing right along with the Whos Sports 2 Chuck Jones, decided to make get just right. -

Seussical Study Guide Oct 27.Indd

Lorraine Kimsa Theatre for Young People EDUCATION PARTNERS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Allen MacInnis MANAGING DIRECTOR Nancy J. Webster NOV. 12 to DEC. 31, 2006 MUSIC BY STEPHEN FLAHERTY, LYRICS BY LYNN AHRENS BOOK BY LYNN AHRENS AND STEPHEN FLAHERTY CO-CONCEIVED BY LYNN AHRENS, STEPHEN FLAHERTY AND ERIC IDLE BASED ON THE WORKS OF DR. S EUSS AC DIRECTED BY ALLEN M INNIS Study Guide by Aida Jordão and Stephen Colella Design and layout by Amy Cheng THE STUDY GUIDE 1 Curriculum Connection: Choreography and Movement 10 Themes Monkey Around Seussical and the Ontario Curriculum Find your Animal Twin THE COMPANY 2 Curriculum Connection: Animals and Habitat 11-12 Cast Find the Habitat Creative Team Living Things and their Habitats THE PLAY 2 Curriculum Connection: Nature and Conservation 13 Synopsis Ways to Protect Threatened Animals Invisible Dangers BACKGROUND INFORMATION 3 About Dr. Seuss Curriculum Connection: Community and Government 14-17 How Seussical came to be Children’s Rights A Citizen’s Duties THE INTERPRETATION 4-7 Responsibility and Accountability A note from the Director A note from the Musical Director Curriculum Connection: Portraiture, Community 18-19 A note from the Costume Designer The Whos in your World A note from the Set and Props Designer Curious Creatures Characters RESOURCES 20 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES Curriculum Connection: Musical Performance 8-9 Sheet music for “Oh, the Thinks you can Think” Lyrics and Arrangement Song Genres LIVE THEATRE IS AN ACTIVE EXPERIENCE GROUND RULES: THEATRE IS A TWO-WAY EXCHANGE: As members of the audience, you play an important part in the Actors are thrilled when the audience is success of a theatrical performance. -

B. Academy Award Dr. Seuss Wo

1. Dr. Seuss is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author. In addition to this, what other award has he won? B. Academy Award Dr. Seuss won two Academy Awards. He won his first Oscar for writing an animated short called “Gerald McBoing-Boing” in 1951. He also won an Academy Award for a documentary called “Design for Death” about Japanese culture. 2. Which of the following Dr. Seuss books was pulled from the shelf? A. “The Butter Battle Book” Published in 1984, “The Butter Battle Book” actually dealt with the nuclear arms race. It was pulled from the shelves after six months because of its underlying references to the Cold War, and the arms race then taking place between Russia and the United States. Interestingly enough, the story was actually made into a short video piece and broadcast in Russia. 3. True or false, though deceased, Dr. Seuss still has new books being published? A. True True. Random House Children’s Books said it will publish Seuss’ manuscript found in 2013 by his widow with illustrations. The book is titled, “What Pet Should I Get” and is set for release on July 28, 2015. Read more. 4. Truffula Trees, Swomee-Swans, and Brown Bar-ba-loots are found in which Seuss tale? E. “The Lorax” A fairly grim tale compared to “Green Eggs and Ham” or “The Cat in the Hat,” “The Lorax” reflects the era in which it was written. In 1971, when the book was released, the U.S. was embroiled in environmental issues left over from the 1960s. -

SEUSSICAL This December, W.F. West Theatre Continues Its Tradition

SEUSSICAL This December, W.F. West Theatre continues its tradition of bringing children’s theatre to our community when we present: Seussical. The amazing world of Dr. Seuss and his colorful characters come to life on stage in this musical for all ages. The Cat in the Hat takes us through the story of Horton the Elephant and his quest to prove that Whos really do exist. The story: A young boy, JoJo, discovers a red-and-white-striped hat. The Cat in the Hat suddenly appears and brings along with him Horton the Elephant, Gertrude McFuzz, the Whos, Mayzie La Bird and Sour Kangaroo. Horton hears a cry for help. He follows the sound to a tiny speck of dust floating through the air and realizes that there are people living on it. They are so small they can't be seen – the tiny people of Whoville. Horton places them safely onto a soft clover. Sour Kangaroo thinks Horton is crazy for talking to a speck of dust. As Horton is left alone with his clover, the Cat thrusts Jojo into the story. Horton discovers much more about the Whos and their tiny town of Whoville while Jojo's imagination gets the better of him. Horton and Jojo hear each other and become friends when they realize their imaginations are so much alike. Gertrude writes love songs about Horton. She believes Horton doesn't notice her because of her small tail. Mayzie appears with her Bird Girls and offers Gertrude advice which leads her to Doctor Dake and his magic pills for “amayzing” feathers. -

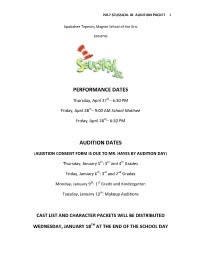

Seussical Jr AUDITION PACKET

2017 SEUSSICAL JR. AUDITION PACKET 1 Apalachee Tapestry Magnet School of the Arts presents PERFORMANCE DATES Thursday, April 27th– 6:30 PM Friday, April 28th– 9:00 AM School Matinee Friday, April 28th– 6:30 PM AUDITION DATES (AUDITION CONSENT FORM IS DUE TO MR. HAYES BY AUDITION DAY) Thursday, January 5th: 5th and 4th Grades Friday, January 6th: 3rd and 2nd Grades Monday, January 9th: 1st Grade and Kindergarten Tuesday, January 10th: Makeup Auditions CAST LIST AND CHARACTER PACKETS WILL BE DISTRIBUTED WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 18TH AT THE END OF THE SCHOOL DAY 2017 SEUSSICAL JR. AUDITION PACKET 2 INTRODUCTION Your son or daughter is interested in participating in this year’s musical, “Seussical Jr,” on April 27th and 28th, 2017 at Apalachee Tapestry Magnet School of the Arts. This show provides a great opportunity for all interested students to work together, regardless of experience or grade level! It also is a big undertaking, and we need to know that the students who choose to participate will be able to commit to the time and attention required. Please read through this packet and do not hesitate to contact Mr. Hayes ([email protected]) if you have any questions. AUDITION REQUIREMENTS ü Choose one character from the audition packet and memorize that character’s monologue and song. Song clips can be found on Mr. Hayes’ website under “Important Documents.” ü Read through and complete the attached Audition Consent form. THIS MUST BE RETURNED BY THE CHILD’S AUDITION DAY. ü Parents must attend the MANDATORY Parent Meeting: JANUARY 23RD 6:30 PM.