Instructional Design Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universal Instructional Design Implementation Guide Credits

The Universal Instructional Design Implementation Guide Credits Written by: Jaellayna Palmer Project Manager and Instructional Designer Universal Instructional Design Project Teaching Support Services University of Guelph Aldo Caputo Manager Learning Technology & Courseware innovation Teaching Support Services University of Guelph Designed by: Doug Schaefer Graphic Designer Teaching Support Services University of Guelph Funded by: The Learning Opportunities Task Force Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities, Government of Ontario 2002-03 Acknowledgements Teaching Support Services would like to acknowledge and offer thanks to the following contributors to this project: • The Learning Opportunities Task Force, Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities, Government of Ontario, which provided funding during 2002-03. • Linda Yuval, Research Assistant for the UID project, and her advisor, Professor Karen Korabik, Department of Psychology, University of Guelph. • Personnel within the Centre for Students with Disabilities, and the Learning Commons, University of Guelph. • Professors and TAs who participated in our course projects. • Students who volunteered to participate in the UID project and who provided their feedback. Universal Instructional Design Implementation Guide ii Table of Contents Universal Instructional Design ......................................................................................................................1 Universal Instructional Design Principles (Poster) ........................................................................................4 -

Designing for Online Interaction: Scaffolded and Collaborative Interventions in a Graduate-Level Blended Course

The Call Triangle: student, teacher and institution Designing for online interaction: Scaffolded and collaborative interventions in a graduate-level blended course Claudia Álvarez and Liliana Cuesta * Universidad de La Sabana,Campus Universitario Puente del Común,Chía,Colombia Abstract This article examines types of interaction from the perspective of intervening agents and interaction outcomes. We argue that the strategic combination of these types of interaction with certain core features (such as dosified input, attainable goal-setting, personalization and collaboration) contribute to creating a more effective relationship between instructional design, use and the interactional purposes of learning activities. The paper also offers instructors and course designers various considerations regarding the pedagogical nature of learning activities and the actions that both learners and instructors can carry out to optimize the online educational experience. Consideration for emergent trends in research on related areas are also presented. Keywords : online interaction; instructional design; course design; e-learning; scaffolding 1. Introduction In the context of online education, constructs such as instructional design, implementation of learning activities, scaffolding, assessment, resource selection and interaction among agents are seen as essential attributes of online courses and/or modules (Cuesta, 2010a). In educational scenarios, the interrelation of all these components has a direct impact on the learning performance of the students -

Project Management in Instructional Design

PROJECT MANAGEMENT IN INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN by Shamon A. Allen A dissertation presented to the faculty of The International Institute for Innovative Instruction In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PROFESSIONAL STUDIES in Instructional Design Leadership FRANKLIN UNIVERSTIY Columbus, Ohio December 2020 Joel Gardner, Ph.D., Faculty Mentor and Chair Lewis Chongwony, Ph.D., Committee Member Niccole Hyatt, Ph.D., Committee Member Franklin University This is to certify that the dissertation prepared by Shamon Allen “Project Management in Instructional Design” Has been approved by his committee as satisfactory completion of the dissertation requirements for the degree of Doctor of Professional Studies in Instructional Design Leadership 12/16/2020 Joel Gardner, Ph.D., Committee Chair Niccole Hyatt Niccole Hyatt (Dec 16, 2020 08:25 EST) 12/16/2020 Niccole Hyatt, Ph.D., Committee Member 12/16/2020 Lewis Chongwony, Ph.D., Committee Member Yi Yang Yi Yang (Dec 16, 2020 21:36 EST) 12/16/2020 Yi Yang, Ph.D., Program Chair, DPS 12/17/2020 Wendell Seaborne, Ph.D., Dean, Doctoral Studies ii Copyright Shamon A. Allen 2020 iii ABSTRACT Project Management in Instructional Design by Shamon A. Allen, Doctor of Professional Studies Franklin University, 2020 Major Professor: Dr. Joel L. Gardner Department: International Institute for Innovative Instruction This study surveyed 86 instructional design professionals based on a two-part approach to identify and validate the most critical instructional design project management competencies. First, a systematic review of instructional design project management literature was conducted to identify key project management competencies. Next, a survey instrument was created based on common themes identified during the systematic analysis of qualitative study results on instructional design project management competencies. -

WHAT IS LEARNING EXPERIENCE DESIGN? & Why It Matters PRESENTERS

WHAT IS LEARNING EXPERIENCE DESIGN? & why it matters PRESENTERS Kristen Hernandez Lydia Treadwell Learning Experience Designer Learning Experience Designer LSU Digital & Continuing Education LSU Digital & Continuing Education [email protected] [email protected] OVERVIEW • What is Learning Experience Design (LXD)? • LXD Development Tools • Empathy mapping • “Pillars” of LXD • LXD Matrix • Application activity LXD=ID+UX Learning Experience Design (LXD) is interdisciplinary approach to developing well-designed learning environments that employ both sound Instructional Design (ID) and User Experience Design (UXD) techniques. LXD=ID+UX1 learning theories alignment maps design models storyboards instructional analysis item analysis Instructional Design LXD=ID+UX2 empathy-mapping prototyping personas iterative design scenarios user testing Learner-Centered Design Empathy map The Four Pillars of Learning Experience INSTRUCTION • approach to the method of instruction, tailored for the context, content, and learner. • creating a meaningful learning experience • address the gaps that exist between the learner and the desired outcome • practice and apply new skills in real-world or authentic contexts CONTENT • appropriate selection of content that supports acquisition of outcomes • outline the necessary knowledge, skills, and resources needed for learners to fulfill those outcomes. • effective arrangement of instructional material including the content flow, chunking, and organization • content structured in a way that makes the most logical and relevant -

Pleksiglass Som Lokke Mat Og Mulighet Plexiglas As a Lure And

Pleksiglass som lokke mat og mulighet Pleksiglass som lokke mat og mulighet Plexiglas as a lure and Plexiglas potential By Liam Gillick Den britiske kunstneren Liam Gillick har gjerne The British artist Liam Gillick is often associated as a lure and blitt forbundet med den relasjonelle estetikken, with relational aesthetics, which emphasises the som la vekt på betrakteren som medskaper av ver- contribution of the viewer to an artwork and tends ket, og som ofte handlet om å tilrettelegge steder to focus on defining places and situations for social og situasjoner for sosial interaksjon. Men i mot- interaction. But in contrast to artists like Rirkrit setning til kunstnere som Rirkrit Tiravanija, som Tiravanija, who encourages audience-participation inviterte publikum til å samtale over et måltid, in a meal or a conversation, Gillick’s scenarios do gir ikke Gillicks scenarier inntrykk av å være laget not seem constructed for human activity. Instead, for menneskelig aktivitet. Installasjonene hans i his installations of Plexiglas and aluminium are potential pleksiglass og aluminium handlere snarere om concerned with the analysis of structures and types å analysere sosiale strukturer og organisasjons- of social organisation, and with the exploration of måter, og undersøke de romlige forutsetningene the spatial conditions for human interaction. Rec- for menneskelig interaksjon. Inspirert av hans ognising Gillick’s carefully considered relationship reflekterte forhold til materialene han jobber to the materials he uses, we invited him to write By med, ba vi ham skrive om sin interesse for pleksi- about his interest in Plexiglas, a material he has glass, et materiale han har arbeidet med i over 30 år. -

Form, Function and Symbolism in Furniture Design, Fictive Eroision and Social Expectations

shutter speed form, function and symbolism in furniture design, fictive eroision and social expectations SHUTTER SPEED Form, function and symbolism in furniture design, fictive erosion and social expectations SHUTTER SPEED Form, function and symbo lism in furniture design, fictive erosion and social expectations Kajsa Melchior MA Spatial Design Diploma project VT 2019 Konstfack Kajsa Melchior MA Spatial Design Diploma project VT 2019 Konstfack The concept of time is central to geological thought. The processes that shape the surface of the earth acts over vast expenses of time - millions, or even billions of years. If we discount, for the moment, catastrophic events such as earthquakes and landslides, the earth's surface seems relatively stable over the timescales we can measure. Historical records do show the slow diversion of a rivers course, and the silting up of estuaries, for example. But usually we would expect images taken a hundred years ago to show a landscape essentially the same as today's. But imagine time speeding up, so that a million years pass in a minute. In this time frame, we would soon lose our concept of 'solid' earth, as we watch the restless surface change out of all recognition. - Earth’s restless surface, Deirdre Janson-Smith, 1996 1 Table of contents 1. PRELUDE 1.1 Aims, intentions and questions 05-06 1.2 Background 07 2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK - REFERENCES 2.1 Philosophy / Étienne Jules Marey 09-10 2.2 Aesthetics / Max Lamb 11-12 2.3 Criticism / Frederick Kiesler 13-14 2.4 Conclusion 15 3. FICTIVE EROSION 3.1 Methodology as tool 16 3.3 Erosion & Casting techniques 16-18 3.4 Method 19-23 4. -

Department of Art & Design

Whitburn Academy Department of Art & Design Art & Design Studies Learners Higher: Art & Design Studies Design Analyse the factors influencing designers and design practice by Booklet Fashion 1.1 Describing how designers use a range of design materials, techniques and technology in their work 1.2 Analysing the impact of the designers’ creative choices in a range of design work 1.3 Analysing the impact of social and cultural influences on selected designers and their design practice. A study of Coco Chanel Day dress, ca. 1924 Gabrielle Theater suit, 1938, Gabrielle Evening dress, ca. 1926–27 "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883–1971) "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883– Attributed to Gabrielle "Coco" Wool 1971) Silk Chanel (French, 1883–1971) Silk, metallic threads, sequins What is Fashion Design? Fashion design is a form of art dedicated to the creation of clothing and other lifestyle accessories. Modern fashion design is divided into two basic categories: haute couture and ready-to-wear. The haute couture collection is dedicated to certain customers and is custom sized to fit these customers exactly. In order to qualify as a haute couture house, a designer has to be part of the Syndical Chamber for Haute Couture and show a new collection twice a year presenting a minimum of 35 different outfits each time. Ready-to-wear collections are standard sized, not custom made, so they are more suitable for large production runs. They are also split into two categories: designer/creator and confection collections. Designer collections have a higher quality and finish as well as an unique design. They often represent a certain philosophy and are created to make a statement rather than for sale. -

Teaching Sustainable Design Using BIM and Project-Based Energy Simulations

Educ. Sci. 2012, 2, 136-149; doi:10.3390/educsci2030136 OPEN ACCESS education sciences ISSN 2227-7102 www.mdpi.com/journal/education Case Report Teaching Sustainable Design Using BIM and Project-Based Energy Simulations Zhigang Shen *, Wayne Jensen, Timothy Wentz and Bruce Fischer The Durham School of Architectural Engineering and Construction, The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 113 NH, Lincoln, NE 68588-0500, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (W.J.) ; [email protected] (T.W.) ; [email protected] (B.F.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-402-472-9470; Fax: +1-402-472-4087. Received: 11 July 2012; in revised form: 4 August 2012/ Accepted: 20 August 2012/ Published: 27 August 2012 Abstract: The cross-disciplinary nature of energy-efficient building design has created many challenges for architecture, engineering and construction instructors. One of the technical challenges in teaching sustainable building design is enabling students to quantitatively understand how different building designs affect a building’s energy performance. Concept based instructional methods fall short in evaluating the impact of different design choices on a buildings’ energy consumption. Building Information Modeling (BIM) with energy performance software provides a feasible tool to evaluate building design parameters. One notable advantage of this tool is its ability to couple 3D visualization of the structure with energy performance analysis without requiring detailed mathematical and thermodynamic calculations. Project-based Learning (PBL) utilizing BIM tools coupled with energy analysis software was incorporated into a senior level undergraduate class. Student perceptions and feedback were analyzed to gauge the effectiveness of these techniques as instructional tools. -

Lighting for the Workplace

Lighting for the Workplace AWB_Workplace_Q_Produktb_UK.qxd 02.05.2005 10:35 Uhr Seite 3 CONTENTS 3 Foreword by Paul Morrell, 4–5 President of the British Council for Offices INTRODUCTION 6–7 The Changing Corporate Perspective 6–7 WORKPLACE LIGHTING – PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE 8–51 Lighting Research versus the Codes 10–11 – The Lessons of Lighting Research 12–15 – Current Guidance and its Limitations 16–23 Key Issues in Workplace Lighting 24–29 Natural Light, Active Light & Balanced Light 30–37 Further Considerations in Workplace Lighting 38–47 Lighting Techniques – Comparing the Options 48–51 WORKPLACE LIGHTING – APPLICATION AREAS 52–97 Open Plan Offices 56–67 Cellular Offices 68–71 Dealer Rooms 72–75 Control Rooms 76–79 Call Centres 80–83 Communication Areas/Meeting Rooms 84–87 Break-Out Zones 88–91 Storage 92–93 Common Parts 94–97 WORKPLACE LIGHTING – LIGHTING DESIGN 98–135 Product Selector 100–133 Advisory Services 134–135 References & Useful Websites 135 IMPRINT Publisher: Zumtobel Staff GmbH, Dornbirn/A Design: Marketing Communication Reprints, even in part, require the permission of the publishers © 2005 Zumtobel Staff GmbH, Dornbirn/A Paul Morrell President of the British Council for Offices (BCO) London aims to continue being Europe’s leading financial centre and will need more, higher quality office space in the future (photo: Piper’s model of the future City of London, shown at MIPIM 2005) FOREWORD 5 The UK office market, in particular in London, is changing, driven by a number of long-term trends in international banking and finance. Informed forecasts, such as the recent Radley Report*, point, firstly, to a shift towards our capital city, at the expense of Paris and Frankfurt, as Europe’s leading financial centre, with a commensurate pressure on office space. -

University of North Carolina at Charlotte

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA University of North Carolina at Charlotte Invitation for Bid # 66-190015RL Miltimore-Wallis Center Roof Replacement Date of Issue: August 16, 2018 Bid Opening Date: Thursday, August 30, 2018 At 2:00 PM ET Direct all inquiries concerning this IFB to: Robert Law Senior Buyer Email: [email protected] STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHARLOTTE Invitation for Bids # 66-190015RL ______________________________________________________ For internal State agency processing, including tabulation of bids in the Interactive Purchasing System (IPS), please provide your company’s Federal Employer Identification Number or alternate identification number (e.g. Social Security Number). Pursuant to G.S. 132-1.10(b) this identification number shall not be released to the public. This page will be removed and shredded, or otherwise kept confidential, before the procurement file is made available for public inspection. This page is to be filled out and returned with your bid. Failure to do so may subject your bid to rejection. ID Number: ______________________________________________________ Federal ID Number or Social Security Number ______________________________________________________ Vendor Name STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA University of North Carolina at Charlotte Refer ALL Inquiries regarding this IFB to: Invitation for Bids # 66-190015RL Robert Law Bids will be publicly opened: Senior Buyer Thursday, August 30, 2018 @ 2:00 PM ET [email protected] Contract Type: Open Market Using Department: Facilities Management, Design Services EXECUTION In compliance with this Invitation for Bids, and subject to all the conditions herein, the undersigned Vendor offers and agrees to furnish and deliver any or all items upon which prices are bid, at the prices set opposite each item within the time specified herein. -

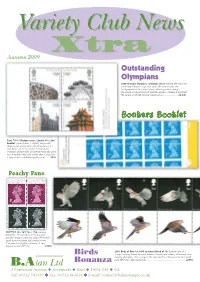

VCN Autumn 2009.Pmd

VarietyVariety ClubClub NewsNews XtraXtra Autumn 2009 Outstanding Olympians 2008 Olympic Handover miniature sheet missing the shiny uv varnished Olympic rings that normally stretch over the background of the entire sheet, affecting every stamp. Previously unrecorded and possibly unique, making it amongst the rarest of all GB missing colour errors ..................... £6,500 Bonkers Booklet Type 7(10) Olympic cover, Questa 10 x 2nd booklet, pane shows a slightly diagonally downwards perforation shift of between 6.5 and 8mm on every stamp. A few minor wrinkles, presumably occurring when the pane was misperforated, but barely detracting from a spectacular exhibition quality item ...... £950 Peachy Pane OCP/PVA 1p +1p/1½p + 1½p, missing phosphor. Previously unrecorded and possibly unique, perfs are good all around apart from the lower-left corner of one 1½p which is slightly trimmed. A very important find [DP2/N] ..................... £2950 2003 Birds of Prey 1st AOP se-tenant block of 10, bottom row of 5 Birds stamps missing brownish grey Queen’s heads and values, all stamps also missing phosphor. One stamp in the top row has a bonus error of a small B.Alan Ltd Bonanza oval litho flaw! Rare [2327ab] ............................................................ £1750 2 Pinewood Avenue ◆ Sevenoaks ◆ Kent ◆ TN14 5AF ◆ UK Tel: 01732 743387 ◆◆◆ Fax: 01732 465651 ◆◆◆ E-mail: [email protected] WELCOME Welcome to Variety Club News Xtra. The list is split into two main parts, the latest issues as supplied on our recent S distribution new issue sendings towards the back and nearer the front a selection of items chosen from stock including interesting and better items, most of which are more elusive, and some of which are one off pieces that do not fall within the scope of standard catalogues, making them highly desirable and extremely unlikely to be offered again. -

Radar Angle of Arrival System Design Optimization Using a Genetic Algorithm

Article Radar Angle of Arrival System Design Optimization Using a Genetic Algorithm Neilson Egger *,†, John E. Ball † and John Rogers † Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 406 Hardy Rd., Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA; [email protected] (J.E.B.); [email protected] (J.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-662-574-0196 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Academic Editor: Mostafa Bassiouni Received: 31 December 2016; Accepted: 20 March 2017; Published: 22 March 2017 Abstract: An approach for using a Genetic Algorithm (GA) to select radar design parameters related to beamforming and angle of arrival estimation is presented in this article. This was accomplished by first developing a simulator that could evaluate the localization performance with a given set of design parameters. The simulator output was utilized as part of the GA objective function that searched the solution space for an optimal set of design parameters. Using this approach, the authors were able to more than halve the mean squared error in degrees of the localization algorithm versus a radar design using human-selected design parameters. The results of this study indicate that this kind of approach can be used to aid in the development of an actual radar design. Keywords: angle of arrival estimation; beamforming; genetic algorithm; radar; optimization 1. Introduction Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are biologically-inspired solutions used for problems where the proposed solutions can be encoded in a population. The GA uses a genetics-based approach to examine the solution space. Herein, a GA is utilized to search over the combination of the number of receive elements in an array, element locations (and therefore, element spacings) and element weightings to minimize the Angle Of Arrival (AOA) error over the receive field of view.