M a X Pla Nck Institute Fo R the S Tud Y O F R Elig Io Us a Nd Ethnic D Iversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand's Moment of Truth — Royal Succession After the King Passes Away.” - U.S

THAILAND’S MOMENT OF TRUTH A SECRET HISTORY OF 21ST CENTURY SIAM #THAISTORY | VERSION 1.0 | 241011 ANDREW MACGREGOR MARSHALL MAIL | TWITTER | BLOG | FACEBOOK | GOOGLE+ This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This story is dedicated to the people of Thailand and to the memory of my colleague Hiroyuki Muramoto, killed in Bangkok on April 10, 2010. Many people provided wonderful support and inspiration as I wrote it. In particular I would like to thank three whose faith and love made all the difference: my father and mother, and the brave girl who got banned from Burma. ABOUT ME I’m a freelance journalist based in Asia and writing mainly about Asian politics, human rights, political risk and media ethics. For 17 years I worked for Reuters, including long spells as correspondent in Jakarta in 1998-2000, deputy bureau chief in Bangkok in 2000-2002, Baghdad bureau chief in 2003-2005, and managing editor for the Middle East in 2006-2008. In 2008 I moved to Singapore as chief correspondent for political risk, and in late 2010 I became deputy editor for emerging and frontier Asia. I resigned in June 2011, over this story. I’ve reported from more than three dozen countries, on every continent except South America. I’ve covered conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories and East Timor; and political upheaval in Israel, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand and Burma. Of all the leading world figures I’ve interviewed, the three I most enjoyed talking to were Aung San Suu Kyi, Xanana Gusmao, and the Dalai Lama. -

Experience the Diverse Lifestyle

176 mm 7 inc 7 inc 176 mm Experience the diverse lifestyle Bangkok, the City of Angels, is full of unique cultural heritage, beautiful canals and rivers, charming hospitality, and fascinating trends. Colourful events in the streets play an important role in Thai lifestyle and add vitality to the high-rise environment. Wherever you go, there are sidewalk vendors selling just about anything; such as, handmade products, fabrics and textiles, jewellery, and food. Street food is as delicious as that provided in restaurants, ranging from barbeque skewers to fresh seafood, and even international cuisine. One of the best ways to explore Bangkok is to take a stroll along the following roads as they reflect the everyday city life of the local people. Bangkok City Printed in Thailand by Promotional Material Production Division, Marketing Services Department, Tourism Authority of Thailand for free distribution. www.tourismthailand.org E/MAR 2019 The contents of this publication are subject to change without notice. 62-02-134_A+B-Colourful Bkk new22-3_J-CoatedUV.indd 1 62-02-134_A-Colourful street Life in Bangkok new22-3_J-CC2018 Coated UV 22/3/2562 BE 18:18 176 mm 7 inc 7 inc 176 mm Experience the diverse lifestyle Bangkok, the City of Angels, is full of unique cultural heritage, beautiful canals and rivers, charming hospitality, and fascinating trends. Colourful events in the streets play an important role in Thai lifestyle and add vitality to the high-rise environment. Wherever you go, there are sidewalk vendors selling just about anything; such as, handmade products, fabrics and textiles, jewellery, and food. -

48 Hours in Bangkok: Eat, Play, Sleep What Is the Perfect Trip in Bangkok for 2 Days

48 Hours in Bangkok: Eat, Play, Sleep What is the perfect trip in Bangkok for 2 days DAY 1 Eat - Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner Breakfast Breakfast at the Royal Orchid Sheraton’s FEAST - There's something for everyone at this world Feast at Royal Orchid cuisine dining spot with an exceptional choice of breakfast options (including something Sheraton Hotel & Towers, Charoen Krung Road, for the kids). Bang Rak Get an early start on your 48 hours in Bangkok and head to Feast any time from 6:00 AM - 10:30 AM. Call +66 (0) 2266 0123 or email: [email protected] Lunch Lunch at Eat Sight Story - A real gem hidden down a tiny Bangkok alleyway, complete with river and temple views. Eat Sight Story, Tatien, Maharaj Road Eat Sight Story serve a delicious array of classic Thai and fusion cuisine...plus a cocktail menu worth exploring. Call +66 (0) 2622 2163 Dinner Early dinner or late lunch at Somtum Der - Absorb the art of authentic Som Tum (papaya salad) in this cosy and welcoming eatery. Somtum Der, Saladang, Somtum Der has a laid back outside eating area that creates a captivating eat-like-a-local vibe Silom as you tuck into some Tum Thai with fresh papaya, zesty lime and chili. Call +66 (0) 2632 4499 1 Play – Don’t Miss Out! Temple hopping Exploring the many incredibly beautiful temples in Bangkok has to be done, and the Grand Palace is top of the must-see attractions. The Grand Palace has been the ocial residence of the Kings of Siam and Thailand since the 1700’s and is also home to the temple of the Emerald Buddha. -

Thailand & Laos

THAILAND & LAOS ESSENTIAL SOUTHEAST ASIA Small Group Trip 16 Days ATJ.com | [email protected] | 800.642.2742 Page 1 Essential Southeast Asia THAILAND & LAOS SOUTHEAST ASIA ESSENTIAL SOUTHEAST ASIA Small Group Trip 16 Days LAOS Chiang Saen . Pakbeng. Chiang Rai . Luang Prabang Chiang Mai . Mekong River Lampang . Sukhothai THAILAND Ayutthaya . Khao Yai Bangkok Giant Temple Guardian Statue INDULGE YOUR BUDDHIST CULTURES, TRADITIONAL ART, TRIBAL WANDERLUST PEOPLES, RIVER CRUISE, UNIQUE CEREMONIES, LOY Ø Explore ancient cities and modern metropolises KRATHONG FESTIVAL, UNESCO SITES, NATIONAL Ø Join the locals in celebrating an authentic PARKS, WILDLIFE Thai festival This journey represents a return to our roots. Our company was built on pioneering trips Ø Learn about native elephants to Southeast Asia, as these countries were just opening up their borders, combining famous iconic sites with far-flung meanderings. This journey resurrects that spirit, embodying a masterful Ø Visit remote hill-tribe villages that still practice synthesis of iconic sights and unique, immersive, cultural experiences. traditional ways of life Venture from the modern metropolis of Bangkok deep into the countryside to witness ancient Ø Cruise among sleepy villages and colorful markets ways of life still practiced by secluded hill tribes. Visit local artists deeply invested in their crafts. in the Mekong Delta Sail deep into wilderness preserves in search of colorful wildlife and foliage. Join in a traditional festival, celebrated unbroken for centuries, and learn about Buddhist traditions directly from Ø Enjoy a special private Lao welcome ceremony and friendly monks. Soak up the colonial charm of Luang Prabang and, most of all, experience the dance performance unmatched warmth of the local people. -

9 Sacred Sites in Bangkok Temple As an Auspicious Activity That Grants Them Happiness and Good Luck

The 9 Sacred Sites Buddhists in Thailand pay homage at the temple or ‘wat’ as they believe it is a way to make merit. They consider paying homage to the principal Buddha image or to the main Chedi of the 9 Sacred Sites in Bangkok temple as an auspicious activity that grants them happiness and good luck. The number nine is considered auspicious because it is pronounced as ‘kao,’ similar to the word meaning ‘to progress’ or ‘to step forward.’ Therefore it is believed that a visit to nine sacred temples in one day gives the worshippers prosperity and good luck. The nine sacred temples in Bangkok are of significant value as they are royal temples and convenient for worshippers as they are located close to each other in the heart of Bangkok. Wat Saket Printed in Thailand by Promotional Material Production Division, Marketing Services Department, Tourism Authority of Thailand for free distribution. www.tourismthailand.org E/JUL 2017 The contents of this publication are subject to change without notice. The 9 Sacred Sites Buddhists in Thailand pay homage at the temple or ‘wat’ as they believe it is a way to make merit. They consider paying homage to the principal Buddha image or to the main Chedi of the 9 Sacred Sites in Bangkok temple as an auspicious activity that grants them happiness and good luck. The number nine is considered auspicious because it is pronounced as ‘kao,’ similar to the word meaning ‘to progress’ or ‘to step forward.’ Therefore it is believed that a visit to nine sacred temples in one day gives the worshippers prosperity and good luck. -

Incendiary Central: the Spatial Politics of the May 2010 Street Demonstrations in Bangkok Sophorntavy Vorng

Urbanities, Vol. 2 · No 1 · May 2012 © 2012 Urbanities Incendiary Central: The Spatial Politics of the May 2010 Street Demonstrations in Bangkok Sophorntavy Vorng (Independent Anthropologist, Bangkok) [email protected] In May 2010, anti-government demonstrators made a flaming inferno of the CentralWorld Plaza – Thailand’s biggest, and Asia’s second largest, shopping mall. It was the climax of the latest major chapter of the Thai political conflict, during which thousands of protestors swarmed Ratchaprasong, the commercial centre of Bangkok, in an ultimately failed attempt to oust Abhisit Vejjajiva’s regime from power. In this article, I examine how downtown Bangkok and exclusive malls like CentralWorld represent physical and cultural spaces from which the marginalized working classes have been strikingly excluded. It is a configuration of space that maps the contours of a heavily uneven distribution of power and articulates a vernacular of prestige wherein class relations are inscribed in urban space. The significance of the Red-Shirted movement’s occupation of Ratchaprasong lies in the subversion of this spatialisation of power and draws attention to the symbolic deployment of space in the struggle for political supremacy. Keywords: Bangkok, protest, space, class, politics, consumption, mall Introduction: The Burning Centre In late May 2010, billowing charcoal smoke rose from the Ratchaprasong district in central Bangkok, casting a dark pall over the sprawling city. Much of it came from the flaming inferno of the CentralWorld Plaza, Thailand’s biggest, and Southeast Asia’s second largest, shopping mall.1 What will likely become one of the most iconic images of the conflagration is a photo by Adrees Latif of Reuters featuring a huge golden head with the likeness of a female deity in a square in front of the mall, her eyes seemingly wide with surprise as a tattered Thai flag fluttered pitifully overhead and the 500.000 metre square complex blazed in the background (see Image 1). -

Centara Grand at Centralworld Contact Details

Centara Grand at CentralWorld Contact Details Property Code: CGCW Official Star Rating: 5 Address: 999/99 Rama 1 Road,Pathumwan Bangkok 10330,Thailand Telephone: (+66) 2-100-1234 Hotel Fax: (+66) 2-100-1235 E-mail: [email protected] Official Hours of Operation: 24 hours GPS Longtitude: 100.539515018463 GPS Latitude: 13.7468157419102 General Manager Tel: (+66) 2-100-1234 #6100 Administrator Tel: (+66) 2-100-1234 Reservation Tel: (+66) 2-100-1234 #1 Reception Tel: (+66) 2-100-1234 #14 Sales Tel: (+66) 2-100-1234 #6547 Google my Business URL: https://goo.gl/maps/VkGDcCXES76QzH7X6 Google my Direction URL: https://www.google.com/maps/dir//999+Centara+Grand+at+CentralWorld,+99+Rama+I+Rd,+Pathum+Wan,+Pathum+W an+District,+Bangkok+10330/@13.747717,100.5365583,17z/data=!4m8!4m7!1m0!1m5!1m1!1s0x30e2992f7809567f:0xccc050cff0e7d 234!2m2!1d100.538747!2d13.747717 Recommended For Centara Grand at CentralWorld Families Single travellers Couples and honeymooners Business travellers MICE Shoppers Young travellers Group of friends Centara Grand at CentralWorld Building Total number of building(s) 1 Building: Centara Grand & Bangkok Convention Centre at CentralWorld Building name: Centara Grand & Bangkok Convention Centre at CentralWorld Year built: 2008 Last renovated in: - How many floors: 55 How many rooms: 505 Number of keys: 512 Location: Central to the business district, Centara Grand and Bangkok Convention Centre at CentralWorld is connected to major shopping and entertainment complexes by skywalk, and offer easy access to the mass transit systems. A rapid rail link directly to and from Suvarnabhumi Airport where travellers can check-in their luggage before boarding the train is 10 minutes away from the hotel. -

Thailand's Internal Nation Branding

Petra Desatova, Nordic Institute of Asian Studies CHAPTER 4: THAILAND’S INTERNAL NATION BRANDING In commercial branding, ambassadorship is considered a crucial feature of the branding process since customers’ perceptions of a product or a service are shaped through the contact with the employees who represent the brand. Many companies thus invest heavily into internal branding to make sure that every employee ‘lives the brand’ thereby boosting their motivation and morale and creating eager brand ambassadors.1 The need for internal branding becomes even more imperative when it comes to branding nations as public support is vital for the new nation brand to succeed. Without it, nation branding might easily backfire. For example, the Ukrainian government was forced to abandon certain elements of its new nation brand following fierce public backlash.2 The importance of domestic support, however, goes beyond creating a favourable public opinion on the new nation brand. As Aronczyk points out, the nation’s citizens need to ‘perform attitudes and behaviours that are compatible with the brand strategy’ should this strategy succeed. This is especially the case when the new nation brand does not fully reflect the reality on the ground as nation branding often produces an airbrushed version rather than a truthful reflection of the nation, its people, and socio-political and economic conditions. Although some scholars are deeply sceptical about governments’ ability to change citizens’ attitudes and behaviours through nation branding, we should not ignore such attempts.3 This chapter examines Thailand’s post-coup internal nation branding efforts in the education, culture, public relations and private sectors: what were the political motivations behind these efforts? I argue that the NCPO was using internally focused nation branding to diffuse virtue across Thai society in preparation for the post-Bhumibol era. -

Thailands Beaches and Islands

EYEWITNESS TRAVEL THAILAND’S BEACHES & ISLANDS BEACHES • WATER SPORTS RAINFORESTS • TEMPLES FESTIVALS • WILDLIFE SCUBA DIVING • NATIONAL PARKS MARKETS • RESTAURANTS • HOTELS THE GUIDES THAT SHOW YOU WHAT OTHERS ONLY TELL YOU EYEWITNESS TRAVEL THAILAND’S BEACHES AND ISLANDS EYEWITNESS TRAVEL THAILAND’S BEACHES AND ISLANDS MANAGING EDITOR Aruna Ghose SENIOR EDITORIAL MANAGER Savitha Kumar SENIOR DESIGN MANAGER Priyanka Thakur PROJECT DESIGNER Amisha Gupta EDITORS Smita Khanna Bajaj, Diya Kohli DESIGNER Shruti Bahl SENIOR CARTOGRAPHER Suresh Kumar Longtail tour boats at idyllic Hat CARTOGRAPHER Jasneet Arora Tham Phra Nang, Krabi DTP DESIGNERS Azeem Siddique, Rakesh Pal SENIOR PICTURE RESEARCH COORDINATOR Taiyaba Khatoon PICTURE RESEARCHER Sumita Khatwani CONTRIBUTORS Andrew Forbes, David Henley, Peter Holmshaw CONTENTS PHOTOGRAPHER David Henley HOW TO USE THIS ILLUSTRATORS Surat Kumar Mantoo, Arun Pottirayil GUIDE 6 Reproduced in Singapore by Colourscan Printed and bound by L. Rex Printing Company Limited, China First American Edition, 2010 INTRODUCING 10 11 12 13 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 THAILAND’S Published in the United States by Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Inc., BEACHES AND 375 Hudson Street, New York 10014 ISLANDS Copyright © 2010, Dorling Kindersley Limited, London A Penguin Company DISCOVERING ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNDER INTERNATIONAL AND PAN-AMERICAN COPYRIGHT CONVENTIONS. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED, STORED IN THAILAND’S BEACHES A RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, AND ISLANDS 10 ELECTRONIC, MECHANICAL, PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING OR OTHERWISE WITHOUT THE PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER. Published in Great Britain by Dorling Kindersley Limited. PUTTING THAILAND’S A CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION RECORD IS BEACHES AND ISLANDS AVAILABLE FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS. -

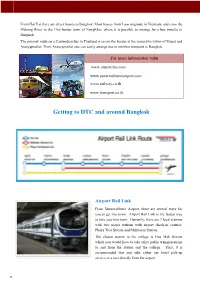

Getting to DTC and Around Bangkok

From Hat Yai there are direct busses to Bangkok. Most busses from Laos originate in Vientiane and cross the Mekong River to the Thai border town of NongKhai, where it is possible to arrange for a bus transfer to Bangkok. The primary route on a Cambodian bus to Thailand is across the border at the respective towns of Poipet and Aranyaprathet. From Aranyaprathet one can easily arrange bus or minibus transport to Bangkok. For more information visit: www.airportthai.com www.suvarnabhumiairport.com www.railway.co.th www.transport.co.th Getting to DTC and around Bangkok Airport Rail Link From Suvarnabhumi Airport, there are several ways for you to get into town. Airport Rail Link is the fastest way to take you into town. Currently, there are 7 local stations with two major stations with airport check-in counter: Phaya Thai Station and Makkasan Station. The closest station to the college is Hua Mak Station which you would have to take other public transportations to and from the station and the college. Thus, it is recommended that you take either our hotel pick-up service or a taxi directly from the airport. 8 Taxi All 30,000+ taxis cruising Bangkok city streets are metered and are required by law to use them. If a taxi offers you a fixed-price fare, politely ask to use the meter. If not, then flag down another taxi. In general, parked taxis will ask for fixed fares while those already driving will generally use the meter. Taxis using the meter charge a minimum of 35 baht for the first 3 kilometers. -

A Bangkok Mice Venue

A BANGKOK MICE VENUE YOUR VISUAL DISCOVERY STARTS AT www.centarahotelsresorts.com/cgcw/tour.asp WELCOME TO BANGKOK’S HEART THE TALK OF THE TOWN Centara Grand at CentralWorld majestically soars above the centre of Bangkok’s bustling business and shopping districts at Ratchaprasong. The hotel raises the bar for a five-star luxury accommodation and dining to new heights of excellence. The hotel was designed to resemble a flowering lotus and its theme incorporates life’s four elements - earth, air, fire, and water. The hotel has many remarkable features, including: a total of 59 floors that soar 235 meters (771 ft) into the sky; located in the most central point in Bangkok that provides easy all-around access to the city; a few minutes away and connected via skywalk to the Chidlom and Siam BTS Sky Train Stations; and located 27 kilometres from Suvarnabhumi Airport or about a 45 minute drive under normal traffic conditions. LAVISH ACCOMMODATIONS Behind the hotel’s meticulously crafted edifice lies a state-of-the-art, millennium-inspired five-star, uptown city-centre hotel with 505 luxury room, including 36 suites and 9 World Executive Club floors. Each room boasts individually controlled air-conditioning, bathroom with large tub and shower, and beautifully furnished, including a specially designed bed. The rooms also excel on the tech side with easily operated control panels for the lighting and other functions, along with Wi-Fi high-speed internet, flat-screen smart TVs, in-house music, and direct international telephone dialling. Additionally, the rooms have a well-stocked minibar/refrigerator and personal in-room safety box big enough to fit a standard sized laptop. -

Grand Palace, Wat Arun, the Temple of Dawn

GREEN TRAVEL SERVICE CO., LTD. TAT LICENSE NO. 12/0267 SELLING PRICE : ADULT 2,100 BAHT / CHILD (4 - 10 YEARS) 1,400 BAHT Ayutthaya Full Day Package Tour (06.30 – 16.30 hrs.)Round Trip ( Bus - Boat ) Visit “Thailand’s World Heritage Ancient City” By bus: 06:30 hrs. Pick up at your hotel. 07:00 hrs. Check in at River City Shopping Complex – Sipraya. 07:30 hrs. Depart from Bangkok by Air - conditioned Coach to Ayutthaya Province. 08:30 hrs. Arrive BANG PA-IN SUMMER PALACE, The Palace of King Rama V with its mixture of Thai, Chinese and Gothic Architecture. 10:30 hrs. Arrive Ayutthaya The world heritage ancient city. Former Capital City of Thailand (B.E.1350-1767). Ayutthaya has been included in UNESCO list of World heritage since December 13, 1991. Visit to WAT MAHATHAT, The royal monastery and served as the residence of the supreme monk. Visit to WAT PHRA SRI SANPHET, The largest, most important and beautiful within the Royal Palace compound in Ayutthaya like the temple of The Emerald Buddha in Bangkok. Visit to VIHARA PHRA MONGKHON BOPHIT, located in the south of WAT PHRA SRI SANPHET. By cruise: 13:00 hrs. Welcome on Board the Grand Pearl Cruiser at WAT CHONG LOM (Nonthaburi). for cruising to Bangkok along the Chao Praya River. Superb buffet lunch which includes a delight variety of oriental and western cuisines will be served. The boat will pass Nonthaburi Province, Koh Kret “The monn community ”, The Royal Barges, Thammasart University, The Royal Grand Palace, Wat Arun, The Temple of Dawn 15:00 hrs.