Thailand's Internal Nation Branding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experience the Diverse Lifestyle

176 mm 7 inc 7 inc 176 mm Experience the diverse lifestyle Bangkok, the City of Angels, is full of unique cultural heritage, beautiful canals and rivers, charming hospitality, and fascinating trends. Colourful events in the streets play an important role in Thai lifestyle and add vitality to the high-rise environment. Wherever you go, there are sidewalk vendors selling just about anything; such as, handmade products, fabrics and textiles, jewellery, and food. Street food is as delicious as that provided in restaurants, ranging from barbeque skewers to fresh seafood, and even international cuisine. One of the best ways to explore Bangkok is to take a stroll along the following roads as they reflect the everyday city life of the local people. Bangkok City Printed in Thailand by Promotional Material Production Division, Marketing Services Department, Tourism Authority of Thailand for free distribution. www.tourismthailand.org E/MAR 2019 The contents of this publication are subject to change without notice. 62-02-134_A+B-Colourful Bkk new22-3_J-CoatedUV.indd 1 62-02-134_A-Colourful street Life in Bangkok new22-3_J-CC2018 Coated UV 22/3/2562 BE 18:18 176 mm 7 inc 7 inc 176 mm Experience the diverse lifestyle Bangkok, the City of Angels, is full of unique cultural heritage, beautiful canals and rivers, charming hospitality, and fascinating trends. Colourful events in the streets play an important role in Thai lifestyle and add vitality to the high-rise environment. Wherever you go, there are sidewalk vendors selling just about anything; such as, handmade products, fabrics and textiles, jewellery, and food. -

Incendiary Central: the Spatial Politics of the May 2010 Street Demonstrations in Bangkok Sophorntavy Vorng

Urbanities, Vol. 2 · No 1 · May 2012 © 2012 Urbanities Incendiary Central: The Spatial Politics of the May 2010 Street Demonstrations in Bangkok Sophorntavy Vorng (Independent Anthropologist, Bangkok) [email protected] In May 2010, anti-government demonstrators made a flaming inferno of the CentralWorld Plaza – Thailand’s biggest, and Asia’s second largest, shopping mall. It was the climax of the latest major chapter of the Thai political conflict, during which thousands of protestors swarmed Ratchaprasong, the commercial centre of Bangkok, in an ultimately failed attempt to oust Abhisit Vejjajiva’s regime from power. In this article, I examine how downtown Bangkok and exclusive malls like CentralWorld represent physical and cultural spaces from which the marginalized working classes have been strikingly excluded. It is a configuration of space that maps the contours of a heavily uneven distribution of power and articulates a vernacular of prestige wherein class relations are inscribed in urban space. The significance of the Red-Shirted movement’s occupation of Ratchaprasong lies in the subversion of this spatialisation of power and draws attention to the symbolic deployment of space in the struggle for political supremacy. Keywords: Bangkok, protest, space, class, politics, consumption, mall Introduction: The Burning Centre In late May 2010, billowing charcoal smoke rose from the Ratchaprasong district in central Bangkok, casting a dark pall over the sprawling city. Much of it came from the flaming inferno of the CentralWorld Plaza, Thailand’s biggest, and Southeast Asia’s second largest, shopping mall.1 What will likely become one of the most iconic images of the conflagration is a photo by Adrees Latif of Reuters featuring a huge golden head with the likeness of a female deity in a square in front of the mall, her eyes seemingly wide with surprise as a tattered Thai flag fluttered pitifully overhead and the 500.000 metre square complex blazed in the background (see Image 1). -

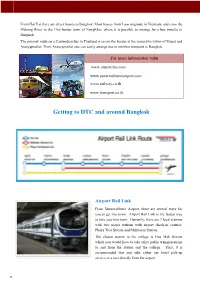

Getting to DTC and Around Bangkok

From Hat Yai there are direct busses to Bangkok. Most busses from Laos originate in Vientiane and cross the Mekong River to the Thai border town of NongKhai, where it is possible to arrange for a bus transfer to Bangkok. The primary route on a Cambodian bus to Thailand is across the border at the respective towns of Poipet and Aranyaprathet. From Aranyaprathet one can easily arrange bus or minibus transport to Bangkok. For more information visit: www.airportthai.com www.suvarnabhumiairport.com www.railway.co.th www.transport.co.th Getting to DTC and around Bangkok Airport Rail Link From Suvarnabhumi Airport, there are several ways for you to get into town. Airport Rail Link is the fastest way to take you into town. Currently, there are 7 local stations with two major stations with airport check-in counter: Phaya Thai Station and Makkasan Station. The closest station to the college is Hua Mak Station which you would have to take other public transportations to and from the station and the college. Thus, it is recommended that you take either our hotel pick-up service or a taxi directly from the airport. 8 Taxi All 30,000+ taxis cruising Bangkok city streets are metered and are required by law to use them. If a taxi offers you a fixed-price fare, politely ask to use the meter. If not, then flag down another taxi. In general, parked taxis will ask for fixed fares while those already driving will generally use the meter. Taxis using the meter charge a minimum of 35 baht for the first 3 kilometers. -

A Bangkok Mice Venue

A BANGKOK MICE VENUE YOUR VISUAL DISCOVERY STARTS AT www.centarahotelsresorts.com/cgcw/tour.asp WELCOME TO BANGKOK’S HEART THE TALK OF THE TOWN Centara Grand at CentralWorld majestically soars above the centre of Bangkok’s bustling business and shopping districts at Ratchaprasong. The hotel raises the bar for a five-star luxury accommodation and dining to new heights of excellence. The hotel was designed to resemble a flowering lotus and its theme incorporates life’s four elements - earth, air, fire, and water. The hotel has many remarkable features, including: a total of 59 floors that soar 235 meters (771 ft) into the sky; located in the most central point in Bangkok that provides easy all-around access to the city; a few minutes away and connected via skywalk to the Chidlom and Siam BTS Sky Train Stations; and located 27 kilometres from Suvarnabhumi Airport or about a 45 minute drive under normal traffic conditions. LAVISH ACCOMMODATIONS Behind the hotel’s meticulously crafted edifice lies a state-of-the-art, millennium-inspired five-star, uptown city-centre hotel with 505 luxury room, including 36 suites and 9 World Executive Club floors. Each room boasts individually controlled air-conditioning, bathroom with large tub and shower, and beautifully furnished, including a specially designed bed. The rooms also excel on the tech side with easily operated control panels for the lighting and other functions, along with Wi-Fi high-speed internet, flat-screen smart TVs, in-house music, and direct international telephone dialling. Additionally, the rooms have a well-stocked minibar/refrigerator and personal in-room safety box big enough to fit a standard sized laptop. -

Shopping in Thailand

Siam International Legal Group | Thailand´s Largest Legal Network Service Shopping in Thailand Thailand, particularly Bangkok, is definitely a paradise for all shopaholics.The massive, modern, multi-storey shopping malls provide a myriad of choices for every budget and need. The only problem you must face is deciding where to go first because of the infinite shopping possibilities! But with a map and a dose of style-savvy, you are good to go! Thailand is renowned all over the world for its beautiful silk, jewelry and original exquisite handicrafts. It is also known for producing first-class fake goods. From the most luxurious to the cheapest—clothing, shoes, bags, apparels, jewelry, to branded luxury goods and even electronic devices such as mobile phones and laptop computers, you can find almost anything of your fancy here. In Bangkok, you can choose among a wide variety of Shopping malls and open-air markets. Like other big cities, shopping malls & department stores are places where you can but high quality products. Though there are also some shops and stalls in shopping centers where you can haggle for the discounted price, bargain hunters will be enjoying shopping in Thai markets for the most affordable goods. Shopping malls like Gaysorn, Siam Paragon, & Emporium are popular for tourists looking for international brands and world’s top quality designer wear. They are mostly open from 10am-10pm daily. These shopping centers are very accessible via (BTS), the city’s most efficient modern sky train. GAYSORN Business Hours: 10:00 - 20:00 Location: Ratchaprasong Junction BTS: Chitlom SIAM PARAGON Business Hours: 10:00 - 22:00 Location: Next to Siam Centre, Pathumwan BTS: Siam Tip: Tourist can apply for a ‘Tourist Discount Card’ on the information desk for a 5% discount on most purchases. -

Bangkok Travel Guide

Bangkok Travel Guide Bangkok Information .......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Currency ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Weather ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Language and Communication ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommended dishes .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Transportation .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 MRT ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 BTS ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 TAXI .......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

AW Fact Sheet the Market Bangkok ENG

EVERYDAY MARKET“ “ for EVERYONE’S LIFESTYLE The Newest Shopping Destination in The Market Bangkok Ratchaprasong Bangkok Downtown. The mall will not only gather merchandises exclusively from all well-known markets around Bangkok but will also harmoniously combine Thai market experiences through distinctive and remarkable architecture. Proudly presenting the legend of Bangkokian folkways, this unique and charming concept will definitely deliver visitors’ expectation and satisfaction of both local Thais and foreigners. The Market Bangkok will impeccably supplement Ratchaprasong to be one of the World Class Shopping Districts in no time. Project Information Developer The Platinum Market Co., Ltd. (A Member of The Platinum Group PLC.) Location Ratchadamri Road, Bangkok Accessibility 3 Main Roads : Ratchadamri, Petchaburi and Chitlom Pratunam Pier, Chitlom BTS Station, R-Walk Skywalk Gross Leasable Area Approx. 40,000 sq.m. Makkasan Airport Rail Link Station (300 m away) Parking Space Approx. 2,000 Cars Land Area Approx. 20 Rais Number of Floor 6 Floors (Shopping Center) Project Type Mixed-Use Development : Shopping Center, Merchandising Mix Food & Beverage Hotels and Oce Building Fashion & Accessories Target Tourists and Local Thais, Including Oce Workers, Students, Souvenir, Decorative items Friends and Family with Medium Class Income (B-C) Specialty Stores Gross Building Approx. 200,000 sq.m. Banks Area Wellness & Vitality Expected Completion Q4 of 2018 (Shopping Center) Time Location Map BAIYOKE SKY RATCHAPRAROP LEMONTEA INDRA SQUARE CENTARA WATERGATE NIKOM MAKKASAN RD. ASIA HOTEL WATERGATE PHETCHABURI RD. KRUNGTONG PAVILLION PLAZA RATCHATHEWI SHIBUYA BERKELEY AMARI PRATUNAM CITY WATERGATE VIE COMPLEX PALLADIUM TALAD NEON HOTEL THANACHART EVERGREEN THE PLATINUM BANK PANTIP PLAZA EXPRESSWAY PLACE FASHION MALL GRAND NOVOTEL MANHATTAN DIAMOND BANGKOK CHIDLOM PHETCHABURI RD. -

The System Map of Bangkok Rail Transit Network

The System Map of N Northbound 5 0 Railroad to 0 th 2 Bangkok Rail TransitLa stN Updeate:t 9w Janouaryr 2k005 LINES DESTINATIONS h Chiang Mai c t Nakhon Ratchasima BTS – “Skytrain” Park & ride station a w Pathum Thani Nong Khai o Light green Phran Nok – Samut Prakan City airport terminal o Ubon Ratchathani Lam Lukka Z Dark green Saphan Mai – Bang Wa Provincial bus terminal MRT – “Metro” Connection with the State Railway Rang Sit Blue City loop with Tha Phra – Bang Khae Connection with the Chao Phraya Express Boat Muang Ek Royal Thai Air Force Academy Purple Bang Yai – Rat Burana BRT Connection with the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Orange Bang Kapi – Bang Bamru Landmark within walking distance K Don Muang Bhumibol Hospital S h K a l Yellow Lat Phrao – Sri Nagarindra Interchange station(s) h m o B l n a o T Y g n Thung Song Hong Saphan Mai n a a B SRT Projects Proposed station reserved for future development g l e B g a a k a B n B t n u g to Pak Kret via Th. Chaeng Watthana MONORAIL MONORAIL to Min Buri via Th. Ram Indra a B B g a Red Rang Sit – Maha Chai Connection with provincial bus terminal n a a P R Lak Si Bang Khen g n n T S n g h h a T a i P g r k h h Y a o Y i t Pink Taling Chan – Suvarnabhumi Airport Transport Centres h Y e n a M o a a a g a I Y i i i k i t a Chit Chon n Bang Bua o Light Pink Makkasan – Suvarnabhumi Makkasan h a non-stop airport express Th. -

Why Are the Border Patrol Police in Bangkok Now?

ISSUE: 2020 No. 133 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 23 November 2020 Why are the Border Patrol Police in Bangkok now? Sinae Hyun* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Thailand’s Border Patrol Police (BPP) have been deployed at key protest sites in Bangkok since September. • The BPP had been called in to operate in Bangkok on two previous occasions: on 6 October 1976, during demonstrations at Thammasat University, and in January-May 2010, during Red Shirt unrest. • The current mobilization of the BPP in Bangkok invokes traumatic memories of the 6 October 1976 massacre. • The BPP have been Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn’s right-hand force since the early 1980s, and their civic action work has been closely tied to her royal projects. In contrast, the current monarch has limited influence over this police organization. • Significantly, the ongoing pro-democracy protests led by the young activists are an endeavor to overcome Thailand’s traumatic past. *Sinae Hyun is Research Professor, Institute for East Asian Studies, Sogang University, Seoul. 1 ISSUE: 2020 No. 133 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION On 21 June 2020, a noose was found in a garage used by Bubba Wallace, the only black driver in NASCAR’s top racing series. The discovery came days after the driver had posted a “Black Lives Matter” (BLM) message and congratulated NASCAR for its ban on displays of the Confederate battle flag. Both NASCAR and the FBI investigated the incident, and just two days later the FBI concluded that the incident was not a hate crime. It stated that “the garage door pull rope fashioned like a noose had been positioned there since as early as last fall.”1 The rope fashioned like a noose may not have been evidence of hate crime, and Bubba Wallace had to fight battle charges that he was overreacting to the discovery of the noose. -

Download Fact Sheet

DISCOVER THE HEARTBEAT OF BANGKOK THROUGH LUXURIOUS AUTHENTICITY. In the heart of one of the world’s most enigmatic capital cities, Anantara Siam Bangkok Hotel offers new explorers a luxurious retreat to enjoy life’s finer pleasures and intriguing, original journeys. Opening Date: 15 April 1983 Address: 155 Rajadamri Road, Bangkok 10330 Thailand Telephone: +66 (0) 2126 8866 Facsimile: +66 (0) 2253 9195 Central Reservations: +66 (0) 2365 9110 Central Reservations Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web Address: anantara.com/en/siam-bangkok LOCATION Anantara Siam Bangkok is located in the most central area of Bangkok and offers easy access for exploring everything Bangkok has to offer, whether you’re staying with us for business, shopping, cultural sightseeing or a cruise on the Chao Phraya River. Located in the heart of the Ratchaprasong shopping and entertainment district, our luxury urban retreat is located directly next to the sky train station at BTS Ratchadamri connecting you to the entire city with ease. Bangkok’s best shopping and Lumpini Park is located 2 minutes away. Management: Anantara Hotels, Resorts & Spas Ownership: Rajadamri Hotel Public Company Limited General Manager: Mark O’Sullivan [email protected] Director of Sales: Rajat Bhatia [email protected] Director of Marketing Mai Anh Thi Du Communications: [email protected] Director of Public Relations: Nannadda Supakdhanasombat [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Our 354 renovated rooms and suites provide a welcoming ambience that blends traditional Thai and contemporary design, refined by authentic artifacts, teak furnishings and silk fabrics. Offering luxurious city living, plush comforts are enjoyed with views over tropical gardens, the pool or the private golf course of the Royal Bangkok Sports Club. -

King Power's Five-Year Expansion Plans

King Power’s five-year expansion plans By Rebecca Byrne on April, 4 2017 | Retailers Thailand’s largest duty free operator, King Power Group, plans to spend 10 billion baht (US$290.4 million) on expanding its business over the next five years. CEO Aiyawatt Srivaddhanaprabha says the budget will be used to open five branches in Thailand and overseas, bringing the company’s total to 14 by 2021. The stores are planned for downtown in major tourist destinations with Chiang Mai being a possibility. Overseas the group is looking at duty-free options at airports such as Myanmar and the Philippines. At home, King Power bid for a duty free ship concession at U-Tapao International Airport, which serves Pattaya and Rayong, and for a new license to run a duty-free shop at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi airport when its current license expires in 2020. Srivaddhanaprabha was quoted in local media as saying that “King Power is set to become a top-five duty-free chain within five years.” He added that expansion both overseas and domestically will help grow sales by 20 per cent to reach 130 to 140 billion baht in five years, on a par with leading duty- free brands in the US. The company is the world’s seventh-largest duty-free chain, and is aiming for sales of THB92 billion this year. It will allocate THB400-500 million to promote its business, and has already set aside THB100 million to place its logo on three Thai AirAsia (TAA) jets and put advertising inside more than 40 TAA aircraft. -

Airports of Thailand Plc. Corporate Presentation – FY2008 (October 2007 – September 2008)

Airports of Thailand Plc. Corporate Presentation – FY2008 (October 2007 – September 2008) Investor Relations Center, Email: [email protected], Tel: (662) 535-5900, Fax (662) 535-5909 Disclaimer This presentation is intended to assist investors to better understanding the company’s business and financial status. This presentation may contain forward looking statements relate to analysis and other information which are based on forecast of future results and estimates of amounts not yet determinable. These statements reflect our current views with respect to future events which relate to our future prospects, developments and business strategies and are not guarantee of future performance. Such forward looking statements involve know and unknown risks and uncertainties. The Actual result may differ materially from information contained in these statements. 1 Airports in Thailand Total of 38 airports CHIANG RAI INTERNATIONAL CHIANG MAI AIRPORT INTERNATIONAL Airports of Thailand Public Company Limited * AIRPORT . 2 in Bangkok and perimeter Pai Mae Hong Son o Suvarnabhumi Airport (BKK) Nan Lampang o Don Muang International Airport (DMK) Phrae Udon Thani . 4 international airports at regional sites Sukhothai Nakhon Phanom Tak Loei Mae Sot Sakon Nakhorn o Chiang Rai International Airport (CEI) Phitsanulok Khon Kaen Phetchabun o Chiang Mai International Airport (CNX) Roi Et o Phuket International Airport (HKT) Buri Ram Surin DON MUANG Ubon Ratchathani o Hat Yai International Airport (HDY) INTERNATIONAL Nakhon Ratchasima AIRPORT SUVARNABHUMI AIRPORT AOT Airports Department of Civil Aviation (DCA) U-Tapao Hua Hin DCA Airports o 28 regional airports Trad Bangkok Airways Airports Chumpon Royal Thai Navy Ranong Royal Thai Navy Airport o U-Tapao Airport Surattani Samui HAT YAI Nakhon Si Thammarat Bangkok Airways Company INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT o Sukhothai Airport Krabi PHUKET o Samui Airport INTERNATIONAL Trang Pattani o Trad Airport AIRPORT Narathiwat * Note: AOT’s traffics account for more than 90% of Thailand’s air traffics.