Groundwater Quality: Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village Tract of Mandalay Region !

!. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. Myanmar Information Management Unit !. !. !. Village Tract of Mandalay Region !. !. !. !. 95° E 96° E Tigyaing !. !. !. / !. !. Inn Net Maing Daing Ta Gaung Taung Takaung Reserved Forest !. Reserved Forest Kyauk Aing Mabein !. !. !. !. Ma Gyi Kone Reserved !. Forest Thabeikkyin !. !. Reserved Forest !. Let Pan Kyunhla Kone !. Se Zin Kone !. Kyar Hnyat !. !. Kanbalu War Yon Kone !. !. !. Pauk Ta Pin Twin Nge Mongmit Kyauk Hpyu !. !. !. Kyauk Hpyar Yae Nyar U !. Kyauk Gyi Kyet Na !. Reserved Hpa Sa Bai Na Go Forest Bar Nat Li Shaw Kyauk Pon 23° N 23° Kyauk War N 23° Kyauk Gyi Li Shaw Ohn Dan Lel U !. Chaung Gyi !. Pein Pyit !. Kin Tha Dut !. Gway Pin Hmaw Kyauk Sin Sho !. Taze !. !. Than Lwin Taung Dun Taung Ah Shey Bawt Lone Gyi Pyaung Pyin !. Mogoke Kyauk Ka Paing Ka Thea Urban !. Hle Bee Shwe Ho Weik Win Ka Bar Nyaung Mogoke Ba Mun !. Pin Thabeikkyin Kyat Pyin !. War Yae Aye !. Hpyu Taung Hpyu Yaung Nyaung Nyaung Urban Htauk Kyauk Pin Ta Lone Pin Thar Tha Ohn Zone Laung Zin Pyay Lwe Ngin Monglon !. Ye-U Khin-U !. !. !. !. !. Reserved Forest Shwe Kyin !. !. Tabayin !. !. !. !. Shauk !. Pin Yoe Reserved !. Kyauk Myaung Nga Forest SAGAING !. Pyin Inn War Nat Taung Shwebo Yon !. Khu Lel Kone Mar Le REGION Singu Let Pan Hla !. Urban !. Koke Ko Singu Shwe Hlay Min !. Kyaung !. Seik Khet Thin Ngwe Taung MANDALAY Se Gyi !. Se Thei Nyaung Wun Taung Let Pan Kyar U Yin REGION Yae Taw Inn Kani Kone Thar !. !. Yar Shwe Pyi Wa Di Shwe Done !. Mya Sein Sin Htone Thay Gyi Shwe SHAN Budalin Hin Gon Taing Kha Tet !. Thar Nyaung Pin Chin Hpo Zee Pin Lel Wetlet Kyun Inn !. -

TRENDS in MANDALAY Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY Photo credits Paul van Hoof Mithulina Chatterjee Myanmar Survey Research The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY UNDP MYANMAR Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 11 2. Methodology 14 2.1 Objectives 15 2.2 Research tools 15 3. Introduction to Mandalay region and participating townships 18 3.1 Socio-economic context 20 3.2 Demographics 22 3.3 Historical context 23 3.4 Governance institutions 26 3.5 Introduction to the three townships participating in the mapping 33 4. Governance at the frontline: Participation in planning, responsiveness for local service provision and accountability 38 4.1 Recent developments in Mandalay region from a citizen’s perspective 39 4.1.1 Citizens views on improvements in their village tract or ward 39 4.1.2 Citizens views on challenges in their village tract or ward 40 4.1.3 Perceptions on safety and security in Mandalay Region 43 4.2 Development planning and citizen participation 46 4.2.1 Planning, implementation and monitoring of development fund projects 48 4.2.2 Participation of citizens in decision-making regarding the utilisation of the development funds 52 4.3 Access to services 58 4.3.1 Basic healthcare service 62 4.3.2 Primary education 74 4.3.3 Drinking water 83 4.4 Information, transparency and accountability 94 4.4.1 Aspects of institutional and social accountability 95 4.4.2 Transparency and access to information 102 4.4.3 Civil society’s role in enhancing transparency and accountability 106 5. -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

Weekly Security Review

The information in this report is correct as of 8.00 hours (UTC+6:30) 22 July 2020. Weekly Security Review Safety and Security Highlights for Clients Operating in Myanmar Dates covered: 16 July – 22 July 2020 The contents of this report are subject to copyright and must not be reproduced or shared without approval from EXERA. The information in this report is intended to inform and advise; any mitigation implemented as a result of this information is the responsibility of the client. Questions or requests for further information can be directed to [email protected]. COMMERCIAL-IN-CONFIDENCE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 COVID -19 PANDEMIC 3 INTERNAL CONFLICT 3 MYANMAR GENERAL ELECTIONS 3 INTERNAL CONFLICT 4 MAIN INCIDENTS 4 RAKHINE STATE 4 SHAN STATE 6 KAYIN STATE 6 ANALYSIS AND COMMENT 6 NATIONWIDE 6 RAKHINE STATE 6 SHAN STATE 7 KAYIN STATE 8 ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 8 ELECTION WATCH 9 TRANSPORTATION 12 MAIN INCIDENTS 12 COMMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 12 CRIME AND ACCIDENTS 14 MAIN INCIDENTS 14 COMMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 15 TRAFFICKING 15 MAIN INCIDENTS 15 COMMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 15 ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS 17 EARTHQUAKES 17 MAIN INCIDENTS 17 COMMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 FIRE BREAKOUTS 18 MAIN INCIDENTS 18 COMMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 HEALTH HAZARDS 18 CURRENT SITUATION 18 COMMENTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 22 GLOSSARY OF TERMS 24 ANNEX: DRUGS SEIZURES IN MYANMAR FROM 14 TO 22 JULY 2020 26 2 of 26 COMMERCIAL-IN-CONFIDENCE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Covid -19 pandemic When EXERA released its latest Weekly Security Review (WSR), the figure for 15 July at 08:00 hrs was 337 confirmed cases since the beginning of the epidemic, i.e. -

Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma

To: Hon. Mr. Ban Ki-moon Secretary-General United Nations From: Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma CC: Mr. B. Lynn Pascoe, Under-Secretary-General, United Nations Mr. Ibrahim Gambari, Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser to the Secretary- General on Myanmar/Burma Permanent Representatives to the United Nations of the five Permanent Members (China, Russia, France, United Kingdom and the United states) of the UN Security Council U Aung Shwe, Chairman, National League for Democracy Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, General Secretary, National League for Democracy U Aye Thar Aung, Secretary, Committee Representing the Peoples' Parliament (CRPP) Veteran Politicians The 88 Generation Students Date: 1 August 2007 Re: National Reconciliation and Democratization in Myanmar/Burma Dear Excellency, We note that you have issued a statement on 18 July 2007, in which you urged the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) (the ruling military government of Myanmar/Burma) to "seize this opportunity to ensure that this and subsequent steps in Myanmar's political roadmap are as inclusive, participatory and transparent as possible, with a view to allowing all the relevant parties to Myanmar's national reconciliation process to fully contribute to defining their country's future."1 We thank you for your strong and personal involvement in Myanmar/Burma and we expect that your good offices mandate to facilitating national reconciliation in Myanmar/Burma would be successful. We, Members of Parliament elected by the people of Myanmar/Burma in the 1990 general elections, also would like to assure you that we will fully cooperate with your good offices and the United Nations in our effort to solve problems in Myanmar/Burma peacefully through a meaningful, inclusive and transparent dialogue. -

Health Facilities in Kyaukse Township - Mandalay

Myanmar Information Management Unit (! Health Facilities in Kyaukse Township - Mandalay 96°0'E 96°10'E 96°20'E 96°30'E 96°40'E PATHEINGYI 21°50'N 21°50'N AMARAPURA Kone Thar (190641) (Ohn Kyaw) Ü ! Ohn Kyaw (190639) (Ohn Kyaw) ! Za Yit Khe (190644) He Lel (190642) (Za Yit Khe) (Ohn Kyaw) ! ! Tha Man Thar (190638) ! (Tha Yet Pin) v® PYINOOLWIN Sintgaing (! SINTGAING Tha Yet Pin (190637) ! (Tha Yet Pin) v® v®! Ye (190636) (Ye) ! Shar Pin (190439) v® Kyaung (190645) (Shar Pin) ! (Kyaung) 21°40'N 21°40'N Let Pan (190474) Ngar Oe (190468) (Let Pan) (Ngar Oe) ! ! Kyaung (190472) Kyaung Kone (190473) Tha Pyay Wun (218235) ! Ywar Nan (190469) (Taung Nauk) (Taung Nauk) (Ye Baw Gyi) (Ywar Nan) ! ! ! Taung Hlwea (190491) Nyaung Pin Zauk (190455) Ngar Su (190441) Yae Twin Pyayt (190466) ! (Thin Taung) (Ngar Su) (Kyaung Pan Kone) ! Dway Hla (190440) ! ! (Thin Boke) ! (Dway Hla) ! ! v® ! Thin Taung (190490) v® Kyaung Pan Kone (190454) Taung Nauk (190470) (Thin Taung) ! Ah Shey Nge Toe (190495) Ywar Taw (190445) (Kyaung Pan Kone) (Taung Nauk) ! Ye Baw Lay (190499) Nyaung Shwe (190456) Ta Dar U Lay (190467) (Ah Shey Nge Toe) (Ye Baw Gyi) (Kyee Eik) Zay Kone (190465) ! v® Ye Baw Gyi (190498) ! (Nyaung Shwe) (Thin Boke) Shwe Dar (190496) (Ye Baw Gyi) ! ! (Thin Boke) ! Nyaung Wun (190457) Shwe Lay (190489) !(Shwe Dar) (Nyaung Wun) ! (In Daing) Kyee Eik (190443) ! Thin Pyo (190442) ! Thin Boke (190464) (Kyee Eik) Pa Daung Khar (190459) (Thin Pyo) (Thin Boke) KYAUKSE ! (Nyaung Wun) ! In Daing (190488) Thar Si (190497) ! ! Htan Zin Taw (190492) (Shwe Dar) -

Myanmar Traditional Egg-Tapping Game in Ayemyawady Quarter, Sagaing

Myanmar Traditional Egg-Tapping Game in Ayemyawady Quarter, Sagaing Thandar Swe * Abstract Myanmar has a long history of art, literature and music. Cultural festivals are held throughout the year in various places in various seasons. This paper presents the information of the festival of Egg-Tapping Game that has been held every year at Zinamanaung Bronze Buddha in Ayemyawady Quarter, Sagaing. Through the studies of traditional festivals, the culture of Myanmar can be seen. This festival makes friendship, unity, equality of gives and takes, and happiness for them. This paper also intends to encourage the new generations to maintain the tradition of cultural festivals. Studies for this paper are done using reference books and also through field research. Key words: Egg-Tapping Game, Ayemyawady , Sagaing. Introduction Sagaing Township is located within latitudes 21 13N and 21 15N and between longitudes 95 3´ E and 96 36´ E. It falls within the dry zone. It is situated in north of Yangon, 373 miles by road and 398 miles by rail 586 miles by water. Sagaing Township stands 228.009 feet above sea level. Sagaing Township is bounded by Mandalay Township on the east, Tada-U Township on the south, Myinmu Township on the west and Wetlet Township on the north. On the east and west the Ayeyarwady River forms a natural boundary of Sagaing Township and the Mu River forms a natural boundary on the west. On the north is the land boundary between Sagaing and Wetlet townships. The area of Sagaing Township is 485.16 square miles. The residential quarters in the urban area of the Sagaing town are: 1.Pabetan, 2.Seingon, 3.Tagaung, 4.Minlan, 5.Moeza, 6.Ayemyawady, 7.Potan, 8.Nandawin, 9.Daweizay, * Associate Professor, Dr, Department of Oriental Studies, Yadanabon University 10.Myothit, 11.Ywahtaung, 12.Htonbo, 13.Thawtapan, 14.Parami, 15.Nilar, 16.Pattamya, 17.Shweminwun, 18.Zeyar, 19.Miyahtar, 20.Pyukan, 21.Kyauksit, 22.Magyisin, 23.Magyigon, 24.Tintate, and 25.Sitee. -

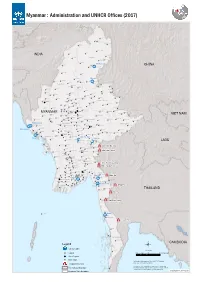

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017)

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017) Nawngmun Puta-O Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Sumprabum Lahe Tanai INDIA Tsawlaw Hkamti Kachin Chipwi Injangyang Hpakan Myitkyina Lay Shi Myitkyina CHINA Mogaung Waingmaw Homalin Mohnyin Banmauk Bhamo Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Momauk Pinlebu Katha Sagaing Mansi Muse Wuntho Konkyan Kawlin Tigyaing Namhkan Tonzang Mawlaik Laukkaing Mabein Kutkai Hopang Tedim Kyunhla Hseni Manton Kunlong Kale Kalewa Kanbalu Mongmit Namtu Taze Mogoke Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Falam Mingin Thabeikkyin Ye-U Khin-U Shan (North) ThantlangHakha Tabayin Hsipaw Namphan ShweboSingu Kyaukme Tangyan Kani Budalin Mongyai Wetlet Nawnghkio Ayadaw Gangaw Madaya Pangsang Chin Yinmabin Monywa Pyinoolwin Salingyi Matman Pale MyinmuNgazunSagaing Kyethi Monghsu Chaung-U Mongyang MYANMAR Myaung Tada-U Mongkhet Tilin Yesagyo Matupi Myaing Sintgaing Kyaukse Mongkaung VIET NAM Mongla Pauk MyingyanNatogyi Myittha Mindat Pakokku Mongping Paletwa Taungtha Shan (South) Laihka Kunhing Kengtung Kanpetlet Nyaung-U Saw Ywangan Lawksawk Mongyawng MahlaingWundwin Buthidaung Mandalay Seikphyu Pindaya Loilen Shan (East) Buthidaung Kyauktaw Chauk Kyaukpadaung MeiktilaThazi Taunggyi Hopong Nansang Monghpyak Maungdaw Kalaw Nyaungshwe Mrauk-U Salin Pyawbwe Maungdaw Mongnai Monghsat Sidoktaya Yamethin Tachileik Minbya Pwintbyu Magway Langkho Mongpan Mongton Natmauk Mawkmai Sittwe Magway Myothit Tatkon Pinlaung Hsihseng Ngape Minbu Taungdwingyi Rakhine Minhla Nay Pyi Taw Sittwe Ann Loikaw Sinbaungwe Pyinma!^na Nay Pyi Taw City Loikaw LAOS Lewe -

Study on Lotus Fiber Production in Sunn Ye Inn, Sintgaing Township

344 Banmaw University Research Journal 2020, Vol. 11, No.1 Study on Lotus Fiber Production in Sunn Ye Inn, Sintgaing Township San Win Abstract The lotus, Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. is grown naturally in Sunn Ye Inn in Sintgaing Township, Mandalay Region. The lotus stem especially leaf petiole is being extentsively used in the extraction of lotus fibers. It can be weaved to make the famous of lotus robe (Kyathingan) and other cloth materials. The raw material maily lotus fibers are obtained from Inn Khone Village in Sunn Ye Inn. The Sunn Ye Inn is the sources of lotus fiber production and foods for people. The N.nucifera Gaertn. is influenced on ecological impact of Sunn Ye Inn and eco-social impact of local people. Key words: Lotus, Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn, ecological impact, eco-social impact. Introduction Lotus plant has symbol of religion and spiritual power in history of Myanmar. Buddhists considered lotus flower represents the success, peaceful, fresh, graceful and pure mind. Because of its pristine value, Padonma Kya is also known as the sacred lotus. Ancient Myanmar Kings used lotus flower, bud, stems and petals in wall painting and statue (SK Myanmar Cultural Heritage 2016). All parts of lotus plant are useful, stem for producing lotus fiber, flower for offering to Buddha, leaves for packing food, meat etc. Lotus leaves are also used as plate to decorate food. Lotus root and seed are also edible (Hlaing 2016). Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. is an aquatic perennial belonging to the family of Nelumbonaceae, which has several common names (e.g. Indian lotus, Chinese water lily, and sacred lotus), lotus is a large and rhizomatous aquatic herb with slender, elongated, branched, creeping stem consisting of nodal roots; leaves are large, peltate; petioles are long, rough with small distinct prickles; flowers are white to rosy, sweet-scented, solitary, hermaphrodite, 10-25 cm diameter; ripe carpel are 12mm long, ovoid and glabrous; fruits are ovoid having nut like achene; seeds are black, hard and ovoid (Sridhar and Rajeev 2007).The lotus, N. -

Regional Polymorphism Assessment of Myanmar 'Sein Ta Lone' Mango

Horticulture Biotechnology Research 2019, 5: 017-022 doi: 10.25081/hbr.2019.v5.5447 https://updatepublishing.com/journal/index.php/hbr/ Research Article Regional polymorphism assessment of Myanmar ‘Sein Ta Lone’ mango (Mangifera indica Linn) from ISSN: 2455-460X Sintgaing Township based on microsatellite markers Seinn Sandar May Phyo, Nwe Nwe Soe Hlaing, May Sandar Kyaing*, Moe Moe Myint, April Nwet Yee Soe, Honey Thet Paing Htway, Khin Pyone Yi Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Biotechnology Research Department, Kyaukse, Mandalay Region, Myanmar ABSTRACT This study was conducted to explore the genetic diversity and relationship of Sein Ta Lone mango cultivars among 20 commercial orchards in Sintgaing Township, Mandalay region. Nine microsatellite (SSR) markers were used to detect genetic polymorphism in a range from (3 to 6) alleles with (4.33) alleles per marker in average. Six out of nine microsatellite markers gave the PIC values of greater than (0.5). Among them, SSR36 held the highest PIC values of Received: April 08, 2019 (0.691) while MiSHRS39 and MN85 possessed the least PIC values of (0.368) and (0.387) respectively. The genetic Accepted: May 03, 2019 diversity was expressed as unbiased expected heterozygosity (UHe) value with an average of (0.561). The genetic Published: May 05, 2019 relationship was revealed by (UPGMA) dendrogram in a range of (0.69 to 1.00). Based on UPGMA cluster analysis, three main clusters were classified among three different locations. This study was intended to help cultivar characterization and conservation for proper germplasm management with the estimation of genetic variation and relationship in the *Corresponding Author: existing population of Sein Ta Lone mangoes in Sintgaing Township by microsatellite markers. -

Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine

Urban Development Plan Development Urban The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Construction for Regional Cities The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Urban Development Plan for Regional Cities - Mawlamyine and Pathein Mandalay, - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - - - REPORT FINAL Data Collection Survey on Urban Development Planning for Regional Cities FINAL REPORT <SUMMARY> August 2016 SUMMARY JICA Study Team: Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. Nine Steps Corporation International Development Center of Japan Inc. 2016 August JICA 1R JR 16-048 Location業務対象地域 Map Pannandin 凡例Legend / Legend � Nawngmun 州都The Capital / Regional City Capitalof Region/State Puta-O Pansaung Machanbaw � その他都市Other City and / O therTown Town Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Don Hee 道路Road / Road � Shin Bway Yang � 海岸線Coast Line / Coast Line Sumprabum Tanai Lahe タウンシップ境Township Bou nd/ Townshipary Boundary Tsawlaw Hkamti ディストリクト境District Boundary / District Boundary INDIA Htan Par Kway � Kachinhin Chipwi Injangyang 管区境Region/S / Statetate/Regi Boundaryon Boundary Hpakan Pang War Kamaing � 国境International / International Boundary Boundary Lay Shi � Myitkyina Sadung Kan Paik Ti � � Mogaung WaingmawミッチMyitkyina� ーナ Mo Paing Lut � Hopin � Homalin Mohnyin Sinbo � Shwe Pyi Aye � Dawthponeyan � CHINA Myothit � Myo Hla Banmauk � BANGLADESH Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Katha Momauk Lwegel � Pinlebu Monekoe Maw Hteik Mansi � � Muse�Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Cikha Wuntho �Manhlyoe (Manhero) � Namhkan Konkyan Kawlin Khampat Tigyaing � Laukkaing Mawlaik Tonzang Tarmoenye Takaung � Mabein -

Myanmar Situation Update (12 - 18 July 2021)

Myanmar Situation Update (12 - 18 July 2021) Summary Myanmar detained State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, President U Win Myint and former Naypyitaw Council Chairman Dr. Myo Aung appeared at a special court in Naypyitaw’s Zabuthiri township for their trial for incitement under Section 505(b) of the Penal Code. The junta filed fresh charges against Suu Kyi, bringing the number of cases she faces to ten with a potential prison sentence of 75 years. The next court hearings of their trial have been moved to July 26 and 27, following the junta’s designation of a week-long public holiday and lockdown order. Senior National League for Democracy (NLD) patron Win Htein was indicted on a sedition charge by a court inside a Naypyitaw detention center with a possible prison sentence of up to 20 years. The state- run MRTV also reported the Anti-Corruption Commission (AAC) made a complaint against the former Chief Minister of Shan State, three former state ministers, and three people under the anti-corruption law at Taunggyi Township police station while the junta has already filed corruption cases against many former State Chief Ministers under the NLD government. During the press conference on 12 July 2021 in Naypyitaw, the junta-appointed Union Election Commission (UEC) announced that 11,305,390 voter list errors were found from the investigation conducted by the UEC. The UEC also said the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is investigating foreign funding of political parties and the investigation reports will be published soon with legal actions to be taken against the parties who violate the law.