For Peer Review Only - Page 1 of 27 BMJ Open

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemical Disinfectants for Biohazardous Materials (3/21)

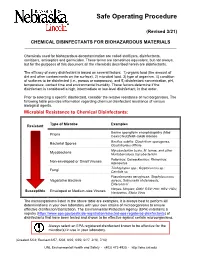

Safe Operating Procedure (Revised 3/21) CHEMICAL DISINFECTANTS FOR BIOHAZARDOUS MATERIALS ____________________________________________________________________________ Chemicals used for biohazardous decontamination are called sterilizers, disinfectants, sanitizers, antiseptics and germicides. These terms are sometimes equivalent, but not always, but for the purposes of this document all the chemicals described herein are disinfectants. The efficacy of every disinfectant is based on several factors: 1) organic load (the amount of dirt and other contaminants on the surface), 2) microbial load, 3) type of organism, 4) condition of surfaces to be disinfected (i.e., porous or nonporous), and 5) disinfectant concentration, pH, temperature, contact time and environmental humidity. These factors determine if the disinfectant is considered a high, intermediate or low-level disinfectant, in that order. Prior to selecting a specific disinfectant, consider the relative resistance of microorganisms. The following table provides information regarding chemical disinfectant resistance of various biological agents. Microbial Resistance to Chemical Disinfectants: Type of Microbe Examples Resistant Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (Mad Prions Cow) Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Bacillus subtilis; Clostridium sporogenes, Bacterial Spores Clostridioides difficile Mycobacterium bovis, M. terrae, and other Mycobacteria Nontuberculous mycobacterium Poliovirus; Coxsackievirus; Rhinovirus; Non-enveloped or Small Viruses Adenovirus Trichophyton spp.; Cryptococcus sp.; -

EH&S COVID-19 Chemical Disinfectant Safety Information

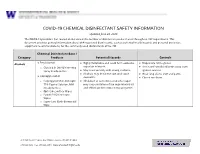

COVID-19 CHEMICAL DISINFECTANT SAFETY INFORMATION Updated June 24, 2020 The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an increase in the number of disinfection products used throughout UW departments. This document provides general information about EPA-registered disinfectants, such as potential health hazards and personal protective equipment recommendations, for the commonly used disinfectants at the UW. Chemical Disinfectant Base / Category Products Potential Hazards Controls ● Ethyl alcohol Highly flammable and could form explosive Disposable nitrile gloves Alcohols ● ● vapor/air mixtures. ● Use in well-ventilated areas away from o Clorox 4 in One Disinfecting Spray Ready-to-Use ● May react violently with strong oxidants. ignition sources ● Alcohols may de-fat the skin and cause ● Wear long sleeve shirt and pants ● Isopropyl alcohol dermatitis. ● Closed toe shoes o Isopropyl Alcohol Antiseptic ● Inhalation of concentrated alcohol vapor 75% Topical Solution, MM may cause irritation of the respiratory tract (Ready to Use) and effects on the central nervous system. o Opti-Cide Surface Wipes o Powell PII Disinfectant Wipes o Super Sani Cloth Germicidal Wipe 201 Hall Health Center, Box 354400, Seattle, WA 98195-4400 206.543.7262 ᅵ fax 206.543.3351ᅵ www.ehs.washington.edu ● Formaldehyde Formaldehyde in gas form is extremely Disposable nitrile gloves for Aldehydes ● ● flammable. It forms explosive mixtures with concentrations 10% or less ● Paraformaldehyde air. ● Medium or heavyweight nitrile, neoprene, ● Glutaraldehyde ● It should only be used in well-ventilated natural rubber, or PVC gloves for ● Ortho-phthalaldehyde (OPA) areas. concentrated solutions ● The chemicals are irritating, toxic to humans ● Protective clothing to minimize skin upon contact or inhalation of high contact concentrations. -

Hydroxy- -Methylbutyrate (Hmb)

(19) *EP003373740B1* (11) EP 3 373 740 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A23K 10/10 (2016.01) A23L 33/10 (2016.01) 24.02.2021 Bulletin 2021/08 (86) International application number: (21) Application number: 16864978.8 PCT/US2016/061278 (22) Date of filing: 10.11.2016 (87) International publication number: WO 2017/083487 (18.05.2017 Gazette 2017/20) (54) COMPOSITIONS AND METHODS OF USE OF -HYDROXY- -METHYLBUTYRATE (HMB) AS AN ANIMAL FEED ADDITIVE ZUSAMMENSETZUNGEN UND VERFAHREN ZUR VERWENDUNG VON BETA-HYDROXY-BETA-METHYLBUTYRAT (HMB) ALS FUTTERZUSATZ COMPOSITIONS ET PROCÉDÉS D’UTILISATION DE -HYDROXY- -MÉTHYLBUTYRATE (HMB) COMME ADDITIF D’ALIMENT POUR ANIMAUX (84) Designated Contracting States: • BAIER, Shawn AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB Polk City, Iowa 50226 (US) GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR (74) Representative: Evans, Jacqueline Gail Victoria Marches Intellectual Property Limited (30) Priority: 10.11.2015 US 201562253428 P Wyastone Business Park Wyastone Leys (43) Date of publication of application: Ganarew 19.09.2018 Bulletin 2018/38 Monmouth NP25 3SR (GB) (73) Proprietor: Metabolic Technologies, Inc. (56) References cited: Ames, IA 50010 (US) WO-A1-2004/037010 US-A- 5 028 440 US-A- 5 087 472 US-A- 5 087 472 (72) Inventors: US-A- 6 103 764 US-A1- 2014 249 223 • FULLER, John US-A1- 2015 025 145 Zearing, Iowa 50278 (US) • RATHMACHER, John Story City, Iowa 50248 (US) Note: Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the Implementing Regulations. -

Amoxicillin in Water: Insights Into Relative Reactivity, Byproduct Formation, and Toxicological Interactions During Chlorination

applied sciences Article Amoxicillin in Water: Insights into Relative Reactivity, Byproduct Formation, and Toxicological Interactions during Chlorination Antonietta Siciliano 1 , Marco Guida 1 , Giovanni Libralato 1 , Lorenzo Saviano 1, Giovanni Luongo 2 , Lucio Previtera 3, Giovanni Di Fabio 2 and Armando Zarrelli 2,* 1 Department of Biology, University of Naples Federico II, 80126 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (G.L.); [email protected] (L.S.) 2 Department of Chemical Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, 80126 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (G.L.); [email protected] (G.D.F.) 3 Associazione Italiana per la Promozione delle Ricerche su Ambiente e Salute umana, 82030 Dugenta, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-08-167-4472 Abstract: In recent years, many studies have highlighted the consistent finding of amoxicillin in waters destined for wastewater treatment plants, in addition to superficial waters of rivers and lakes in both Europe and North America. In this paper, the amoxicillin degradation pathway was investigated by simulating the chlorination process normally used in a wastewater treatment plant to reduce similar emerging pollutants at three different pH values. The structures of 16 isolated Citation: Siciliano, A.; Guida, M.; degradation byproducts (DPs), one of which was isolated for the first time, were separated on a Libralato, G.; Saviano, L.; Luongo, G.; C-18 column via a gradient HPLC method. Combining mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic Previtera, L.; Di Fabio, G.; Zarrelli, A. resonance, we then compared commercial standards and justified a proposed formation mechanism Amoxicillin in Water: Insights into beginning from the parent drug. -

HIV-2 BLOT 1.2 Instructions for Use

HIV-2 BLOT 1.2 Instructions For Use FOR RESEARCH USE ONLY NOT FOR USE IN DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES REVISION DATE: 2017/05 Note Changes Highlighted MAC0012-ENG-1 (18 Tests): 11022-018 (36 Tests): 11022-036 NAME AND INTENDED USE The MP DIAGNOSTICS HIV-2 BLOT 1.2 is a qualitative enzyme immunoassay for in-vitro detection of specific antibodies to HIV-2 in human serum or plasma. This test kit is supplied for research purposes only. It is not intended for use in the diagnosis or prognosis of disease. In particular, this test cannot be used to evaluate blood specimens for the purposes of donor screening or as a confirmatory diagnostic. INTRODUCTION The MP Diagnostics HIV-2 BLOT 1.2 kit is intended as a supplemental antibody assay for Research Use Only. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 2 (HIV-2) infection was first described in 1985 in asymptomatic prostitutes from Senegal. The virus was subsequently isolated in 1986 from patients with AIDS-like symptoms in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde. HIV-2 is related to, but distinct from HIV-1, the prototype AIDS virus. As such HIV-2 has many molecular, biological and serological similarities with HIV-1. Reports have shown that the infection is not limited to Africa and that HIV-2 seropositive individuals have been identified in Europe and the United States. DESCRIPTIONS OF SYMBOLS USED The following are graphical symbols used in or found on MP Diagnostics products and packaging. These symbols are the most common ones appearing on medical devices and their packaging. Some of the common symbols are explained in more detail in European Standard BS EN 980:2008 and International Standard ISO 15223-1:2007. -

Sodium Hypochlorite

SODIUM HYPOCHLORITE What is SODIUM HYPOCHLORITE? Sodium hypochlorite is a liquid with an odor of chlorine. Usually it is clear but some solutions are greenish to yellow in color. Other names for sodium hypochlorite include Clorox , bleach, liquid bleach, sodium oxychloride, Javex, antiformin, showchlon, Chlorox, B-K, Carrel-Dakin Solution, Chloros, Dakin’s Solution, hychlorite, Javelle Water, Mera Industries 2MOm≥B, Milton, modified Dakin’s Solution, Piochlor, and 13% active chlorine. Where can sodium hypochlorite be found and how is it used? Sodium hypochlorite is mainly used as a bleaching agent or disinfectant. A disinfectant kills bacteria that can carry diseases. It is found in consumer and commercial bleaches, cleaning solutions, and disinfectants for drinking water, wastewater and swimming pools. How can people be exposed to sodium hypochlorite? You could be exposed to sodium hypochlorite through: Breathing fumes while using products containing sodium hypochlorite. Drinking water from public drinking water supplies where these chemicals were added to kill bacteria. You could also be exposed by drinking sodium hypochlorite by accident. Touching sodium hypochlorite if gloves are not worn when using products containing it. Eye Contact by splashing sodium hypochlorite during use. People who work where sodium hypochlorite is used to bleach paper and textiles may have slightly higher levels of exposure in all of the above areas. How does sodium hypochlorite work and how can it affect my health? Sodium hypochlorite is a corrosive substance, meaning that it will eat away at materials it contacts. Accidental sodium hypochlorite poisoning can be deadly. Severe injuries can occur to the mouth, throat, esophagus and stomach. -

Kinetic Studies on Oxidative Dissolution of Elemental Mercury in Aqueous Sodium Hypochlorite

International Journal of Environmental Science and Development, Vol. 7, No. 7, July 2016 Kinetic Studies on Oxidative Dissolution of Elemental Mercury in Aqueous Sodium Hypochlorite S. Bandyopadhyay, S. Chakraborty, D. B. Zaini, and S. Bhattacharjee mercury and second order reaction kinetics was observed Abstract—Aqueous sodium hypochlorite is often used to between elemental mercury and free chlorine. detoxify solid wastes containing elemental mercury and its Solid wastes are often treated with aqueous sodium compounds by oxidative dissolution of mercury in the form of a hypochlorite to remove mercury and its compounds. Brine soluble mercurochloro complex. Experiments were conducted to estimate global kinetics and interfacial mass transfer mud of a chlor-alkali industry containing elemental mercury parameters of the reaction between elemental mercury and and its salts is a solid waste and is usually dumped off-site in a aqueous sodium hypochlorite. The reaction did not conform to lined pond. Sometimes this brine mud is treated with aqueous either pure mass transfer or pure instantaneous reaction sodium hypochlorite to remove toxic mercury from the sludge. regimes. The order and activation energy of the reaction were This is a solid-liquid reaction and involves mass transfer of -1 estimated to be 1.168 and 13.48 kJ mol respectively. mercury from the solid matrix into a liquid phase. Sizeneva et Experimental data on reaction enhancement factors may be used al. [10] studied oxidative dissolution of Hg0 in NaOCl at pH for design of an industrial solid waste detoxification reactor. 0 0 5.9, 6.5, 6.9 and 8.5 at 25 C and 50 C. -

COVID-19 Environmental Cleaning and Disinfectants for Clinic

Coronavirus COVID-19 BC Centre for Disease Control | BC Ministry of Health Environmental Cleaning and Disinfectants for Health-Care and Clinic Settings Cleaning: the physical removal of visible soiling (e.g., dust, soil, blood, mucus). Cleaning removes, rather than kills, viruses and bacteria. It is done with water, detergents, and steady friction from cleaning cloth. Disinfection: the killing of viruses and bacteria. A disinfectant is only applied to objects; never on the human body. All visibly soiled surfaces should be cleaned before disinfection. Environmental cleaning for the COVID-19 virus is the same as for other common viruses. Cleaning products and disinfectants that are regularly used in hospitals and health-care settings are strong enough to deactivate coronaviruses and prevent their spread. Cleaning of visibly soiled surfaces followed by disinfection is recommended for the prevention of COVID-19 and other viral respiratory illnesses. Suggested cleaning and disinfecting frequencies for health-care and clinic settings: Type of surface Frequency 1. Shared equipment IN BETWEEN PATIENTS otoscopes, baby scales, tables and exam beds 2. Frequently-touched surfaces Examples: medical equipment, door knobs, light AT LEAST TWICE A DAY switches, telephones, keyboards, mice, pens, charts, cell phones, toys, bathrooms 3. General cleaning of procedure / exam rooms AT LEAST ONCE A DAY For electronic equipment please comply with manufacturer’s instructions in order to meet warranty requirements 06.02.21 Coronavirus COVID-19 BC Centre for Disease Control | BC Ministry of Health Environmental Cleaning and Disinfectants for Health-Care and Clinic Settings The list of common disinfectants below is provided as a guide to choosing products. -

Disinfection of Tonometers a Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology

Ophthalmic Technology Assessment Disinfection of Tonometers A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology Anna K. Junk, MD,1 Philip P. Chen, MD,2 Shan C. Lin, MD,3 Kouros Nouri-Mahdavi, MD,4 Sunita Radhakrishnan, MD,5 Kuldev Singh, MD, MPH,6 Teresa C. Chen, MD7 Objective: To examine the efficacy of various disinfection methods for reusable tonometer prisms in eye care and to highlight how disinfectants can damage tonometer tips and cause subsequent patient harm. Methods: Literature searches were conducted last in October 2016 in the PubMed and the Cochrane Library databases for original research investigations. Reviews, non-English language articles, nonophthalmology articles, surveys, and case reports were excluded. Results: The searches initially yielded 64 unique citations. After exclusion criteria were applied, 10 labo- ratory studies remained for this review. Nine of the 10 studies used tonometer prisms and 1 used steel discs. The infectious agents covered in this assessment include adenovirus 8 and 19, herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1 and 2, human immunodeficiency virus 1, hepatitis C virus, enterovirus 70, and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. All 4 studies of adenovirus 8 concluded that after sodium hypochlorite (dilute bleach) disinfection, the virus was undetectable, but only 2 of the 4 studies found that 70% isopropyl alcohol (e.g., alcohol wipes or soaks) eradicated all viable virus. All 3 HSV studies concluded that both sodium hypochlorite and 70% isopropyl alcohol eliminated HSV. Ethanol, 70% isopropyl alcohol, dilute bleach, and mechanical cleaning all lack the ability to remove cellular debris completely, which is necessary to prevent prion transmission. Therefore, single-use tonometer tips or disposable tonometer covers should be considered when treating patients with suspected prion disease. -

SODIUM HYPOCHLORITE, AKA “LIQUID CHLORINE” in Other Words, Bleach by the PHTA Recreational Water Quality Committee

TECH NOTES SODIUM HYPOCHLORITE, AKA “LIQUID CHLORINE” In other words, bleach By the PHTA Recreational Water Quality Committee IN THE SWIMMING pool industry, one gallon of 12.5% sodium hypochlorite a corrosive. As such, a maximum of of the most popularly chosen forms for provides approximately 12.5 ppm of 500 gallons can be stored in a non-fire, sanitizing and superchlorinating water free chlorine per 10,000 gallons of sprinkler-protected room and 1,000 is sodium hypochlorite. Commonly pool water. It takes 10.6 fl. oz of 12.5% gallons in a fire, sprinkler-protected known as “liquid chlorine” or bleach, sodium hypochlorite to get roughly room as maximum exempt quantities. sodium hypochlorite is widely used 1 ppm of free chlorine in 10,000 gallons Quantities beyond this create an “H” in both commercial and residential of pool water. The pH of pool grade Hazardous Occupancy and require swimming pools. Sodium hypochlorite sodium hypochlorite is 13. special fire protection. effectively destroys bacteria and Sodium hypochlorite is Sodium hypochlorite reacts prevents algae in swimming pools. classified as an inorganic sanitizer; in water to create hypochlorous This edition of Tech Notes provides it does not contain cyanuric acid. information on the characteristics, Sodium hypochlorite is a primary effects and proper application of sanitizer because of its ability to SODIUM HYPOCHLORITE: THE sodium hypochlorite. kill microorganisms, oxidize non- living contaminants like ammonia BASIC FACTS WHAT IT IS and swimmers’ waste and provide • Clear yellow liquid with a Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), a protective residual in the water. chlorine odor commonly referred to as “liquid Sodium hypochlorite is non-flammable, • A solution containing chlorine” or liquid bleach, is an non-combustible and non-explosive, water, hypochlorite, sodium aqueous solution created by and containers under 1.3 gallons hydroxide and a trace amount mixing chlorine gas in water with aretransported as “Limited Quantities” of sodium chloride concentrations of sodium hydroxide. -

FACT SHEET Chemical Disinfectants

FACT SHEET Chemical Disinfectants In the laboratory setting, chemical disinfection is the most common method employed to decontaminate surfaces and disinfect waste liquids. In most laboratories, dilutions of household bleach is the preferred method but there are many alternatives that may be considered and could be more appropriate for some agents or situations. There are numerous commercially available products that have been approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). EPA Registered Sterilizers, Tuberculocides, and Antimicrobial Products Against Certain Human Public Health Bacteria and Viruses can be found at https://www.epa.gov/pesticide- registration/selected-epa-registered-disinfectants Most EPA-registered disinfectants have a 10-minute label claim. However, OEHS Biosafety recommends a 15-20 minute contact time for disinfection/decontamination. General Considerations Prior to using a chemical disinfectant always consult the manufacturer’s instructions to determine the efficacy of the disinfectant against the biohazards in your lab and be sure to allow for sufficient contact time. In addition, consult the Safety Data Sheet for information regarding hazards, the appropriate protective equipment for handling the disinfectant and disposal of disinfected treated materials. Federal law requires all applicable label instructions on EPA-registered products to be followed (e.g., use-dilution, shelf life, storage, material compatibility, safe use, and disposal). Do not attempt to use a chemical disinfectant for a purpose it was not designed for. • When choosing a disinfectant consider the following: • The microorganisms present • The item to be disinfected or surface(s) • Corrosivity or hazards associated with the chemicals in the disinfectant • Ease of use 1. Organism Sensitivity and Resistant Organisms The innate characteristics of microorganisms often determine its sensitivity to chemical disinfection (Table 1). -

COVID-19: Guidelines on Disinfection of Common Public Places Including Offices

COVID-19: Guidelines on disinfection of common public places including offices Scope: This document aims to provide interim guidance about the environmental cleaning /decontamination of common public places including offices in areas reporting COVID-19. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID -19) is an acute respiratory disease caused by a novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), transmitted in most instances through respiratory droplets, direct contact with cases and also through contaminated surfaces/objects. Though the virus survives on environmental surfaces for varied period of time, it gets easily inactivated by chemical disinfectants. In view of the above, the following guidelines are to be followed, especially in areas reporting COVID-19. For ease of implementation the guideline divided these areas into (i) indoor areas, (ii) outdoor areas and (iii) public toilets. 1. Indoor areas including office spaces Office spaces, including conference rooms should be cleaned every evening after office hours or early in the morning before the rooms are occupied. If contact surface is visibly dirty, it should be cleaned with soap and water prior to disinfection. Prior to cleaning, the worker should wear disposable rubber boots, gloves (heavy duty), and a triple layer mask. Start cleaning from cleaner areas and proceed towards dirtier areas. All indoor areas such as entrance lobbies, corridors and staircases, escalators, elevators, security guard booths, office rooms, meeting rooms, cafeteria should be mopped with a disinfectant with 1% sodium hypochlorite