Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Arizona 500 2021 Final List of Songs

ARIZONA 500 2021 FINAL LIST OF SONGS # SONG ARTIST Run Time 1 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 4:20 2 YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC 3:28 3 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY QUEEN 5:49 4 KASHMIR LED ZEPPELIN 8:23 5 I LOVE ROCK N' ROLL JOAN JETT AND THE BLACKHEARTS 2:52 6 HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN? CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL 2:34 7 THE HAPPIEST DAYS OF OUR LIVES/ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO 5:35 8 WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE GUNS N' ROSES 4:23 9 ERUPTION/YOU REALLY GOT ME VAN HALEN 4:15 10 DREAMS FLEETWOOD MAC 4:10 11 CRAZY TRAIN OZZY OSBOURNE 4:42 12 MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON 4:40 13 CARRY ON WAYWARD SON KANSAS 5:17 14 TAKE IT EASY EAGLES 3:25 15 PARANOID BLACK SABBATH 2:44 16 DON'T STOP BELIEVIN' JOURNEY 4:08 17 SWEET HOME ALABAMA LYNYRD SKYNYRD 4:38 18 STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN LED ZEPPELIN 7:58 19 ROCK YOU LIKE A HURRICANE SCORPIONS 4:09 20 WE WILL ROCK YOU/WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS QUEEN 4:58 21 IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS 5:21 22 LIVE AND LET DIE PAUL MCCARTNEY AND WINGS 2:58 23 HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC 3:26 24 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 4:21 25 EDGE OF SEVENTEEN STEVIE NICKS 5:16 26 BLACK DOG LED ZEPPELIN 4:49 27 THE JOKER STEVE MILLER BAND 4:22 28 WHITE WEDDING BILLY IDOL 4:03 29 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL ROLLING STONES 6:21 30 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 3:34 31 HEARTBREAKER PAT BENATAR 3:25 32 COME TOGETHER BEATLES 4:06 33 BAD COMPANY BAD COMPANY 4:32 34 SWEET CHILD O' MINE GUNS N' ROSES 5:50 35 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHEAP TRICK 3:33 36 BARRACUDA HEART 4:20 37 COMFORTABLY NUMB PINK FLOYD 6:14 38 IMMIGRANT SONG LED ZEPPELIN 2:20 39 THE -

Het Verhaal Van De 340 Songs Inhoud

Philippe Margotin en Jean-Michel Guesdon Rollingthe Stones compleet HET VERHAAL VAN DE 340 SONGS INHOUD 6 _ Voorwoord 8 _ De geboorte van een band 13 _ Ian Stewart, de zesde Stone 14 _ Come On / I Want To Be Loved 18 _ Andrew Loog Oldham, uitvinder van The Rolling Stones 20 _ I Wanna Be Your Man / Stoned EP DATUM UITGEBRACHT ALBUM Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down The Road Apiece ALBUM DATUM UITGEBRACHT 10 januari 1964 EP Everybody Needs Somebody To Love Under The Boardwalk DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : (er zijn ook andere data, zoals DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : 17 april 1964 16, 17 of 18 januari genoemd Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down Home Girl I Can’t Be Satisfi ed 15 januari 1965 Label Decca als datum van uitbrengen) 14 augustus 1964 You Can’t Catch Me Pain In My Heart Label Decca REF : LK 4605 Label Decca Label Decca Time Is On My Side Off The Hook REF : LK 4661 12 weken op nummer 1 REF : DFE 8560 REF : DFE 8590 10 weken op nummer 1 What A Shame Susie Q Grown Up Wrong TH TH TH ROING (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 FIVE I Just Want To Make Love To You Honest I Do ROING ROING I Need You Baby (Mona) Now I’ve Got A Witness (Like Uncle Phil And Uncle Gene) Little By Little H ROLLIN TONS NOW VRNIGD TATEN EBRUARI 965) I’m A King Bee Everybody Needs Somebody To Love / Down Home Girl / You Can’t Catch Me / Heart Of Stone / What A Shame / I Need You Baby (Mona) / Down The Road Carol Apiece / Off The Hook / Pain In My Heart / Oh Baby (We Got A Good Thing SONS Tell Me (You’re Coming Back) If You Need Me Goin’) / Little Red Rooster / Surprise, Surprise. -

Something Happened to Me Yesterday © Felix Aeppli 12-2019 / 09-2020

SPARKS WILL FLY 2018 Something Happened To Me Yesterday © Felix Aeppli 12-2019 / 09-2020 “UK, IRE and EU No Filter Tour” APRIL 30 – MAY 4 Rehearsals, Omnibus Theatre, Clapham, London MAY 7-11 Rehearsals, Unidentified venue, London 14 Rehearsals, Croke Park, Dublin (Entry 1.229) 15 Rehearsals, Croke Park, Dublin (Entry 1.230) 17 Croke Park, Dublin (Entry 1.232 – complete show listed) 22 London Stadium, London (Entry 1.234 – complete show listed) 25 London Stadium, London (Entry 1.235 – complete show listed) (joined by Florence Welch) 29 St Mary’s Stadium, Southampton (Entry 1.236 – complete show listed) JUNE 2 Ricoh Arena, Coventry (Entry 1.237 – complete show listed) 5 Old Trafford Football Stadium, Manchester (Entry 1.238 – complete show listed) 9 BT Murrayfield Stadium, Edinburgh (Entry 1.239 – complete show listed) 15 Principality Stadium, Cardiff (Entry 1.240 – complete show listed) 19 Twickenham Stadium, London (Entry 1.242 – complete show listed) (joined by James Bay) 22 Olympiastadion, Berlin (Entry 1.243 – complete show listed) 26 Orange Velodrome, Marseille (Entry 1.244 – complete show listed) 30 Mercedes-Benz Arena, Stuttgart (Entry 1.245 – complete show listed) JULY 4 Letnany Airport, Prague (Entry 1.247 – complete show listed) 8 PGE Narodowy, Warsaw (Entry 1.248 – complete show listed) Backing: Chuck Leavell: keyboards, back-up vocals, percussion; Darryl Jones: bass, occasional back-up vocals; Karl Denson: saxophone; Tim Ries: horns, occa- sional keyboards; Matt Clifford: keyboards, occasional percussion and French horn; Sasha -

Sympathy for the Devil – the Creative Transformation of the Evil

JOURNAL OF GENIUS AND EMINENCE, 5 (1) 2020 Article 1 | pages 4-14 Issue Copyright © 2020 Tinkr Article Copyright © 2020 Rainer Matthias Holm-Hadulla ISSN: 2334-1149 online DOI: 10.18536/jge.2020.01.01 Sympathy for the Devil – The Creative Transformation of the Evil Rainer Matthias Holm-Hadulla Heidelberg University Abstract Mythologies, religions, philosophies, and ideologies show that all cultures are concerned with human destructivity. The same is readily apparent in many modern creative works of eminence. In their famous song, “Sympathy for the Devil,” Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones refer to Goethe’s Faust, where the Devil is characterized strangely as “a portion of that power/ which always works for the Evil and effects the Good ... a part of Darkness which gave birth to Light”. These verses remind one of ancient myth but also of modern ideas of the interplay of creation and destruction. The poetry of Goethe, the scientific psychoanalysis of Freud, and the aesthetic enactments of Madonna Ciccone and Mick Jagger show that the creative transformation of destructiveness provides a chance to cope with evil. Through his poetic and autobiographic self-reflection Goethe described how men are composed of constructive and destructive forces, light and dark, good and evil. This dialectic of drives and activities is also fundamental for the Freudian scientific model of the mind and its interrelation with the body and the social environment. Humans can only survive when they transform their destructive inclinations into constructive activities. The creative transformation of destructiveness is also a central issue in today’s pop culture. Paradigmatically the song ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ describes the atrocities humans are able to commit. -

Sympathy for the Devil: Volatile Masculinities in Recent German and American Literatures

Sympathy for the Devil: Volatile Masculinities in Recent German and American Literatures by Mary L. Knight Department of German Duke University Date:_____March 1, 2011______ Approved: ___________________________ William Collins Donahue, Supervisor ___________________________ Matthew Cohen ___________________________ Jochen Vogt ___________________________ Jakob Norberg Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of German in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 ABSTRACT Sympathy for the Devil: Volatile Masculinities in Recent German and American Literatures by Mary L. Knight Department of German Duke University Date:_____March 1, 2011_______ Approved: ___________________________ William Collins Donahue, Supervisor ___________________________ Matthew Cohen ___________________________ Jochen Vogt ___________________________ Jakob Norberg An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of German in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Mary L. Knight 2011 Abstract This study investigates how an ambivalence surrounding men and masculinity has been expressed and exploited in Pop literature since the late 1980s, focusing on works by German-speaking authors Christian Kracht and Benjamin Lebert and American author Bret Easton Ellis. I compare works from the United States with German and Swiss novels in an attempt to reveal the scope – as well as the national particularities – of these troubled gender identities and what it means in the context of recent debates about a “crisis” in masculinity in Western societies. My comparative work will also highlight the ways in which these particular literatures and cultures intersect, invade, and influence each other. In this examination, I demonstrate the complexity and success of the critical projects subsumed in the works of three authors too often underestimated by intellectual communities. -

1. Rush - Tom Sawyer 2

1. Rush - Tom Sawyer 2. Black Sabbath - Iron Man 3. Def Leppard - Photograph 4. Guns N Roses - November Rain 5. Led Zeppelin - Stairway to Heaven 6. AC/DC - Highway To Hell 7. Aerosmith - Sweet Emotion 8. Metallica - Enter Sandman 9. Nirvana - All Apologies 10. Black Sabbath - War Pigs 11. Guns N Roses - Paradise City 12. Tom Petty - Refugee 13. Journey - Wheel In The Sky 14. Led Zeppelin - Kashmir 15. Jimi Hendrix - All Along The Watchtower 16. ZZ Top - La Grange 17. Pink Floyd - Another Brick In The Wall 18. Black Sabbath - Paranoid 19. Soundgarden - Black Hole Sun 20. Motley Crue - Home Sweet Home 21. Derek & The Dominoes - Layla 22. Rush - The Spirit Of Radio 23. Led Zeppelin - Rock And Roll 24. The Who - Baba O Riley 25. Foreigner - Hot Blooded 26. Lynyrd Skynyrd - Freebird 27. ZZ Top - Cheap Sunglasses 28. Pearl Jam - Alive 29. Dio - Rainbow In The Dark 30. Deep Purple - Smoke On The Water 31. Nirvana - In Bloom 32. Jimi Hendrix - Voodoo Child (Slight Return) 33. Billy Squier - In The Dark 34. Pink Floyd - Wish You Were Here 35. Rush - Working Man 36. Led Zeppelin - Whole Lotta Love 37. Black Sabbath - NIB 38. Foghat - Slow Ride 39. Def Leppard - Armageddon It 40. Boston - More Than A Feeling 41. AC/DC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 42. Ozzy Osbourne - Crazy Train 43. Aerosmith - Walk This Way 44. Led Zeppelin - Dazed & Confused 45. Def Leppard - Rock Of Ages 46. Ozzy Osbourne - No More Tears 47. Eric Clapton - Cocaine 48. Ted Nugent - Stranglehold 49. Aerosmith - Dream On 50. Van Halen - Eruption / You Really Got Me 51. -

Something Happened to Me Yesterday © Felix Aeppli 06-2019 / 06-2020

TUMBLING DICE / FOOL TO CRY 1974 Something Happened To Me Yesterday © Felix Aeppli 06-2019 / 06-2020 FEBRUARY 8-13 Musicland Studios, Munich (Entry 0.249A) FEBRUARY 20 – MARCH 3 Musicland Studios, Munich (Entry 0.249A) APRIL 10-15 Rolling Stones Mobile (RSM), Stargroves, Newbury, Hampshire (Entry 0.249B) JUNE 1 Promotional film recordings, probably LWT Studios, London (Entry 0.250B) DECEMBER 7-15 Musicland Studios, Munich (Entry 0.254) 1974 Links Ian McPherson’s Stonesvaganza http://www.timeisonourside.com/chron1974.html Nico Zentgraf’s Database http://www.nzentgraf.de/books/tcw/1974.htm Ian McPherson’s Discography http://www.timeisonourside.com/disco3.html Which Album May I Show You? http://www.beatzenith.com/the_rolling_stones/rs2.htm#74iorr Sessions & Bootlegs at a Glance https://dbboots.com/content.php?op=lstshow&cmd=showall&year=1974 Japanese Archives Studio Website https://www10.atwiki.jp/stones/m/pages/282.html?guid=on The Rolling Stones on DVD http://www.beatlesondvd.com/19701974/1974year-sto.htm NOTES: Whilst every care has been taken in selecting these links, the author, of course, cannot guarantee that the links will continue to be active in the future. Further, the author is not responsible for the copyright or legality of the linked websites. TUMBLING DICE / FOOL TO CRY 1974 Sing This All Together LIVE & MEDIA SHOWS STUDIO SESSIONS RELEASES 0.248A JANUARY, 1974 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL (SINGLE), DECCA DL 25610 (WEST GERMANY) A Sympathy For The Devil B Prodigal Son (Rev. Wilkins) Side A: Recorded at the One Plus One sessions, Olympic Sound Studios, London, June 4-10, 1968. -

Top 100 Rock Songs

Top 100 Rock Songs (Determined by a panel of 700 music industry voters. Broadcast by music television station VH-1 during week of January 17, 2000) 1. Satisfaction – Rolling Stones 2. Respect – Aretha Franklin 3. Stairway to Heaven – Led Zeppelin 4. Like a Rolling Stone – Bob Dylan 5. Born to Run – Bruce Springsteen 6. Hotel California – Eagles 7. Light My Fire – Doors 8. Good Vibrations – Beach Boys 9. Hey Jude – Beatles 10. Imagine – John Lennon 11. Louie Louie – Kingsmen 12. Yesterday – Beatles 13. My Generation – the Who 14. What’s Going On – Marvin Gaye 15. Johnny B. Goode – Chuck Berry 16. Layla – Derek and the Dominos 17. Won’t Get Fooled Again – the Who 18. Jailhouse Rock – Elvis Presley 19. American Pie – Don McLean 20. A Day in the Life – Beatles 21. I Got You (I Feel Good) – James Brown 22. Superstition – Stevie Wonder 23. I Want to Hold Your Hand – Beatles 24. Brown Suger – Rolling Stones 25. Purple Haze – Jimi Hendrix 26. Sympathy for the Devil – Rolling Stones 27. Bohemian Rhapsody – Queen 28. You Really Got Me – the Kinks 29. Oh Pretty Woman – Roy Orbison 30. Bridge Over Troubled Water – Simon & Garfunkel 31. Hound Dog – Elvis Presley 32. Let It Be – Beatles 33. (Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay – Otis Redding 34. All Along the Watchtower – Jimi Hendrix Experience 35. Walk This Way – Aerosmith 36. My Girl – Temptations 37. Rock Around the Clock – Bill Haley & His Comets 38. I Heard It Through the Grapevine – Marvin Gaye 39. Proud Mary - Creedence Clearwater Revival 40. Born to Be Wild – Steppenwolf 41. -

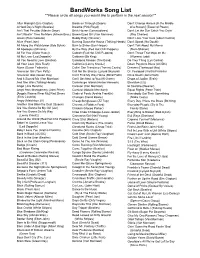

Bandworks Song List **Please Circle All Songs You Would Like to Perform in the Next Session**

BandWorks Song List **Please circle all songs you would like to perform in the next session** After Midnight (Eric Clapton) Break on Through (Doors) Don’t Change Horses [In the Middle A Hard Day’s Night (Beatles) Breathe (Pink Floyd) of a Stream] (Tower of Power) Ain’t That Peculiar (Marvin Gaye) Brick House (Commodores) Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Cryin’ Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More (Allman Bros.) Brown-Eyed Girl (Van Morrison) (Ray Charles) Alison (Elvis Costello) Buddy Holly (Weezer) Don’t Lose Your Cool (Albert Collins) Alive (Pearl Jam) Burning Down the House (Talking Heads) Don’t Speak (No Doubt) All Along the Watchtower (Bob Dylan) Burn to Shine (Ben Harper) Don’t Talk About My Mama All Apologies (Nirvana) By the Way (Red Hot Chili Peppers) (Mem Shanon) All For You (Sister Hazel) Cabron (Red Hot Chili Peppers) Don’t Throw That Mojo on Me All My Love (Led Zeppelin) Caldonia (Bb King) (Wynona Judd) All You Need Is Love (Beatles) Caledonia Mission (The Band) Do Your Thing (Lyn Collins) All Your Love (Otis Rush) California (Lenny Kravitz) Down Payment Blues (AC/DC) Alone (Susan Tedeschi) Callin’ San Francisco (Tommy Castro) Dreams (Fleetwood Mac) American Girl (Tom Petty) Call Me the Breeze (Lynyrd Skynyrd) Dr. Feelgood (Aretha Franklin) American Idiot (Green Day) Can’t Find My Way Home (Blind Faith) Drive South (John Hiatt) And It Stoned Me (Van Morrison) Can’t Get Next to You (Al Green) Drops of Jupiter (Train) And She Was (Talking Heads) Canteloupe Island (Herbie Hancock) Elevation (U2) Angel (Jimi Hendrix) Caravan (Van Morrison) -

The Herberts - SONGLIST Playing the Best of the 60S

The Herberts - SONGLIST Playing the best of the 60s Baby Please Don't Go Them *Gloria Them *Here Comes The Night Them *I'm A Man Spencer Davis Group Gimme Some Lovin' Spencer Davis Group Keep On Running Spencer Davis Group *She's So Fine Easybeats Women (Make You Feel Alright) Easybeats *St Louis Easybeats *Sorry Easybeats *I'll Make You Happy Easybeats Friday On My Mind Easybeats Wedding Ring Easybeats *Good Times Easybeats Green Onions Booker T and The MGs Time Is Tight Booker T and The MGs Mary Mary The Monkees *The Herberts Theme The Monkees I’m a Believer The Monkees Last Train to Clarksville The Monkees Steppin' Stone The Monkees Daydream Believer The Monkees *Hippy Hippy Shake Swinging Blue Jeans *You’re No Good Swinging Blue Jeans *She's Not There Zombies *Secret Agent Man The Guess Who Shakin' all Over The Guess Who *All Day and All of the Night Kinks *Dedicated Follower Of Fashion Kinks *Sunny Afternoon Kinks *You've Really Got Me Kinks *Tin Soldier The Small Faces *Itchycoo Park The Small Faces Pretty Woman Roy Orbison *Light My Fire Doors *All Over Now The Rolling Stones *Route 66 The Rolling Stones Walking The Dog The Rolling Stones *Get Off My Cloud The Rolling Stones Sympathy For The Devil The Rolling Stones Let’s Spend The Night Together The Rolling Stones (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones *When You Walk In The Room The Searchers *Sunshine Superman Donovan Mellow Yellow Donovan Good Lovin' The Young Rascals *I Feel Fine The Beatles *Twist and Shout The Beatles *Please Mr Postman The Beatles *Money The Beatles -

2020 Song List

2020 SONG LIST CURRENT 24K Magic - Bruno Mars Teenage Dream - Katy Perry All About That Bass - Megan Trainor That's Not My Name - The Ting Tings All I Do Is Win - DJ Khaled Tightrope - Janelle Monae American Boy - Estelle Tik Tok - Ke$ha Bad Guy - Billie Eilish Timber - Ke$ha Bang Bang - Ariana Grande & Jessie J Treasure - Bruno Mars Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke ft. Pharrell Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Cake By The Ocean - DNCE We Found Love - Rihanna Califonia Gurls - Katy Perry Wild Ones - Sia ft. Pitbull Can't Feel My Face - The Weeknd Yeah - Usher Can't Hold Us - Macklemore Can't Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Cheap Thrills - Sia ROCK Crazy - Gnarles Barkley Anyway You Want It - Journey Crazy In Love - Beyoncé Back In Black - AC/DC Don't Stop The Music - Rihanna Born In The USA - Bruce Springsteen Dynamite - Taio Cruz Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Feels - Pharrell & Katy Perry Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Feel It Still - Portugal. The Man Come On Eileen - Dexy Midnight Runner Feel This Moment - Christina ft. Pitbull Dancing With Myself - Billy Idol Firework - Katy Perry Dirty Laundry - Don Henley Get It Started - Black Eyed Peas Don't Stop Believing - Journey Get Lucky - Daft Punk ft. Pharrell Electric Feel - MGMT Girl On Fire - Alicia Keys Give It Away - Red Hot Chili Peppers Halo - Beyonce Honky Tonk Woman - Rolling Stones Happy - Pharrell I Saw Her Standing There - Beatles HandClap - Fitz & The Tantrums I Wanna Hold Your Hand - Beatles Havana - Camila Cabello Jessie's Girl - Rick Springfield Hella Good - No Doubt Jump - Van Halen Hey Ya - OutKast Jump Around - House of Pain Higher Love - Kygo/Whitney Houston Lay Down Sally - Eric Clapton I Gotta Feelin' - Black Eyed Peas Let's Dance - David Bowie I Like It - Enrique Iglesias Living On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Just Dance - Lady Gaga Love The One You're With - CS&N Locked Out Of Heaven - Bruno Mars Mony Mony - Billy Idol Love So Soft - Kelly Clarkson Moondance - Van Morrison Moves Like Jagger - Maroon 5 Paradise City - Guns n Roses On The Floor - J-Lo ft.