The Rosetta Stone in Historical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian Architects and Modern Egypt

1 AKPIA @ MIT - Studies on ARCHITECTURE, HISTORY & CULTURE Italian Architects and Modern Egypt Cristina Pallini “Exiles who, fleeing from the Pope or the Bourbons, had embarked at night in fishing boats from Barletta, or Taranto, or from the coast of Sic- ily, and after weeks at sea disembarked in Egypt. I imagined them, the legendary fugitives of the last century, wrapped in their cloaks, with wide-brimmed hats and long beards: they were mostly professional men or intellectuals who, after a while, sent for their wives from Italy or else married local girls. Later on their children and grandchildren . founded charitable institutions in Alexandria, the people’s university, the civil cem- etery. .” To the writer Fausta Cialente,1 these were the first Italians who crossed the Mediterranean in the first half of the nineteenth century to reach what had survived of trading outposts founded in the Middle Ages. Egypt, the meeting point between Africa and Asia, yet so accessible from Europe, was at that time the scene of fierce European rivalry. Within only a few years Mohamed Ali2 had assumed control of the corridors to India, pressing forward with industrial development based on cotton. Having lost no time in inducing him to abandon the conquered territories and revoke his monopoly regime, the Great Powers became competitors on a 1 Fausta Cialente (Cagliari 1898 – London 1994), Ballata levantina (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1961), 127–128. 2 Mohamed Ali (Kavala, Macedonia 1769 – Cairo 1849) is considered to be the founder of modern Egypt. His mark on the country’s history is due to his extensive political and military action, as well as his administrative, economic, and cultural reforms. -

Cleopatra II and III: the Queens of Ptolemy VI and VIII As Guarantors of Kingship and Rivals for Power

Originalveröffentlichung in: Andrea Jördens, Joachim Friedrich Quack (Hg.), Ägypten zwischen innerem Zwist und äußerem Druck. Die Zeit Ptolemaios’ VI. bis VIII. Internationales Symposion Heidelberg 16.-19.9.2007 (Philippika 45), Wiesbaden 2011, S. 58–76 Cleopatra II and III: The queens of Ptolemy VI and VIII as guarantors of kingship and rivals for power Martina Minas-Nerpel Introduction The second half of the Ptolemaic period was marked by power struggles not only among the male rulers of the dynasty, but also among its female members. Starting with Arsinoe II, the Ptolemaic queens had always been powerful and strong-willed and had been a decisive factor in domestic policy. From the death of Ptolemy V Epiphanes onwards, the queens controlled the political developments in Egypt to a still greater extent. Cleopatra II and especially Cleopatra III became all-dominant, in politics and in the ruler-cult, and they were often depicted in Egyptian temple- reliefs—more often than any of her dynastic predecessors and successors. Mother and/or daughter reigned with Ptolemy VI Philometor to Ptolemy X Alexander I, from 175 to 101 BC, that is, for a quarter of the entire Ptolemaic period. Egyptian queenship was complementary to kingship, both in dynastic and Ptolemaic Egypt: No queen could exist without a king, but at the same time the queen was a necessary component of kingship. According to Lana Troy, the pattern of Egyptian queenship “reflects the interaction of male and female as dualistic elements of the creative dynamics ”.1 The king and the queen functioned as the basic duality through which regeneration of the creative power of the kingship was accomplished. -

Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs the Ptolemaic Family In

Department of World Cultures University of Helsinki Helsinki Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs The Ptolemaic Family in the Encomiastic Poems of Callimachus Iiro Laukola ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV, University Main Building, on the 23rd of September, 2016 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 © Iiro Laukola 2016 ISBN 978-951-51-2383-1 (paperback.) ISBN 978-951-51-2384-8 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract The interaction between Greek and Egyptian cultural concepts has been an intense yet controversial topic in studies about Ptolemaic Egypt. The present study partakes in this discussion with an analysis of the encomiastic poems of Callimachus of Cyrene (c. 305 – c. 240 BC). The success of the Ptolemaic Dynasty is crystallized in the juxtaposing of the different roles of a Greek ǴdzȅǻǽǷȏȄ and of an Egyptian Pharaoh, and this study gives a glimpse of this political and ideological endeavour through the poetry of Callimachus. The contribution of the present work is to situate Callimachus in the core of the Ptolemaic court. Callimachus was a proponent of the Ptolemaic rule. By reappraising the traditional Greek beliefs, he examined the bicultural rule of the Ptolemies in his encomiastic poems. This work critically examines six Callimachean hymns, namely to Zeus, to Apollo, to Artemis, to Delos, to Athena and to Demeter together with the Victory of Berenice, the Lock of Berenice and the Ektheosis of Arsinoe. Characterized by ambiguous imagery, the hymns inspect the ruptures in Greek thought during the Hellenistic age. -

Kings & Events of the Babylonian, Persian and Greek Dynasties

KINGS AND EVENTS OF THE BABYLONIAN, PERSIAN, AND GREEK DYNASTIES 612 B.C. Nineveh falls to neo-Babylonian army (Nebuchadnezzar) 608 Pharaoh Necho II marched to Carchemesh to halt expansion of neo-Babylonian power Josiah, King of Judah, tries to stop him Death of Josiah and assumption of throne by his son, Jehoahaz Jehoiakim, another son of Josiah, replaced Jehoahaz on the authority of Pharaoh Necho II within 3 months Palestine and Syria under Egyptian rule Josiah’s reforms dissipate 605 Nabopolassar sends troops to fight remaining Assyrian army and the Egyptians at Carchemesh Nebuchadnezzar chased them all the way to the plains of Palestine Nebuchadnezzar got word of the death of his father (Nabopolassar) so he returned to Babylon to receive the crown On the way back he takes Daniel and other members of the royal family into exile 605 - 538 Babylon in control of Palestine, 597; 10,000 exiled to Babylon 586 Jerusalem and the temple destroyed and large deportation 582 Because Jewish guerilla fighters killed Gedaliah another last large deportation occurred SUCCESSORS OF NEBUCHADNEZZAR 562 - 560 Evil-Merodach released Jehoiakim (true Messianic line) from custody 560 - 556 Neriglissar 556 Labaski-Marduk reigned 556 - 539 Nabonidus: Spent most of the time building a temple to the mood god, Sin. This earned enmity of the priests of Marduk. Spent the rest of his time trying to put down revolts and stabilize the kingdom. He moved to Tema and left the affairs of state to his son, Belshazzar Belshazzar: Spent most of his time trying to restore order. Babylonia’s great threat was Media. -

Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota

Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers – the primary creative genius behind the famous British occult group, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn – and his wife Moina Mathers established a mystery religion of Isis in fin-de-siècle Paris. Lawrence Durdin-Robertson, his wife Pamela, and his sister Olivia created the Fellowship of Isis in Ireland in the early 1970s. Although separated by over half a century, and not directly associated with each other, both groups have several characteristics in common. Each combined their worship of an ancient Egyptian goddess with an interest in the Celtic Revival; both claimed that their priestly lineages derived directly from the Egyptian queen Scota, mythical foundress of Ireland and Scotland; and both groups used dramatic ritual and theatrical events as avenues for the promulgation of their Isis cults. The Parisian Isis movement and the Fellowship of Isis were (and are) historically-inaccurate syncretic constructions that utilised the tradition of an Egyptian origin of the peoples of Scotland and Ireland to legitimise their founders’ claims of lineal descent from an ancient Egyptian priesthood. To explore this contention, this chapter begins with brief overviews of Isis in antiquity, her later appeal for Enlightenment Freemasons, and her subsequent adoption by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. It then explores the Parisian cult of Isis, its relationship to the Celtic Revival, the myth of the Egyptian queen Scota, and examines the establishment of the Fellowship of Isis. The Parisian mysteries of Isis and the Fellowship of Isis have largely been overlooked by critical scholarship to date; the use of the medieval myth of Scota by the founders of these groups has hitherto been left unexplored. -

Raising of the Djed-Pillar

RAISING THE DJED PILLAR, THE RAMESSEUM DRAMATIC PAPYRUS Adapted by Stuart Tyson Smith from the translation & commentary of Kurt Sethe (1964, German translation by Jessika Akmenkalns), Henri Frankfort (1948), & Edward Wente (1980). Amenhotep III raises the Djed during his Heb-Sed in the tomb of Kheruef at Thebes. The annual ritual of “Raising the Djed” was the culmination of the larger “Mysteries of Osiris,” which commemorated the resurrection of Osiris after his murder by Seth and the restoration of the throne to Osiris’s son Horus. During the Coronation and Heb-Sed festival, Pharaoh took the place of Horus in the ritual, emphasizing the stability of his rule and his connection with the Osiris myth. Its phallic overtones alluded to the renewal of Pharaoh’s potency as ruler like Osiris in the myth. The Djed appears already in Predynastic art and was probably originally a fetish consisting of a pole with sheaves of grain attached. The Djed is described later on as the “Backbone of Osiris” in the Book of the Dead, but the original harvest and renewal symbolism was retained in the ritual. Although probably originally part of Ptah’s cult, the two gods were associated through a syncretism with Sokar, and the ceremony resonated with Osiris’s role as a god of the agricultural cycle. Cast: Lector Priest, Thoth, Geb, Horus/the King, Children of Horus, Osiris (as the Djed), Seth, Isis, Nephthys, Descendants of the King/Followers of Horus/Great Ones of Lower Egypt (royal princes and princesses), Musicians, Dancers and Singers, Followers of Seth/Great Ones of Upper Egypt, Spirit Seekers and the Keeper of the Two Feathers. -

Seminary Studies

ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES VOLUME VI JANUARI 1968 NUMBER I CONTENTS Heimmerly-Dupuy, Daniel, Some Observations on the Assyro- Babylonian and Sumerian Flood Stories Hasel, Gerhard F., Sabbatarian Anabaptists of the Sixteenth Century: Part II 19 Horn, Siegfried H., Where and When was the Aramaic Saqqara Papyrus Written ? 29 Lewis, Richard B., Ignatius and the "Lord's Day" 46 Neuffer, Julia, The Accession of Artaxerxes I 6o Specht, Walter F., The Use of Italics in English Versions of the New Testament 88 Book Reviews iio ANDREWS UNIVERSITY BERRIEN SPRINGS, MICHIGAN 49104, USA ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES The Journal of the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary of Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan SIEGFRIED H. HORN Editor EARLE HILGERT KENNETH A. STRAND Associate Editors LEONA G. RUNNING Editorial Assistant SAKAE Kos() Book Review Editor ROY E. BRANSON Circulation Manager ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES publishes papers and short notes in English, French and German on the follow- ing subjects: Biblical linguistics and its cognates, textual criticism, exegesis, Biblical archaeology and geography, an- cient history, church history, theology, philosophy of religion, ethics and comparative religions. The opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the editors. ANDREWS UNIVERSITY SEMINARY STUDIES is published in January and July of each year. The annual subscription rate is $4.00. Payments are to be made to Andrews University Seminary Studies, Berrien Springs, Michigan 49104, USA. Subscribers should give full name and postal address when paying their subscriptions and should send notice of change of address at least five weeks before it is to take effect; the old as well as the new address must be given. -

Souls of Mischief: ’93 Still Infinity Tour Hits Pawtucket

Souls of Mischief: ’93 Still Infinity Tour Hits Pawtucket The Met played host to the Souls of Mischief during their 20-year anniversary tour of their legendary debut album, “’93 til Infinity”. This Oakland-based hip- hop group, comprised of four life-long friends, A-Plus, Tajai, Opio and Phesto, together has created one of the most influential anthems of the ‘90’s hip-hop movement: the title track of the album, ’93 ‘til Infinity. This song is a timeless classic. It has a simple, but beautifully melodic beat that works seamlessly with the song’s message of promoting peace, friendship and of course, chillin’. A perfect message to kick off a summer of music with. The crowd early on in the night was pretty thin and the supporting acts did their best to amp up the audience for the Souls of Mischief. When they took the stage at midnight, the shift in energy was astounding. They walked out on stage and the waning crowd filled the room in seconds. The group was completely unfazed by the relatively small showing and instead, connected with the crowd and how excited they were to be in Pawtucket, RI of all places. Tajai, specifically, reminisced about his youth and his precious G.I. Joes (made by Hasbro) coming from someplace called Pawtucket and how “souped” he was to finally come through. The show was a blissful ride through the group’s history, mixing classic tracks like “Cab Fare” with more recent releases, like “Tour Stories”. The four emcees seamlessly passed around the mic and to the crowd’s enjoyment, dropped a song from their well-known hip-hop super-group, Hieroglyphics, which includes the likes of Casual, Del Tha Funkee Homosapien and more. -

PDF Fulltext

BENHA VETERINARY MEDICAL JOURNAL, VOL. 23, NO. 1, JUNE 2012: 123- 130 BENHA UNIVERSITY BENHA VETERINARY MEDICAL JOURNAL FACULTY OF VETERINARY MEDICINE PREVALENCE OF BOVINE VIRAL DIARRHEA VIRUS (BVDV) IN CATTLE FROM SOME GOVERNORATES IN EGYPT. El-Bagoury G.F.a, El-Habbaa A.S.a, Nawal M.A.b and Khadr K.A.c aVirology Dept., Fac. Vet. Med., Benha University, Benha, bAnimal Health Research Institute (AHRI), Dokki- c Giza, General Organization for Veterinary Medicine (GOVS), Dokki-Giza, Egypt. A B S T R A C T Diagnosis of the BVDV infection among suspected and apparently healthy cattle at Kaluobia, Giza, Menofeia and Gharbia governorates was done by detection of prevalence of BVD antibodies. A total number of 151/151(100%) and 97/151 (62.25%) of examined sera were positive for BVD antibodies using serum neutralization test (SNT) and competitive immunoenzymatic assay (cIEA), respectively. Examined sera with cIEA detected antibodies against BVDV non structral proteins P80/P125. Detection of BVDV in buffy coat samples using antigen capture ELISA showed that 22/151(14.56%) of the samples were positive for BVDV. Isolation and biotyping of suspected BVDV from buffy coat on MDBK cell line showed that 19/22 of ELISA positive buffy coat samples were cytopathogenic BVDV biotype (cpBVDV) while only 3/22 samples were CPE negative suggesting a non- cytopathogenic BVDV (ncpBVDV) biotype. Inoculated cell culture with no CPE were subjected to IFAT and IPMA using specific antisera against BVDV revealed positive results indicating presence of non-cytopathogenic strain of BVDV. It was concluded that cIEA detected antibodies against non- structural proteins P80/P125 has many advantages over SNT being for rapid diagnosis of BVDV. -

International Journal of Fuzzy System Applications

InternatIonal Journal of fuzzy SyStem applIcatIonS October-December 2013, Vol. 3, No. 4 Table of Contents Special Issue: Fuzzy and Rough Hybrid Intelligent Techniques in Medical Diagnosis iv Guest Editor Preface Ahmad Taher Azar, Faculty of Computers and Information, Benha University, Benha, Egypt Aboul Ella Hassanien, Scientific Research Group in Egypt (SRGE), Faculty of Computers and Information, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt Research Articles 1 Rough ISODATA Algorithm S. Sampath, Department of Statistics, University of Madras, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India B. Ramya, Department of Statistics, University of Madras, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India 15 Hybrid Tolerance Rough Set: PSO Based Supervised Feature Selection for Digital Mammogram Images G. Jothi, Department of IT, Sona College of Technology (Autonomous), Salem, Tamil Nadu, India H. Hannah Inbarani, Department of Computer Science, Periyar University, Salem, Tamil Nadu, India Ahmad Taher Azar, Faculty of Computers and Information, Benha University, Banha, Egypt 31 Hybrid System based on Rough Sets and Genetic Algorithms for Medical Data Classifications Hanaa Ismail Elshazly, Scientific Research Group in Egypt (SRGE), Faculty of Computers and Information, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt Ahmad Taher Azar, Faculty of Computers and Information, Benha University, Benha, Egypt Aboul Ella Hassanien, Scientific Research Group in Egypt (SRGE), Faculty of Computers and Information, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt Abeer Mohamed Elkorany, Faculty of Computers and Information, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt -

The Ptolemies: an Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. Contributions to a Different Perspective and Approach

THE PTOLEMIES: AN UNLOVED AND UNKNOWN DYNASTY. CONTRIBUTIONS TO A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE AND APPROACH JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES Universidade Aberta. Centro de História (University of Lisbon). Abstract: The fifteen Ptolemies that sat on the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (the date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII) are in most cases little known and, even in its most recognised bibliography, their work has been somewhat overlooked, unappreciated. Although boisterous and sometimes unloved, with the tumultuous and dissolute lives, their unbridled and unrepressed ambitions, the intrigues, the betrayals, the fratricides and the crimes that the members of this dynasty encouraged and practiced, the Ptolemies changed the Egyptian life in some aspects and were responsible for the last Pharaonic monuments which were left us, some of them still considered true masterpieces of Egyptian greatness. The Ptolemaic Period was indeed a paradoxical moment in the History of ancient Egypt, as it was with a genetically foreign dynasty (traditions, language, religion and culture) that the country, with its capital in Alexandria, met a considerable economic prosperity, a significant political and military power and an intense intellectual activity, and finally became part of the world and Mediterranean culture. The fifteen Ptolemies that succeeded to the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII), after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, are, in most cases, very poorly understood by the public and even in the literature on the topic. -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

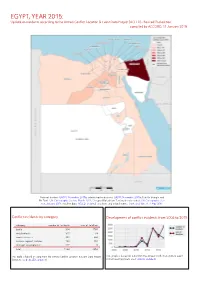

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha.