Punctuated Equilibrium: a Model for Administrative Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Punctuated Equilibrium Theory Variations in Punctuated Equilibrium and and the Diffusion of Innovation

An Introduction to Punctuated Equilibrium: A Model for Understanding Stability and Dramatic Change in Public Policies January 2018 This briefing note belongs to a series on the Tobacco policies can serve as an example to various models used in political science to illustrate this idea. Up until 1965, this policy had represent public policy development processes. changed very little, whereas in the late 1960s and Each of these briefing notes begins by describing early 1970s a radical change occurred in the analytical framework proposed by the given response to the actions of certain stakeholders, model. With this model in mind, we then set out to such as the US Surgeon General's 1964 examine questions that public health actors might publication of the now-famous report entitled ask about public policies. Our aim in these notes Smoking and Health. is not to further refine existing models; nor is it to advocate for the adoption of one model in To incorporate their insight into public policy particular. Our purpose is rather to suggest how analysis, Baumgartner and Jones sought to each of these models constitutes a useful reconcile in an integrated model the long periods interpretive lens that can guide reflection and of equilibrium, already well explained by the action leading to the production of healthy public incrementalist model, and the abrupt policies. punctuations of political systems. This became known as the punctuated equilibrium model. The punctuated equilibrium model aims to explain why public policies tend to be characterized by long periods of stability punctuated by short periods of radical change. -

V Sem Zool Punctuated Equilibrium

V Sem Zool Punctuated Equilibrium Gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are two ways in which the evolution of a species can occur. A species can evolve by only one of these, or by both. Scientists think that species with a shorter evolution evolved mostly by punctuated equilibrium, and those with a longer evolution evolved mostly by gradualism. Both phyletic gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are speciation theory and are valid models for understanding macroevolution. Both theories describe the rates of speciation. For Gradualism, changes in species is slow and gradual, occurring in small periodic changes in the gene pool, whereas for Punctuated Equilibrium, evolution occurs in spurts of relatively rapid change with long periods of non-change. The gradualism model depicts evolution as a slow steady process in which organisms change and develop slowly over time. In contrast, the punctuated equilibrium model depicts evolution as long periods of no evolutionary change followed by rapid periods of change. Both are models for describing successive evolutionary changes due to the mechanisms of evolution in a time frame. Punctuated equilibrium The punctuated equilibrium hypothesis states that speciation events occur rapidly in geological time - over hundreds of thousands to millions of years and that little change occurs in the time between speciation events. In other words, change only happens under certain conditions, and it happens rapidly. Instead of a slow, continuous movement, evolution tends to be characterized by long periods of virtual standstill or equilibrium punctuated by episodes of very fast development of new forms. It was proposed by Eldridge and Gould to explain the gaps in the fossil record - the fact that the fossil record does not show smooth evolutionary transitions. -

Punctuated Equilibrium Models in Organizational Decision Making 135

1 2 Punctuated Equilibrium Models 3 4 8 5 in Organizational Decision 6 7 Making 8 9 10 Scott E. Robinson 11 12 13 14 CONTENTS 15 16 8.1 Two Research Conundrums..................................................................................................134 17 8.1.1 Lindblom’s Theory of Administrative Incrementalism...........................................134 18 8.1.2 Wildavsky’s Theory of Budgetary Incrementalism.................................................135 19 8.1.3 The Diverse Meanings of Budgetary “Incrementalism”..........................................135 20 8.1.4 A Brief Aside on Paleontology.................................................................................136 21 8.2 Punctuated Equilibrium Theory—A Way Out of Both Conundrums.................................136 22 8.3 A Theoretical Model of Punctuated Equilibrium Theory....................................................137 23 8.4 Evidence of Punctuated Equilibria in Organizational Decision Making ............................139 24 8.4.1 Punctuated Equilibrium and the Federal Budget.....................................................139 25 8.4.2 Punctuated Equilibrium and Local Government Budgets.......................................140 26 8.4.3 Punctuated Equilibrium and the Federal Policy Process.........................................141 27 8.4.4 Punctuated Equilibrium and Organizational Bureaucratization ..............................142 28 8.4.5 Assessing the Evidence.............................................................................................143 -

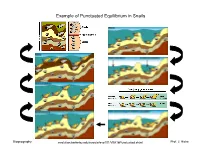

Example of Punctuated Equilibrium in Snails

Example of Punctuated Equilibrium in Snails Biogeography evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/evo101/VIIA1bPunctuated.shtml1 Prof. J. Hicke Punctuated Equilibrium Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 2 Prof. J. Hicke Allopatric Speciation http://wps.pearsoncustom.com/wps/media/objects/3014/3087289/Web_Tutorials/18_A01.swf Biogeography 3 Prof. J. Hicke Allopatric Speciation: Vicariance Event Biogeography 4 Prof. J. Hicke Allopatric speciation, founder event Genes rare in original population are dominant in founding population Biogeography 5 Prof. J. Hicke Sympatric and Parapatric Speciation sympatric: extensive overlap parapatric: minimal overlap (partial geographic separation) Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 6 Prof. J. Hicke Parapatric Speciation No extrinsic barrier to gene flow, but… 1. restricted gene flow within population 2. varying selective pressures across the population range “Although continuously distributed, different flowering times have begun to reduce gene flow between metal-tolerant plants and metal-intolerant plants. “ evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/evo101/VC1dParapatric.shtml Biogeography 7 Prof. J. Hicke Example of Sympatric Speciation • 200 years ago, flies only on hawthorns • then, introduction of domestic apple • females lay eggs on type of fruit they grew up on; males look for mates on type of fruit they grew up on • restricted gene flow • speciation http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/evo101/VC1eSympatric.shtml Biogeography 8 Prof. J. Hicke Example of Sympatric Speciation Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 9 Prof. J. Hicke Adaptive Radiation often rapid speciation: Lake Victoria: 100s of new species in <12,000 years Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 10 Prof. J. Hicke Adaptive Radiation www.micro.utexas.edu/courses/levin/bio304/evolution/speciation.html Biogeography 11 Prof. -

Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) All Sprouts Content Sprouts 4-1-2008 Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information System Development and Change: Towards a Socio-Technical Process Analysis Kalle Lyytinen Case Western Reserve University, [email protected] Mike Newman Agder University College Follow this and additional works at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/sprouts_all Recommended Citation Lyytinen, Kalle and Newman, Mike, " Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information System Development and Change: Towards a Socio-Technical Process Analysis" (2008). All Sprouts Content. 120. http://aisel.aisnet.org/sprouts_all/120 This material is brought to you by the Sprouts at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in All Sprouts Content by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Working Papers on Information Systems ISSN 1535-6078 Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information System Development and Change: Towards a Socio-Technical Process Analysis Kalle Lyytinen Case Western Reserve University, USA Mike Newman Agder University College, Norway Abstract We view information system development (ISD) and change as a socio-technical change process in which technologies, human actors, organizational relationships and tasks change. We outline a punctuated socio-technical change model that recognizes both incremental and dynamic and abrupt changes during ISD and change. The model identifies events that incrementally change the information system as well as punctuate its deep structure in its evolutionary path at multiple levels. The analysis of these event sequences helps explain how and why an ISD outcome emerged. -

Evolution in the Weak-Mutation Limit: Stasis Periods Punctuated by Fast Transitions Between Saddle Points on the Fitness Landscape

Evolution in the weak-mutation limit: Stasis periods punctuated by fast transitions between saddle points on the fitness landscape Yuri Bakhtina, Mikhail I. Katsnelsonb, Yuri I. Wolfc, and Eugene V. Kooninc,1 aCourant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York University, New York, NY 10012; bInstitute for Molecules and Materials, Radboud University, NL-6525 AJ Nijmegen, The Netherlands; and cNational Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20894 Contributed by Eugene V. Koonin, December 16, 2020 (sent for review July 24, 2020; reviewed by Sergey Gavrilets and Alexey S. Kondrashov) A mathematical analysis of the evolution of a large population occur (9, 10). The long intervals of stasis are punctuated by short under the weak-mutation limit shows that such a population periods of rapid evolution during which speciation occurs, and the would spend most of the time in stasis in the vicinity of saddle previous dominant species is replaced by a new one. Gould and points on the fitness landscape. The periods of stasis are punctu- Eldredge emphasized that PE was not equivalent to the “hopeful ated by fast transitions, in lnNe/s time (Ne, effective population monsters” idea, in that no macromutation or saltation was proposed size; s, selection coefficient of a mutation), when a new beneficial to occur, but rather a major acceleration of evolution via rapid mutation is fixed in the evolving population, which accordingly succession of “regular” mutations that resulted in the appearance of moves to a different saddle, or on much rarer occasions from a instantaneous speciation, on a geological scale. -

Punctuated Equilibrium Vs. Phyletic Gradualism

International Journal of Bio-Science and Bio-Technology Vol. 3, No. 4, December, 2011 Punctuated Equilibrium vs. Phyletic Gradualism Monalie C. Saylo1, Cheryl C. Escoton1 and Micah M. Saylo2 1 University of Antique, Sibalom, Antique, Philippines 2 DepEd Sibalom North District, Sibalom, Antique, Philippines [email protected] Abstract Both phyletic gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are speciation theory and are valid models for understanding macroevolution. Both theories describe the rates of speciation. For Gradualism, changes in species is slow and gradual, occurring in small periodic changes in the gene pool, whereas for Punctuated Equilibrium, evolution occurs in spurts of relatively rapid change with long periods of non-change. The gradualism model depicts evolution as a slow steady process in which organisms change and develop slowly over time. In contrast, the punctuated equilibrium model depicts evolution as long periods of no evolutionary change followed by rapid periods of change. Both are models for describing successive evolutionary changes due to the mechanisms of evolution in a time frame. Keywords: macroevolution, phyletic gradualism, punctuated equilibrium, speciation, evolutionary change 1. Introduction Has the evolution of life proceeded as a gradual stepwise process, or through relatively long periods of stasis punctuated by short periods of rapid evolution? To date, what is clear is that both evolutionary patterns – phyletic gradualism and punctuated equilibrium have played at least some role in the evolution of life. Gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are two ways in which the evolution of a species can occur. A species can evolve by only one of these, or by both. Scientists think that species with a shorter evolution evolved mostly by punctuated equilibrium, and those with a longer evolution evolved mostly by gradualism. -

Speciation and Bursts of Evolution

Evo Edu Outreach (2008) 1:274–280 DOI 10.1007/s12052-008-0049-4 ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Speciation and Bursts of Evolution Chris Venditti & Mark Pagel Published online: 5 June 2008 # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2008 Abstract A longstanding debate in evolutionary biology Darwin’s gradualistic view of evolution has become widely concerns whether species diverge gradually through time or accepted and deeply carved into biological thinking. by rapid punctuational bursts at the time of speciation. The Over 110 years after Darwin introduced the idea of natural theory of punctuated equilibrium states that evolutionary selection in his book The Origin of Species, two young change is characterised by short periods of rapid evolution paleontologists put forward a controversial new theory of the followed by longer periods of stasis in which no change tempo and mode of evolutionary change. Niles Eldredge and occurs. Despite years of work seeking evidence for Stephen Jay Gould’s(Eldredge1971; Eldredge and Gould punctuational change in the fossil record, the theory 1972)theoryofPunctuated Equilibria questioned Darwin’s remains contentious. Further there is little consensus as to gradualistic account of evolution, asserting that the majority the size of the contribution of punctuational changes to of evolutionary change occurs at or around the time of overall evolutionary divergence. Here we review recent speciation. They further suggested that very little change developments which show that punctuational evolution is occurred between speciation events—aphenomenonthey common and widespread in gene sequence data. referred to as evolutionary stasis. Eldredge and Gould had arrived at their theory by Keywords Speciation . Evolution . Phylogeny. -

A Punctuated-Equilibrium Model of Technology Diffusion

A Punctuated-Equilibrium Model of Technology Diffusion Christoph H. Loch Bernardo A. Huberman INSEAD Xerox PARC Fontainebleau, France Palo Alto, CA 94304 Revised, December 1997 Abstract We present an evolutionary model of technology diffusion in which an old and a new technology are available, both of which improve their performance incrementally over time. Technology adopters make repeated choices between the established and the new technology based on their perceived performance, which is subject to uncertainty. Both technologies exhibit positive externalities, or performance benefits from others using the same technology. We find that the superior technology will not necessarily be broadly adopted by the population. Externalities cause two stable usage equilibria to exist, one with the old technology being the standard and the other with the new technology the standard. Punctuations, or sudden shifts, in these equilibria determine the patterns of technology diffusion. The time for an equilibrium punctuation depends on the rate of incremental improvement of both technologies, and on the system’s resistance to switching between equilibria. If the new technology has a higher rate of incremental improvement, it is adopted faster, and adoption may precede performance parity if the system’s resistance to switching is low. Adoption of the new technology may trail performance parity if the system’s resistance to switching is high. The authors thank two anonymous referees for very helpful comments on a previous version of this article. This research was financially supported by Xerox PARC and by the INSEAD R&D fund. 1. Introduction In the age of gene technology, superconductors and supercomputers, it is often claimed that innovations are mainly breakthroughs from existing technologies. -

Concepts of Punctuated Equilibrium, Concerted Evolution and Coevolution

Journal of Scientific Research Vol. 58, 2014 : 15-26 Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi ISSN : 0447-9483 EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY : CONCEPTS OF PUNCTUATED EQUILIBRIUM, CONCERTED EVOLUTION AND COEVOLUTION Bashisth N. Singh Genetics Laboratory, Department of Zoology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005 [email protected] Abstract For more than a century, evolution has become a corner stone of biology. In the middle of the last century, Ernst Mayr established Evolutionary Biology as a separate field of studies in USA. In 1744, Haller, a Swiss biologist coined the term ’Evolutio’ (a Latin word for Evolution) which means to unroll or unfold. It was used to describe the progressive unfolding of structures during development. In the middle of nineteenth century, Herbert Spencer, an English Philosopher popularized the word Evolution. He has also been called as Father of Social Darwinism. His idea about evolution was influenced by both Lamarckism and Darwinism. From time to time, various theories have been proposed to explain the mechanisms of evolution. These theories are: Lamarckism, Darwinism, theory of germplasm, isolation theory, mutation theory, synthetic theory and neutral theory. These theories except synthetic theory explain the mechanisms of evolution by giving more emphasis on single factor. However, the modern synthetic theory which was developed by the contributions of many evolutionary biologists, combines many factors in one theory and is widely accepted theory of evolution. There exists controversy between neutralists vs. selectionists. Further, Lamarckism (theory of inheritance of acquired characters) has been rejected and is of only historical significance. In the last century, a few new concepts of evolutionary biology were proposed by evolutionary biologists. -

Darwin, Wallace, and Evolution by Natural Selection

BIOL 300 – Foundations of Biology Summer 2017 – Telleen Lecture Outline Evolution and Natural Selection I. What is Evolution? A. Changes over time, building on past and current features 1. Products evolve 2. Knowledge evolves 3. Beliefs evolve B. Evolutionary patterns in biology have been noted as far back as Aristotle C. Patterns of biological evolution have been observed in three major areas: 1. Anatomical features 2. Fossil records 3. Molecular distances II. Evolution: Getting from There to Here A. The word ‘evolution’ refers to how entities change through time B. In Western culture, the concept of evolution of species goes back to Aristotle C. In other cultures and religions, evolution plays a central role (e.g. Taoism) D. The concept of evolution helps explain the great paradox of biology: In life there exists both unity and diversity E. Darwin initially used the phrase “descent with modification” to explain the concept of evolution F. Prior to Darwin and Wallace, it was widely thought that biological evolution occurred by inheritance of acquired characteristics. More specifically, individuals passed on to offspring body and behavior changes acquired during their lives G. In contrast, Darwin and Wallace proposed that: Variation is an inherent characteristic of all biological populations It is not created by experience. This is readily observable in populations. III. The Rate of Evolution A. Different kinds of organisms do evolve at different rates B. For example, bacteria evolve much faster than eukaryotes C. The rate of evolution also differs within the same group of species D. Evolution can occur in spurts, which is called punctuated equilibrium E. -

Evolution Lesson 8.4: Macroevolution and the Origin of Species Lesson

Chapter 8: Evolution Lesson 8.4: Macroevolution and the Origin of Species Fast or slow? Which is better, the direct route or the scenic route? Each has its advantages, depending on the situation. And that describes evolution. It can be fast or slow, depending on the situation. Lesson Objectives • Describe two ways that new species may originate. • Differentiate between allopatric, peripatric, parapatric, and sympatric speciation. • Identify the different patterns of macroevolution • Distinguish between gradualism and punctuated equilibrium. • Understand the concept of extinction and how it affects evolution. Vocabulary • allopatric speciation • behavioral isolation • coevolution • convergent evolution • divergent evolution • geographic isolation • gradualism • parapatric speciation • peripatric speciation • punctuated equilibrium • speciation • sympatric speciation • temporal isolation Introduction Macroevolution is evolution over geologic time above the level of the species. One of the main topics in macroevolution is how new species arise. The process by which a new species evolves is called speciation. How does speciation occur? How does one species evolve into two or more new species? 275 Origin of Species To understand how a new species forms, it’s important to review what a species is. A species is a group of organisms that can breed and produce fertile offspring together in nature. For a new species to arise, some members of a species must become reproductively isolated from the rest of the species. This means they can no longer interbreed with other members of the species. How does this happen? Usually they become geographically isolated first. The macroevolution of a species happens as a result of speciation. Speciation is the branching off of individuals from the species they originally were.