Punctuated Equilibrium Theory Simply Extends Current Agenda- Setting Theories to Deal with Both Policy Stasis, Or Incrementalism, and Policy Punctuations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Punctuated Equilibrium Theory Variations in Punctuated Equilibrium and and the Diffusion of Innovation

An Introduction to Punctuated Equilibrium: A Model for Understanding Stability and Dramatic Change in Public Policies January 2018 This briefing note belongs to a series on the Tobacco policies can serve as an example to various models used in political science to illustrate this idea. Up until 1965, this policy had represent public policy development processes. changed very little, whereas in the late 1960s and Each of these briefing notes begins by describing early 1970s a radical change occurred in the analytical framework proposed by the given response to the actions of certain stakeholders, model. With this model in mind, we then set out to such as the US Surgeon General's 1964 examine questions that public health actors might publication of the now-famous report entitled ask about public policies. Our aim in these notes Smoking and Health. is not to further refine existing models; nor is it to advocate for the adoption of one model in To incorporate their insight into public policy particular. Our purpose is rather to suggest how analysis, Baumgartner and Jones sought to each of these models constitutes a useful reconcile in an integrated model the long periods interpretive lens that can guide reflection and of equilibrium, already well explained by the action leading to the production of healthy public incrementalist model, and the abrupt policies. punctuations of political systems. This became known as the punctuated equilibrium model. The punctuated equilibrium model aims to explain why public policies tend to be characterized by long periods of stability punctuated by short periods of radical change. -

Decision Mode, Information and Network Attachment in the Internationalization of Smes: a Configurational and Contingency Analysis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Child, John; Hsieh, Linda H. Y. Working Paper Decision mode, information and network attachment in the internationalization of SMEs: A configurational and contingency analysis Birmingham Business School Discussion Paper Series, No. 2013-09 Provided in Cooperation with: Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham Suggested Citation: Child, John; Hsieh, Linda H. Y. (2013) : Decision mode, information and network attachment in the internationalization of SMEs: A configurational and contingency analysis, Birmingham Business School Discussion Paper Series, No. 2013-09, University of Birmingham, Birmingham Business School, Birmingham, http://epapers.bham.ac.uk/1770/ This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/202653 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

V Sem Zool Punctuated Equilibrium

V Sem Zool Punctuated Equilibrium Gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are two ways in which the evolution of a species can occur. A species can evolve by only one of these, or by both. Scientists think that species with a shorter evolution evolved mostly by punctuated equilibrium, and those with a longer evolution evolved mostly by gradualism. Both phyletic gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are speciation theory and are valid models for understanding macroevolution. Both theories describe the rates of speciation. For Gradualism, changes in species is slow and gradual, occurring in small periodic changes in the gene pool, whereas for Punctuated Equilibrium, evolution occurs in spurts of relatively rapid change with long periods of non-change. The gradualism model depicts evolution as a slow steady process in which organisms change and develop slowly over time. In contrast, the punctuated equilibrium model depicts evolution as long periods of no evolutionary change followed by rapid periods of change. Both are models for describing successive evolutionary changes due to the mechanisms of evolution in a time frame. Punctuated equilibrium The punctuated equilibrium hypothesis states that speciation events occur rapidly in geological time - over hundreds of thousands to millions of years and that little change occurs in the time between speciation events. In other words, change only happens under certain conditions, and it happens rapidly. Instead of a slow, continuous movement, evolution tends to be characterized by long periods of virtual standstill or equilibrium punctuated by episodes of very fast development of new forms. It was proposed by Eldridge and Gould to explain the gaps in the fossil record - the fact that the fossil record does not show smooth evolutionary transitions. -

Incrementalism Redux: State Roles in Local Government Fiscal Crises∗

Incrementalism Redux: State Roles in Local Government Fiscal Crises∗ Presented by: Beth Walter Honadle Director, Institute for Policy Research, and Professor, Political Science University of Cincinnati ∗ Presented at the 59th International Atlantic Economic Conference, London, England, March 12, 2005. The author gratefully acknowledges the C. P. Taft Memorial Fund for an international conference travel grant, which allowed her to present this paper at the conference. She also appreciates assistance on preparing the manuscript from Yana Keck, a graduate student at the University of Cincinnati working at the Institute for Policy Research. Incrementalism Redux: State Roles in Local Government Fiscal Crises Beth Walter Honadle Abstract State governments in the U. S. have a major stake in the fiscal health and condition of local governments inasmuch as local fiscal emergencies can adversely impact the states’ finances and, to the extent that local services receive state funding, the states want to ensure responsible management of state funds. This paper contributes to understanding how states have developed their roles relative to this ostensibly local governmental issue. Drawing on survey data collected by the author, this paper examines how states have developed their roles relative to local government fiscal crises. The generic state-level roles that the study explored are: to predict, to avert, to mitigate, and to prevent recurrence of local government fiscal crises. Taken as a whole, these roles are assumed to approximate the rational- -

Punctuated Equilibrium Models in Organizational Decision Making 135

1 2 Punctuated Equilibrium Models 3 4 8 5 in Organizational Decision 6 7 Making 8 9 10 Scott E. Robinson 11 12 13 14 CONTENTS 15 16 8.1 Two Research Conundrums..................................................................................................134 17 8.1.1 Lindblom’s Theory of Administrative Incrementalism...........................................134 18 8.1.2 Wildavsky’s Theory of Budgetary Incrementalism.................................................135 19 8.1.3 The Diverse Meanings of Budgetary “Incrementalism”..........................................135 20 8.1.4 A Brief Aside on Paleontology.................................................................................136 21 8.2 Punctuated Equilibrium Theory—A Way Out of Both Conundrums.................................136 22 8.3 A Theoretical Model of Punctuated Equilibrium Theory....................................................137 23 8.4 Evidence of Punctuated Equilibria in Organizational Decision Making ............................139 24 8.4.1 Punctuated Equilibrium and the Federal Budget.....................................................139 25 8.4.2 Punctuated Equilibrium and Local Government Budgets.......................................140 26 8.4.3 Punctuated Equilibrium and the Federal Policy Process.........................................141 27 8.4.4 Punctuated Equilibrium and Organizational Bureaucratization ..............................142 28 8.4.5 Assessing the Evidence.............................................................................................143 -

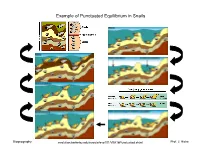

Example of Punctuated Equilibrium in Snails

Example of Punctuated Equilibrium in Snails Biogeography evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/evo101/VIIA1bPunctuated.shtml1 Prof. J. Hicke Punctuated Equilibrium Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 2 Prof. J. Hicke Allopatric Speciation http://wps.pearsoncustom.com/wps/media/objects/3014/3087289/Web_Tutorials/18_A01.swf Biogeography 3 Prof. J. Hicke Allopatric Speciation: Vicariance Event Biogeography 4 Prof. J. Hicke Allopatric speciation, founder event Genes rare in original population are dominant in founding population Biogeography 5 Prof. J. Hicke Sympatric and Parapatric Speciation sympatric: extensive overlap parapatric: minimal overlap (partial geographic separation) Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 6 Prof. J. Hicke Parapatric Speciation No extrinsic barrier to gene flow, but… 1. restricted gene flow within population 2. varying selective pressures across the population range “Although continuously distributed, different flowering times have begun to reduce gene flow between metal-tolerant plants and metal-intolerant plants. “ evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/evo101/VC1dParapatric.shtml Biogeography 7 Prof. J. Hicke Example of Sympatric Speciation • 200 years ago, flies only on hawthorns • then, introduction of domestic apple • females lay eggs on type of fruit they grew up on; males look for mates on type of fruit they grew up on • restricted gene flow • speciation http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/evo101/VC1eSympatric.shtml Biogeography 8 Prof. J. Hicke Example of Sympatric Speciation Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 9 Prof. J. Hicke Adaptive Radiation often rapid speciation: Lake Victoria: 100s of new species in <12,000 years Lomolino et al. , 2006 Biogeography 10 Prof. J. Hicke Adaptive Radiation www.micro.utexas.edu/courses/levin/bio304/evolution/speciation.html Biogeography 11 Prof. -

Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) All Sprouts Content Sprouts 4-1-2008 Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information System Development and Change: Towards a Socio-Technical Process Analysis Kalle Lyytinen Case Western Reserve University, [email protected] Mike Newman Agder University College Follow this and additional works at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/sprouts_all Recommended Citation Lyytinen, Kalle and Newman, Mike, " Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information System Development and Change: Towards a Socio-Technical Process Analysis" (2008). All Sprouts Content. 120. http://aisel.aisnet.org/sprouts_all/120 This material is brought to you by the Sprouts at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in All Sprouts Content by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Working Papers on Information Systems ISSN 1535-6078 Punctuated Equilibrium, Process Models and Information System Development and Change: Towards a Socio-Technical Process Analysis Kalle Lyytinen Case Western Reserve University, USA Mike Newman Agder University College, Norway Abstract We view information system development (ISD) and change as a socio-technical change process in which technologies, human actors, organizational relationships and tasks change. We outline a punctuated socio-technical change model that recognizes both incremental and dynamic and abrupt changes during ISD and change. The model identifies events that incrementally change the information system as well as punctuate its deep structure in its evolutionary path at multiple levels. The analysis of these event sequences helps explain how and why an ISD outcome emerged. -

Evolution in the Weak-Mutation Limit: Stasis Periods Punctuated by Fast Transitions Between Saddle Points on the Fitness Landscape

Evolution in the weak-mutation limit: Stasis periods punctuated by fast transitions between saddle points on the fitness landscape Yuri Bakhtina, Mikhail I. Katsnelsonb, Yuri I. Wolfc, and Eugene V. Kooninc,1 aCourant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York University, New York, NY 10012; bInstitute for Molecules and Materials, Radboud University, NL-6525 AJ Nijmegen, The Netherlands; and cNational Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20894 Contributed by Eugene V. Koonin, December 16, 2020 (sent for review July 24, 2020; reviewed by Sergey Gavrilets and Alexey S. Kondrashov) A mathematical analysis of the evolution of a large population occur (9, 10). The long intervals of stasis are punctuated by short under the weak-mutation limit shows that such a population periods of rapid evolution during which speciation occurs, and the would spend most of the time in stasis in the vicinity of saddle previous dominant species is replaced by a new one. Gould and points on the fitness landscape. The periods of stasis are punctu- Eldredge emphasized that PE was not equivalent to the “hopeful ated by fast transitions, in lnNe/s time (Ne, effective population monsters” idea, in that no macromutation or saltation was proposed size; s, selection coefficient of a mutation), when a new beneficial to occur, but rather a major acceleration of evolution via rapid mutation is fixed in the evolving population, which accordingly succession of “regular” mutations that resulted in the appearance of moves to a different saddle, or on much rarer occasions from a instantaneous speciation, on a geological scale. -

Punctuated Equilibrium Vs. Phyletic Gradualism

International Journal of Bio-Science and Bio-Technology Vol. 3, No. 4, December, 2011 Punctuated Equilibrium vs. Phyletic Gradualism Monalie C. Saylo1, Cheryl C. Escoton1 and Micah M. Saylo2 1 University of Antique, Sibalom, Antique, Philippines 2 DepEd Sibalom North District, Sibalom, Antique, Philippines [email protected] Abstract Both phyletic gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are speciation theory and are valid models for understanding macroevolution. Both theories describe the rates of speciation. For Gradualism, changes in species is slow and gradual, occurring in small periodic changes in the gene pool, whereas for Punctuated Equilibrium, evolution occurs in spurts of relatively rapid change with long periods of non-change. The gradualism model depicts evolution as a slow steady process in which organisms change and develop slowly over time. In contrast, the punctuated equilibrium model depicts evolution as long periods of no evolutionary change followed by rapid periods of change. Both are models for describing successive evolutionary changes due to the mechanisms of evolution in a time frame. Keywords: macroevolution, phyletic gradualism, punctuated equilibrium, speciation, evolutionary change 1. Introduction Has the evolution of life proceeded as a gradual stepwise process, or through relatively long periods of stasis punctuated by short periods of rapid evolution? To date, what is clear is that both evolutionary patterns – phyletic gradualism and punctuated equilibrium have played at least some role in the evolution of life. Gradualism and punctuated equilibrium are two ways in which the evolution of a species can occur. A species can evolve by only one of these, or by both. Scientists think that species with a shorter evolution evolved mostly by punctuated equilibrium, and those with a longer evolution evolved mostly by gradualism. -

Speciation and Bursts of Evolution

Evo Edu Outreach (2008) 1:274–280 DOI 10.1007/s12052-008-0049-4 ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Speciation and Bursts of Evolution Chris Venditti & Mark Pagel Published online: 5 June 2008 # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2008 Abstract A longstanding debate in evolutionary biology Darwin’s gradualistic view of evolution has become widely concerns whether species diverge gradually through time or accepted and deeply carved into biological thinking. by rapid punctuational bursts at the time of speciation. The Over 110 years after Darwin introduced the idea of natural theory of punctuated equilibrium states that evolutionary selection in his book The Origin of Species, two young change is characterised by short periods of rapid evolution paleontologists put forward a controversial new theory of the followed by longer periods of stasis in which no change tempo and mode of evolutionary change. Niles Eldredge and occurs. Despite years of work seeking evidence for Stephen Jay Gould’s(Eldredge1971; Eldredge and Gould punctuational change in the fossil record, the theory 1972)theoryofPunctuated Equilibria questioned Darwin’s remains contentious. Further there is little consensus as to gradualistic account of evolution, asserting that the majority the size of the contribution of punctuational changes to of evolutionary change occurs at or around the time of overall evolutionary divergence. Here we review recent speciation. They further suggested that very little change developments which show that punctuational evolution is occurred between speciation events—aphenomenonthey common and widespread in gene sequence data. referred to as evolutionary stasis. Eldredge and Gould had arrived at their theory by Keywords Speciation . Evolution . Phylogeny. -

Service Infusion As Agile Incrementalism in Action

Service infusion as agile incrementalism in action Christian Kowalkowski, Daniel Kindström, Thomas Brashear Alejandro, Staffan Brege and Sergio Biggemann Linköping University Post Print N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. Original Publication: Christian Kowalkowski, Daniel Kindström, Thomas Brashear Alejandro, Staffan Brege and Sergio Biggemann, Service infusion as agile incrementalism in action, 2012, Journal of Business Research, (65), 6, 765-772. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.12.014 Copyright: Elsevier http://www.elsevier.com/ Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-77120 Service Infusion as Agile Incrementalism in Action Christian Kowalkowski, Linköping University Daniel Kindström, Linköping University Thomas Brashear Alejandro, University of Massachusetts Amherst Staffan Brege, Linköping University Sergio Biggemann, University of Otago The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Jan Wallander and Tom Hedelius Foundation and Vinnova (The Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems). Trenchant comments by David Ballantyne, University of Otago, and Christina Grundström, Linköping University, to an earlier draft were very helpful in revising the paper. The authors alone are responsible for all limitations and errors that may relate to the study and the paper. Send correspondence to Christian Kowalkowski, Linköping University, Department of Management and Engineering, SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden; telephone: -

A Punctuated-Equilibrium Model of Technology Diffusion

A Punctuated-Equilibrium Model of Technology Diffusion Christoph H. Loch Bernardo A. Huberman INSEAD Xerox PARC Fontainebleau, France Palo Alto, CA 94304 Revised, December 1997 Abstract We present an evolutionary model of technology diffusion in which an old and a new technology are available, both of which improve their performance incrementally over time. Technology adopters make repeated choices between the established and the new technology based on their perceived performance, which is subject to uncertainty. Both technologies exhibit positive externalities, or performance benefits from others using the same technology. We find that the superior technology will not necessarily be broadly adopted by the population. Externalities cause two stable usage equilibria to exist, one with the old technology being the standard and the other with the new technology the standard. Punctuations, or sudden shifts, in these equilibria determine the patterns of technology diffusion. The time for an equilibrium punctuation depends on the rate of incremental improvement of both technologies, and on the system’s resistance to switching between equilibria. If the new technology has a higher rate of incremental improvement, it is adopted faster, and adoption may precede performance parity if the system’s resistance to switching is low. Adoption of the new technology may trail performance parity if the system’s resistance to switching is high. The authors thank two anonymous referees for very helpful comments on a previous version of this article. This research was financially supported by Xerox PARC and by the INSEAD R&D fund. 1. Introduction In the age of gene technology, superconductors and supercomputers, it is often claimed that innovations are mainly breakthroughs from existing technologies.