The Limits of Compassion and Risk Management in Toronto School Safety from 1999-2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministry of Health and Long Term

Ministry of Health Ministÿre de la Santd and Long-Term Care et des Soins de Iongue durde 11 .l(k) Office of the Minister Bureau du ministre 10th Floor, Hepburn Block 10e 6tage, ÿdifice Hepburn 80 Grosvenor Street 80, rue Grosvenor Toronto ON M7A 2C4 Toronto ON M7A 2C4 Tel 416-327-4300 T61 416-327-4300 Fax 416-326-1571 T61ÿc 416-326-1571 www.health.gov.on.ca www.health.gov.on.ca H LTC2976 FL-2011-174 AUG 2 3 2011 Mr. Bob Bratina Chair City of Hamilton Board of Health Hamilton City Hall 2nd Floor - 71 Main Street West Hamilton ON L8P 4Y5 Dear Ms.ÿBraÿ: .ÿ I am pleased to advise you that the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care will provide City of Hamilton Board of Health new base funding of up to $116,699 to support the implementation of the Chief Nursing Officer (CNO) initiative, including the creation of a new position with responsibilities for nursing quality assurance and nursing practice leadership. This investment is part of the 9,000 Nurses Commitment, a key component of the province's health human resources strategy, HealthForceOntario. The funding of up to $29,175 will be provided this calendar year covering the period from October to December 2011. Funding will be annualized up to $116,699 in the 2012 funding year. The establishment of CNOs in public health units will enhance public health nursing practice, professional development, and quality assurance for public health programs and services delivered by public health nurses. Public Health CNOs will provide public health nursing leadership and oversee practice development activities to strengthen the public health nursing workforce which in turn, will contribute to positive health outcomes for individuals, groups and populations in communities across Ontario. -

The Informer

Bill 65 passed on May 10, 2000 during the 37th Session, founded the Ontario Association of Former Parliamentarians. It was the first Bill in Ontario history to be introduced by a Legislative Committee. ONTARIO ASSOCIATION OF FORMER PARLIMENTARIANS SUMMER 2017 Bill 65 passed on May 10, 2000 during the 37th Session, founded the Ontario Association of Former Parliamentarians. It was the first Bill in Ontario history to be introduced by a Legislative Committee. SUMMER 2017 Table Of Contents Interview: Leona Dombrowsky Page 3 Interview: Steve Mahoney Page 5 Obituary: Gerry Martiniuk Page 8 AGM Recap Page 10 Hugh O’Neil Frienship Garden Page 11 Interview: Bill Murdoch Page 13 Interview: Phil Gillies Page 16 Interview: Sharon Murdock Page 19 Interview: Rolando P. Vera Rodas Page 21 Ceremonial Flag Raising Area Page 23 Margaret Campbell Page 24 Tributes Page 26 Contact Us Page 27 2 Bill 65 passed on May 10, 2000 during the 37th Session, founded the Ontario Association of Former Parliamentarians. It was the first Bill in Ontario history to be introduced by a Legislative Committee. Interview: Leona Dombrowsky M. P. P. Liberal, Cabinet Minister Hastings-Frontenac-Lennox and Addington 1999-2007 Prince Edward-Hastings 2007-2011 “It is critical to have an understanding that everything we do has an impact, either positive or negative on the environment.” Leona Dombrowsky’s interest in politics started with dinner table talk when she was young. While her parents were not involved in partisan politics, they were always interested in the issues of the day and hence Leona, growing up in the French Settlement north of Tweed, developed an interest in politics. -

A Bittersweet Day for Stryi Omits Patriarchal Issue, for Now Town Mourns One Hierarch and Celebrates Another

INSIDE: • The Kuchma inquiry: about murder or politics? – page 3. • Community honors Montreal journalist – page 8. • “Garden Party” raises $14,000 for Plast camp – page 10. THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal Wnon-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXIX No. 15 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, APRIL 10, 2011 $1/$2 in Ukraine Meeting with pope, UGCC leader A bittersweet day for Stryi omits patriarchal issue, for now Town mourns one hierarch and celebrates another that we are that Church which is devel- oping, and each Eastern Church which is developing is moving towards a patri- archate, because a patriarchate is a natu- ral completion of the development of this Church,” the major archbishop said at his first official press conference, held on March 29. He was referring to the Synod of Bishops held March 21-24. The sudden reversal revealed that the otherwise talented major archbishop has already begun the process of learning the ropes of politics and the media, as indi- cated by both clergy and laity. Major Archbishop Shevchuk was accompanied by several bishops on his five-day visit to Rome, including Archbishop-Metropolitan Stefan Soroka of the Philadelphia Archeparchy, Bishop Paul Patrick Chomnycky of the Stamford Eparchy, and Bishop Ken Nowakowski Zenon Zawada of the New Westminster Eparchy. Father Andrii Soroka (left) of Poland and Bishop Taras Senkiv lead the funeral The entourage of bishops agreed that procession in Stryi on March 26 for Bishop Yulian Gbur. raising the issue of a patriarchate – when presenting the major archbishop for the by Zenon Zawada Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk. -

Ontario Gazette Volume 140 Issue 43, La Gazette De L'ontario Volume 140

Vol. 140-43 Toronto ISSN 0030-2937 Saturday, 27 October 2007 Le samedi 27 octobre 2007 Proclamation ELIZABETH THE SECOND, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom, ELIZABETH DEUX, par la grâce de Dieu, Reine du Royaume-Uni, du Canada and Her other Realms and Territories, Queen, Head of the Canada et de ses autres royaumes et territoires, Chef du Commonwealth, Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. Défenseur de la Foi. Family Day, the third Monday of February of every year, is declared a Le jour de la Famille, troisième lundi du mois de février de chaque année, holiday, pursuant to the Retail Business Holidays Act, R.S.O. 1990, est déclaré jour férié conformément à la Loi sur les jours fériés dans le Chapter R.30 and of the Legislation Act, 2006, S.O. 2006 c. 21 Sched. F. commerce de détail, L.R.O. 1990, chap. R.30, et à la Loi de 2006 sur la législation, L.O. 2006, chap. 21, ann. F. WITNESS: TÉMOIN: THE HONOURABLE L’HONORABLE DAVID C. ONLEY DAVID C. ONLEY LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR OF OUR LIEUTENANT-GOUVERNEUR DE NOTRE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO PROVINCE DE L’ONTARIO GIVEN at Toronto, Ontario, on October 12, 2007. FAIT à Toronto (Ontario) le 12 octobre 2007. BY COMMAND PAR ORDRE DAVID CAPLAN DAVID CAPLAN Minister of Government Services (140-G576) ministre des Services gouvernementaux Parliamentary Notice Avis parlementaire RETURN OF MEMBER ÉLECTIONS DES DÉPUTÉS Notice is Hereby Given of the receipt of the return of members on Nous accusons réception par la présente des résultats du scrutin, or after the twenty-sixth day of October, 2007, to represent -

Kitchener, ON

MEDIA RELEASE: Immediate REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY OF WATERLOO COUNCIL AGENDA Wednesday, February 28, 2001 6:45 p.m. Closed 7:00 p.m. Regular REGIONAL COUNCIL CHAMBER 150 Frederick Street, Kitchener, ON * DENOTES CHANGES TO, OR ITEMS NOT PART OF ORIGINAL AGENDA 1. MOMENT OF SILENCE 2. ROLL CALL 3. MOTION TO GO INTO CLOSED SESSION (if necessary) 4. MOTION TO RECONVENE IN OPEN SESSION (if necessary) 5. DECLARATION OF PECUNIARY INTEREST UNDER THE MUNICIPAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST ACT 6. PRESENTATIONS a) Alison Jackson, Friends of Doon Heritage Crossroads re: Cheque Presentation. b) Lloyd Wright, Chair of Joint Executive Committee re: Update on Hospital Redevelopment Plan. 7. DELEGATIONS a) Don Pavey, Cambridge Cycling Committee re: funding for construction of bike lanes, Cambridge. *b) Albert Ashley, Waterloo re: budget for cycling facilities. c) Mike Connolly, Waterloo re: 2001 Budget. d) Grants 1) Maureen Jordan, Serena K-W 2) Mary Heide-Miller, Serena K-W 3) Tony Jordan, Serena K-W 4) Steve Woodworth, K-W Right To Life 5) Jessica Ling, K-W Right To Life 6) Jane Richard, K-W Right To Life 7) Jolanta Scott, Planned Parenthood 8) Bruce Milne, Planned Parenthood - 2 - *9) Diane Wagner, Planned Parenthood * Refer to Community Health Department Issue Paper immediately following Page 4 of the Agenda. 10) Robert Achtemichuk, Executive Director, Waterloo Regional Arts Council 11) Isabella Stefanescu, Art Works *12) Jennifer Watson, Epilepsy Waterloo-Wellington re: funding. *13) Wayne McDonald, Chair Development Committee, Leadership Waterloo Region re: funding. *14) Margaret Bauer-Hoel, Executive Director, Volunteer Action Centre re: funding. *e) Craig Hawthorne, Halt 7 re: funding for transportation. -

Do Good Intentions Beget Good Policy? Two Steps Forward and One Step Back in the Construction of Domestic Violence in Ontario

Do Good Intentions Beget Good Policy? Two Steps Forward and One Step Back in the Construction of Domestic Violence in Ontario by April Lucille Girard-Brown A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen‟s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada January, 2012 Copyright ©April Lucille Girard-Brown, 2012 Abstract The construction of domestic violence shifted and changed as this issue was forced from the private shadows to the public stage. This dissertation explores how government policy initiatives - Bill 117: An Act to Better Protect Victims of Domestic Violence and the Domestic Violence Action Plan (DVAP) - shaped our understanding of domestic violence as a social problem in the first decade of the twenty-first century in Ontario. Specifically, it asks whose voices were heard, whose were silenced, how domestic violence was conceptualized by various stakeholders. In order to do this I analyzed the texts of Bill 117, its debates, the DVAP, as well as fourteen in-depth interviews with anti- violence advocates in Ontario to shed light on their construction of the domestic violence problem. Then I examined who (both state and non-state actors) regarded the work as „successful‟, flawed or wholly ineffective. In particular, I focused on the claims and counter-claims advanced by MPPs, other government officials, feminist or other women‟s group advocates and men‟s or fathers‟ rights group supporters and organizations. The key themes derived from the textual analysis of documents and the interviews encapsulate the key issues which formed the dominant construction of domestic violence in Ontario between 2000 and 2009: the never-ending struggles over funding, debates surrounding issues of rights and responsibilities, solutions proposed to address domestic violence, and finally the continued appearance of deserving and undeserving victims in public policy. -

Readers Say Marijuana Growing Concern

--> Bob Aaron [email protected] July 30, 2005 Readers say marijuana growing concern Judging from the flood of emails and faxes I received following my July 9, 2005 Title Page column ("Grow house disclosure is critical," archived at http://aaron.ca/columns/2005-07-09.htm), it seems that the issue of disclosure of grow house operations on police web sites and in agreements of purchase and sale is quite a hot topic among real estate stakeholders. I suggested in the column that the Toronto police should list known grow house locations on their web site. I also suggested that a warranty clause that a property has never been used as a grow operation become part of the standard form used for Ontario house purchases. I pointed out that police websites in Winnipeg and London, Ont., list locations where search warrants have led to the seizure of marijuana plants. Along the lines of my suggestions, back in March, Cambridge MPP Gerry Martiniuk introduced a private member's bill at Queen's Park. Bill 181, the Protection Against Illicit Grow Houses Act, 2005, would require a vendor to reveal in any agreement of purchase and sale if the building or structure has been used to grow any illicit drugs. Peter Boesener, of Top to Bottom Inspections in Brampton, emailed to say that he has seen his share of grow houses. One house he inspected recently had been totally cleaned up and the local police wouldn't reveal anything about its history. After the new owners moved in, they discovered it had been a grow house and busted by the police several months earlier. -

View the Full Digital Edition

You Go Beyond. So Do We. The career of a teacher is one of educating, informing and most of all caring. Everyday teachers go beyond the call of duty, company you can trust. Our comprehensive line helping students solve problems, build their futures of insurance products are specifically designed and make wise decisions. At Teachers Life, we’re with educators in mind. teachers too. Like you, we go beyond the call of duty to ensure your future, and your family’s, is At Teachers Life we want to help you make as secure as it can be. We are the only insurance informed and judicious decisions about your company founded and run by teachers, and have insurance protection. We can assist you in providing been for 65 years. We are an insurance company, insurance solutions for income replacement, not a brokerage firm, which means you deal pension maximization, mortgage insurance and with us directly for all your insurance and supplemental coverage. Contact us today and one claims needs. As a not-for-profit organization of our professional customer service associates will responsible to our clients not shareholders, you evaluate your personal situation and discuss which can be rest assured that you are dealing with a insurance options best meet your individual needs. 1.800.668.4229 or 416.620.1140 Teachers Life' 1939-2004 - 65 Years of Dedicated Service! TEACHERS LIFE INSURANCE SOCIETY (FRATERNAL)™ La societe d’assurance-vie des enseignantes et enseignants (fraternelle)™ Email: [email protected] Website: www.teacherslife.c om Features Departments Lesson Plans ETFO's 2002/2003 Scholarship 3. -

ALPHABETICAL LISTING of ONTARIO MEMBERS of PROVINCIAL PARLIAMENT at MARCH 20, 2007

ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF ONTARIO MEMBERS OF PROVINCIAL PARLIAMENT at MARCH 20, 2007 Member of Provincial Parliament Riding Email Ted Arnott Waterloo-Wellington [email protected] Wayne Arthurs Pickering-Ajax-Uxbridge [email protected] Bas Balkissoon Scarborough-Rouge River [email protected] Toby Barrett Haldimand-Norfolk-Brant [email protected] Hon Rick Bartolucci Sudbury [email protected] Hon Christopher Bentley London West [email protected] Lorenzo Berardinetti Scarborough Southwest [email protected] Gilles Bisson Timmins-James Bay [email protected] Hon Marie Bountrogianni Hamilton Mountain [email protected] Hon James J. Bradley St. Catharines [email protected] Hon Laurel C. Broten Etobicoke-Lakeshore [email protected] Michael A. Brown Algoma-Manitoulin [email protected] Jim Brownell Stormont-Dundas-Charlottenburgh [email protected] Hon Michael Bryant St. Paul's [email protected] Hon David Caplan Don Valley East [email protected] Hon Donna H. Cansfield Etobicoke Centre [email protected] Hon Mary Anne V. Chambers Scarborough East [email protected] Hon Michael Chan Markham [email protected] Ted Chudleigh Halton [email protected] Hon Mike Colle Eglinton-Lawrence [email protected] Kim Craitor Niagara Falls [email protected] Bruce Crozier Essex [email protected] Bob Delaney Mississauga West [email protected] Vic Dhillon Brampton West-Mississauga [email protected] Hon Caroline Di Cocco Sarnia-Lambton [email protected] Cheri DiNovo Parkdale-High Park [email protected] Hon Leona Dombrowsky Hastings-Frontenac-Lennox & Addington [email protected] Brad Duguid Scarborough Centre [email protected] Hon Dwight Duncan Windsor-St. -

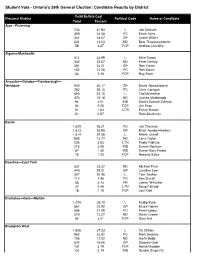

Candidate Results W Late Results

Student Vote - Ontario's 39th General Election: Candidate Results by District Valid Ballots Cast Electoral District Political Code Name of Candidate Total Percent Ajax—Pickering 743 41.93 L Joe Dickson 409 23.08 PC Kevin Ashe 331 18.67 GP Cecile Willert 231 13.03 ND Bala Thavarajasoorier 58 3.27 FCP Andrew Carvalho Algoma-Manitoulin 514 33.99 L Mike Brown 432 28.57 ND Peter Denley 351 23.21 GP Ron Yurick 152 10.05 PC Ron Swain 63 4.16 FCP Ray Scott Ancaster—Dundas—Flamborough— Westdale 940 30.17 GP David Januczkowski 782 25.10 PC Chris Corrigan 690 22.15 L Ted Mcmeekin 473 15.18 ND Juanita Maldonado 94 3.01 IND Martin Samuel Zuliniak 64 2.05 FCP Jim Enos 51 1.63 COR Eileen Butson 21 0.67 Sam Zaslavsky Barrie 1,629 26.21 PC Joe Tascona 1,613 25.95 GP Erich Jacoby-Hawkins 1,514 24.36 L Aileen Carroll 856 13.77 ND Larry Taylor 226 3.63 LTN Paolo Fabrizio 215 3.45 IND Darren Roskam 87 1.39 IND Daniel Gary Predie 75 1.20 FCP Roberto Sales Beaches—East York 531 35.37 ND Michael Prue 440 29.31 GP Caroline Law 307 20.45 L Tom Teahen 112 7.46 PC Don Duvall 56 3.73 FR James Whitaker 37 2.46 LTN Doug Patfield 18 1.19 FCP Joel Kidd Bramalea—Gore—Malton 1,079 38.70 L Kuldip Kular 667 23.92 GP Bruce Haines 588 21.09 PC Pam Hundal 370 13.27 ND Glenn Crowe 84 3.01 FCP Gary Nail Brampton West 1,526 37.23 L Vic Dhillon 962 23.47 PC Mark Beckles 706 17.22 ND Garth Bobb 642 15.66 GP Sanjeev Goel 131 3.19 FCP Norah Madden 131 3.19 IND Gurdial Singh Fiji Brampton—Springdale 1,057 33.95 ND Mani Singh 983 31.57 L Linda Jeffrey 497 15.96 PC Carman Mcclelland -

633058129179308750 Christop

By Christopher Twardawa [email protected] To be presented to the Ontario Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform January 2007 Version ONE-070.131 www.ctess.ca www.TwardawaModel.org Any opinion or view presented in the document is that of and only of the author, Christopher Twardawa, and may not necessarily reflect those of any organization he is or has been associated with. Reproduction of this document in whole or in part is permitted, provided the source (Christopher Twardawa and www.ctess.ca or www.TwardawaModel.org ) is fully acknowledged. © Christopher Twardawa, 2007 TwardawaModel.org CTESS.ca Sometimes the simplest solution is the best. Christopher Twardawa Electoral System Solution ii TwardawaModel.org CTESS.ca About CTESS The Christopher Twardawa Electoral System Solution (CTESS) is the creation of its author – Christopher Twardawa and is designed to provide a better electoral system than what Canada and its provinces now have. With the belief that the current system is good but requires improvements, CTESS strengthens it by identifying deficiencies and proposing innovations. Unlike any other electoral system currently in use and which all have tradeoffs, CTESS has no tradeoffs and therefore eliminates the need to change electoral systems as a whole. Christopher first started thinking about this after the 1993 Canadian federal elections, since the results of those elections appeared to him to be inconsistent with how the voters voted. Ten years later in 2003, while still in university, he came up with the current model (the Twardawa Model) which is a simple yet considerate and sophisticated model. It can be applied to any democratic state under the Westminster model of government and similar systems. -

Two Women Honoured at Awards Gala

THE GRAND STRATEGY NEWSLETTER Volume 12, Number 6 - Nov/Dec. 2007 Grand River The Grand: Conservation A Canadian Authority Heritage River 2007 Awards Gala Betty Schneider 1 Marilyn Murray 2 Milestones Grand Commission celebrates 75th 2 Water Forum 2007 3 Grand River history symposium 6 Two women honoured at awards gala Look Who’s Taking Action wo women who have played leading roles in A 1967 headline in the Kitchener Waterloo GeoTime trail 7 Tconservation efforts in the Grand River Record proclaimed, “Betty’s a Woman of many Pedestrian bridge 7 watershed were honoured at a special gala firsts” while a photo caption declares she is evening at the River Run Centre in Guelph in used to being the only woman in a crowd and What’s Happening October. shows a photo of her touring Conestogo Dam Betty Schneider of Waterloo received a with other authority offi- Eleventh heritage day workshop 7 standing ovation after she was presented with a cials. Watershed Honour Roll Award by the Grand “If anyone’s apt to Now Available River Conservation Authority. The award, restore your faith in the which is not given out each year, was for her power of the individual in Grand Registry 7 many years of support for the GRCA, the today’s supposedly demo- Grand River Conservation Foundation and cratic society it’s Mrs. What You Can Do many community conservation projects. Herbert Schneider, mother Bottled water 8 Schneider served on the GRCA board for 11 Betty Schneider of four children,” the article years beginning in 1966 and was its first declared.