633058129179308750 Christop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mon 18 Apr 2005 / Lun 18 Avr 2005

No. 130A No 130A ISSN 1180-2987 Legislative Assembly Assemblée législative of Ontario de l’Ontario First Session, 38th Parliament Première session, 38e législature Official Report Journal of Debates des débats (Hansard) (Hansard) Monday 18 April 2005 Lundi 18 avril 2005 Speaker Président Honourable Alvin Curling L’honorable Alvin Curling Clerk Greffier Claude L. DesRosiers Claude L. DesRosiers Hansard on the Internet Le Journal des débats sur Internet Hansard and other documents of the Legislative Assembly L’adresse pour faire paraître sur votre ordinateur personnel can be on your personal computer within hours after each le Journal et d’autres documents de l’Assemblée législative sitting. The address is: en quelques heures seulement après la séance est : http://www.ontla.on.ca/ Index inquiries Renseignements sur l’index Reference to a cumulative index of previous issues may be Adressez vos questions portant sur des numéros précédents obtained by calling the Hansard Reporting Service indexing du Journal des débats au personnel de l’index, qui vous staff at 416-325-7410 or 325-3708. fourniront des références aux pages dans l’index cumulatif, en composant le 416-325-7410 ou le 325-3708. Copies of Hansard Exemplaires du Journal Information regarding purchase of copies of Hansard may Pour des exemplaires, veuillez prendre contact avec be obtained from Publications Ontario, Management Board Publications Ontario, Secrétariat du Conseil de gestion, Secretariat, 50 Grosvenor Street, Toronto, Ontario, M7A 50 rue Grosvenor, Toronto (Ontario) M7A 1N8. Par 1N8. Phone 416-326-5310, 326-5311 or toll-free téléphone : 416-326-5310, 326-5311, ou sans frais : 1-800-668-9938. -

V119-1985To1986-331.Pdf

I LyJL^JJLK p <4- Ontario JOURNALS OF THE Legislative Assembly OF THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO From 4th of June to 18th of June 1985 Both Days Inclusive and from 2nd of July to 12th of July 1985 Both Days Inclusive and from 15th of October to 20th of December 1985 Both Days Inclusive and from 6th of January to 12th of February 1986 Both Days Inclusive IN THE THIRTY-FOURTH AND THIRTY-FIFTH YEAR OF THE REIGN OF OUR SOVEREIGN LADY QUEEN ELIZABETH II BEING THE First Session of the Thirty-Third Parliament of Ontario SESSION 1985-86 VOL. CXIX INDEX Journals of the Legislative Assembly, Ontario 34-35 ELIZABETH II, 1985-86 1st Session Thirty-Third Parliament DJOURNMENT DEBATES: July 9 (two matters), July 11, November 5 (two matters), December 5 (two matters), December 10 (two matters), December 12 (two matters), Decem- ber 19, January 7, 21 , 23, 28. Aexander, Honourable Lincoln: Appointment as Lieutenant Governor remarks on, (Oct. 15), 71. gOARD OF INTERNAL ECONOMY: Order-in-Council re membership of, (June 7, July 5, Oct. 28, Dec. 9), 26. 46. 92, 144. Budget Debate: 1. Motion for approval, (Oct. 24), 87. Carried, (Feb. 12), 232. Amendment moved, (Oct. 25), 90. Lost, (Feb. 12), 231. 2. Dates debated October 24, 25, 28, 29, 31, November 1 , 4, February 12. By-Election: Warrant for issued, (Oct. 15), 71. fiiil iv index 1985-86 1 ABINET OFFICE ESTIMATES: Cabinet Office Programme. Deemed reported and concurred in (Feb. 12), 221. Francophone Affairs Programme see Francophone Affairs. Commission on Redistribution: Debate on the motion for Consideration of Objections to the Report of (July 5, Oct. -

A Canadian Model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A

Proportional-first-past-the-post: A Canadian model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador May 2014 ii Abstract For more than a decade a majority of Canadians have consistently supported the idea of proportional representation when asked, yet all attempts at electoral reform thus far have failed. Even though a majority of Canadians support proportional representation, a majority also report they are satisfied with the current electoral system (even indicating support for both in the same survey). The author seeks to reconcile these potentially conflicting desires by designing a uniquely Canadian electoral system that keeps the positive and familiar features of first-past-the- post while creating a proportional election result. The author touches on the theory of representative democracy and its relationship with proportional representation before delving into the mechanics of electoral systems. He surveys some of the major electoral system proposals and options for Canada before finally presenting his made-in-Canada solution that he believes stands a better chance at gaining approval from Canadians than past proposals. iii Acknowledgements First of foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my brilliant supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner, whose continuous guidance, support, and advice over the past few years has been invaluable. I am especially grateful to you for encouraging me to pursue my Master’s and write about my electoral system idea. -

Table of Contents/Table De Matières

Comptes publics de l’ Public Accounts of Ministry Ministère of des Finance Finances PUBLIC COMPTES ONTARIOONTARIO ACCOUNTS PUBLICS of de ONTARIO L’ONTARIO This publication is available in English and French. CD-ROM copies in either language may be obtained from: ServiceOntario Publications Telephone: (416) 326-5300 Toll-free: 1-800-668-9938 2011–2012 TTY Toll-free: 1-800-268-7095 Website: www.serviceontario.ca/publications For electronic access, visit the Ministry of Finance website at www.fin.gov.on.ca Le présent document est publié en français et en anglais. 2011-2012 On peut en obtenir une version sur CD-ROM dans l’une ou l’autre langue auprès de : D E TA I L E D S C H E D U L E S Publications ServiceOntario Téléphone : 416 326-5300 Sans frais : 1 800 668-9938 O F P AY M E N T S Téléimprimeur (ATS) sans frais : 1 800 268-7095 Site Web : www.serviceontario.ca/publications Pour en obtenir une version électronique, il suffit de consulter le site Web du ministère des Finances à www.fin.gov.on.ca D ÉTAILS DES PAIEMENTS © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2012 © Imprimeur de la Reine pour l’Ontario, 2012 ISSN 0381-2375 (Print) / ISSN 0833-1189 (Imprimé) ISSN 1913-5556 (Online) / ISSN 1913-5564 (En ligne) Volume 3 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DE MATIÈRES Page General/Généralités Guide to Public Accounts.................................................................................................................................. 3 Guide d’interprétation des comptes publics ...................................................................................................... 5 MINISTRY STATEMENTS/ÉTATS DES MINISTÈRES Aboriginal Affairs/Affaires autochtones ........................................................................................................... 7 Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs/Agriculture, Alimentation et Affaires rurales......................................... -

Report of the Select Committee on Electoral Reform

Legislative Assemblée Assembly législative of Ontario de l'Ontario SELECT COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL REFORM REPORT ON ELECTORAL REFORM 2nd Session, 38th Parliament 54 Elizabeth II Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Ontario. Legislative Assembly. Select Committee on Electoral Reform Report on electoral reform [electronic resource] Issued also in French under title: Rapport de la réforme électorale. Electronic monograph in PDF format. Mode of access: World Wide Web. ISBN 0-7794-9375-3 1. Ontario. Legislative Assembly—Elections. 2. Elections—Ontario. 3. Voting—Ontario. I. Title. JL278 O56 2005 324.6’3’09713 C2005-964015-4 Legislative Assemblée Assembly législative of Ontario de l'Ontario The Honourable Mike Brown, M.P.P., Speaker of the Legislative Assembly. Sir, Your Select Committee on Electoral Reform has the honour to present its Report and commends it to the House. Caroline Di Cocco, M.P.P., Chair. Queen's Park November 2005 SELECT COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL REFORM COMITÉ SPÉCIAL DE LA RÉFORME ÉLECTORALE Room 1405, Whitney Block, Toronto, Ontario M7A 1A2 SELECT COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL REFORM MEMBERSHIP LIST CAROLINE DI COCCO Chair NORM MILLER Vice-Chair WAYNE ARTHURS KULDIP S. KULAR RICHARD PATTEN MICHAEL D. PRUE MONIQUE M. SMITH NORMAN STERLING KATHLEEN O. WYNNE Anne Stokes Clerk of the Committee Larry Johnston Research Officer i CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Electoral Systems 1 Citizens’ Assembly Terms of Reference 2 Composition of the Assembly 2 Referendum Issues 4 Review of Electoral Reform 5 Future Role 5 List of Recommendations 6 INTRODUCTION 9 Mandate 9 Research Methodology 10 Assessment Criteria 10 Future Role 11 Acknowledgements 11 I. -

District Name

District name Name Party name Email Phone Algoma-Manitoulin Michael Mantha New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1938 Bramalea-Gore-Malton Jagmeet Singh New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1784 Essex Taras Natyshak New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0714 Hamilton Centre Andrea Horwath New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-7116 Hamilton East-Stoney Creek Paul Miller New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0707 Hamilton Mountain Monique Taylor New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1796 Kenora-Rainy River Sarah Campbell New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2750 Kitchener-Waterloo Catherine Fife New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6913 London West Peggy Sattler New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6908 London-Fanshawe Teresa J. Armstrong New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1872 Niagara Falls Wayne Gates New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 212-6102 Nickel Belt France GŽlinas New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-9203 Oshawa Jennifer K. French New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0117 Parkdale-High Park Cheri DiNovo New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0244 Timiskaming-Cochrane John Vanthof New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2000 Timmins-James Bay Gilles Bisson -

Hon. David Orazietti Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services 16 Floor, George Drew Building 25 Grosvenor Street T

Hon. David Orazietti Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services 16th Floor, George Drew Building 25 Grosvenor Street Toronto, ON M7A 1Y6 July 25, 2016 RE: End the Incarceration of Immigration Detainees in Provincial Prisons Dear David, First, let me extend on behalf of Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario (RNAO), a warm welcome and congratulations on your recent appointment as the Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services. We at RNAO look very much forward to working with you to build healthier communities in our province. To this end, we are asking to meet with you to discuss perspectives and collaboration. As the professional association representing registered nurses (RN), nurse practitioners (NP) and nursing students in Ontario, RNAO is a strong and consistent advocate for the need to improve health, health care, and human rights protection within our provincial correctional facilities.1 2 We have long been concerned with the criminalization of people with mental health and addiction challenges.3 Therefore, we urge you to end the ongoing incarceration of immigration detainees in provincial prisons, and prevent more needless deaths of immigration detainees in your care. The Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) routinely transfers immigration detainees – refugee claimants, survivors of trauma, and other vulnerable non-citizens, including many with mental health challenges – to medium-maximum security provincial correctional facilities.4 Having a severe physical or mental illness or expressing thoughts -

Political Parties

LESSON 4: Political Parties OBJECTIVE QUESTIONS TO EXPLORE DURING THIS LESSON • What is a political party? What purpose do they serve? Students will • How do political parties form government? learn about • Which political parties can you name? political • What is a party platform? • What is each party’s platform or what promises are they making if they get elected? perspectives and political parties, SUPPLEMENTARY TOOLS • PowerPoint 4: Political Parties and research • Handout 4.1: 2011 Election Results the parties • Worksheet 4.2: Getting to Know the Parties • Worksheet 4.3: Where do you stand? campaigning • Worksheet 4.4: Vote for My Party in the federal • Worksheet 4.5: Watching the Leaders’ Debate election. TEACHING STRATEGIES Hook: 20-30 min KEY WORDS 1. Tell students to imagine that their school has been given a grant or sum of money to improve or expand the schoolyard. Lead a class brainstorming session on the political party, different ways in which the money could be spent. Record ideas on a blackboard, political ideology, chart paper or Smartboard. perspective, 2. Group similar ideas together so that there are four to six main ideas. Help political party, students form groups (‘parties’) based on their interests. Ask each group to discuss their ideas in more detail and record reasons why their ideas are good ones. Ask party leader, each group to put together a one-minute pitch. candidate, slogan, party platform, 3. Give each group one minute to share their pitch with the rest of the class. plank, riding Instruction: 10 min 1. When a community or large number of people need to get something done, people with similar interests often form groups and work together to achieve their goals. -

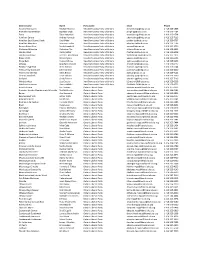

Public Accounts of the Province of Ontario for the Year Ended March

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS, 1994-95 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Hon. Elmer Buchanan, Minister DETAILS OF EXPENDITURE Voted Salaries and Wages ($87,902,805) Temporary Help Services ($1,329,292): Management Board Secretariat, 1,220,010; Accounts under $50,000—109,282. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries ($196,635): Environment and Energy, 196,635. Employee Benefits ($13,866,524) Payments for Canada Pension Plan, 1 ,594,486; Dental Plan, 95 1 ,332; Employer Health Tax, 1 ,702,083; Group Life Insurance, 170,970; Long Term Income Protection, 1,028,176; Supplementary Health and Hospital Plan, 1,016,690; Unemployment Insurance, 3,017,224; Unfunded Liability— Public Service Pension Fund, 1,024,574. Other Benefits: Attendance Gratuities, 401,716; Death Benefits, 18,660; Early Retirement Incentive, 467,244; Maternity/Parental/Adoption Leave Allowances, 530,045; Severance Pay, 1,494,057; Miscellaneous Benefits, 51,035. Workers' Compensation Board, 315,097. Payments to Other Ministries ($152,141): Accounts under $50,000—152,141. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries ($69,006): Accounts under $50,000—69,006. Travelling Expenses ($3,859,979) Hon. Elmer Buchanan, 7,002; P. Klopp, 3,765; R. Burak, 9,912; W.R. Allen, 13,155; D.K. Alles, 16,276; P.M. Angus, 23,969; D. Beattie, 12,681; A. Bierworth, 14,510; J.L. Cushing, 12,125; L.L. Davies, 11,521; P. Dick, 16,999; E.J. Dickson, 11,231; R.C. Donais, 10,703; J.R. Drynan, 10,277; R. Dunlop, 10,662; JJ. Gardner, 43,319; C.L. Goubau, 12,096; N. Harris, 12,593; F.R Hayward, 26,910; M. -

The People of Scarborough

~THE SCARf>OROUGH PuBLIC LIBF{\RY I BOARP THE PEOPLE OF SCARBOROUGH Map of Scarborough ,.; .; .,; ::. .,; .,; .,; "'""- :;, -< "" -< "" "" 'ti "" "" S.teele~ Ave. V IV Finch Avenue III Sileppail.d Ave. 11 D St. REFERENCE POINTS 1. Thomson Park Z. Bluffer's Park J 3. civic Centre 4. Kennedy Subway 5. Metro Zoo Ikml 6. Guild Inn 1 mile! Map of Scarborough courtesy of Rick Schofield, Heritage Scarborough THE PEOPLE OF SCARBOROUGH The City of Scarborough Public Library Board Copyright© The City of Scarborough Public Library Board 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise for purposes of resale. Published by The City of Scarborough Public Library Board Grenville Printing 25 Scarsdale Rd. Don Mills, Ontario M3B 2R2 Raku ceramic Bicentennial Collector Plate and cover photo by Tom McMaken, 1996. Courtesy of The City of Scarborough. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Myrvold, Barbara The People of Scarborough: a history Includes index. ISBN 0-9683086-0-0 1. Scarborough (Ont.) - History. I. Fahey, Curtis, 1951- . II Scarborough Public Library Board. III. Title. FC3099.S33M97 1997 971.3'541 C97-932612-5 F1059.5.T686S35 1997 iv Greetings from the Mayor As Mayor of the City of Scarborough, and on behalf of Members of Council, I am pleased that The People of Scarborough: A History, has been produced. This book provides a chronological overview of the many diverse peoples and cultures that have contributed to the city's economic, cultural and social fabric. -

Ontario Gazette Volume 140 Issue 43, La Gazette De L'ontario Volume 140

Vol. 140-43 Toronto ISSN 0030-2937 Saturday, 27 October 2007 Le samedi 27 octobre 2007 Proclamation ELIZABETH THE SECOND, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom, ELIZABETH DEUX, par la grâce de Dieu, Reine du Royaume-Uni, du Canada and Her other Realms and Territories, Queen, Head of the Canada et de ses autres royaumes et territoires, Chef du Commonwealth, Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. Défenseur de la Foi. Family Day, the third Monday of February of every year, is declared a Le jour de la Famille, troisième lundi du mois de février de chaque année, holiday, pursuant to the Retail Business Holidays Act, R.S.O. 1990, est déclaré jour férié conformément à la Loi sur les jours fériés dans le Chapter R.30 and of the Legislation Act, 2006, S.O. 2006 c. 21 Sched. F. commerce de détail, L.R.O. 1990, chap. R.30, et à la Loi de 2006 sur la législation, L.O. 2006, chap. 21, ann. F. WITNESS: TÉMOIN: THE HONOURABLE L’HONORABLE DAVID C. ONLEY DAVID C. ONLEY LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR OF OUR LIEUTENANT-GOUVERNEUR DE NOTRE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO PROVINCE DE L’ONTARIO GIVEN at Toronto, Ontario, on October 12, 2007. FAIT à Toronto (Ontario) le 12 octobre 2007. BY COMMAND PAR ORDRE DAVID CAPLAN DAVID CAPLAN Minister of Government Services (140-G576) ministre des Services gouvernementaux Parliamentary Notice Avis parlementaire RETURN OF MEMBER ÉLECTIONS DES DÉPUTÉS Notice is Hereby Given of the receipt of the return of members on Nous accusons réception par la présente des résultats du scrutin, or after the twenty-sixth day of October, 2007, to represent -

(& Windows) Opens Doors

A Magazine for Alumni and Friends of Mohawk College Mohawk Diploma Fall 2004 OPENSOPENS DOORSDOORS (&(& WINDOWS)WINDOWS) Peter Rakoczy, Mohawk Alumnus and GM of Worldwide Microsoft Consulting Services Strategy shares some ‘Words of Wisdom’ Publications Mail Agreement 40065780 ALSO INSIDE: Movin’ On Up ~ Turn Up the Heat ~ Life of the Party FEATURES O N T H E COVER 24 WORDS TO LIVE BY Peter Rakoczy’s Mohawk diploma helped him open doors to become one of the top players in Microsoft’s global empire. In this exclusive interview with In Touch he shares some words of wisdom about the secrets of his success. BY KATE SCHOOLEY LIFE OF THE PARTY 16 Mohawk grad Doug Dreher’s career has blown-up big time. DEPARTMENTS As General Manager of the Pioneer Baloon Company the Welcoming Words. 4 decision to go to Mohawk inflated his career opportunities Alumni News. 6 and left him flying high. BY K. L. SCHMIDT Upcoming Events . 8 Alumni Varsity . 9 STRATEGY FOR SUCCESS Around Campus . 10 Fundraising Update . 14 22 Mohawk President MaryLynn West-Moynes shares her Strategic Plan for keeping Mohawk College at the forefront Keeping In Touch . 36 of education in Ontario. BY KATE SCHOOLEY Looking Back . 38 MOVIN’ ON UP 28 Recent renovations to the Mohawk Student Association ALSO INSIDE aims to increase visibilty of the services the MSA offers MOHAWK IN MEMORIAM 35 to students. BY LYNN JAMES A Fighter, A Friend Mohawk College remembers TURN UP THE HEAT the many contributions that 32 Meet Mohawk Alumnus Chris Dennis, who used his Mohawk Alumnus, and local Mohawk Diploma to help build his family’s business into politician Dominic Agostino a leading-edge supplier of heat-treat services.