Chandrasiri Gen. Cyril Ranatunga and Others

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

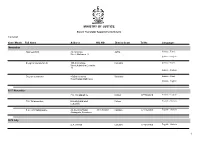

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Nirekha De Silva Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Copyright© WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama, New Delhi, India, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama Core 4A, UGF, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110 003, India This initiative was made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation. The views expressed are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of WISCOMP or the Foundation for Universal Responsibility of HH The Dalai Lama, nor are they endorsed by them. 2 Contents Acknowledgements 5 Preface 7 Introduction 9 Methodology 11 List of Abbreviations 13 Civil War in Sri Lanka 14 Army Women 20 LTTE Women 34 Peace and the process of Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration 45 Human Needs and Human Rights in Reintegration 55 Psychological Barriers in Reintegration 68 Social Adjustment to Civil Life 81 Available Mechanisms 87 Recommendations 96 Directory of Available Resources 100 • Counselling Centres 100 • Foreign Recruitment 102 • Local Recruitment 132 • Vocational Training 133 • Financial Resources 160 • Non-Government Organizations (NGO’s) 163 Bibliography 199 List of People Interviewed 204 3 4 Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr. Meenakshi Gopinath and Sumona DasGupta of Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace (WISCOMP), India, for offering the Scholar for Peace Fellowship in 2005. -

THE CEYLON GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No

THE CEYLON GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No. 10,462 —FRIDAY, OCTOBER 10, 1052 Published by Authority PART VI-LIST OF JURORS AND ASSESSORS (Separate paying is given to each P ait m order that it mat/ be filed separately) MIDLAND CIRCUIT 26 Amaradasa, Balage Wilson, Teamaker, Atta- bagie Group, Gampola CENTRAL PROVINCE— Kandy District 27 Ambalavanar, P., Head Clerk, National Bank of India Ltd , Kandy LIST of persons in the Central Province, residing 28 Am banpola, D. G , Clerk, D R. C., P. W. D., within a line of 30 miles radius from Kandy or 3 miles K a rd y of a Railway Station, who are qualified to serve as 29 Amerasekera, Karunagala Pathiranage Jurors and Assessors at Kandy, under the provision of Suwaris, Teacher, Dharmara.ia College, the Criminal Procedure Code for the year July, 1952, K andy to June, 1953. • 11 30 Amerasekera, Verahennidege Ariya, Man N B.— The Jurors numbered m a separate senes, on ager, Phoenix Studio, Ward Street, the left of those indicating Ordinary Jurors, are qualified K andy to serve as Special Jurors. 12 31 Amerasekera, Alexander Merrill, Superin tendent, Coolbawa, Nawalapitiya 13 32 Amerasekera, Eric Mervyn, Proprietory ENGLISH-SPEAKING JURORS Planter, Rest Harrow, Wattegama I Abdeen, M L. J., Landed Proprietor, 39, 33 Amerasinghe, Arthur Michael Perera, Illawatura, Gampola Superintendent, Pilessa, Mawatagama 1 2 Abdeen, O. Z., Landed Proprietor, • 68/5, 14 34 Amerasinghe, R. M., Teacher, St. Sylvesters Illawatura, Gampola College, Kandy 3 Abdeen, E. S. Z., Head Clerk, 218, Kandy 15 35 Amukotuwa, Nandasoma, Proprietory Road, Gampola Planter, Herondale Estate, Nawalapitiya 2. -

Documents Refer to Any Special Cadre Based on Gender Or Otherwise for the Promotion to the Rank of ASP

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In a matter of an application in terms of Article 17 and 126 of the Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. 1. Chief Inspector W.A.J.H. Fonseka 125/41, Pannipitiya Road, Baththaramulla. 2. Chief Inspector W.K.J.R. Dias No. 126, Piyadasa Sirisena Mawatha, Colombo 10. 3. Chief Inspector R.A.R.N. Rajapaksha SC (FR) Application No. 73/2009 No. 1/2, Police Flats, Colombo 10. 4. Chief Inspector Prasad Siriwardana [now deceased] No. 230, Goonawella, Kelaniya. PETITIONERS -Vs- 1. Neville Piyadigama, Chairman, National Police Commission, 3rd Floor, Rotunda Building, No. 109, Galle Road, Colombo 3. 1(a) Senaka Walgampaya, P.C. – Chairman, NPC 1(a)(i) Prof. Siri Hettige – Chairman, NPC 1(a)(ii) Tilak Kollure – Chairman, NPC 1(a)(iii) P.H. Manatunga – Chairman, NPC 1(a)(iv) K.W.E. Karaliyadde – Chairman, NPC 1(A) Vidyajothi Dr. Dayasiri Fernando – Chairman 1(A)(i) Jus. Sathya Hettige, P.C. – Chairman 1(A)(ii) Dharmasena Dissanayake – Chairman 1(B) Palitha M. Kumarasinghe, P.C. – Member 1 1(B)(i) Kanthi Wijetunga – Member 1(B)(ii) A. Salam Abdul Waid – Member 1(B)(iii) Prof. Hussain Ismail – Member 1(B)(iv) Mrs. Sudharma Karunaratne – Member 1(C) Sirimavo A. Wijeratne – Member 1(C)(i) Sunil S. Sirisena – Member 1(C)(ii) Ms. D.S. Wijeythilake – Member 1(C)(iii) G.S.A. De Silva, P.C. – Member 1(D) S.C. Mannampperuma – Member 1(D)(i) Dr. Pradeep Ramanujam – Member 1(E) Ananda Seneviratne – Member 1(E)(i) Mr. -

DISAPPEARANCES Disappeared

This study explores the impact of the ruling elite’s political project through the experiences of 87 relatives of the DISAPPEARANCES DISAPPEARANCES disappeared. It considers how their own A SOCIOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF A SOCIOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF political project to re-establish the IN SRI LANKA socio–legal identity of the disappeared was exploited by the political elite and their own communities rendering them socially ostracised. Within this context, DISAPPEARANCES transitional justice mechanisms including prosecutions and social movements were manipulated and IN SRI LANKA politicised along party lines as part of a ritual of conspiracy against the victims to deny state terror and protect those responsible for it. About the author: Jane Thomson-Senanayake, B.A Hons (NSW), Grad Dip (NSW), Grad Cert (New England), M.A (Deakin), PhD (Sydney), is a human rights and social policy researcher. Her academic J research has focused on political ane Thomson-Senanayake violence, enforced disappearances, transitional justice and social restoration in contexts including Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia and East Timor. She was awarded the Lionel Murphy Postgraduate Scholarship in 2004 and completed her PhD in 2013 at the University of Sydney. Her doctoral research, which explored enforced disapearances over three decades in Sri Lanka and involved extensive fieldwork across eight districts, provided the basis Rs 1000/= Jane Thomson-Senanayake for this publication. Asian Human Rights Commission, Unit 1 & 2 12/F, Hopeful Factory Centre 10-16 Wo Shing Street, Fotan, N.T. ,Hong Kong, China A SOCIOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF DISAPPEARANCES IN SRI LANKA ''Not even a person, not even a word...'' Jane Thomson-Senanayake ii A sociological exploration of disappearances in Sri Lanka ''Not even a person, not even a word...'' © Jane Thomson-Senanayake 2014 ISBN (Print) : 978-955-4597-04-4 Published by Asian Human Rights Commission Unit 1 & 2 12/F. -

Peace Confidence Index 21 – Topline Results

Peace Confidence Index Top-Line Results CONTENTS • INTRODUCTION 01 • KEY NATIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 02 • FINDINGS AT A GLANCE 08 • PEACE CONFIDENCE INDEX (PCI) 13 TOP-LINE RESULTS IMPORTANT ISSUES 13 SOLUTIONS 14 CONFIDENCE 18 CEASEFIRE AGREEMENT (CFA) 22 SRI LANKA MONITORING MISSION (SLMM) 27 FOREIGN INVOLVEMENT 31 • POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS 37 • ANNEX Copyright © Social Indicator February 2006 Peace Confidence Index Page 1 Top-line Results INTRODUCTION OBJECTIVE The purpose of this study is two-fold. One is to develop a numerical indicator of the level of public confidence in the peace process using a set of standardized questions, which remain unchanged with each wave. The other is to use a set of questions related to recent social, economic and political developments in order to gauge public opinion on the peace process, which by definition will change from one wave to another. Such information, collected over a period of time, will provide civil society and policy makers a useful barometer of Sri Lankan polity’s opinions, and ensure that such collective opinions are given due importance and incorporated into the policy debate. SCOPE & METHODOLOGY The survey is carried out using a structured questionnaire administered through face-to-face interviews amongst a 1362 randomly selected sample. This survey was conducted in 17 administrative districts, excluding the North and East due to the violence prevalent in the months prior. Data is weighted to reflect the actual ethnographic composition of the districts in which the sample was surveyed. This is the twenty first wave of the PCI study, which was first conducted in May 2001.This publication presents only the top-line results of the February 2006 survey. -

In the Supreme Court of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application under Article 126 of the Constitution of Sri Lanka. 1. W, K. B. Seneviratne, 376/A2, Shanthi Mawatha, Kirillawala. And 5 Others PETITIONERS S.C. (F.R.) APPLICATION NO. 105/08 VS. 1. Justice P. R. P. Perera, Chairman, Public Service Commission, No. 46, Vauxhall Street, Colombo 02. And 23 Others RESPONDENTS BEFORE : Saleem Marsoof, P.C., J., P. A. Ratnayake, P. C., J., & Chandra Ekanayake, J. COUNSEL : J. C. Weliamuna with N. S. Ranaweera for Petitioners M. K. B. A. Jayasinghe, D.S.G., for 1st-4th, 6th-10th, 11th, 12th-14th and 24th Respondents. ARGUED ON : 25-11-2009 DECIDED ON : 1.04.2010 MARSOOF, J. The Petitioners are Class II-Jailors of the Department of Prisons, falling within the purview of the Ministry of Justice and Law Reforms, and have in this application under Article 17 read with Article 126 of the Constitution, sought to challenge the promotions of the 16th to 23rd Respondents to the post of Class I-Jailor in the said Department and the failure to promote the Petitioners to the said post. The Petitioners, who are all 1 senior jailors in Class II of the service, claim that their fundamental right to equality enshrined in Article 12(1) of the Constitution has been violated by the actions of the 1st to 15th Respondents or any one or more of them, which have resulted in the 16th to 23rd Respondents who are more junior in the service being promoted over the Petitioners, who even otherwise are more qualified than the said Respondents. -

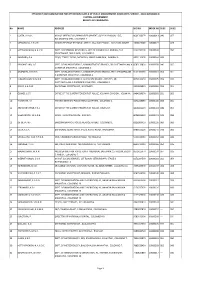

EB PMAS Class 2 2011 2.Pdf

EFFICIENCY BAR EXAMINATION FOR OFFICERS IN CLASS II OF PUBLIC MANAGEMENT ASSISTANT'S SERVICE - 2011(II)2013(2014) CENTRAL GOVERNMENT RESULTS OF CANDIDATES No NAME ADDRESS NIC NO INDEX NO SUB1 SUB2 1 COSTA, K.A.G.C. M/Y OF DEFENCE & URBAN DEVELOPMENT, SUPPLY DIVISION, 15/5, 860170337V 10000013 040 057 BALADAKSHA MW, COLOMBO 3. 2 MEDAGODA, G.R.U.K. INLAND REVENUE REGIONAL OFFICE, 334, GALLE ROAD, KALUTARA SOUTH. 745802338V 10000027 --- 024 3 HETTIARACHCHI, H.A.S.W. DEPT. OF EXTERNAL RESOURCES, M/Y OF FINANCE & PLANNING, THE 823273010V 10000030 --- 050 SECRETARIAT, 3RD FLOOR, COLOMBO 1. 4 BANDARA, P.A. 230/4, TEMPLE ROAD, BATAPOLA, MADELGAMUWA, GAMPAHA. 682113260V 10000044 ABS --- 5 PRASANTHIKA, L.G. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATIVE BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM A 858513383V 10000058 040 055 GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 6 ATAPATTU, D.M.D.S. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATION BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM 816130069V 10000061 054 051 A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 7 KUMARIHAMI, W.M.S.N. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ACCOUNTS BRANCH, POB 515, SRI 867010025V 10000075 059 070 CHITTAMPALAM A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 8 JENAT, A.A.D.M. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, NEGOMBO. 685060892V 10000089 034 051 9 GOMES, J.S.T. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA DIVISION, KELANIYA. 846453857V 10000092 031 052 10 HARSHANI, A.I. FINANCE BRANCH, POLICE HEAD QUARTERS, COLOMBO 1. 827122858V 10000104 064 061 11 ABHAYARATHNE, Y.P.J. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA. 841800117V 10000118 049 057 12 WEERAKOON, W.A.D.B. 140/B, THANAYAM PLACE, INGIRIYA. 802893329V 10000121 049 068 13 DE SILVA, W.I. -

List of Printing Presses in Sri Lanka

LIST OF PRINTING PRESSES IN SRI LANKA (CORRECTED UPTO DECEMBER 31st 2013) DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL ARCHIVES NO. 07, PHILIP GUNAWARDENA MAWATHA, COLOMBO 07, SRI LANKA. 1 AMPARA DISTRICT Name of the Press Postal Address Proprietor Ampara Jayasiri Press. 59, Kalmunai Road, Ampara. P. S. A. Dharmasena Piyaranga Press, 46, D. S. Senanayaka Veediya, W. Albert Ampara. Samaru Printrs, 41/A, Fourth Avenue, D. B. Ariyawathi Ampara. A. T. Karunadasa S. A. Piyasena N. D. C. Gunasekara K. D. Chandralatha D. W. Dayananda I. G. Piyadasa E. D.Wicramasinghe G. G. Jayasinghe G. G. Siripala Akkaraipattu Expert Printers, 5, Careem Road, J. Mohamed Ashraf Akkaraipattu-01 Ruby printers, Main Street, Akkaraipattu F. M. Vussuflebai Kalmunai An – Noor Graphics Offset Akkarapattu Road, Kalmunai. Lebbe Khaleel Printers, Rahman Azeez Printing Industries, 97, Main Street, Kalmunai A. A. Azeez Godwin Press, 147, Main Street, Kalmunai T. Mahadeva Illampirai Press, Division, No. 1, Main Street M. I. M. Salih Marudamunai, Kalmunai Manamagal Auto Main Street, Kalmunai M. A. A. Majeed Printing Industries, Modern Printers, 139, Main Street, Kalmunai P. V. Kandiah 2 Maruthamunai Abna Offset Printers. 07, Main Street, U. L. Muhamed Maruthamunai.-01 Nakip Sainthamurathu National Printers, Main Street, Sainthamurathu Z. Z. K. Kariapper Royal Offset Printers, 254 A, Main Street, Abdul Haq Jauffer Sainthamaruthu - 09 Kariapper Star Offset Printers, 502, Main Street, M. I. H. Ismail Sainthamurathu Samanthurei. Easy Prints, Hidra Junction, Samanthurei. Ibra Lebbai Rizlia Sandunpura Eastern Press, 172, Muruthagaspitiya, G. G. Karunadasa Sandunpura Uhana Tharindu Offset Printers. Uhana. Meththananda Rubasinghe 3 ANURADHAPURA DISTRICT Name of the Press Postal Address Proprietor Anuradhapura Charles Press, 95 , Maitripala Senanayake- T. -

Sri Lanka-Homicide of Richard De Zoysa-Fact Finding Mission Report

INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF JURISTS P.O. Box 120, 1224 Chene-Bougeries/Geneva, Switzerland Telex: 418 531 ICJ CH Telephone: (4122} 49 35 45 Fax: (4122} 49 31 45 Report of Anthony Heaton-Armstrong, Observer appointed by the International Commission of Jurists August 1990 CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND . 1 2. SUMMARY OF OBSERVER'S INVOLVEMENT........... 3 3. PERSONAE . 5 4. CHRONOLOGY . 7 5. OBSERVATIONS . 15 ; 6. EVIDENCE OF INDENTIFICATION IMPLICATING SSP GUNASINGHE AND COMMENTARY................ 18 7. COMMENTARY AND CONCLUSIONS .................. 20 7.1 THE POLICE INVESTIGATIONS .................... 20 7.2 THE ROLE OF THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL............. 21 7 . 3 THE ROLE OF THE COURT . 2 3 7 . 4 THE FUTURE . 2 3 8. LIST OF ADDENDED DOCUMENTS 26 L15t2.A{2.y International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) Geneva, Switzerland /v\ 1\() MAGISTERIAL INQUIRY INTO THE HOMICIDE OF RICHARD DE ZOYSA Report of the observer appointed by the International Commission of Jurists 1. BACKGROUND On 18 February 1990 Richard de Zoysa, a 31 year old journalist, was abducted from his home near Colombo in Sri Lanka in the early hours of the morning by a group of men. His body was found in the sea on 19 February. He had been shot. A magisterial inquiry into the killing was instituted shortly afterwards. About three-and-a-half months later Mr de Zoysa's mother, Dr Manorani Saravanamuttu, who had been present at the abduction, claimed to have identified one of the abductors as Senior Superintendent of Police Ronnie Gunasinghe when watching a television news broadcast on which he had appeared. The police authorities declined to arrest Mr Gunasinghe. -

Civil-Military Relations in Post-Conflict Sri Lanka: Successful Civilian Consolidation in the Face of Political Competition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2015-12 Civil-military relations in post-conflict Sri Lanka: successful civilian consolidation in the face of political competition Wijayaratne, Chaminda Athapattu Mudalige P. Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/47897 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN POST-CONFLICT SRI LANKA: SUCCESSFUL CIVILIAN CONSOLIDATION IN THE FACE OF POLITICAL COMPETITION by Chaminda Athapattu Mudalige P. Wijayaratne December 2015 Thesis Advisor: Anshu Nagpal Chatterjee Second Reader: Florina Cristiana Matei Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED (Leave blank) December 2015 Master’s thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN POST-CONFLICT SRI LANKA: SUCCESSFUL CIVILIAN CONSOLIDATION IN THE FACE OF POLITICAL COMPETITION 6.