I Did My Time: the Transformation of Indiana's Expungement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

1 Paroled Anthony Ehlers Northwestern University, RTVF Scene

1 Paroled Anthony Ehlers Northwestern University, RTVF Scene: A man in a prison cell. He has a bunk, a toilet and sink, a desk and a stool. On the stool is a coffee cup, and scattered papers. There should be indications of bars on either side of his cell, to indicate the presence of other cells. Occasionally he will talk to one of his neighbors, a voice offstage can answer. Two people will walk by his cell and speak with him. Otherwise it is essentially a solo performance. The lighting should be somewhat dim, especially on either side of him, only his cell is lit. A woman walks to his bars with a clipboard. WOMAN Are you Anthony Moon B216173? MOON Yeah, what’s up? WOMAN The state of Illinois has decided that you have paid your debt to society. You’re being paroled. I need you to fill this form out iMMediately. We need an address for you to parole to. 2 M (MOON) Wait, what? WOMAN You’re being paroled. M When? No one said anything to me! WOMAN I’m saying something to you now. M Who did this? Why didn’t I know anything about it? WOMAN I don’t know, that’s above my pay grade. What I need for you to do is fill out that form and have it ready for me when I come back. She begins to walk away M Wait! Miss, hold on! 3 WOMAN What?! M I didn’t ask to be paroled, how can they do this? WOMAN I told you, I don’t know. -

Roxbox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat

RoxBox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat. Thomas Jules & Bartender Jucxi D Blackout Careless Whisper Other Side 2 Unlimited 10 Years No Limit Actions & Motives 20 Fingers Beautiful Short Dick Man Drug Of Choice 21 Demands Fix Me Give Me A Minute Fix Me (Acoustic) 2Pac Shoot It Out Changes Through The Iris Dear Mama Wasteland How Do You Want It 10,000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Because The Night 2Pac Feat Dr. Dre Candy Everybody Wants California Love Like The Weather 2Pac Feat. Dr Dre More Than This California Love These Are The Days 2Pac Feat. Elton John Trouble Me Ghetto Gospel 101 Dalmations 2Pac Feat. Eminem Cruella De Vil One Day At A Time 10cc 2Pac Feat. Notorious B.I.G. Dreadlock Holiday Runnin' Good Morning Judge 3 Doors Down I'm Not In Love Away From The Sun The Things We Do For Love Be Like That Things We Do For Love Behind Those Eyes 112 Citizen Soldier Dance With Me Duck & Run Peaches & Cream Every Time You Go Right Here For You Here By Me U Already Know Here Without You 112 Feat. Ludacris It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Hot & Wet Kryptonite 112 Feat. Super Cat Landing In London Na Na Na Let Me Be Myself 12 Gauge Let Me Go Dunkie Butt Live For Today 12 Stones Loser Arms Of A Stranger Road I'm On Far Away When I'm Gone Shadows When You're Young We Are One 3 Of A Kind 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

2019 Delta Winds

A Collection of Student Essays Volume 32 DELTA2019 WINDSDelta Winds, Vol. 32 | 1 LETTER FROM THE EDITORS In the fall of 1991, the first volume of Delta Winds appeared for sale for $2.00 in the bookstore of San Joaquin Delta College. Newly-hired English faculty member Jane Dominik created the magazine with the intent of publishing student essays that “merit a wider reading audience.” Five years later, while standing in line for the commencement ceremonies, she asked Robert Bini and William Agopsowic to take over the reins of her project, which by then had become well- received in the English Department. They agreed under the condition that her biannual publication become an annual publication. They knew they could never keep up with Jane’s pace, but they figured that two of them could do half the work that she did. And even so, it would be a challenge. Over a year period, Bob and Will continued to identify student essays deserving of a wider reading audience. Thanks to a sabbatical leave in 2000, they were able to create an online version of Delta Winds to complement the print version. In doing so, they expanded the audience from those obtaining the locally distributed 800 print copies to an unlimited number of readers on the Internet. With that came easier distribution, and in time publishing houses were regularly knocking on their door, requesting to reprint Delta Winds essays in their textbooks. It has been a real privilege to carry on the rich tradition that Jane, Bob, and Will have passed on to us. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

Korn Highlights a Comprehensive List of Accomplishments While Brian "Head" Welch Was a Member of Korn

Korn Highlights A comprehensive list of accomplishments while Brian "Head" Welch was a member of Korn AWARDS Won a Grammy for Best Metal Performance – 2003 Won a Grammy for Short Form Music Video – 2000 Won a MTV Video Music Award for Best Rock Video – 2000 Won a MTV Video Music Award for Best Editing – 1999 Won a MTV Video Music Award for Best Heavy Metal / Hard Rock Video – 1999 NOMINATIONS Grammys Best Metal Performance – 2004 Hard Rock Performance – 2000 Best Metal Performance – 1997 MTV Video Music Awards Best Rock Video – 2002 Best Art Direction – 1999 Video of the Year – 1999 Best Direction – 1999 Best Special Effects – 1999 Best Cinematography – 1999 Best Breakthrough Video – 1999 Viewer’s Choice – 1999 MTV Europe Awards Best Live Act – 2002 SALES HISTORY 16 Million albums sold to date in the US 32 Million albums sold worldwide as of 2009 ALBUMS Life Is Peachy (1996) Sold more than 106,000 copies its first week Follow The Leader (1998) Sold 268,000 copies its first week Certified 5x Platinum by RIAA and sold 10 million copies worldwide Issues (1999) Sold 573,000 copies Certified 3x Platinum SALES HISTORY (continued) Untouchables (2002) Sold 434,000 copies Certified Platinum Paradigm Shift (2013) Sold 113,000 DISCOGRAPHY Korn (1995) #1 on Heatseekers #72 on The Billboard 200 Life Is Peachy (1996) #3 on The Billboard 200 Follow the Leader (1998) #1 on The Billboard 200 #1 on Top Canadian Albums Issues (1999) #1 on The Billboard 200 #2 on Top Canadian Albums #2 on Top Internet Albums Untouchables (2002) #2 on The Billboard 200 #2 on Top Internet Albums #3 on Top Canadian Albums Take a Look in the Mirror (2003) #9 on Top Internet Albums #9 on The Billboard 200 Greatest Hits Vol. -

Korn All Albums Download Korn – Discography (1994 – 2014) UPDATE

korn all albums download Korn – Discography (1994 – 2014) UPDATE. Korn – Discography (1994 – 2014) EAC Rip | 19xCD + 4xDVD | FLAC Image & Tracks + Cue + Log | Full Scans included Total Size: 11.2 GB | 3% RAR Recovery STUDIO ALBUMS | LIVE ALBUMS | COMPILATION | EP Label: Various | Genre: Alternative Rock, Nu Metal. Korn’s cathartic alternative metal sound positioned the group among the most popular and provocative to emerge during the post-grunge era. Korn began their existence as the Bakersfield, California-based metal band LAPD, which included guitarists James “Munky” Shaffer and Brian “Head” Welch, bassist Reginald “Fieldy Snuts” Arvizu, and drummer David Silveria. After issuing an LP in 1993, the members of LAPD crossed paths with Jonathan Davis, a mortuary science student moonlighting as the lead vocalist for the local group Sexart. They soon asked Davis to join the band, and upon his arrival the quintet rechristened itself Korn. After signing to Epic’s Immortal imprint, they issued their debut album in late 1994; thanks to a relentless tour schedule that included stints opening for Ozzy Osbourne, Megadeth, Marilyn Manson, and 311, the record slowly but steadily rose in the charts, eventually going gold. Its 1996 follow- up, Life Is Peachy, was a more immediate smash, reaching the number three spot on the pop album charts. The following summer, they headlined Lollapalooza, but were forced to drop off the tour when Shaffer was diagnosed with viral meningitis. While recording their best-selling 1998 LP Follow the Leader, Korn made national headlines when a student in Zeeland, Michigan, was suspended for wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the group’s logo (the school’s principal later declared their music “indecent, vulgar, and obscene,” prompting the band to issue a cease-and-desist order). -

Lyrics for Grandview Station Album in Order, Pages 2-10 Loser Bad Mood

Lyrics for Grandview Station album in order, pages 2-10 Loser Bad Mood Rising Where I’m Not Wanted Hate To Love You Crashing By Design Fall From Grace Unheeded Warnings (No Lyrics to Acid Reign) Between The Lines It Won’t Be Me Loser Ain’t no surprise you got nowhere to go Ain’t no surprise you got nothing to show Nobody’s worried over nothing for you Cause you only got one way to go You got nobody you can call on for help I guess that’s what you get for being yourself It’s not appealing and it just won’t sell The only thing you do is repel Chorus: You’re a loser and you know it And you can’t help but to show it You’re a loser gotta face it And I know it’s a drag but there’s no turning back Why do you always have to lie to yourself You ain’t no good at fooling nobody else Just give it up and take a look at yourself And tell me what you see in there Chorus If I hurt your feelings It makes it more appealing Just to know you hurt at all You do the scratching cause you planted the itch You never can seem to get out of the ditch I really hate it that you’ll never be rich But it is what it is what it is Chorus Bad Mood Rising Chorus: Gotta get up gotta get up gotta get going Gotta get up gotta get up gotta get gone Every time I think I’m out they pull me right back in Every time I think about it gets under my skin Chorus I can’t sit around and think about this for too long I might end up on the brink of doing something wrong Can’t get up, can’t stay down Nothing lost, nothing found Where I’m Not Wanted I don’t hang around where I’m not wanted -

Frank Filipetti - Discography Updated 09.14.14 P=Produce / E=Engineer / M=Mix/ L=Live

JDManagement.com 914.777.7677 Frank Filipetti - Discography updated 09.14.14 P=Produce / E=Engineer / M=Mix/ L=Live AWARD WINNERS & NOMINATIONS ARTIST / COMPOSER / PROGRAM FILM SCORE / ALBUM / TV SHOW CREDIT MOVIE STUDIO / RECORD LABEL / NETWORK Grammy - Best Musical Theater Album The Book of Mormon (2011) E/M Ghostlight Grammy - Best Musical Theater Album Monty Python's Spamalot (2005) E/M Decca Broadway Grammy - Best Musical Theater Album Wicked (2004) E/M Universal Music Group Grammy - Best Musical Theater Album Elton John & Tim Rice's Aida (2004) P/E/M Walt Disney Records Grammy - Best Pop Album Hourglass (1997) P/E/M Columbia Records James Taylor Grammy - Best Engineered Album (Non Classical) Hourglass (1997) E Columbia Records James Taylor ARTIST / COMPOSER / PROGRAM FILM SCORE / ALBUM / TV SHOW CREDIT MOVIE STUDIO / RECORD LABEL / NETWORK 2014 George Michael Symphonica E/M Universal Adriana Rozario Adriano Rozario P/E/M Independent Various Artists Aladdin (Original Broadway Cast Recording) P/E/M Universal Various Artists Bullets Over Broadway (Original Broadway Cast Recording) P/E/M Sony Masterworks Various Artists Frank Zappa's 200 Motels Live P/E/M Universal 2013 James Taylor The Essential James Taylor P Columbia Records/Sony Music Edie Brickell/Steve Martin Love Has Come For You E Rounder Korn Original Album Classics E Epic Laura Pausini "20 Grandes Exitos" E Warner Music Latina Various Artists Motown: The Musical (Original Broadway Cast Recording) P/M Universal Music 2012 Madonna MDNA E Interscope The Brecker Brothers The Complete -

Lean on Me - Bill Withers

LEAN ON ME - BILL WITHERS Sometimes in our lives, we all have pain, we all have sorrow but if we are wise, we know that there's, always tomorrow You just call on me brother, when you need a hand we all need somebody to lean on I just might have a problem, that you'll understand we all need somebody to lean on Lean on me, when you're not strong I'll be your friend, I'll help you carry on or it won't be long, 'til I'm gonna need somebody to lean on If there is a load, you have to bear, that you can't carry I'm right up the road, I'll share your load, if you just call me You just call on me brother, when you need a hand we all need somebody to lean on I just might have a problem, that you'll understand we all need somebody to lean on Lean on me, when you're not strong I'll be your friend, I'll help you carry on or it won't be long, 'til I'm gonna need somebody to lean on Lean on me, when you're not strong I'll give you strength, I'll help you carry on or it won't be long, 'til I'm gonna need somebody to lean on Lean on me, when you're not strong I'll give you strength, I'll help you carry on or it won't be long, 'til I'm gonna need somebody to lean on Call me, call me, call me You can lean on me BEAUTIFUL - CHRISTINA AGUILERA Ev'ry day is so wonderful and suddenly, it's hard to breathe Now and then, I get insecure from all the pain, I'm so ashamed I am beautiful no matter what they say words can't bring me down I am beautiful in every single way yes, words can't bring me down so don't you bring me down today To all your friends, you're delirious -

3 Doors Down

3 Doors Down - Here Without You 3 Doors Down - It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite (2) 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite 3 Doors Down - When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars - The Kill A Day To Remember - 2nd Sucks A Day To Remember - All I Want A Day To Remember - All Signs Point To Lauderdale A Day To Remember - Downfall Of Us All A Day To Remember - Have Faith In Me A Day To Remember - If It Means A Lot To You Ver2 A Day To Remember - If It Means A Lot To You A Day To Remember - Nj Legion Iced Tea A Day To Remember - The Downfall Of Us All Accept - Fast As A Shark ACDC - Shake Your Foundations ACDC - Back In Black ACDC - Big Gun ACDC - Highway To Hell ACDC - Shot Down In Flames ACDC - Stiff Upper Lip ACDC - T. N. T. Ace Frehley - New York Groove Aerosmith - Big Ten Inch Record Aerosmith - Cryin' Aerosmith - Don't Want To Miss A Thing Aerosmith - Dream On Aerosmith - Dude (2) Aerosmith - Dude Aerosmith - Hangman Jury Aerosmith - Hole In My Soul Aerosmith - I Don't Wanna Miss A Thing Aerosmith - I Don't Want To Miss A Thing Aerosmith - Jaded Aerosmith - Janie's Got A Gun Aerosmith - Just Push Play Aerosmith - Living On The Edge Aerosmith - Love In An Eleator Aerosmith - Rag Doll Aerosmith - Remember Aerosmith - Sweet Emotion Aerosmith - Toys In The Attic Aerosmith - What It Takes Aerosmith -Same Old Song And Dance Aerosmith- Back In The Saddle Alcatrazz - God Blessed Alestorm - Shipwrecked Alice Cooper - Is It My Body Alice Cooper - Last Man On Earth Alice Cooper - Lost In America Alice Cooper - No More Mr Nice Guy Alice Cooper - Poison Alice -

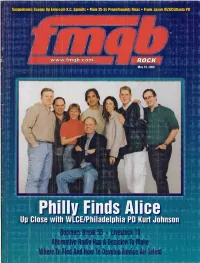

Up Close with IA111E/Philadelphia PD Kurt Johnson Boomers Break 55 • Lives Oc Alternative Radio Has a Decision to Make Whereth

Susquehanna Scoops Up Entercom K.C. Spinoffs •Male 25-34 Proportionality Rises •Frank Jaxon WZGC/Atlanta PD www.fmqb.com May 19, 2000 Up Close with IA111E/Philadelphia PD Kurt Johnson Boomers Break 55 •Lives oc Alternative Radio Has ADecision To Make WhereTh Find And How To Develop Novice Air Talent LUIS IfTHE Si INIL AGE "The Lost Art Of Keeping A Secret" On Your Desk Now! wvvvv.qotsa.com Impacting 5/22! wvvw.interscope.com D -,- C2000 lnterscope Records. All Rights Reser, ed. Publisher/Owner Rai Rudman Executive VP/GM Fred Deane c1qy 1) [email protected] www.tmob.com VP/Executive Director Paul Heine Ma 19 2000 •ISSUE No. 1193 [email protected] Managing Director/ Modern Rock Director Michael Parrish [email protected] upfront 3 Boomers Break 55 Administrative Director Currently there are around 58 million Americans 55 and older. But that number will swell Judy Swank to 66 million by 2004 and then keep growing for 14 years as the Baby Boom graduates to [email protected] the ranks of 55-plus. As the pig moves through the python, will it shift advertising dollars up the demographic ladder? And what are the implications for radio? Associate Director Jay Gleason 1 Doing Your Job Better: [email protected] Where To Find And How To Develop Novice Air Talent Attracting good part-time air talent is io longer as easy as relying on asteady stream of Progressive Director tapes and resumes from high school, college and broadcast school students. The key 17 Sybil McGuire rowadays is to change your way of thinking.