Kurt Weill Volume 29

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donald Mckayle Papers MS.P.023

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1k400389 No online items Guide to the Donald McKayle Papers MS.P.023 Finding aid prepared by Processed by Laura Clark Brown, machine-readable finding aid created by James Ryan, 1998; edited by Audra Eagle Yun, 2012. Special Collections and Archives, University of California, Irvine Libraries The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California, Irvine Irvine, California, 92623-9557 949-824-3947 [email protected] © 2012 Note Arts and Humanities --Performing Arts--DanceArts and Humanities--Performing Arts --Theater Guide to the Donald McKayle MS.P.023 1 Papers MS.P.023 Title: Donald McKayle papers Identifier/Call Number: MS.P.023 Contributing Institution: Special Collections and Archives, University of California, Irvine Libraries Language of Material: English Physical Description: 19.1 Linear feet(19 document boxes, 5 record cartons, 1 shoe box, 6 flat boxes, and 3 oversized folders) and 12.1 unprocessed linear feet Date (inclusive): 1930-2009 Abstract: Photographs, programs, production notes, music scores, audio and video recordings, costume designs, reviews, and other printed and graphic materials illustrate the eclectic career of world-renowned choreographer and University of California, Irvine Professor of Dance Donald McKayle. Early materials pertain to his youth in Harlem and his performance career in New York City in concert dance, theater and television. The bulk of the collection documents McKayle's career as the choreographer of over fifty concert dance pieces between 1948 and 1998 and as a director or choreographer for theatrical productions both off and on Broadway, including Raisin and Sophisticated Ladies. The materials illustrate the development of individual choreographic pieces, the evolution of McKayle as an artist, and his career as a dance educator. -

Broadway the BROAD Way”

MEDIA CONTACT: Fred Tracey Marketing/PR Director 760.643.5217 [email protected] Bets Malone Makes Cabaret Debut at ClubM at the Moonlight Amphitheatre on Jan. 13 with One-Woman Show “Broadway the BROAD Way” Download Art Here Vista, CA (January 4, 2018) – Moonlight Amphitheatre’s ClubM opens its 2018 series of cabaret concerts at its intimate indoor venue on Sat., Jan. 13 at 7:30 p.m. with Bets Malone: Broadway the BROAD Way. Making her cabaret debut, Malone will salute 14 of her favorite Broadway actresses who have been an influence on her during her musical theatre career. The audience will hear selections made famous by Fanny Brice, Carol Burnett, Betty Buckley, Carol Channing, Judy Holliday, Angela Lansbury, Patti LuPone, Mary Martin, Ethel Merman, Liza Minnelli, Bernadette Peters, Barbra Streisand, Elaine Stritch, and Nancy Walker. On making her cabaret debut: “The idea of putting together an original cabaret act where you’re standing on stage for ninety minutes straight has always sounded daunting to me,” Malone said. “I’ve had the idea for this particular cabaret format for a few years. I felt the time was right to challenge myself, and I couldn’t be more proud to debut this cabaret on the very stage that offered me my first musical theatre experience as a nine-year-old in the Moonlight’s very first musical Oliver! directed by Kathy Brombacher.” Malone can relate to the fact that the leading ladies she has chosen to celebrate are all attached to iconic comedic roles. “I learned at a very young age that getting laughs is golden,” she said. -

Donald Mckayle's Life in Dance

ey rn u In Jo Donald f McKayle’s i nite Life in Dance An exhibit in the Muriel Ansley Reynolds Gallery UC Irvine Main Library May - September 1998 Checklist prepared by Laura Clark Brown The UCI Libraries Irvine, California 1998 ey rn u In Jo Donald f i nite McKayle’s Life in Dance Donald McKayle, performer, teacher and choreographer. His dances em- body the deeply-felt passions of a true master. Rooted in the American experience, he has choreographed a body of work imbued with radiant optimism and poignancy. His appreciation of human wit and heroism in the face of pain and loss, and his faith in redemptive powers of love endow his dances with their originality and dramatic power. Donald McKayle has created a repertory of American dance that instructs the heart. -Inscription on Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival Award orld-renowned choreographer and UCI Professor of Dance Donald McKayle received the prestigious Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival WAward, “established to honor the great choreographers who have dedicated their lives and talent to the creation of our modern dance heritage,” in 1992. The “Sammy” was awarded to McKayle for a lifetime of performing, teaching and creating American modern dance, an “infinite journey” of both creativity and teaching. Infinite Journey is the title of a concert dance piece McKayle created in 1991 to honor the life of a former student; the title also befits McKayle’s own life. McKayle began his career in New York City, initially studying dance with the New Dance Group and later dancing professionally for noted choreographers such as Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, Sophie Maslow, and Anna Sokolow. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

BACKSTORY: the CREDITS an Actor

BACKSTORY Your behind-the-scenes look at TimeLine productions YESTERDAY’S STORIES. TODAY’S TOPICS. From Artistic Director PJ Powers a message Dear Friends, that their “Person of the — can influence history is made With his blend of social classic for the ages. You just Year” was You. Me. Us. The through activism, be On behalf of TimeLine’s not only in commentary and might be surprised that the average citizen. it personal, social or entire company, I am government emotional complexity, age in which it was written political. thrilled to welcome you to Admittedly, upon first buildings and Odets revolutionized the really is not our own! our 11th season! Each year hearing that, I thought There are many complex at corporate American theater during As we usher in a second we go through a series of it was a poor excuse for issues — not the least of board tables, but in the The Depression by putting decade of making history at discussions about the issues not choosing a person of which will be a Presidential homes and workplaces of the struggles and longings TimeLine, we’re delighted and types of stories we national prominence — a election — that will demand people like you and me. of everyday citizens on the to share another Odets stage. With Paradise Lost, want explore, and this year single someone who had great thoughtfulness in the We begin our season-long play with you. With much he gives voice to those our deliberations seemed made a sizeable imprint on coming year. Each of us will conversation by revisiting to discuss, I hope our little individuals and exposes a even more extensive and issues of global importance. -

2015 National Sports and Entertainment History Bee Round 1

2015 National Sports and Entertainment History Bee Round 1 1. In this film, one character is called “almost a guy you can’t hit” after the protagonist orders cranberry juice at a bar. In this film, a misspelling of the word “citizen” on an envelope causes one character’s identity to be revealed. One character in this remake of Infernal Affairs was loosely based on Whitey Bulger, that man was portrayed by Jack Nicholson. For the point, name this 2006 best picture winner directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Matt Damon and Leonardo DiCaprio. ANSWER: The Departed 2. This man was once part of a lopsided trade included relief pitchers Greg Caderay and Eric Plunk. He played for nine different teams between 1979 and 2003, including four stints with his original team, the Oakland Athletics. He holds Major League records for, unintentional walks, most runs scored, and leadoff home runs. For the point, name this outfielder who is best remembered for breaking Lou Brock’s record for the most career stolen bases, appropriately earning him the nickname "The Man of Steal". ANSWER: Rickey Henderson 3. One sequel to this book is entitled Small Steps, and follows Theodore Johnson. A song in this book goes “If only if only the woodpecker cries, the bark on the trees was as soft as the skies” and at one point, the protagonist takes refuge on “God’s thumb.” The protagonist is sent to Camp Green Lake after he is accused of stealing a pair of shoes, and his first name is his last name spelled backwards. -

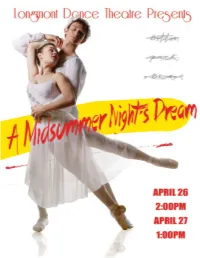

AMND-Program-Final.Pdf

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR KRISTIN KINGSLEY Story & Selected Lyrics from WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Music by FELIX MENDELSSOHN Ballet Mistress STEPHANIE TULEY Music Director/Conductor BRANDON MATTHEWS Production Design SEAN COCHRAN Technical Director ISAIAH BOOTHBY Lighting Design DAVID DENMAN Costume Design NAOMI PRENDERGAST, SUSIE FAHRING, ANN MARCECA, & WANDA RICE WITH STRACCI FOR DANCE NIWOT HIGH SCHOOL AUDITORIUM APRIL 26 2:00PM APRIL 27 1:00PM Longmont Dance Theatre Our mission is simply stated but it is not simple to achieve: we strive to enliven and elevate the human spirit by means of dance, specifically the perfect form of dance known as ballet. A technique of movement that was born in the courts of kings and queens, ballet has survived to this day to become one of the most elegant, most adaptable and most powerful means of human communication. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR BALLET MISTRESS Kristin Kingsley Stephanie Tuley LDT BOARD OF DIRECTORS RESIDENT OPERATION PERSONNEL President Susan Burton Production & Design Vice President Dolores Kingsley Lighting Designer/ David Denman Secretary Marcella Cox Production Stage Manager Members Sean Cochran, Jeanine Hedstrom, Eileen Hickey, Stage Manager Jenn Zavattaro David Kingsley, & Moriah Sullivan Technical Dir./Master Carpenter Isaiah Boothby Ballet Guild Liason Cathy McGovern Scenic Design & Fabrication Sean Cochran with Enigma Concepts and Designs Properties Coordinator Lisa Taft House Manager Marcella Cox RESIDENT COMPANY MANAGEMENT Auditorium Manager Jason Watkins (Niwot HS Auditorium) Willow McGinty Office -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Downtrodden Yet Determined: Exploring the History Of

DOWNTRODDEN YET DETERMINED: EXPLORING THE HISTORY OF BLACK MALES IN PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL AND HOW THE PLAYERS ASSOCIATION ADDRESSES THEIR WELFARE A Dissertation by JUSTIN RYAN GARNER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, John N. Singer Committee Members, Natasha Brison Paul J. Batista Tommy J. Curry Head of Department, Melinda Sheffield-Moore May 2019 Major Subject: Kinesiology Copyright 2019 Justin R. Garner ABSTRACT Professional athletes are paid for their labor and it is often believed they have a weaker argument of exploitation. However, labor disputes in professional sports suggest athletes do not always receive fair compensation for their contributions to league and team success. Any professional athlete, regardless of their race, may claim to endure unjust wages relative to their fellow athlete peers, yet Black professional athletes’ history of exploitation inspires greater concerns. The purpose of this study was twofold: 1) to explore and trace the historical development of basketball in the United States (US) and the critical role Black males played in its growth and commercial development, and 2) to illuminate the perspectives and experiences of Black male professional basketball players concerning the role the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA), collectively considered as the Players Association for this study, played in their welfare and addressing issues of exploitation. While drawing from the conceptual framework of anti-colonial thought, an exploratory case study was employed in which in-depth interviews were conducted with a list of Black male professional basketball players who are members of the Players Association. -

Kurt Weill Newsletter Protagonist •T• Zar •T• Santa

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume 11, Number 1 Spring 1993 IN THI S ISSUE I ssues IN THE GERMAN R ECEPTION OF W EILL 7 Stephen Hinton S PECIAL FEATURE: PROTAGON IST AND Z AR AT SANTA F E 10 Director's Notes by Jonathan Eaton Costume Designs by Robert Perdziola "Der Protagonist: To Be or Not to Be with Der Zar" by Gunther Diehl B OOKS 16 The New Grove Dictionary of Opera Andrew Porter Michael Kater's Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany Susan C. Cook Jilrgen Schebera's Gustav Brecher und die Leipziger Oper 1923-1933 Christopher Hailey PERFORMANCES 19 Britten/Weill Festival in Aldeburgh Patrick O'Connor Seven Deadly Sins at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Paul Young Mahagonny in Karlsruhe Andreas Hauff Knickerbocker Holiday in Evanston. IL bntce d. mcclimg "Nanna's Lied" by the San Francisco Ballet Paul Moor Seven Deadly Sins at the Utah Symphony Bryce Rytting R ECORDINGS 24 Symphonies nos. 1 & 2 on Philips James M. Keller Ofrahs Lieder and other songs on Koch David Hamilton Sieben Stucke aus dem Dreigroschenoper, arr. by Stefan Frenkel on Gallo Pascal Huynh C OLUMNS Letters to the Editor 5 Around the World: A New Beginning in Dessau 6 1993 Grant Awards 4 Above: Georg Kaiser looks down at Weill posing for his picture on the 1928 Leipzig New Publications 15 Opera set for Der Zar /iisst sich pltotographieren, surrounded by the two Angeles: Selected Performances 27 Ilse Koegel 0efl) and Maria Janowska (right). Below: The Czar and His Attendants, costume design for t.he Santa Fe Opera by Robert Perdziola. -

Songs of Kurt Weill

\ Ethan Blake BM Vocal Performance Paradise Valley, Arizbna Justin Carpenter DMA Vocal Performance Tempe, Arizona Gabriella Cavalcanti BM Vocal Performance Tucson, Arizor;ia Chelsea Chimilar MM Vocal Pert. Pedagogy East St. Paul, MB Haeju Choi DMA Collaborative Piano Seoul, Soutt\._K1 SONGS OF KURT WEILL Julia Davis BM Music Theater Anthem, Ariz~a Philip Godfrey BM Vocal Performance Ahwatukee, Arizona Olivia Gardner MM Vocal Performance Mesa, Arizona David Hopkins MM Music Theater Savanah, Georgia Zhou Jiang DMA Collaborative Piano Kunming, CHINA Aaron T. Jones MM Opera Theater Richmond, Virginia Titus Kautz MM Music Theater Bridgeport, Nebraska 1 'i Rina Kim DMA Collaborative Piano Toronto, ON Canada Erin Kong BM Music Theater Chandler, Arizona Juhyun Lee DMA Collaborative Piano lncheon, South Korea Danielle Mendelson BM Vocal Performance Dallas, Texas Nicholas Medrano BM Music Education Scottsdale, Arizona Julian Mendoza BM Music Theater Phoenix, Arizona Vaibu Mohan BM Music Theater Phoenix, Arizona Rex Morris MM Music Theater Baton Rouge, Louisiana Mary Price MM Collaborative Piano Marion, Alabama Christopher Reah BM Music Theater Anthem, Arizona Mariah Rosario BM Vocal Performance Tucson, Arizona Analise Rosario BM Music Theater Tucson, Arizona Kaitlyn Russell BM Music Theater Tucson, Arizona Sara Sanderson BM Music Theater Tucson, Arizona Boston Scott BM Music Theater Scottsdale, Arizona Nathan Shepperd BM Music Theater Phoenix, Arizona Drake Sherman BM Vocal Performance Tucson, Arizona Amanda Sherrill MM Collaborative Piano Orlando~rida Juhee Seo DMA Vocal Performance Seoul, Sou~orea Yeojin Seol DMA Collaborative Piano Seoul, South Korea Melody Startzell BM Vocal Performance Prescott, Arizona Samuel Stefanski BM Vocal Performance Glendale, Arizona Kehui Wu DMA Vocal Performance Hengyong, China Monday • October 17, 2016 • ASU Organ Hall • 7:30pm Ch anashan. -

Checklist for "DA 335: Dance & Society II" with Assistant Professor of Dance Jason Ohlberg the Frances Young Tang

The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College Checklist for "DA 335: Dance & Society II" with Assistant Professor of Dance Jason Ohlberg Costas Cacaroukas Kay Mazzo and Peter Martins in "Violin Concerto", n.d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.86 Costas Cacaroukas Suzanne Farrell on Peter Martins photograph 10 x 8 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.212 Steven Caras Kay Mazzo and Peter Martins in "Violin Concerto", n.d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.81 Fred Fehl Melissa Hayden and Roland Vazquez in "Midsummer's Night Dream", n.d. gelatin silver print 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.125 Carolyn George Suzanne Farrell, n.d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.76 Carolyn George Allegra Kent and Bart Cook in "Episodes", n.d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.170 George Platt Lynes André Eglevsky, Diana Adams, Maria Tallchief, Tanaquil LeClercq in "Apollon Musagète", 1951 photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.95 Martha Swope Suzanne Farrell and Arthur Mitchell in "Metastaseis and Pithoprakta", n. d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.70 Martha Swope Four pairs of dancers, n.d. photograph 8 x 10 in. Gift of Robert Tracy, Class of 1977 1986.97 Martha Swope Diana Adams with Arthur Mitchell in "Agon", n.d.