Because It Is There

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talk 8 at State Episode 8: Getting Outside with Abby Hepp Transcript

Talk 8 at State Episode 8: Getting Outside with Abby Hepp Transcript Eliza Barsanti: Welcome to the department of Health and Exercise Studies’ Talk 8 at State Podcast with your host, Eliza Barsanti! EB: A couple weeks into the Fall 2020 semester, Covid-19 precautions caused NC State to put all classes online. This switch caused a lot of change in the lives of NC State students, forcing them to step out of their typical day-to-day routines in favor of something different. Abby Hepp ‘23 took this as an opportunity to go on the adventure of a lifetime-hiking, camping, and climbing her way across the United States! Today, we sit down with her to talk about her cross-country road trip, along with advice and NC State resources that students can use to get outside and craft their own adventures. EB: Okay, so today we are sitting down with Abby Hepp. Abby, would you like to introduce yourself to the podcast? Abby Hepp: Hi my name is Abby Hepp, I am majoring in Communication Media at NC State and I'm currently a sophomore. EB: Awesome! So we're going to get right into it! Today we're going to be talking about some of your adventures that you've been going on in the past few years and using to inspire other people as well, so let's start with- how did you become involved in outdoor activities and adventuring initially? AH: First of all, thank you for having me and initially will growing up, I would say my family was moderately active and you know I kind of had the typical playing outside with the neighbors childhood. -

Mountains, Streams, and Lakes of Oklahoma I

Information Series #1, June 1998 Mountains, Streams, and Lakes of OklahomaI Kenneth S. Johnson2 INTRODUCTION valleys, hills, and plains throughout most of the re mainder of Oklahoma (Fig. 1). All the major lakes and Mountains and streams define the landscape of reservoirs of Oklahoma are man-made, and they are Oklahoma (Fig. 1). The mountains consist mainly of important for flood contr()l, water supply, recreation, resistant rock masses that were folded, faulted, and and generation of hydroelectric power. Natural lakes thrust upward in the geologic past (Fig. 2), whereas in Oklahoma are limited to oxbow lakes along major the streams have persisted in eroding less-resistant streams and to playa lakes in the High Plains region rock units and lowering the landscape to form broad of the west. Alphabetical List of20 Lakes with Largest Surface Area (from Oklahoma Water Atlas, Oklahoma Water Resources Board) 1. Broken Bow 11. Lake 0' The Cherokees 2. Canton 12. Oologah 3. Eufaula 13. Robert s. Kerr 4. Fort Gibson 14. Sardis 5. Foss 15. Skiatook 6. Great Salt Plains 16. Tenkiller Ferry ·7. Hudson 17. Texoma 8. Hugo 18. Waurika 9. Kaw 19. Webbers Falls 10. Keystone 20. Wister Modified from Historical Atlas of Oklahoma, by John W. Morris, Charles R. Goins, and Edwin C. 25 McReynolds. Copyright © 1986 by the University I of Oklahoma Press. o 40 80Km Figure 1. Mountains, streams, and principal lakes of Oklahoma. lReprinted from Oklahoma Geology Notes (1993), vol. 53, no. 5, p. 180-188. The Notes article was reprinted and expanded from Oklahoma Almanac, 1993-1994, Oklahoma Department of Lihraries, p. -

Geologic Maps of the Eastern Alaska Range, Alaska, (44 Quadrangles, 1:63360 Scale)

Report of Investigations 2015-6 GEOLOGIC MAPS OF THE EASTERN ALASKA RANGE, ALASKA, (44 quadrangles, 1:63,360 scale) descriptions and interpretations of map units by Warren J. Nokleberg, John N. Aleinikoff, Gerard C. Bond, Oscar J. Ferrians, Jr., Paige L. Herzon, Ian M. Lange, Ronny T. Miyaoka, Donald H. Richter, Carl E. Schwab, Steven R. Silva, Thomas E. Smith, and Richard E. Zehner Southeastern Tanana Basin Southern Yukon–Tanana Upland and Terrane Delta River Granite Jarvis Mountain Aurora Peak Creek Terrane Hines Creek Fault Black Rapids Glacier Jarvis Creek Glacier Subterrane - Southern Yukon–Tanana Terrane Windy Terrane Denali Denali Fault Fault East Susitna Canwell Batholith Glacier Maclaren Glacier McCallum Creek- Metamorhic Belt Meteor Peak Slate Creek Thrust Broxson Gulch Fault Thrust Rainbow Mountain Slana River Subterrane, Wrangellia Terrane Phelan Delta Creek River Highway Slana River Subterrane, Wrangellia Terrane Published by STATE OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL & GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS 2015 GEOLOGIC MAPS OF THE EASTERN ALASKA RANGE, ALASKA, (44 quadrangles, 1:63,360 scale) descriptions and interpretations of map units Warren J. Nokleberg, John N. Aleinikoff, Gerard C. Bond, Oscar J. Ferrians, Jr., Paige L. Herzon, Ian M. Lange, Ronny T. Miyaoka, Donald H. Richter, Carl E. Schwab, Steven R. Silva, Thomas E. Smith, and Richard E. Zehner COVER: View toward the north across the eastern Alaska Range and into the southern Yukon–Tanana Upland highlighting geologic, structural, and geomorphic features. View is across the central Mount Hayes Quadrangle and is centered on the Delta River, Richardson Highway, and Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS). Major geologic features, from south to north, are: (1) the Slana River Subterrane, Wrangellia Terrane; (2) the Maclaren Terrane containing the Maclaren Glacier Metamorphic Belt to the south and the East Susitna Batholith to the north; (3) the Windy Terrane; (4) the Aurora Peak Terrane; and (5) the Jarvis Creek Glacier Subterrane of the Yukon–Tanana Terrane. -

Annual Climate Monitoring Report for Denali National Park and Preserve, Wrangell-St-Elias National Park and Preserve and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve

Annual Climate Monitoring Report for Denali National Park and Preserve, Wrangell-St-Elias National Park and Preserve and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve Pamela J. Sousanes Denali National Park and Preserve P.O. Box 9 Denali Park, AK 99755 2005 Central Alaska Network NPS Report Series Number: NPS/AKCAKN/NRTR-2006/0xx Project Number: CAKN-xxxxxx Funding Source: Central Alaska Network Denali National Park and Preserve Draft 2005 Annual Climate Monitoring Report – March 2006 Central Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network File Name: Sousanes_P_2006_ClimateMonitoringCAKN_0315.doc Recommended Citation: Sousanes, Pamela J. 2006. Annual Climate Monitoring Report for Denali National Park and Preserve, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, and Yukon- Charley Rivers National Preserve. NPS/AKCAKN/NRTR-2006/xx. National Park Service. Denali Park, AK. 75 pg. Acronyms: I&M Inventory and Monitoring CAKN Central Alaska Network DENA Denali National Park and Preserve WRST Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve YUCH Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve NPS National Park Service WRCC Western Regional Climate Center NRCS Natural Resources Conservation Service NWS National Weather Service RAWS Remote Automated Weather Station NCDC National Climatic Data Center AWOS Automated Weather Observation Station SNOTEL Snow Telemetry ii Draft 2005 Annual Climate Monitoring Report – March 2006 Central Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................. -

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

Changes in Geyser Eruption Behavior and Remotely Triggered Seismicity in Yellowstone National Park Produced by the 2002 M 7.9 Denali Fault Earthquake, Alaska

Changes in geyser eruption behavior and remotely triggered seismicity in Yellowstone National Park produced by the 2002 M 7.9 Denali fault earthquake, Alaska S. Husen* Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, USA R. Taylor National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming 82190, USA R.B. Smith Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, USA H. Healser National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming 82190, USA ABSTRACT STUDY AREA Following the 2002 M 7.9 Denali fault earthquake, clear changes in geyser activity and The Yellowstone volcanic field, Wyoming, a series of local earthquake swarms were observed in the Yellowstone National Park area, centered in Yellowstone National Park (here- despite the large distance of 3100 km from the epicenter. Several geysers altered their after called ‘‘Yellowstone’’), is one of the larg- eruption frequency within hours after the arrival of large-amplitude surface waves from est silicic volcanic systems in the world the Denali fault earthquake. In addition, earthquake swarms occurred close to major (Christiansen, 2001; Smith and Siegel, 2000). geyser basins. These swarms were unusual compared to past seismicity in that they oc- Three major caldera-forming eruptions oc- curred simultaneously at different geyser basins. We interpret these observations as being curred within the past 2 m.y., the most recent induced by dynamic stresses associated with the arrival of large-amplitude surface waves. 0.6 m.y. ago. The current Yellowstone caldera We suggest that in a hydrothermal system dynamic stresses can locally alter permeability spans 75 km by 45 km (Fig. -

Everest and Oxygen—Ruminations by a Climber Anesthesiologist by David Larson, M.D

Everest and Oxygen—Ruminations by a Climber Anesthesiologist By David Larson, M.D. Gaining Altitude and Losing Partial Pressure with Dave and Samantha Larson Dr. Dave Larson is an obstetric anesthesiologist who practices at Long Beach Memorial Medical Center, and his daughter Samantha is a freshman at Stanford University. Together they have successfully ascended the Seven Summits, the tallest peaks on each of the seven continents, a feat of mountaineering postulated in the 1980s by Richard Bass, owner of the Snowbird Ski Resort in Utah. Bass accomplished it first in 1985. Samantha Larson, who scaled Everest in May 2007 (the youngest non-Sherpa to do so) and the Carstensz Pyramid in August 2007, is at age 18 the youngest ever to have achieved this feat. Because of varying definitions of continental borders based upon geography, geology, and geopolitics, there are nine potential summits, but the Seven Summits is based upon the American and Western European model. Reinhold Messner, an Italian mountaineer known for ascending without supplemental oxygen, postulated a list of Seven Summits that replaced a mountain on the Australian mainland (Mount Kosciuszko—2,228 m) with a higher peak in Oceania on New Guinea (the Carstensz Pyramid—4,884 m). The other variation in defining summits is whether you define Mount Blanc (4,808 m) as the highest European peak, or use Mount Elbrus (5,642 m) in the Caucasus. Other summits include Mount Kilimanjaro in Kenya, Africa (5,895 m), Vinson Massif in Antarctica (4,892 m), Mount Everest in Asia (8,848 m), Mount McKinley in Alaska, North America (6,194 m), and Mount Aconcagua in Argentina, South America (6,962 m). -

8 Arizona Ranges Guide No. 8.2 Humphreys Peak 12633 Feet

8 ARIZONA RANGES GUIDE NO. 8.2 HUMPHREYS PEAK 12633 FEET CLASS 1 MILEAGE: 500 miles of paved road DRIVE/ROUTE A: From Flagstaff, AZ drive about 8 miles N on US Highway 180 to the signed road for the Arizona Snow Bowl Ski Area. Turn right and drive about 7 miles to the ski lodge and park. There is a gate across the road 0.25 miles before the lodge that might be locked. If it is, you'll have to walk the last bit to the ski lodge. CLIMB/ROUTE A: The start of the Humphreys Peak Trail is located just N of the Agassiz Peak lower chair lift station. Follow the trail as it switchbacks up the SW flank of Humphreys Peak to the summit ridge and then N to the top. This fairly new trail was completed in 1984 and is the shortest "legal" route to the summit (See SIDELINES 3 below). ROUND TRIP STATS/ROUTE A: 3200 feet elevation gain, 10 miles, 8 hours DRIVE/ROUTE B: From the intersection of Highways 89 and 180 in Flagstaff, drive about 3 miles N on US Highway 180 to the signed, paved Schultz Pass Road (Forest road #420). Turn right (N) here and drive 5.5 miles to Schultz Pass. Park near Schultz Tank, a pond just S of the road. Forest road #522 heading N from here marks the start of the Weatherford trail. CLIMB/ROUTE B: Follow the trail over Fremont and Doyle saddles to where it joins the Humphreys Peak Trail near the Humphreys-Agassiz saddle. -

Black Elk Peak Mobile Scanning Customers & Services Definitive Elevation Bringing the Goods TRUE ELEVATION BLACK ELK PEAK » JERRY PENRY, PS

MAY 2017 AROUND THE BEND Survey Economics Black Elk Peak Mobile Scanning Customers & services Definitive elevation Bringing the goods TRUE ELEVATION BLACK ELK PEAK » JERRY PENRY, PS Displayed with permission • The American Surveyor • May 2017 • Copyright 2017 Cheves Media • www.Amerisurv.com lack Elk Peak, located in the Black Hills region of South Dakota, is the state’s highest natural point. It is frequently referred to as the highest summit in the United States east of the Rocky BMountains. Two other peaks, Guadalupe Peak in Texas and Sierra Blanca Peak in New Mexico, are higher and also east of the Continental Divide, but they are P. Tuttle used a Green’s mercury barometer, one of the considered south of the Rockies. best instruments of the time to determine elevations on The famed Black Elk Peak was known as Harney high peaks. Tuttle coordinated his measurements with Peak as early as 1855 in honor of General William S. simultaneous readings at the Union Pacific Railroad Harney. This designation lasted for more than 160 depot in Cheyenne, Wyo. The difference between the two years, but the peak was renamed Black Elk Peak on barometer readings, when added to the known sea level August 11, 2016, by the U. S. Board of Geographic elevation at Cheyenne, resulted in elevations of 7369.4’ Names to honor medicine man Black Elk of the Oglala and 7368.4’, varying greatly from the 9700’ elevation Lakota (Sioux). The two names are synonymously used previously obtained by Ludlow. in this article as the same peak. The elevation results of the Newton-Jenney The first attempt to accurately measure the elevation of Expedition were not published until 1880 due to the Black Elk Peak was in 1874 during the Custer Expedition. -

Encounters with the Early Highpointers by Charles

SOME CLOSE (AND NOT SO CLOSE) ENCOUNTERS WITH THE EARLY HIGHPOINTERS BY CHARLES FERIS Many stories can be told of how we got our first inspiration to pursue this hobby of ours, this highpointing. We’ve been inspired in a hundred ways; mine arose during a period of boredom, while in college. Seeking something other than study, I took out a Rand McNally road atlas, and looked at a map of my native state of Illinois, noting the little red dot in the northwest corner of the state. Wow, something neat to do. So while the other kids were off to Florida, off to Charles Mound I went during spring break 1961. Then it hit me; I had already done Mt. Whitney the year before, so why not do all the states. Now I was really excited. The next few years saw me collecting 13 more highpoints in the Midwest and southeast. I went my merry way, never realizing that others might be crazy enough to be pursuing the very same project. At this point I was not aware of the tiny fraternity of early highpointers who were already years before me. I had no idea of the remarkable people I was about to meet. Then in August 1965 a Sierra Club friend of mine in Chicago told me about C. Rowland Stebbins. I had found a kindred soul, one who had already completed the 48. I phoned him immediately. Soon my wife and I were off on the four hour drive to Lansing, Michigan. We arrived to an expansive mansion on Moore’s River Drive atop a bluff overlooking the Grand River. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking ``x'' in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter ``N/A'' for ``not applicable.'' For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name East Longs Peak Trail; Longs Peak Trail; Keyhole Route; Shelf Trail other names/site number 5LR.11413; 5BL.10344 2. Location street & number West of State Highway 7 (ROMO) [N/A] not for publication city or town Allenspark [X] vicinity state Colorado code CO county Larimer; Boulder code 069; 013 zip code 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [ ] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [ ] nationally [ ] statewide [X] locally. -

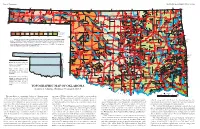

TOPOGRAPHIC MAP of OKLAHOMA Kenneth S

Page 2, Topographic EDUCATIONAL PUBLICATION 9: 2008 Contour lines (in feet) are generalized from U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps (scale, 1:250,000). Principal meridians and base lines (dotted black lines) are references for subdividing land into sections, townships, and ranges. Spot elevations ( feet) are given for select geographic features from detailed topographic maps (scale, 1:24,000). The geographic center of Oklahoma is just north of Oklahoma City. Dimensions of Oklahoma Distances: shown in miles (and kilometers), calculated by Myers and Vosburg (1964). Area: 69,919 square miles (181,090 square kilometers), or 44,748,000 acres (18,109,000 hectares). Geographic Center of Okla- homa: the point, just north of Oklahoma City, where you could “balance” the State, if it were completely flat (see topographic map). TOPOGRAPHIC MAP OF OKLAHOMA Kenneth S. Johnson, Oklahoma Geological Survey This map shows the topographic features of Oklahoma using tain ranges (Wichita, Arbuckle, and Ouachita) occur in southern contour lines, or lines of equal elevation above sea level. The high- Oklahoma, although mountainous and hilly areas exist in other parts est elevation (4,973 ft) in Oklahoma is on Black Mesa, in the north- of the State. The map on page 8 shows the geomorphic provinces The Ouachita (pronounced “Wa-she-tah”) Mountains in south- 2,568 ft, rising about 2,000 ft above the surrounding plains. The west corner of the Panhandle; the lowest elevation (287 ft) is where of Oklahoma and describes many of the geographic features men- eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas is a curved belt of forested largest mountainous area in the region is the Sans Bois Mountains, Little River flows into Arkansas, near the southeast corner of the tioned below.