Answer Brief of Appellee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

589 Thesis in the Date of Tomb TT 254 Verification Through Analysis Of

Thesis in The Date Of Tomb TT 254 Verification Through Analysis of its Scenes Thesis in The Date of Tomb TT 254 Verification through Analysis of its Scenes Sahar Mohamed Abd el-Rahman Ibrahim Faculty of Archeology, Cairo University, Egypt Abstract: This paper extrapolates and reaches an approximate date of the TOMB of TT 254, the tomb of Mosi (Amenmose) (TT254), has not been known to Egyptologists until year 1914, when it was taken up from modern occupants by the Antiquities Service, The tomb owner is Mosi , the Scribe of the treasury and custodian of the estate of queen Tiye in the domain of Amun This tomb forms with two other tombs (TT294-TT253) a common courtyard within Al-Khokha necropolis. Because the Titles/Posts of the owner of this tomb indicated he was in charge of the estate of Queen Tiye, no wonder a cartouche of this Queen were written among wall paintings. Evidently, this tomb’s stylistic features of wall decorations are clearly influenced by the style of Amarna; such as the male figures with prominent stomachs, and elongated heads, these features refer that tomb TT254 has been finished just after the reign of Amenhotep IV (Akhenatun). Table stands between the deceased and Osiris which is divided into two parts: the first part (as a tray) is loading with offerings, then the other is a bearer which consisted of two stands shaped as pointed pyramids… based on the connotations: 1- Offerings tables. 2- Offerings Bearers. 3- Anubis. 4- Mourners. 5- Reclamation of land for cultivation. 6- Banquet in some noble men tombs at Thebes through New Kingdom era. -

+Tư Tưởng Hồ Chí Minh

BỘ GIÁO DỤC VÀ ĐÀO TẠO CỘNG HÒA XÃ HỘI CHỦ NGHĨA VIỆT NAM TRƯỜNG ĐẠI HỌC HÀ NỘI Độc lập - Tự do - Hạnh phúc DANH SÁCH DỰ THI KẾT THÚC HỌC PHẦN TƯ TƯỞNG HỒ CHÍ MINH Hệ đào tạo: Đại học chính quy -Năm học: 2020-2021- Học kỳ I Phòng thi: 602 - Nhà C; Ngày thi: 08.11.2020; Ca 1 (13:00 - 14:20) Stt SBD Mã sv Họ và Tên Ngày sinh Lớp Mã đề Điểm Ký tên Ghi chú 1 TT01 1704000001 Hoàng An 10/04/1999 4K-17 2 TT02 1907040001 Nguyễn Thị Thanh An 16/06/2001 1T-19 3 TT03 1907070001 Nguyễn Thị An 17/07/2000 1H-19 4 TT04 1907170001 Nguyễn Thị Hà An 01/01/2001 1H-19C 5 TT05 1807010048 Nguyễn Hồng Ân 08/06/2000 4A-18 6 TT06 1604000009 Trần Thị Vân Anh 28/11/1998 1K-17 7 TT07 1701040003 Bùi Tuấn Anh 04/12/1999 1C-17 8 TT08 1704000003 Đào Minh Anh 18/06/1999 4K-17 9 TT09 1704000009 Nguyễn Hữu Tuấn Anh 16/09/1999 4K-17 10 TT10 1704000011 Nguyễn Minh Anh 17/10/1999 3K-17 11 TT11 1704040009 Nguyễn Tuấn Anh 05/11/1999 1TC-17 12 TT12 1706080012 Nguyễn Phương Anh 15/07/1999 1Q-17 13 TT13 1706090009 Phạm Thị Vân Anh 08/02/1999 2D-17 14 TT14 1707010018 Nguyễn Mai Anh 12/10/1999 10A-17 15 TT15 1707020003 Hoàng Vân Anh 30/11/1999 1N-17 16 TT16 1707100001 Đinh Hải Anh 28/10/1999 1B-17 17 TT17 1707100003 Nguyễn Hà Anh 19/06/1999 2B-17 18 TT18 1801000005 Nguyễn Phương Anh 17/03/2000 2TT-18 19 TT19 1801000007 Nguyễn Thị Phương Anh 08/12/2000 1TT-18 20 TT20 1801040013 Vũ Thị Phương Anh 26/08/2000 4C-18 21 TT21 1804000001 Đoàn Hải Anh 18/04/2000 2K-18 22 TT22 1804000004 Nguyễn Mai Anh 02/10/2000 2K-18 23 TT23 1804000008 Trần Mai Anh 22/04/2000 1K-18 24 TT24 1804010006 Lê -

2013: Cincinnati, Ohio

The 64th Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt April 19-21, 2013 Hilton Netherland Plaza Cincinnati, OH Abstract Booklet layout and design by Kathleen Scott Printed in San Antonio on March 15, 2013 All inquiries to: ARCE US Office 8700 Crownhill Blvd., Suite 507 San Antonio, TX 78209 Telephone: 210 821 7000; Fax: 210 821 7007 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.arce.org ARCE Cairo Office 2 Midan Simon Bolivar Garden City, Cairo, Egypt Telephone: 20 2 2794 8239; Fax: 20 2 2795 3052 E-mail: [email protected] Photo Credits Front cover: Cleaned wall reliefs at Deir el Shelwit. Photo Abdallah Sabry. Photo opposite: Relief detail Deir el Shelwit. Photo Kathleen Scott. Photo spread pages 8-9: Conservators working inside Deir el Shelwit October 2012. Photo Kathleen Scott. Abstracts title page: Concrete block wall with graffiti outside ARCE offices February 2013. Photo Kathleen Scott. Some of the images used in this year’s Annual Meeting Program Booklet are taken from ARCE conservation projects in Egypt which are funded by grants from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). MEET, MINGLE, AND NETWORK Rue Reolon, 12:30pm - 1:30pm Exploding Bunnies and Other Tales of Caution (a forum of experts) ARCE Chapter Council 2013 Fundraiser You have heard the scientific lectures; the reports of long, hard, and sometimes even dull archaeological work that produces the findings that all Egyptophiles crave. But there is more! Now enjoy stories of the bizarre, unexpected, and obscure, presented by our panel of experts. Saturday, April 20, 2013 12:15 - 1:00 pm Pavilion Ballroom, 4th Floor Hilton Netherland Plaza Hotel $15 per Person ARCHAEOLOGIA BOOKS & PRINTS With selections from the libraries of Raymond Faulkner, Harry Smith & E. -

The Symbolism and Function of the Window of Appearance in the Amarna Period*1

FOLIA PRAEHISTORICA POSNANIENSIA T. XXIV – 2019 WYDZIAŁ ARCHEOLOGII, UAM POZNAŃ – ISSN 0239-8524 http://dx.doi.org/10.14746/fpp.2019.24.05 THE SYMBOLISM AND FUNCTION OF THE WINDOW OF APPEARANCE IN THE AMARNA PERIOD*1 SYMBOLIZM I FUNKCJA OKNA POJAWIEŃ W OKRESIE AMARNEŃSKIM Maria M. Kloska orcid.org/0000-0003-4822-8891 Wydział Historii, Uniwersytet im. A. Mickiewicza ul. Uniwersytetu Poznańskiego 7, 61-614 Poznań [email protected] ABSTRACT: During the reign of the Amarna spouses, giving gold necklaces to royal officials took place (almost always) from the so-called Window of Appearance. From them, Akhenaten and Nefertiti, often with princesses, honoured deserved and devoted dignitaries. The popularity of the Window of Appearance closely relates to the introduction of a new religious system introduced by Akhenaten and Nefertiti. Ac- cording to the new religion, Akhenaten and Nefertiti were a pair of divine twins like Shu and Tefnut, who in the Heliopolitan theology, were the children of the god Atum – replaced by Aten in Amarna. The royal couple prayed to the main solar god, while their subjects prayed to the king and queen. Since Akhenaten per- formed the role of a priest through whom ordinary people could pray to the god, it was necessary to create a construction that would allow the king to meet with his subjects publicly. The Window of Appearance was such architectural innovation. It was crucial because the king was an intermediator between the peo- ple and the only right sun god, Aten. The Windows of Appearance were probably located in various places in Akhetaten, including the Great Palace, the King’s House, the North Palace, the Small Aten Temple and in the temples of the Sunshades of Re in the Kom el-Nana and Maru-Aten. -

Flood Risk Assessment Report

Consulng Civil, Structural & Geo-Environmental Engineers Flood Risk Assessment Report Site Address: Burnley Road Rawtenstall Lancashire Paul Waite Associates Ltd Summit House Riparian Way Project Ref: 13161/I/01A The Crossing Cross Hills February 2014 BD20 7BW [email protected] www.pwaite.co.uk Report No.13161/1/01 Project Details. FRA – Site off Burnley Road, Rawtenstall, Lancashire Date. November 13 Flood Risk Assessment Paul Waite Associates have been appointed by the RTB Partnership, to undertake a Flood Risk Assessment in support of a planning application for residential development at a site off Burnley Road in Rawtenstall, Lancashire. Clients Details RTB Partnership The Business Centre Futures Park Bacup Lancashire OL13 0BB Documents Revision Status ISSUE: DATE COMMENTS ‐ November 4, 2013 FINAL A February 10, 2014 FINAL ‐ Revised following updated development plans Report No.13161/1/01 Project Details. FRA – Site off Burnley Road, Rawtenstall, Lancashire Date. November 13 Contents Executive Summary 1 1.0 Introduction 3 2.0 Approach to the Flood Risk Assessment 4 2.1 Approach 4 2.2 Application of the Sequential and Exceptions Test 4 3.0 Site Details 6 3.1 Location 6 3.2 Former/Current Use 6 3.3 Proposals 6 3.4 Boundaries 7 3.5 Topography 7 3.6 Existing Drainage 8 3.7 History of Flooding 9 3.7.1 British Hydrological Society – Hydrological Events 9 3.7.2 Internet Search for Historical Flooding 9 3.7.3 Lancashire Area PFRA Document (2011) 9 3.7.4 Rossendale Borough Council SFRA (May 2009) 11 3.7.5 Environment Agency Data – Historic Flooding 11 4.0 Flooding Mechanisms 12 4.1 Fluvial: Limy Water 12 4.1.1 General 12 4.1.2 Modeled Flood Level Data 13 4.1.3 Overtopping 14 4.1.4 Climate Change 15 4.1.5 Infrastructure Failure: Blockage 16 4.1.6 Conclusion 17 4.2 Artificial Water Sources: Reservoirs 17 4.3 Pluvial Sources 18 4.3.1 Sewer Flooding 18 4.3.2 Increase in Surface Water Runoff 19 Report No.13161/1/01 Project Details. -

Resettlement and Ethnic Minority Development Plan (REMDP) VIE

Resettlement and Ethnic Minority Development Plan (REMDP) Stage of the document: Final Project number: 49026-002 April 2017 VIE: Basic Infrastructure for Inclusive Growth in the Northeastern Provinces Sector Project-Upgrading and Improvement of Provincial Road 184, Dong Tam Commune, Bac Quang District to Ngoc Linh Commune, Vi Xuyen District, Ha Giang Province Prepared by Planning and Investment Department of Ha Giang province for the Asian Development Bank. i ii CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 27 April 2017) Currency unit – Viet Nam Dong (D) D1.00 = $0.000044 $1.00 = Ð 22,730 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank AH - Affected Household AP - Affected Person CARB - Compensation, Assistance and Resettlement Board CPC - Commune People’s Committee DARD - Department of Agriculture and Rural Development DMS - Detailed Measurement Survey DOF - Department of Finance DONRE - Department of Natural Resources and Environment DPC - District Peoples, Committee DPI - Department of Planning and Investment DRC District Resttlement Committee EA - Executing Agency EM - Ethnic Minority FS - Feasibility Study GOV - Government of Vietnam HH - Household IMO Independent Monitoring Organization IOL - Inventory of Losses LIC - Loan Implementation Consultants LFDC Land Fund Development Center LURC - Land Use Rights Certificate MOF - Ministry of Finance MOLISA - Ministry of Labor, Invalids and Social Assistance MONRE - Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment MPI - Ministry of Planning and Investment NTP - Notice to Proceed PIB - Project Information Booklet -

North Carolina, C. 1800?, 32Wx42h) Carlyle Lynch, Drawn by 1982, 1991 Plan American Plans 02 Dressing Glass (South Carolina C

CallNumber Title Author CopyrightYearCommentsMedia Key word 1 Key word 2 Plans 01 Chest of drawers (North Carolina, c. 1800?, 32wx42h) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1982, 1991 Plan American Plans 02 Dressing glass (South Carolina c. 1780 small chest with mirror, 17wx20h) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1982, 1991 Plan American Plans 03 Duncan Phyfe's tool chest (New York chest-within-a-chest c. 1790's, 26hx 39w) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1985, 1991 Plan American Plans 04 John Marshall's Desk (Virginia c. 1800?, 42hx42wx24d) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1974, 1990 Plan American Plans 05 Linen Press (North Carolina c. 1780, 77hx37wx19d) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1987, 1990 Plan American Plans 06 Moravian Blanket Chest (North Carolina c. 1780, 22hx42wx22d) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1980 Plan American Plans 07 Moravian footstool and Hanging shelves (North Carolina c. late 1700's; footstool Carlyle18wx6hx7d, Lynch, shelves drawn 35hx28wx11d)by 1981, 1990 Plan American Plans 08 Pencil Post Bed (New England c. 1800?) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1978, 1990 Plan American Plans 09 Queen Anne Highboy (New England mid 1700's; 72hx38wx19d) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1974, 1991 Plan American Plans 10 Sideboard table (Chinese Chippendale style c. 1760, 48wx31hx24d) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1974, 1991 Plan American Plans 11 Six-board chest (North Carolina c. 1800, 25hx38w) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1973, 1990 Plan American Plans 12 Tidewater stand and Albemarle chest (Chippendale-style side table c. 1770 28hx19w;Carlyle miniature Lynch, drawn chest by6hx13w)1987 Plan American Plans 13 Valley of Virginia side table (c. 1790, 29hx21wx21d) Carlyle Lynch, drawn by 1986, 1990 Plan American Plans 14 Virginia Bedstead (Pencil post with foot and headboards c. -

Esschert Drop Ship Program 2020

ESSCHERT DROP SHIP PROGRAM 2020 800.888.0054 | www.griffins.com Terms Net 30 on all drop ship orders - No minimum order- If order is over $300, 15% freight cap east of the Mississippi 20% for west - If order is over $2500, 10% freight cap for east of the Mississippi 15% for west - If order is over $5,000 entire order is freight prepaid Item # VPN Pg Description Dealer UPC Code Cs Pk. Qty 81982719 FB492 4 Bird Feeder w/Cage FB492 $ 19.95 8714982171901 6 81982718 FB491 4 Square Bird Bath w/Birds, Terrazzo FB491 $ 18.95 8714982171895 4 81982717 FB490 4 Round Bird Bath w/Birds, Terrazzo FB490 $ 18.95 8714982171888 4 81982716 FB489 4 Round Bird Bath w/Birds, Ceramic - Green FB489 $ 10.95 8714982171871 4 81982715 FB488 4 Round Bird Bath w/Birds, Ceramic - Petrol FB488 $ 10.95 8714982171864 4 81982714 FB487 4 Round Bird Bath w/Birds, Ceramic - Gray FB487 $ 10.95 8714982171857 4 81982713 FB473 4 Round Bird Bath/Feeder w/Birds, Ceramic, White/Green/Blue, 3 Asst. Colors $ 6.50 8714982164330 4 81982712 FB297 4 Bird Bath w/Birds, Concrete FB297 $ 11.95 8714982098710 4 81982711 FB404 5 Oval Bird Bath w/2 Birds, Ceramic, White/Green/Blue, 3 Asst. Colors FB404 $ 11.95 8714982129698 6 81982710 FB421 5 Bird Bath w/Two Birds, Ceramic, White/Green/Blue, 3 Asst. Colors FB421 $ 10.95 8714982143397 12 81982709 FB422 5 Bird Bath on Pedestal w/Bird, Ceramic, Blue FB422 $ 54.95 8714982143403 2 81982708 FB423 5 Bird Bath on Pedestal w/Bird, Ceramic, White FB423 $ 54.95 8714982143410 2 81982707 FB424 5 Bird Bath on Pedestal w/Bird, Ceramic, Green FB424 $ 54.95 8714982143427 2 81982706 FB443 5 Hanging Ceramic Bird Bath, Cream/Green/Blue, 3 Asst. -

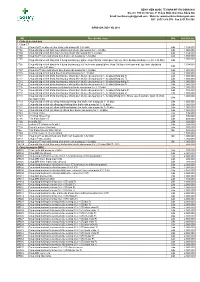

Mã Tên Cận Lâm Sàng Đvt Giá Dịch Vụ 1

BỆNH VIỆN QUỐC TẾ HOÀN MỸ ITO ĐỒNG NAI Địa chỉ: F99 Võ Thị Sáu, P. Thống Nhất, Biên Hòa, Đồng Nai Email: [email protected] - Website: www.benhvienitodongnai.com SĐT: 02513.918.559 - Fax:0253.518.569 BẢNG GIÁ DỊCH VỤ 2018 Mã Tên cận lâm sàng Đvt Giá dịch vụ 1. Chẩn đoán hình ảnh 1. Chụp CT CT02 Chụp CLVT sọ não có tiêm thuốc cản quang (từ 1-32 dãy) Lần 1,154,000 CT03 Chụp cắt lớp vi tính lồng ngực không tiêm thuốc cản quang (từ 1- 32 dãy) Lần 1,000,000 CT04 Chụp cắt lớp vi tính lồng ngực có tiêm thuốc cản quang (từ 1- 32 dãy) Lần 1,154,000 CT08 Chụp CLVT hàm-mặt không tiêm thuốc cản quang (từ 1-32 dãy) Lần 1,000,000 CT05 1,000,000 Chụp cắt lớp vi tính tầng trên ổ bụng thường quy (gồm: chụp Cắt lớp vi tính gan-mật, tụy, lách, dạ dày-tá tràng.v.v.) (từ 1-32 dãy) Lần CT06 Chụp cắt lớp vi tính tầng trên ổ bụng thường quy (có thuốc cản quang)(gồm: chụp Cắt lớp vi tính gan-mật, tụy, lách, dạ dày-tá 1,154,000 Lần tràng.v.v.) (từ 1-32 dãy) CT07 Chụp CLVT hàm-mặt không tiêm thuốc cản quang (từ 1-32 dãy) Lần 1,000,000 CT10 Chụp cắt lớp vi tính bụng-tiểu khung thường quy (từ 1-32 dãy) Lần 1,000,000 CT11 Chụp cắt lớp vi tính khớp thường quy không tiêm thuốc cản quang (từ 1- 32 dãy)(Khớp gối T) Lần 1,000,000 CT12 Chụp cắt lớp vi tính khớp thường quy không tiêm thuốc cản quang (từ 1- 32 dãy)(Khớp vai T) Lần 1,000,000 CT13 Chụp cắt lớp vi tính khớp thường quy không tiêm thuốc cản quang (từ 1- 32 dãy)(Khớp háng T) Lần 1,000,000 CT14 Chụp cắt lớp vi tính khớp thường quy không tiêm thuốc cản quang (từ 1- 32 dãy)(Khớp vai P) Lần 1,000,000 CT15 Chụp -

Viaggio in Egitto - Le Necropoli Tebane Di Antonio Crasto

Viaggio in Egitto - Le necropoli tebane di Antonio Crasto Nell’area occidentale di Waset / Tebe / Luxor esistono varie necropoli: reali (Valle dei Re, Valle Occidentale, Valle delle Regine, ecc.) e di nobili (Asasif, el-Khokha, Shaykh Abd el-Qurna, el- Khokha, Dra Abu el-Naga e Qurnet Murai); templi funerari (Thutmose I, Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV, Amenhotep III, Horemheb, Sethy I, Ramesse II (Ramesseum), Merenptah, Tausert, Siptah e Ramesse III. Esiste inoltre un Villaggio degli operai e artisti a Deir el- Medina, con relativa area abitativa, tempio e necropoli. Luxor West Bank Necropoli di el-Asasif A sud di Deir el Bahari c’è la necropoli di el-Asasif, dove furono scavate varie tombe ipogeiche, principalmente durante la XXV e XXVI dinastia. Presentano un ingresso monumentale, una scalinata e un cortile a 3-4 metri di profondità. Una porta a forma di pilone immette alla zona sotterranea, che presenta una serie di camere e sale collegate da un corridoio, che porta infine alla sala sepolcrale. Fra queste tombe possiamo segnalare quelle di: Montuemhat (TT34), 4° profeta di Amon, principe della città sotto Taharqa e Psammetico I; Ibi (TT36), ciambellano della Divina Adoratrice, Nitocris, sotto Psammetico I; Parennefer (TT188), maggiordomo reale e intendente sotto Amenhotep IV; Pabasa (TT279), gran maggiordomo della Divina Adoratrice, Nitocris, sotto Psammetico I; Jar (TT366), guardiano dell’harem reale sotto Mentuhotep I; Samut (TT409), scriba contabile del bestiame di Amon e delle divinità tebane, sotto Ramesse II; Kheruef (TT192), scriba reale, governatore e depositario del sigillo reale, sotto Amenhotep III; Amenhotep Huy (TT28), sindaco di Menphy e visir. -

Inscription of the 18Th Dynasty Tombs

International Journal of Emerging Engineering Research and Technology Volume 8, Issue 6, 2020, PP 21-31 ISSN 2349-4395 (Print) & ISSN 2349-4409 (Online) Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part 94: Inscription of the 18th Dynasty Tombs Galal Ali Hassaan* Department of Mechanical Design & Production, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt *Corresponding Author: Galal Ali Hassaan, Department of Mechanical Design & Production, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt ABSTRACT This paper investigates the inscription of the tombs of the 18th Dynasty. This era is dived by the author to three divisions: Early, Middle and Late. In each division Royal and Nobel tombs are scanned to extract the philosophy of tomb inscription during this era. A quantitative analysis is performed for reliefs and scenes, Royal and Nobel tombs. The features of tomb inscription are outlined. A total number of 28 scenes and reliefs are studied and quantitatively analysed. Keywords: Mechanical engineering, ancient Egypt, tomb inscription, 18th Dynasty of Egypt INTRODUCTION (2008) in her Master of Arts Thesis presented many artistic works including tomb wall scenes This research paper is the 94th paper in a series as evidence for the roles of elite women in of research papers aiming at investigating the events, practices and rituals. She presented evolution of Mechanical Engineering in ancient scenes for Queen Ahmose, relief for Neithhotep Egypt through studying tomb inscription during hunting scene from tomb of Nefermaat, Medium the Pharaonic era of ancient Egypt. Geese from the tomb of Nefermaat, relief for Afshar (1993) in his study of the iconography Pharaoh Akhenaten and Nefertiti, scene for of the wall paintings in Queen Nefertari Tomb fowling in the marshes from the tomb of outlined that the tomb paintings were accompanied Nebamun, scene of Queen Ahmose Ne-fertari, by hieroglyphic inscriptions from the 'Book of scene of Sennefer and his wife Meryt [4]. -

Amenhotep III to the Death of Ramesses II Notes

HISTORICAL PERIOD: NEW KINGDOM EGYPT FROM AMENHOTEP III TO THE DEATH OF RAMESSES II INTERNAL DEVELOPMENTS REGION OF AMENHOTEP III + ROLE AND CONTRIBUTION - Described by Dr Binder as the climax and turning point in NK – 1390 BC o Contrast to preceding period = period of peace with neighbours, diplomacy, consolidating wealth, building administration o Turning point in religion, innovation and change, art and technology o Berman comments “Egypt was wealthier and more powerful than ever before” – years of peace, strong harvests, steady flow of gold = allowed his innovation to transform the landscape o Protect the already gained peace and prosperity - Diplomacy characterises reign e.g. the Armana letters – other countries sending tribute to show loyalty – called himself “the king of kings” o Even greatest kings of near east were desperate for gold - Direct communication with subjects – ‘propaganda beetles’ o Political significance to promote his strength and power - Ninth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty - Inherited a great empire – didn’t require much work to build it up - Produced lots of source – archeological, inscriptions, iconography - Son of Tuthmosis IV and Queen Mutemwia (secondary wife) o Bark of Mutemwia - Mummy from KV 35 o Elderly upon death o Missy teeth, gums damaged - Thutmoses IV died when he was very young – Mutemwia held power until Amenhotep was of age to rule - Accession to the throne at age 12 -Evidence isn’t conclusive on age - Year 2 of reign = married Queen Tiy (Great Royal Wife) - Year 38 = final year on throne (aged around 50) - Royal family o Great royal wife = Queen Tiy ▪ Wooden head with elaborate headdress of Queen Tiy (Berlin Museum) ▪ Allowed her parents to have a tomb built in the VoK = Yuya and Thuya (KV46) ▪ Sent marriage scarabs around the kingdom (Brookyln museum + national gallery of Victoria) – ensured children would be recognised as legitament ▪ Blue and yellow cosmetic jar with name written Tiy’s name in Cartouche = honour as this was reserved for the pharaoh and signifying universal and eternal rule.