Potential for Growth of Clostridium Perfringens from Spores in Pork Scrapple During Cooling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diet Manual for Long-Term Care Residents 2014 Revision

1 Diet Manual for Long-Term Care Residents 2014 Revision The Office of Health Care Quality is pleased to release the latest revision of the Diet Manual for Long-Term Care Residents. This manual is a premier publication—serving as a resource for providers, health care facilities, caregivers and families across the nation. In long-term care facilities, meeting nutritional requirements is not as easy as it sounds. It is important to provide a wide variety of food choices that satisfy each resident’s physical, ethnic, cultural, and social needs and preferences. These considerations could last for months or even years. Effective nutritional planning, as well as service of attractive, tasty, well-prepared food can greatly enhance the quality of life for long-term care residents. The Diet Manual for Long Term Care Residents was conceived and developed to provide guidance and assistance to nursing home personnel. It has also been used successfully in community health programs, chronic rehabilitation, and assisted living programs. It serves as a guide in prescribing diets, an aid in planning regular and therapeutic diet menus, and as a reference for developing recipes and preparing diets. The publication is not intended to be a nutrition-care manual or a substitute for individualized judgment of a qualified professional. Also included, is an appendix that contains valuable information to assess residents’ nutritional status. On behalf of the entire OHCQ agency, I would like to thank the nutrition experts who volunteered countless hours to produce this valuable tool. We also appreciate Beth Bremner and Cheryl Cook for typing the manual. -

9 CFR Ch. III (1–1–12 Edition) § 316.11

§ 316.11 9 CFR Ch. III (1–1–12 Edition) capacity of 5 kilograms (11.025 lbs.) or products: And provided further, That less and containing a single kind of imitation sausage packed in properly product: Provided, That such products labeled containers having a capacity of in properly labeled closed containers 3 pounds or less and of a kind usually exceeding 5 kilograms (11.025 lbs.) ca- sold at retail intact, need not bear the pacity, when shipped to another offi- word ‘‘imitation’’ on each link or piece cial establishment for further proc- if no other marking or labeling is ap- essing or to a governmental agency, plied directly to the product. need only have the official inspection (b) When cereal, vegetable starch, legend and list of ingredients shown starchy vegetable flour, soy flour, soy twice throughout the contents of the protein concentrate, isolated soy pro- container. When such products are tein, dried milk, nonfat dry milk, or shipped to another official establish- calcium reduced dried skim milk is ment for further processing, the inspec- added to sausage in casing or in link tor in charge at the point of origin form within the limits prescribed in shall identify the shipment to the in- part 319 of this subchapter, the prod- spector in charge at destination by ucts shall be marked with the name of means of Form MP 408–1. each added ingredient, as for example (c) The list of ingredients may be ap- ‘‘cereal added,’’ ‘‘potato flour added,’’ plied by stamping, printing, using ‘‘cereal and potato flour added,’’ ‘‘soy paper bands, tags, or tissue strips, or flour added,’’ ‘‘isolated soy protein other means approved by the Adminis- added,’’ ‘‘nonfat dry milk added,’’ trator in specific cases. -

Livermush Is a Unique Regional Pork Dish That Can Only Be Found in a Small Area of North Carolina

Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ º [Music Througout] º >> [Voice over]: Livermush is a unique regional pork dish that can only be found in a small area of North Carolina. Livermush is made by mixing pork scraps, pork liver, cornmeal, and spices; which are then formed into a brick. The most common way to prepare livermush is to cut the brick into half inch slices and fry them in butter. These slices are often served alone or in between two halves of a biscuit with yellow mustard or grape jelly. The production of livermush has been industrialized in the last century by local companies such as Mack's Livermush & Meats in Shelby, North Carolina and Neese's in Greensboro, North Carolina; but before livermush was mass produced it was made at home. This food tradition is thought to have been brought to Western North Carolina by German immigrants. Germans, like many other Europeans, came to America hoping to build better lives without poverty or persecution. Many Germans first settled in Pennsylvania but then journeyed to the Appalachian mountains of North Carolina. According to the United States Census of 1792 approximately 20,000 Germans were living in North Carolina. This makes up five percent of the population at the time. These Germans took an old dish, pon hoss, from their homeland and made the old recipe work for the new world. Pon Hoss developed into scrapple in Pennsylvania and into livermush in North Carolina. -

Menu for Week

Featured Tsa Tsio (“saat-soo”) (Duroc) $10 per lb. Madagascar's version of Chinese Char Sui pork. Strips of Duroc pork shoulder are cured and marinated overnight in a mix of honey, vanilla-infused rum, our house- made Chinese 5-spice and a little Madagascar-style hot sauce. Enjoy like jerky or slice & use in sandwiches, ramen, salads etc. Pulled Pork (Berkshire) $8 per lb. Whole local Berkshire pork shoulders rubbed with salt and pepper for 2 days. Cold-smoked for 8 hours over a real wood fire of oak and fruitwoods. Then roasted very low and very slow in an oven overnight. Scottish Black Pudding $8 per lb. Traditional blood pudding from Scotland thickened with milk-cooked oats and seasoned with bacon ends, sage and allspice. Ready for a fry up. Smoked Candied Peanuts $4 per đ lb. pack Sweet, crunchy and just a touch of heat. BACONS Brown Sugar Beef Bacon (Piedmontese beef) $9 per lb. (sliced) Grass-fed local Piedmontese beef belly dry- cured for 10 days, coated with black pepper, glazed with brown sugar and smoked over oak and juniper woods. Traditional Bacon (Duroc) $8 per lb. (sliced) No sugar. No nitrites. Nothing but pork belly, salt and smoke. Thick cut traditional dry-cured bacon smoked over a real fire of oak and fruitwoods. Garlic Bacon (Duroc) LIMITED $8 per lb. (sliced) Dry-cured Duroc pork belly coated with garlic and smoked over real wood fire. Black Crowe Bacon (our house bacon) (Duroc) $9 per lb. Dry-cured double-smoked bacon seasoned with black pepper, coffee grounds, garlic and Ancho chili. -

Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 22, No. 3 Burt Feintuch

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection Spring 1973 Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 22, No. 3 Burt Feintuch Susan J. Ellis Waln K. Brown Louis Winkler Friedrich Krebs Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/pafolklifemag Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, American Material Culture Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Cultural History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Folklore Commons, Genealogy Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, History of Religion Commons, Linguistics Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Feintuch, Burt; Ellis, Susan J.; Brown, Waln K.; Winkler, Louis; and Krebs, Friedrich, "Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 22, No. 3" (1973). Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine. 53. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/pafolklifemag/53 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contributors to this Issue B RT FEI T H , Philadelphia, Penn ylvania. currentl a doctoral tudent in Folklore and Folklife at the niver ity of Penn I ania. H e i a graduate of the Penn ylvania tate niver ity, wher h tudied und r Profe or amuel P. Bayard dean of Penn- ylvania' folklori t . J J. ELLI , Philadelphia, Penn ylvania, pre ent here her M .A. -

Wise Traditions for Wisetraditions Non Profi T Org

THE WESTON A. PRICE FOUNDATION® NUTRIENT-DENSE FOODS TRADITIONAL FATS LACTO-FERMENTATION BROTH IS BEAUTIFUL Wise Traditions for WiseTraditions Non Profi t Org. IN FOOD, FARMING AND THE HEALING ARTS U.S. Postage $10 Education Research Activism PAID SOY ALERT! TRUTH IN LABELING NON-TOXIC FARMING PREPARED PARENTING NURT PARENTING PREPARED FARMING NON-TOXIC LABELING IN TRUTH ALERT! SOY #106-380 4200 WISCONSIN AVENUE, NW Suburban, MD WASHINGTON, DC 20016 Permit 4889 URE Wise TTraditionsraditions IN FOOD, FARMING AND THE HEALING ARTS Volume 10 Number 1 Spring 2009 Spring 2009 10 Number 1 Volume THE WESTON A. PRICE FOUNDATION® for WiseTraditions IN FOOD, FARMING AND THE HEALING ARTS Education Research Activism NUTRIENT DENSE FOODS TRADITIONAL FATS LACTO-FERMENTATION BROTH IS BEAUTIFUL A CAMPAIGN FOR REAL MILK TRUTH IN LABELING PREPARED PARENTING SOY ALERT! LIFE-GIVING WATER The Cod Liver Oil Debate Cod Liver Oil Manufacture Reply to Dr. Joe Mercola on Cod Liver Oil NON-TOXIC FARMING PASTURE-FED LIVESTOCK NURTURING THERAPIES The Good Scot Diet Curds and Whey THERAPIES URING COMMUNITY SUPPORTED AGRICULTURE A PUBLICATION OF THE WESTON A. PRICE FOUNDATION® You teach, you teach, you teach! Education Research Activism Last words of Dr. Weston A. Price, June 23, 1948 COMMUNITY SUPPORTED AGRICULT LIFE-GIVING LIVESTOCK WATER FOR REAL MILK PASTURE-FED A CAMPAIGN Printed on Recycled Offset TECHNOLOGY AS SERVANT SCIENCE AS COUNSELOR KNOWLEDGE AS GUIDE Printed with soy ink - an appropriate use of soy WiseTraditions THE WESTON A. PRICE Upcoming Events IN FOOD, FARMING AND THE HEALING ARTS ® Volume 10 Number 1 FOUNDATION Spring 2009 Education Research Activism 2009 Apr 3-5 Long Beach, CA: Health Freedom Expo at the Long Beach Convention Center. -

LIBRETTO ♫ January, 2018 Symphony Village’S Newsletter Vol

Photo by George Drake LIBRETTO ♫ January, 2018 Symphony Village’s Newsletter Vol. XIII No. 1 DOWN MEMORY LANE EDITION! MISSION STATEMENT: Enhance the quality of life and promote a harmonious community through the timely publication of accurate information about residents, events, and activities in and around Symphony Village. HOA & GOVERNANCE, AND LOCAL CONTACTS Camilla Gaines, General Manager: [email protected] Rebecca Cook, Assistant General Manager: [email protected] Board of Directors Group Email: [email protected] Clubhouse Telephone: 410-758-8500 Clubhouse Address: 100 Symphony Way (not 138 Symphony Way) Bulk Pickup and Yard Waste: 410-758-1180 Trash Removal & Recycling: 410-742-0099 COMMITTEE REPORTS Expansion Update After the severe cold of early January, we finally broke ground on our expansion project on January 11. Be sure to check our Expansion Project web page for progress reports in the headline paragraph and photo coverage by George Drake. Also, please schedule any events with Rebecca, who is now maintaining the Master Calendar so that it can be coordinated with 1 construction activities. In general, committee meetings will be held in the Card Room using new 5’ round tables while the card tables are temporarily stored. The January 12 Board Meeting was the last scheduled Concert Hall event. Also, keep in mind that a good portion of the parking lot in front of the tennis court is closed for you and your car’s safety. This lot is being used by our contractor and may have large equipment or on-going construction activities. The tennis courts remain open. Look for the icon on the Home Page or Dashboard to access the Expansion Project webpage. -

Rhyming Dictionary

Merriam-Webster's Rhyming Dictionary Merriam-Webster, Incorporated Springfield, Massachusetts A GENUINE MERRIAM-WEBSTER The name Webster alone is no guarantee of excellence. It is used by a number of publishers and may serve mainly to mislead an unwary buyer. Merriam-Webster™ is the name you should look for when you consider the purchase of dictionaries or other fine reference books. It carries the reputation of a company that has been publishing since 1831 and is your assurance of quality and authority. Copyright © 2002 by Merriam-Webster, Incorporated Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Merriam-Webster's rhyming dictionary, p. cm. ISBN 0-87779-632-7 1. English language-Rhyme-Dictionaries. I. Title: Rhyming dictionary. II. Merriam-Webster, Inc. PE1519 .M47 2002 423'.l-dc21 2001052192 All rights reserved. No part of this book covered by the copyrights hereon may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission of the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America 234RRD/H05040302 Explanatory Notes MERRIAM-WEBSTER's RHYMING DICTIONARY is a listing of words grouped according to the way they rhyme. The words are drawn from Merriam- Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. Though many uncommon words can be found here, many highly technical or obscure words have been omitted, as have words whose only meanings are vulgar or offensive. Rhyming sound Words in this book are gathered into entries on the basis of their rhyming sound. The rhyming sound is the last part of the word, from the vowel sound in the last stressed syllable to the end of the word. -

Cultural Icons

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UK_topics#Cultural_icons Cultural icons Bagpipes Bagpipes are a class of musical instrument, aerophones using enclosed reeds. The term is equally correct in the singular or plural, although pipers most commonly talk of "pipes" and "the bagpipe". Skirl is a term used by pipers to describe an unintended shrill sound made by the chanter, and is usually produced when the chanter reed is too easy and thus the chanter is overblown. Sometimes the term is also somewhat mistakenly used to describe the general sound produced by a bagpipe. The history of the bagpipe is very unclear. However, it seems likely they were first invented in pre-Christian times. Nero is generally accepted to have been a player; there are Greek depictions of pipers, and the Roman legions are thought to have marched to bagpipes. The idea of taking a leather bag and combining it with a chanter and inflation device seems to have originated with various ethnic groups in the Roman empire. In the modern era the use of bagpipes has become a common tradition for military funerals and memorials in the anglophone world, and they are often used at the funerals of high-ranking civilian public officials as well. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UK_topics#Cultural_icons Big Ben Big Ben is the colloquial name of the Clock Tower of the Palace of Westminster in London and an informal name for the Great Bell of Westminster, part of the Great Clock of Westminster. The clock tower is located at the northwestern end of the building, the home of the Houses of Parliament, and contains the famous striking clock and bell. -

Bearscookbook.Pdf

Jack & Steve’s He-Man Adventure Cookbook, also known as THE BEARS’ COOKBOOK By Steve Freitag and Jack Garceau “Yum-o! Delish!” -- Rachael Ray, cookbook author and Food Network host “Charming … best of the bear cookbooks.” -- American Bear magazine (paraphrased) NOTE: This .pdf version is minus certain pages (mostly photo pages). ______________GAR-TAG PUBLISHING GROUP______________ COHOES MURFREESBORO SAN FRANCISCO The Bears' Cookbook A collection of recipes by Steve Freitag and Jack Garceau Entire contents of this book are (c) 1999 Steve Freitag and Jack Garceau. All rights are fully reserved. Individual recipes, where the source is cited, are copyrighted by their respective authors. .pdf version, February 2007 This book is dedicated to YOU whose exquisite taste in food and friends is beyond reproach ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Without the help and support of these people (among many others), this book would not be possible: Adam and Julia Philips, Amy Schoch, Andrea and Keith Stewart, Annalie Gonzales, Bert and Barbara Baker, Bert and Joanne Szoghy, Betty Tong and Paul Dunham, Bill Wasicsko, Billie Sue Freitag, Billy Garceau, Carl and Joyce Freitag, Carlos and Ari, Carolyn Arber, Cathy Kernaghan, Charlotte Druschel, Chris Brisel and Sandra, Chris Cavett, Chris Companik, Chuck Hester and Chris McC., Chuck Waseleski, Cliff Bemis, Cliff Meyer, Dave and Joe Shore, Dave Friedman, Dave Hersh, Dave Remele and Dave Slater, David and Andrea Freitag, Dees and Yuriko Stribling, Diane Deacon, Dirk Tarro, Doris Brown, Douglas Graves, Duc Nguyen, Ed B., Ed Caruso, -

Scrapple Is Typically Eaten As a Breakfast Side Dish

Scrapple Is Typically Eaten As A Breakfast Side Dish National Scrapple Day is observed annually on November 9th. Scrapple is arguably the first pork food invented in America. For those who are not familiar with scrapple, which is also known by the Pennsylvania Dutch name “pon haus,“ it is traditionally a mush of pork scraps and trimmings combined with cornmeal, wheat flour and spices. (The spices may include but are not limited to sage, thyme, savory and black pepper.) The mush is then formed into a semi-solid loaf, sliced and pan-fried. The immediate ancestor of scrapple was the Low German dish called panhas, which was adapted to make use of locally available ingredients and, in parts of Pennsylvania, it is still called Pannhaas, panhoss, ponhoss or pannhas. It was in the 17th and 18th centuries that the first recipes for scrapple were created by Dutch colonists who settled near Philadelphia and Chester County, Pennsylvania. Hence the origin of its discovery, it is strongly associated with rural areas surrounding Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington D.C., eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, eastern Virginia and the Delmarva Peninsula. Scrapple can be found in supermarkets throughout the area in both refrigerated and frozen cases. Home recipes for beef, chicken and turkey scrapple are available. Scrapple is sometimes deep-fried or broiled instead of pan frying. Scrapple is typically eaten as a breakfast side dish. There’s a very popular scrapple festival. Yes, you read that correctly. Now in its 25th year, the Apple Scrapple festival in Bridgeville, Del. — a short two-hour jaunt from Philly — celebrates all things scrapple and apples and attracts more than 25,000 visitors each year. -

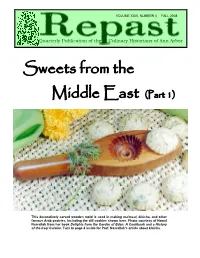

Sweets from the Middle East (Part 1)

VOLUMEVOLUME XVI, XXIV, NUMBER NUMBER 4 4 FALL FALL 2000 2008 Quarterly Publication of the Culinary Historians of Ann Arbor Sweets from the Middle East (Part 1) This decoratively carved wooden mold is used in making ma'moul, kleicha, and other famous Arab pastries, including the dill cookies shown here. Photo courtesy of Nawal Nasrallah from her book Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine. Turn to page 4 inside for Prof. Nasrallah’s article about kleicha. REPAST VOLUME XXIV, NUMBER 4 FALL 2008 Editor’s Note on Baklava Second Helpings Allowed! Charles Perry, who wrote the article “Damascus Cuisine” in our last issue, was the editor of a book Medieval Arab Cookery (Prospect Books, 2001) that sheds further light on the origins of baklava, the Turkish sweet discussed by Sheilah Kaufman in this issue. A dish described in a 13th-Century Baghdad cookery Sweets from the manuscript appears to be an early version of baklava, consisting of thin sheets of bread rolled around a marzipan-like filling of almond, sugar, and rosewater (pp. 84-5). The name given to this Middle East, Part 2 sweet was lauzinaj, from an Aramaic root for “almond”. Perry argues (p. 210) that this word gave birth to our term lozenge, the diamond shape in which later versions of baklava were often Scheduled for our Winter 2009 issue— sliced, even up to today. Interestingly, in modern Turkish the word baklava itself is used to refer to this geometrical shape. • Joan Peterson, “Halvah in Ottoman Turkey” Further information about the Baklava Procession mentioned • Tim Mackintosh-Smith, “A Note on the by Sheilah can be found in an article by Syed Tanvir Wasti, Evolution of Hindustani Sweetmeats” “The Ottoman Ceremony of the Royal Purse”, Middle Eastern Studies 41:2 (March 2005), pp.