Approximately 40% of a Live Beef Animal Weight Is Processed Through a Rendering Plant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Nobles, Currey Allen

ABSTRACT NOBLES, CURREY ALLEN. Processing Factors Affecting Commercially Produced Pork Bacon. (Under the direction of Dana J. Hanson.) Three studies were performed to assess the effects of processing and ingredient parameters on the production yields and consumer acceptance of pork bacon. Products were produced at a commercial processing facility and processed under standard plant procedures. Study 1 was conducted to assess the effect of sodium phosphate reduction on processing yields and consumer sensory perception of bacon. Standard sodium phosphate level bacon (SP) and low sodium phosphate level bacon (LP) were produced at a commercial bacon processing facility. The SP bacon was formulated to 0.05% sodium phosphate in the finished product. LP bacon was formulated to 0.005% sodium phosphate in the finished product. SP bacon trees (N=9; 575 individual pork bellies) and LP bacon trees (N=9; 575 individual pork bellies) were produced. Phosphate reduction had no effect (p>0.05) on smokehouse and cooler yields. Phosphate reduction also showed no effect (p>0.05) on yield of #1 and #2 bacon slices. At 30 days post processing consumers rated LP bacon higher than SP bacon (p<0.05) in the attribute of overall liking, but there was no clear preference (p>0.05) of either product among consumers. At 110 days post processing SP bacon was rated higher by consumers (p<0.05) than LP bacon in the attribute of overall flavor liking, but there was no clear preference (p>0.05) for either product. Sodium phosphate reduction was not detrimental to processing yields and still produced a product that was well received by consumers. -

Pressure Canner and Cooker

Pressure Canner and Cooker Estas instrucciones también están disponibles en español. Para obtener una copia impresa: • Descargue en formato PDF en www.GoPresto.com/espanol. • Envíe un correo electrónico a [email protected]. • Llame al 1-800-877-0441, oprima 2 y deje un mensaje. For more canning information and recipes, visit www.GoPresto.com/recipes/canning Instructions and Recipes ©2019 National Presto Industries, Inc. Form 72-719J TABLE OF CONTENTS Important Safeguards.............................Below How to Can Foods Using Boiling Water Method .......... 21 Getting Acquainted .................................. 2 How to Pressure Cook Foods in Your Pressure Canner ....... 24 Before Using the Canner for the First Time................ 3 Important Safety Information ......................... 24 Canning Basics...................................... 4 Helpful Hints for Pressure Cooking..................... 25 How to Pressure Can Foods............................ 5 Pressure Cooking Meat .............................. 26 Troubleshooting ..................................... 7 Pressure Cooking Poultry ............................ 29 Care and Maintenance ................................ 7 Pressure Cooking Dry Beans and Peas .................. 30 Canning Fruits ...................................... 9 Pressure Cooking Soups and Stocks .................... 31 Canning Tomatoes and Tomato Products................. 12 Pressure Cooking Desserts............................ 32 Pressure Canning Vegetables .......................... 15 Recipe Index ..................................... -

BATCH COOKER Product Brochure BATCH COOKER

BATCH COOKER Product brochure BATCH COOKER The Haarslev Batch Cooker is a straightforward, quick- to-install unit that you can bring on line quickly for the cooking, pressure cooking, hydrolysis or drying of an exceptional range of animal and poultry by-products. These include mixed meat offal and bones, poultry offal and wet feathers. It can operate at the 133°C temperatures important for sterilization, and is ideal for smaller-batch processing of particularly large particles (up to 50mm) – which helps BATCH COOKER SETUP FOR PRESSURE COOKING, cut back on pre-cooking crushing requirements. HYDROLYSIS OR DRYING A WIDE RANGE OF ANIMAL AND POULTRY BY-PRODUCTS. Furthermore, this solidly engineered, well-proven cooker can operate under pressures of up to 5 bar, ensuring your Making sure there is no water left in the input processing setup complies with the 2009/2011 EU Animal material is crucial prior to fat separation. This makes By-products Directive and can even process inputs an effective cooker vital for any batch-based dry containing hair, wool or feathers, for use in pet food. rendering process to operate profitably. BENEFITS APPLICABLE FOR: • Simple, rugged equipment for effective cooking • As part of high-temperature dry rendering lines in and drying in batches – pressurized if required meat or poultry processing plants • Very versatile – ideal for heating and drying a wide • Poultry rendering operations involving hydrolysis range of animal and poultry by-products of the feathers • Delivered pre-configured with all necessary valves, -

Snacks- -Starters

-Snacks- -Chilli Marinated Olives with Roasted Garlic and Crostini $8- House Pickled Egg $2- Pickled in whisky and spices -Haggis Fritters $9- fried Macsween’s haggis with homemade gravy Vegan Haggis Fritters $9– fried vegan Macsweens haggis with curry sauce House Pork Sausage Rolls $9– our hand rolled pork rolls with homemade gravy -Scotch Egg $9– wrapped in pork, rosemary, thyme and fennel with house gravy Curry Sauce and Chips $9- hand cut chips with our own Glasgow curry sauce Scottish Haggis Poutine $15- our hand cut chips, curds, house gravy and Macsween’s Haggis (veg or lamb) Quebecois Poutine $12- our hand cut chips, curds and house gravy -Starters- -Roasted Heirloom Beet Salad $14- with goat’s cheese, cherry tomatoes, baby spinach and whisky vinaigrette (add cold smoked salmon $6) -Ardbeg Whisky House Smoked Salmon Plate $17- pickled onion, capers, crostini and Mascarpone with Ardbeg whisky atomizer -Organic Baby Spinach, Watermelon Radish and Tomato Salad- Starter $8/Main $14- (Add Cold Smoked Salmon $6) -Aberdeenshire Finnan Haddie Cakes $14- panko fried North Sea Haddock with potato, red onion, caper and dill with chipotle aioli -Taste of Scotland Sharing Platter $19- scotch egg/haggis fritters/sausage rolls -Mains- -Fish and Chips $19- traditional Scottish fish supper with North Sea haddock in our own beer batter -Baked Mac and Cheese $17- aged cheddar, stilton and chevre with roasted garlic and cherry tomatoes (add bacon $2, add smoked salmon $6) -Scottish Steak Pie $18- hand cut top sirloin with stout and root veg under -

USING BOILING WATER-BATH CANNERS Kathleen Riggs, Family and Consumer Sciences Iron County Office 585 N

USING BOILING WATER-BATH CANNERS Kathleen Riggs, Family and Consumer Sciences Iron County Office 585 N. Main St. #5 Cedar City, UT 84720 FN/Canning/FS-02 December 1998 (or salt) to offset acid taste, if desired. This does not WHY CHOOSE BOILING WATER-BATH effect the acidity of the tomatoes. CANNING TO PRESERVE FOOD? BECOMING FAMILIAR WITH THE Boiling water-bath canning is a safe and economical method of preserving high acid foods. It has been used for PARTS OF A BOILING WATER-BATH decades—especially by home gardeners and others CANNER (See Illustration) interested in providing food storage for their families where quality control of the food is in ones’ own hands. These canners are made of aluminum or porcelain- Home food preservation also promotes a sense of personal covered steel. They have removable perforated racks or satisfaction and accomplishment. Further, the guesswork wire baskets and fitted lids. The canner must be deep is taken out of providing a safe food supply which has enough so that at least 1 inch of briskly boiling water will been preserved at home when guidelines for operating a be over the tops of jars during processing. water-bath canner are followed exactly, scientifically tested/approved recipes are utilized (1988 or later), and Some boiling-water canners do not have flat bottoms. A good quality equipment, supplies and produce are used. flat bottom must be used on an electric range. Either a flat or ridged bottom can be used on a gas burner. To WHAT FOODS ARE TYPICALLY ensure uniform processing of all jars with an electric PROCESSED USING THE BOILING range, the canner should be no more than 4 inches wider in diameter than the element on which it is heated. -

Cured and Air Dried 1

Cured and Air Dried 1. Sobrasada Bellota Ibérico 2. Jamón Serrano 18 month 3. Mini Cooking Chorizo 4. Morcilla 5. Chorizo Ibérico Bellota Cure and simple Good meat, salt, smoke, time. The fundamentals of great curing are not complicated, so it’s extraordinary just how many different styles, flavours and textures can be found around the world. We’ve spent 20 years tracking down the very best in a cured meat odyssey that has seen us wander beneath holm oak trees in the Spanish dehesa, climb mountains in Italy and get hopelessly lost in the Scottish Highlands. The meaty treasures we’ve brought back range from hams and sausages to salamis and coppas, each with their own story to tell and unique flavours that are specific to a particular place. 1. An ancient art 4. The practice of preserving meat by drying, salting or smoking stretches back thousands of years and while the process has evolved, there has been a renaissance in traditional skills and techniques in recent years. Many of our artisan producers work in much the same way as their forefathers would have, creating truly authentic, exquisite flavours. If you would like to order from our range or want to know more about a product, please contact your Harvey & Brockless account manager or speak to our customer support team. 3. 2. 5. Smoked Air Dried Pork Loin Sliced 90g CA248 British Suffolk Salami, Brundish, Suffolk The latest edition to the Suffolk Salami range, cured and There’s been a cured meat revolution in the UK in recent years smoked on the farm it is a delicate finely textured meat that with a new generation of artisan producers developing air dried should be savoured as the focus of an antipasti board. -

Olive Oil Jars Left Behind By

live oil jars left behind by the ancient Greeks are testament to our centuries- old use of cooking oil. Along with salt and pepper, oil Oremains one of the most important and versatile tools in your kitchen. It keeps food from sticking to pans, adds flavor and moisture, and conducts the heat that turns a humble stick of potato into a glorious french fry. Like butter and other fats, cooking oil also acts as a powerful solvent, unleashing fat-soluble nutrients and flavor compounds in everything from tomatoes and onions to spices and herbs. It’s why so many strike recipes begin with heating garlic in oil rather than, say, simmering it in water. The ancient Greeks didn’t tap many cooking oils. (Let’s see: olive oil, olive oil, or—ooh, this is exciting!—how about olive oil?) But you certainly can. From canola to safflower to grapeseed to walnut, each oil has its own unique flavor (or lack thereof), aroma, and optimal cooking temperature. Choosing the right kind for the task at hand can save you money, boost your health, and improve your cooking. OK, so you probably don’t stop to consider your cooking oil very often. But there’s a surprising amount to learn about What’s this? this liquid gold. BY VIRGINIAWILLIS Pumpkin seed oil suspended in corn oil—it looks like a homemade Lava Lamp! 84 allrecipes.com PHOTOS BY KATE SEARS WHERE TO store CANOLA OIL GRAPESEED OIL are more likely to exhibit the characteristic YOUR OIL flavor and aroma of their base nut or seed. -

Mincemeat Pie with Meat

MINCEMEAT PIE WITH MEAT Rather than write out a specific mincemeat recipe, I decided to make a comparison of how the proportions of ingredients changed over time. Now you can make your own! Some of them did specify quantity of spices; I’ve left that out due to space issues. N.B.: Beeton and Galt have both mincemeat with and w/o meat recipes (I’m only looking at w/ meat here). The other question to ask is, “how big is your pie?” It seems the English like to make mince pies individual-size (for example, in Harry Potter Ron confesses to eating 3 or 4). Beeton seems to be making smaller ones like that. The others don’t seem to specify, although once you tried to make 20 pies from the JOC recipe you’d know which size, I’m guessing smallish. Other questions that occur to me are “how much does a tongue weigh?” and “are calves feet really fatty?” I will add that I have made the E.F. version before and tried to short the suet, since it seems like a lot of fat. Don’t. It needs it to hold together. Except for getting sweeter and adding more apples (although that’s difficult to judge since they all use different measurements,) it looks like the proportions and spicing stay fairly consistent. That’s really quite remarkable. COOKBOOKS Elinor Fettiplace, early 17c English Martha Washington, early to mid 17th century English, but being used in America in the 18th century Amelia Simmons, 18c American Isabella Beeton, mid 19c English Galt, late 19c Canadian Joy of Cooking, mid 20c American E.F. -

Sheep Based Cuisine Synthesis Report First Draft

CULTURE AND NATURE: THE EUROPEAN HERITAGE OF SHEEP FARMING AND PASTORAL LIFE RESEARCH THEME: SHEEP BASED CUISINE SYNTHESIS REPORT FIRST DRAFT By Zsolt Sári HUNGARIAN OPEN AIR MUSEUM January 2012 INTRODUCTION The history of sheep consume and sheep based cuisine in Europe. While hunger is a biologic drive, food and eating serve not only the purpose to meet physiological needs but they are more: a characteristic pillar of our culture. Food and nutrition have been broadly determined by environment and economy. At the same time they are bound to the culture and the psychological characteristics of particular ethnic groups. The idea of cuisine of every human society is largely ethnically charged and quite often this is one more sign of diversity between communities, ethnic groups and people. In ancient times sheep and shepherds were inextricably tied to the mythology and legends of the time. According to ancient Greek mythology Amaltheia was the she-goat nurse of the god Zeus who nourished him with her milk in a cave on Mount Ida in Crete. When the god reached maturity he created his thunder-shield (aigis) from her hide and the ‘horn of plenty’ (keras amaltheias or cornucopia) from her horn. Sheep breeding played an important role in ancient Greek economy as Homer and Hesiod testify in their writings. Indeed, during the Homeric age, meat was a staple food: lambs, goats, calves, giblets were charcoal grilled. In several Rhapsodies of Homer’s Odyssey, referring to events that took place circa 1180 BC, there is mention of roasting lamb on the spit. Homer called Ancient Thrace „the mother of sheep”. -

Our Product List Our Product List at a Glance at a Glance

385352 Product List v8_Layout 1 7/10/13 3:20 PM Page 1 385352 Product List v8_Layout 1 7/10/13 3:20 PM Page 1 OUR PRODUCT LIST OUR PRODUCT LIST AT A GLANCE AT A GLANCE FRESH CUT BEEF Pork Loin Chops BACON FRESH CUT BEEF Pork Loin Chops BACON Beef Tenderloin Thick Cut Pork Loin Chops *Hickory Smoked Bacon Beef Tenderloin Thick Cut Pork Loin Chops *Hickory Smoked Bacon Ribeye Steak Center Cut Pork Loin Chops *Pepper Bacon Ribeye Steak Center Cut Pork Loin Chops *Pepper Bacon Porterhouse Steak Boneless Pork Chops *Beef Bacon Porterhouse Steak Boneless Pork Chops *Beef Bacon Chuckeye Steak Pork Loin Back Ribs *Homestyle Cottage Bacon Chuckeye Steak Pork Loin Back Ribs *Homestyle Cottage Bacon T-Bone Steak Pork Liver *Thick Sliced Bacon T-Bone Steak Pork Liver *Thick Sliced Bacon New York Strip Steak Lard *Apple Cinnamon Bacon New York Strip Steak Lard *Apple Cinnamon Bacon Sirloin Steak Boneless Boston Butts *Raspberry Chipotle Bacon Sirloin Steak Boneless Boston Butts *Raspberry Chipotle Bacon Beef Brisket Fresh Bone-In Ham Roast *Honey Glazed Bacon Beef Brisket Fresh Bone-In Ham Roast *Honey Glazed Bacon Boneless Prime Rib Roast Country-Style Pork Ribs *Maple Bacon Boneless Prime Rib Roast Country-Style Pork Ribs *Maple Bacon Flank Steak *Pulled Pork w/Sauce Flank Steak *Pulled Pork w/Sauce Boneless Beef Roast *Stuffed Pork Chops SMOKED SAUSAGES Boneless Beef Roast *Stuffed Pork Chops SMOKED SAUSAGES Oxtail *Smoked Center Cut Chops **Grand Champion Bratwurst Oxtail *Smoked Center Cut Chops **Grand Champion Bratwurst Soup Bones Smokehouse -

Jirou Bao Zi

Jīròu Bāo Zǐ Fàn Chinese Clay Pot Rice with Chicken and Mushrooms Yield: Serves 2-4 Ingredients: Rice: 1 Cup Jasmine Rice (Tàiguó Xiāng Mǐ) - can substitute long grain white rice 1 Cup Chicken Stock (Jītāng) 1 Tbs Oil - can use vegetable, canola, or rapeseed oil ¼ tsp Kosher Salt (Yàn) Chicken and Marinade: 2 lbs Boneless/Skinless Chicken Thighs (Jītuǐ Ròu) - cut into bite sized pieces (apx ¼" strips) 1 Green Onion (Cōng) - minced ½ inch piece Fresh Ginger (Jiāng) - peeled and finely julienned 1 ½ Tbs Cornstarch (Yùmǐ Diànfěn) 1 Tbs Light Soy Sauce (Shēng Chōu) 1 Tbs Dark Soy Sauce (Lǎo Chōu) 2 tsp Oyster Sauce (Háoyóu) 1 tsp Shao Xing Rice Wine (Liàojiǔ) 1 tsp Toasted Sesame Oil (Zhīmayóu) ½ tsp Granulated Sugar (Táng) ⅛ tsp Ground White Pepper (Bái Hújiāo) - or to taste 'Veggies and Garnish': 8-10 Dried Black Mushrooms [AKA Shiitake] (Xiānggū) 3 Tbs Dried Black Fungus [AKA Wood Ear OR Cloud Ear Mushroom] (Yún ěr) 6-8 Dried Lily Buds (Bǎihé Yá) 2 Green Onions (Cōng) - chopped -OPTIONAL- ½ lb Chinese Broccoli (Jiè Lán) - cut into 2 inch pieces Taz Doolittle www.TazCooks.com Jīròu Bāo Zǐ Fàn Chinese Clay Pot Rice with Chicken and Mushrooms Preparation: 1) Place your dried black fungus and dried lily buds in a small bowl and cover with water - Set aside for 15 minutes 2) Place your dried black mushrooms in a small bowl and cover with hot water - Set aside for 30 minutes 3) After 15 minutes, rinse the black fungus and lily buds with clean water - Trim off the woody stems from the lily buds and cut them in half - Return the black fungus and -

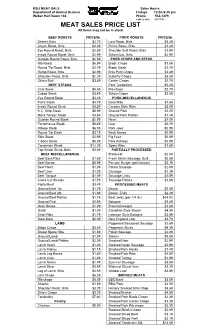

MEAT SALES PRICE LIST All Items May Not Be in Stock

KSU MEAT SALE Sales Hours: Department of Animal Science Fridays 12:00-5:45 pm Weber Hall Room 166 Phone 532-1279 expires date 05/31/05 MEAT SALES PRICE LIST All items may not be in stock BEEF ROASTS PRICE/lb. PORK ROASTS PRICE/lb. Brisket, Bnls $2.79 Loin Roast, Bnls $3.49 Chuck Roast, Bnls $2.39 Picnic Roast, Bnls $1.49 Eye Round Roast, Bnls $2.89 Shoulder Butt Roast, Bnls $1.59 Inside Round Roast, Bnls $2.99 Sirloin Butt, Bnls $2.99 Outside Round Roast, Bnls $2.59 PORK CHOPS AND STEAK Rib Roast $8.99 Blade Chops $1.89 Round Tip Roast, Bnls $2.79 Blade Steak $1.79 Rump Roast, Bnls $2.99 Bnls Pork Chops $3.69 Shoulder Roast, Bnls $2.29 Butterfly Chops $3.69 Sirloin Butt $3.89 Center Chops $2.79 BEEF STEAKS Pork Tenderloin $5.29 Club Steak $5.69 Rib chops $2.79 Cubed Steak $3.49 Sirloin Chops $2.09 Eye Round Steak $3.49 PORK-MISCELLANEOUS Flank Steak $4.79 Back Ribs $1.69 Inside Round Steak $3.29 Country Style Ribs $2.09 K.C. Strip Steak $6.69 Ground Pork $1.29 Mock Tender Steak $3.69 Ground Pork Patties $1.49 Outside Round Steak $2.99 Heart $1.09 Porterhouse Steak $6.49 Liver $0.79 Ribeye Steak $6.59 Pork Jowl $0.99 Round Tip Steak $3.19 Neck Bones $0.99 Skirt Steak $2.99 Pig Feet $0.89 T-bone Steak $6.39 Pork Kidneys $0.99 Tenderloin Steak $12.29 Spare Ribs $1.89 Top Sirloin Steak, Bnls $3.89 PARTIALLY PROCESSED BEEF-MISCELLANEOUS Bratwurst $2.69 Beef Back Ribs $1.69 Fresh Italian Sausage, Bulk $2.89 Beef Bones $0.99 Por-con Burger (pork-bacon) $2.19 Beef Heart $1.09 Potato Sausage $2.69 Beef Liver $1.09 Sausage $1.39 Beef Tongue $1.69