Containerized Grain Supply Chain in Western Canada: Opportunities and Regulatory Barriers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Plastic Resin Export Supply Chain

Moving Texas Exports Examining the role of transportation in the plastic resin export supply chain TRANSPORTATION Policy Research CENTER TRANSPORTATION Policy Research CENTER CONTENTS Introduction .......................................................................................................1 Background .................................................................................................................2 Plastic Resin Export Supply Chain .................................................................4 Transportation Issues .......................................................................................7 Captive Rail...................................................................................................................8 Rail Capacity ................................................................................................................8 Truck Driver Shortages ............................................................................................8 Overweight Regulations .........................................................................................8 Heavy-Weight Corridors ........................................................................................10 Last-Mile Congestion .............................................................................................10 Port Gate Congestion and Port Gate Hours ...................................................11 Container Availability ............................................................................................11 -

N.Y. C. Oval System Evolution and Applications

NEW YORK THE NEW YORK (ENTR-AL CENTRAL LINES N.Y. C. OVAL SYSTEM EVOLUTION AND APPLICATIONS PART ONE BY H. L. VAIL JR. N.Y. C. S- 337400 Container Car, Lot C- 100, 18" x 9" Oval, Red car with Red container s . The New York Central Oval, reportedly suggested by an cars, the background of the "Oval" was painted black. On employee in about 1904, underwent. a seri el of minor container cars, Lot C.l 01 and C-1 OZ the cars were painted changes during ita .use until the major design in 1958 black, the containers were red, except for refrigerated when the col or-: one was designed for use on the "New" jacle containers, which were whit e. green cars. This article covers the period up to thi e Z) Flat Cars, and Speei al Flat Cars with higher side sills change. The original herald had Roman capital letters used the lZ" high oval. All cars were painted black. and was designed in five sizes for the "New York Central Lines"andusedas follows on revenue service cars. It 3) All "Self Clearing" Hopper care, Gondola cars and Hop was, of course, used on other equipment, bridges, and per Bottom Gondola cars painted black. Double Deck as the of fi cial company 1 ogo. Stock cars painted red, with the background of the oval NYC Lines Super- painted black. The Double Deck Stock cars had the panel Dwg. No. Oval * Used On seded Date on which· the herald was painted mounted on the upper part &: Date Size By of the car side just below the eaves. -

The Impact of Jumbo Covered Hopper Cars on Kansas Shortline Railroads

Report No. K-TRAN: KSU-04-3 FINAL REPORT THE IMPACT OF JUMBO COVERED HOPPER CARS ON KANSAS SHORTLINE RAILROADS Michael W. Babcock James Sanderson Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas SEPTEMBER 2004 K-TRAN A COOPERATIVE TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH PROGRAM BETWEEN: KANSAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS 1 Report No. 2 Government Accession No. 3 Recipient Catalog No. K-TRAN: KSU-04-3 4 Title and Subtitle 5 Report Date THE IMPACT OF JUMBO COVERED HOPPER CARS ON KANSAS September 2004 SHORTLINE RAILROADS 6 Performing Organization Code 7 Author(s) 8 Performing Organization Report Michael W. Babcock and James Sanderson No. 9 Performing Organization Name and Address 10 Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Kansas State University Department of Economics; 317 Waters Hall 11 Contract or Grant No. Manhattan, Kansas 66506-4001 C1401 12 Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13 Type of Report and Period Kansas Department of Transportation Covered Bureau of Materials and Research Final Report 700 SW Harrison Street June 2003 - July 2004 Topeka, Kansas 66603-3754 14 Sponsoring Agency Code RE-0338-01 15 Supplementary Notes For more information write to address in block 9. 16 Abstract Class I railroads have been replacing 263,000-pound (loaded weight) covered hopper cars capable of handling 100 tons of grain with 286,000-pound covered hopper cars that can handle 111 tons. While these heavier cars provide a decrease in railroad cost per ton-mile for the Class I (Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe) Railroads; they will cause a significant increase in operating and maintenance costs for the shortline railroads in the state of Kansas. -

Containerized Bulk Handling

Containerized Bulk Handling This section contains information on alternative systems for handling bulk commodities. Containerized Bulk Handling Fill Pit To Ship Solutions Containerized Bulk Handling Transport Containerized Bulk Handling Load Process Store www.ramspreaders.com www.cbhgroup.org www.pittoship.com ContainerizedContainerized Bulk Bulk Handling Handling Containerized Bulk Handling Process - Conventional Process Mine Processing Facility Land Transport Load commodity Land Transport Quay Side Wagon Tipper 50 Million USD Ship Loading Port Storage Sheded & ConveConveyorsyo With Revolver ® Load Ship Lift from Storage 80 Million 50 Million USD USD Containerized Bulk Handling ContainerizedRevolver ProductBulk Handling Range Equipment: Integrated Approach Equipment: Revolver® MHC Revolver® Cranes Dust Suppression Ship to Shore Mobile Harbour Reach Stacker Container Handlers Containers Ship Crane Special trailers ContainerizedContainerized Bulk Bulk Handling Handling ContainerizedContainerized Bulk Bulk Handling Handling Equipment: Containers Equipment: Dust Suppression Lid Lifted & Auto open Internal Lockable Reinforcement latch “ICE CUBE-interior design” Low hang up With tapered side walls and curved Rail & Corner casting gussets in corners if required Pit To Ship Solutions Containerized Bulk Handling Containerized Bulk Handling Equipment: Ancillary Consultants Important, WHY? • They recommend us in studies • They help us in implementation • They promote our solution • They Innovate Cranes Mobile Equipment Revolver Specific Trailer Containerized Bulk Handling Containerized Bulk Handling Environment Why we are green # Tips at bottom of hatch so less dust Conventional Operations # Less dust than ship loader as it doesn’t displace as much air # No open stock piles # No clean down of ship loader between commodities In many cases, new projects won’t be approved without the lower environmental impact Containerized Bulk Handling ContainerizedContainerized Bulk Bulk Handling Handling Rotary unloading virtually no dust generated. -

Freight Services the Alaska Railroad (ARRC) Provides Seam- ARM Barge Move from Whittier to Anchorage Or Less Freight Operation Between Shipping Points in Fairbanks

Freight Services The Alaska Railroad (ARRC) provides seam- ARM barge move from Whittier to Anchorage or less freight operation between shipping points in Fairbanks. Barges also move railcar shipments the Lower 48 to many destinations in Alaska. Port to/from Alaska via Prince Rupert, interchanging facilities in Seattle, Whittier, Seward and Anchor- with Canadian National Railway (CN). The CN age provide crucial links between marine and land barge was discontinued in early spring 2021. transportation modes. Rail yards in Seward, Whit- tier, Anchorage and Fairbanks offer centralized • Trailers/Containers on Flat Cars — TOFC/ distribution hubs for other transportation modes. COFC moves north and south between Seward, Whittier, Anchorage and Fairbanks. Freight Revenue & Expense • Coal — Coal from Usibelli Coal Mine in Healy Freight is the Alaska Railroad’s bread-and- moves to the Fairbanks area for local markets. butter, typically generating more than half of operating revenues (excluding capital grants). In • Gravel — Seasonally (April – October) aggregate 2019, a more typical year, the railroad hauled 3.49 products move from the Matanuska-Susitna million tons of freight, generating 56% of operating Valley to Anchorage. revenues. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic dev- • Miscellaneous/In-state Local — Other freight astated ARRC’s passenger business and lowered includes specialty movements of very large or freight demand. As a result, ARRC hauled 2.8 mil- lion tons of freight, generating three-fourths (76%) oddly-shaped equipment and materials, as well of operating revenues. as in-state shipments of cement, scrap metal, Major lines of freight business include: military equipment and pipe. • Petroleum — Most petroleum products have While freight-hauling is a major revenue source, it also involves capital- and maintenance- moved from Anchorage to a fuel distribution intensive expense. -

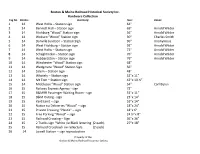

Station Sign 64” 2 14 Bennet

Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Inc. Hardware Collection Tag No. File No: Inventory: Size: Donor: 1 14 West Hollis – Station sign 64” 2 14 Bennett Hall – Station sign 69” Arnold Wilder 3 14 Fitchburg “Wood” Station sign 56” Arnold Wilder 4 14 Woburn “Wood” Station sign 30” Charles Smith 5 14 Danville Junction – Station Sign 96” Anonymous 6 14 West Fitchburg – Station sign 92” Arnold Wilder 7 14 West Hollis – Station sign 72” Arnold Wilder 8 14 Scheghticoke – Station sign 76” Arnold Wilder 9 14 Hubbardston – Station sign 76” Arnold Wilder 10 14 Winchester “Wood” Station sign 68” 11 14 Wedgmere “Wood” Station Sign 56” 12 14 Salem – Station sign 48” 13 14 Whately – Station sign 52”x 11” 14 14 Mt Tom – Station sign 42”x 10 ½” 15 14 Middlesex “Wood” Station sign 54” Carl Byron 16 15 Railway Express Agency - sign 72” 17 15 B&MRR Passenger Waiting Room - sign 32”x 11” 18 15 B&M Outing - sign 23”x 14” 19 15 Yard Limit – sign 16”x 14” 20 15 Notice no Deliveries “Wood” – sign 18”x 24” 21 15 Private Crossing “Plastic” – sign 18”x 6” 22 15 Free Parking “Wood” – sign 24 ½”x 8” 23 15 Railroad Crossing – Sign 36”x 36” 24 15 2 Tracks sign “White /w Black lettering (2 each) 27”x 18” 25 15 Railroad Crossbuck /w reflectors (2 each) 26 14 Lowell Station – sign reproduction Property of the Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Inc. Hardware Collection Tag No. File No: Inventory: Size: Donor: 27 15 Hand Held Stop – sign Donald S. -

October 2020

Volume 1, Issue 1 October 2020 In this issue: Welcome to the FEBT Newsletter 2 Fall Reunion Goes Virtual 2 Making Tracks at Robertsdale 3 FEBT Volunteers Continue Rockhill Restoration 6 In the Shops and Along the Line 8 Editorial - Introducing Your Editor 11 FEBT Track Crew poses in front of the Robertsdale station on September 18th. - Craig A. Musser photo 1 WELCOME TO THE NEWSLETTER Welcome to the new FEBT Newsletter! I hope you find it interesting and informative and with time, each issue highly anticipated. Each month the Newsletter will provide you with the latest news, restoration progress, volunteer and resource needs, and insight into upcoming events. These are exciting times on the EBT and we owe it to you, our dedicated members and supporters, to keep you informed and up to date. I very much appreciate that Doug Davenport of La Plata, MD has stepped forward to be our Newsletter Editor. He, like me, has had ties to the EBT since very early childhood. Lee Rainey is also to be commended for his efforts in getting the Newsletter off the ground. Without either of them the Newsletter would have forever been "the next priority" rather than the reality. Thank you Doug and Lee! Andy Van Scyoc President FALL REUNION GOES VIRTUAL In the interest of keeping you and your loved ones safe and healthy, FEBT is taking the 2020 Fall Reunion virtual. Along with the annual business meeting the virtual event will include speakers - Henry Posner, Chairman of the EBT Foundation - Dave Domitrovich, Chief Mechanical Officer of the EBT Foundation - Ron Pearson, "Searching for the Lost Robertsdale Coal Mines and Coal Cleaning Plant" MEMBERSHIP BOX SCORE The Friends of the East Broad Top is up to 1318 active members The event is FREE, but registration is required. -

The Vibration Impact of Heavy Freight Train on the Roadbed

Procedia Engineering Volume 143, 2016, Pages 1136–1143 Advances in Transportation Geotechnics 3 . The 3rd International Conference on Transportation Geotechnics (ICTG 2016) The Vibration Impact of Heavy Freight Train on The Roadbed Andrei Petriaev The Petersburg State Transport University (PSTU), St.Petersburg, Russia [email protected] Abstract In this paper presents field studies of vibrodynamic impacts from passing heavy trains on the roadbed. The movement of railway rolling stock cause oscillations of the track superstructure, which manifest themselves in the form of noise and vibration. The increase in loads and speeds of trains leads to a significant increase dynamic vibration effects on the roadbed. As a result of this exposure the intensity of the accumulation of uneven residual deformation of the railway track increases, that affects not only on the roadbed, but also on constructions of buildings and construction. Keywords: heavy trains, roadbed, vibrodynamic impact, the attenuation of the amplitudes of the oscillations. 1 Introduction The Increasing the carrying capacity of the railways should be decided by the intensification of the existing rail network. Firstly, it is planned to increase the weight of trains by increasing the linear load on the track and increase the length of trains. For these purposes the railways acquire heavy-duty eight-axle wagons with axle load up to 250 kN and powerful locomotives with loads up to 270-300 kN/axle. In recent years, the construction of rolling stock and track superstructure have undergone substantial changes, which, of course, reflected in the subgrade. At the same time, constructive solutions roadbed remains essentially unchanged, but its operational state, in some cases, characterized by a decrease of the elastic properties and bearing capacity. -

Pullman Company Archives

PULLMAN COMPANY ARCHIVES THE NEWBERRY LIBRARY Guide to the Pullman Company Archives by Martha T. Briggs and Cynthia H. Peters Funded in Part by a Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Chicago The Newberry Library 1995 ISBN 0-911028-55-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................. v - xii ... Access Statement ............................................ xiii Record Group Structure ..................................... xiv-xx Record Group No . 01 President .............................................. 1 - 42 Subgroup No . 01 Office of the President ...................... 2 - 34 Subgroup No . 02 Office of the Vice President .................. 35 - 39 Subgroup No . 03 Personal Papers ......................... 40 - 42 Record Group No . 02 Secretary and Treasurer ........................................ 43 - 153 Subgroup No . 01 Office of the Secretary and Treasurer ............ 44 - 151 Subgroup No . 02 Personal Papers ........................... 152 - 153 Record Group No . 03 Office of Finance and Accounts .................................. 155 - 197 Subgroup No . 01 Vice President and Comptroller . 156 - 158 Subgroup No. 02 General Auditor ............................ 159 - 191 Subgroup No . 03 Auditor of Disbursements ........................ 192 Subgroup No . 04 Auditor of Receipts ......................... 193 - 197 Record Group No . 04 Law Department ........................................ 199 - 237 Subgroup No . 01 General Counsel .......................... 200 - 225 Subgroup No . 02 -

The Coupler People® $12.59

Kadee® Quality Products Co. 673 Avenue C White City, OR 97503-1078 U.S.A. Tel: 541-826-3883 FAX: 541-826-4013 http://www.kadee.com e-mail: [email protected] The Coupler People® August 2017 The Coupler People® Made & Assembled Entirely in the U.S.A. HO-Scale Hopper Coal Loads 6 per package Loads will fit most 2 bay hoppers on the market including Atlas, Athearn, MDC & Bowser hoppers. They can be easily modified to fit in other open hoppers. Load length is 32 1/2 scale feet. #171 Lump/Egg - (small) .......................................................... was $13.25 #172 Large Lump - (medium) ................................................... $12.59 #173 Mine Run - (large) ............................................................ Save 5% #171 #172 #173 Valid 8/8/17 through 9/11/17 online orders only. ©2017 Kadee ® Quality Products Co. Tel: 541-826-3883 FAX: 541-826-4013 www.kadee.com e-mail: [email protected] August 2017 New Rolling Stock! Kadee® prides itself in creating and manufacturing premium “RTR” rolling stock as close to scale & detail as possible. Model railroaders can expect only the best quality & craftsmanship with every Kadee® quality product. Nothing stacks up to the accuracy, detail, quality, & authenticity of Kadee® Cars over all other “RTR” cars on the market. 40’ PS-1 Boxcar 50’ PS-1 Boxcar PS-2 Hopper HO-Scale Ready-to-Run Rolling Stock SOLD OUT 8657 C&NW #4094 ...... $42.95 7062 RDG #81089 ....... $42.95 Lot: 8258 - Series: 4042-4141 Lot: BSC 121 - Series: 81000-81999 BLT. 1955 - Factory New BLT. 1948 - Factory New NEW Alkali Resisting Light Gray NEW Black FUTURE SCHEDULED CARS Limited Quantities Limited Quantities 2017 KDC Christmas Car. -

Chapter 14 Yards and Terminals1

CHAPTER 14 YARDS AND TERMINALS1 FOREWORD This chapter deals with the engineering and economic problems of location, design, construction and operation of yards and terminals used in railway service. Such problems are substantially the same whether railway's ownership and use is to be individual or joint. The location and arrangement of the yard or terminal as a whole should permit the most convenient and economical access to it of the tributary lines of railway, and the location, design and capacity of the several facilities or components within said yard or terminal should be such as to handle the tributary traffic expeditiously and economically and to serve the public and customer conveniently. In the design of new yards and terminals, the retention of existing railway routes and facilities may seem desirable from the standpoint of initial expenditure or first cost, but may prove to be extravagant from the standpoint of operating costs and efficiency. A true economic balance should be achieved, keeping in mind possible future trends and changes in traffic criteria, as to volume, intensity, direction and character. Although this chapter contemplates the establishment of entirely new facilities, the recommendations therein will apply equally in the rearrangement, modernization, enlargement or consolidation of existing yards and terminals and related facilities. Part 1, Generalities through Part 4, Specialized Freight Terminals include specific and detailed recommendations relative to the handling of freight, regardless of the type of commodity or merchandise, at the originating, intermediate and destination points. Part 5, Locomotive Facilities and Part 6, Passenger Facilities relate to locomotive and passenger facilities, respectively. -

Classic Freight Cars, Vol. 6: Loaded Flats and Gondolas by Henry Maywald

Classic Freight Cars, Vol. 6: Loaded Flats And Gondolas By Henry Maywald READ ONLINE If you are looking for a ebook by Henry Maywald Classic Freight Cars, Vol. 6: Loaded Flats and Gondolas in pdf form, then you have come on to the loyal website. We furnish the utter option of this book in txt, doc, DjVu, PDF, ePub forms. You may reading by Henry Maywald online Classic Freight Cars, Vol. 6: Loaded Flats and Gondolas either load. As well as, on our site you can read the instructions and different art eBooks online, either download their as well. We like attract attention that our site not store the eBook itself, but we give url to the website where you can load either read online. So if you need to download Classic Freight Cars, Vol. 6: Loaded Flats and Gondolas by Henry Maywald pdf, then you've come to the loyal site. We own Classic Freight Cars, Vol. 6: Loaded Flats and Gondolas DjVu, PDF, txt, doc, ePub forms. We will be happy if you come back to us afresh. Classic freight cars, volume 9 from karen's books Classic Freight Cars, Volume 9 - Includes insulated boxcars and mechanical reefers. Inlcudes over 170 color photos of insulated boxcars and mechanical refrigerator [PDF] How Anansi Learned Self-Esteem: 10 Original Stories For Building Self-Confidence And Self-Respect.pdf Consignment - vp Classic Metal Works; Clever Models; Con-Cor; Consignment Items; Deluxe Innovations; Depots by John; Design Preservation Models; Detail 160 Products; Digitrax [PDF] Early American Dolls In Full Color, The Creative Genius Of Unsophisticated America.pdf The history of the pennsylvania railroad for sale The History Of The Pennsylvania Railroad For Sale Locally :: DealLocal.com :: Everything You Need Cars Of Pacific Electric, Vol.